Different forms of the name “Habiru,” such as “Abiru,” “Apiru,” and “Hapiru,” all relate to the same group of people mentioned in ancient Near Eastern literature from the second millennium BC. The Habiru were precarious people who all found themselves on the outside of civilization. Numerous texts written between around 2000 and 1200 BC in Egyptian, Akkadian, Sumerian, and Ugaritic all make reference to them. Their existence is verified in Egypt, Mesopotamia, the Levant, and Syria.

Some writings label the Habiru as nomads, while others use terms like “semi-sedentary,” “marginalized,” “outlaw,” “rebel,” “mercenary,” “slave,” and “migrant worker.” The significance of this name, as well as any possible ties between the Habiru and the Hebrews of the Bible, have been argued about in academic circles. In the Bronze Age, the Habiru lived in the peripheries of several states, somewhat unlike the Hebrews (ʿibrîm). However, these concepts are not synonymous with one another.

Etymology of Habiru

The term “Habiru,” appearing around 250 times in ancient Near Eastern documents of the second millennium BC, is of Semitic origin but lacks a clear definition. In Akkadian texts, it is transcribed as ḫabiru/ḫapiru. Scholars debate its exact meaning, with two possible etymologies considered. One suggests it’s related to the root ḫbr (“to bind, unite”), indicating “the confederates,” or the toponym ḫbrn (Hebron), translating to “the Hebronites.” Another interpretation connects it to the Semitic root ʿbr (“to pass”), denoting refugees or fugitives. In some contexts, it’s linked to the term ˓pr (“dust, clay”), signifying socially inferior populations (“the dusty ones”). The Sumerian equivalent, SA.GAZ, refers to desert-dwelling bandits, indicating that “Habiru” might have been adopted to describe them due to their organization into mobile groups, city threats, and avoidance of central authority.

Who Were the Habiru?

Multiple 2nd-century BC sources mention the Habiru. They tend to cluster on the outskirts of major cities and states. Being an outsider to the places they visit is one of their defining features. They aren’t always tied together by shared history or homeland. In several historical accounts, they are depicted as violent and menacing, endangering the safety of many communities. To ensure their safety, several towns hired the Habiru to fight on their behalf as mercenaries.

The local leaders and military commanders had to deal with them. They have both fought against the Habiru and recruited them as auxiliary warriors. They worked for local lords in Babylonia, Alalakh, and Hattusa. Their relations are more tense in Mari and Egyptian writings. They banded together to launch raids against civilized areas.

The Amarna era provides the bulk of available information about these nomadic people. Habiru have been discovered in Egypt, where they have been held as slaves. They seem to be displaced people who were forced to leave their homes for different causes. They formed bands but never counted as a distinct group. When a new order was created in the Near East at the end of the second millennium, after the collapse of the previous Bronze Age, they disappeared from written records.

Historical References to the Habiru

Alishar: 19th century BC

The word “habiru” was first documented in a letter from ancient Alishar Hüyük, Anatolia. Assyrian commercial sites existed in the area as early as the Paleolithic era (19th century BC). Prisoners from the Assyrian palace are mentioned in the letter as the Habiru men (“awili habiri”). Possible ransom terms and conditions are laid forth. A person named Enna-Aššur writes a letter to Nabi-Enlil.

The question on Enna-Aššur’s mind was whether or not “the princess” was willing to let the males go. If they were held for ransom, he wanted Nabi-Enlil to pay it. He promised him that he would transfer the money without delay and stressed that he had no qualms about paying the desired sum. The fact that these Habiru males were connected to an Assyrian palace and had the financial means to pay any ransom attests to their high social rank. It’s possible that they were palace guards.

Paleo-Babylonian: 19th–17th century BC

The Larsa settlement, in southern Mesopotamia, recorded the presence of the Habiru during the reign of Rim-Sîn I, a ruler contemporary with Babylon’s Hammurabi. Equipment for Habiru troops came from the temple of Shamash’s (a deity) administration. Officers were outfitted with garments purchased with temple funds. The SA. GAZ is also mentioned in seven administrative papers from the time of Rim-Sîn I’s brother and predecessor, Warad-Sîn. These men received a few pets and chickens. After that, we don’t see any more Habiru in southern Mesopotamia.

Habiru is also referenced in texts from Upper Mesopotamia and Syria during the same time period. Mari documents dating from 1810 BC to 1700 BC include them often. The Harran area was the target of coordinated invasions and pillages by Habiru during Zimri-Lim’s rule. According to a letter, two hundred Habiru troops supported a Zimri-Lim opponent. In this setting, the Habiru seem to be a part of the local people, as stated by Mary P. Gray. A contrasting approach was suggested by J.-M. Durand, who labels them “troublemakers, often associated with mischief.” He suggests that the phrase, when read as hapirum, is related to the Semitic root PR, which means “to leave one’s home.” In this sense, it is a political exile for someone who has left their home because of a power conflict, as was typical at this time in Upper Mesopotamia.

A document written in Elamite Susa addresses the logistics of supplying Amorite troops stationed all throughout the country. The term “Habiru” is used to describe one of them.

Around 1600 BC, an eight-column Akkadian clay artifact called the Tikunani Prism recorded the names of 438 Habiru, the vast majority of whom had Hittite origins. Located in modern-day Turkey, near the city of Diyarbakir, they worked for King Tunib-Teshub of the Tikunani kingdom in Upper Mesopotamia. This kingdom was apparently friendly with the Hittite monarch Ḫattušili I and even served as his vassal, as shown by a letter. A tablet from the same canon has oracle prophecies about Habiru invasions.

Alalakh: 19th–15th century BC

An 18th-century BC year name in Alalakh (“the year when King Irkabtum […] made peace with the Habiru”) alludes to the existence of Habiru inside or near the kingdom of Yamhad (an ancient Semitic kingdom). Several manuscripts from the 15th century BC, when the city was a vassal of the Mitanni, mention the Habiru. According to the Alalakh texts, the Habiru were more complex than simple bandits. The inscription of Idrimi (the King of Alalakh) tells the fictionalized tale of his life. After being cast out of his country, the exiled prince of Aleppo sought sanctuary among the Habiru in Canaan.

Habiru, a fellow refugee from Aleppo, formed an army that he used to capture control in Alalakh. After some time, he was officially crowned king of Alalakh, becoming a vassal to the Mitanni and ushering in a new dynasty. The Habiru were now part of his main army. The Habiru now emerged as armed men under the leadership of his son and successor, Niqmepa. There were 1,436 men in all, and 80 of them possessed chariots.

These gentlemen were representatives of society’s elite. A priest of the Hittite goddess Ishara was among them. Other sources made reference to SA.GAZ troops serving the kingdom, some of whom had Hittite-sounding names.

Period of Nuzi: 15th–14th century BC

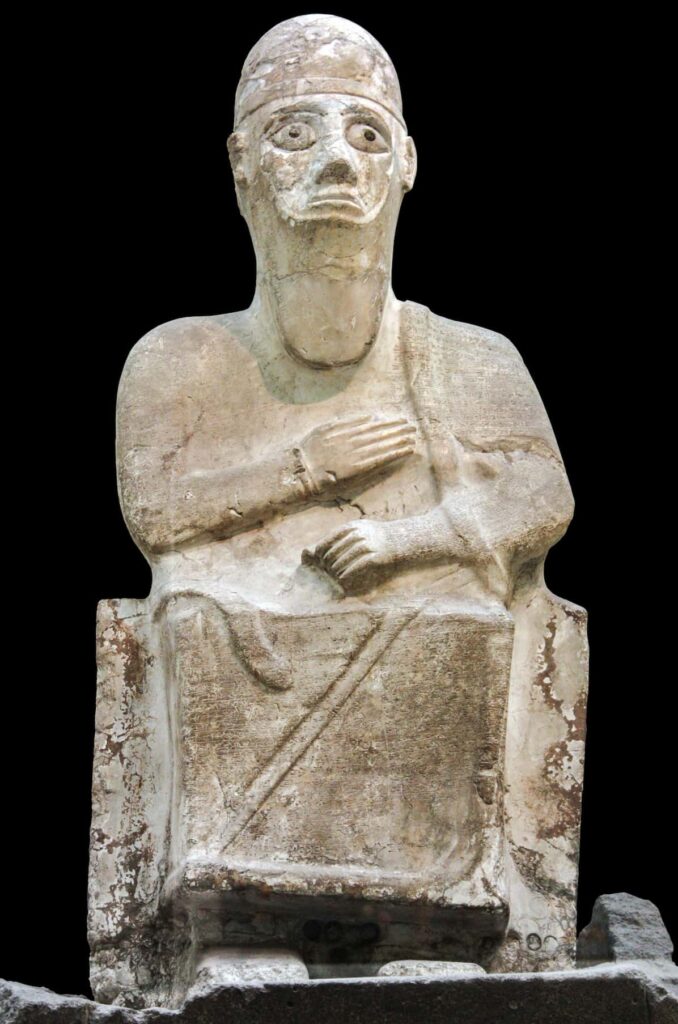

Nuzi, a small Mesopotamian city in the kingdom of Arrapha in what is now northern Iraq, has the names of many people who are classified as Habiru dating back to the 15th and 14th centuries BC. Nuzi attests for the first time that Habiru had been demoted from soldier to servant. Many of them hail from nearby Assyria. One Habiru’s origin is given as “Akkad,” while an Assyrian slave with the name of Warad-Kubi was referred to as a Habiru in an undertaking. It looks like he was a poor foreigner who decided to become a slave. As the mention of a scribe who was also a Habiru demonstrates, Habiru sometimes occupied positions of prominence in society. The name Habiru is usually spelled with a syllabic pattern in Nuzi.

Hittites: 14th–13th century BC

The Habiru were protected people in the Hittite kingdom. They were hired to do manual labor in the fields. Ḫattušili III issued a decree that said anybody from the Ugarit kingdom who entered Habiru’s area would be sent over to the Ugarit authorities.

Known as ilâni SA.GAZ or ilâni habiri, the “gods of the Habiru” are mentioned in thirteen separate Hittite treaties. The presence of references to Habiru deities in official Hittite texts suggests that Habiru were an integral part of ancient Hittite culture. A certain city was taken by the Hurrians and handed to the grandfather of a Habiru called Tette, according to a manuscript detailing an arbitration between the towns of Barga and Carchemish by Mursili II. Habiru led a small kingdom in this instance.

Ancient Egypt and the Amarna Texts: 15th–12th century BC

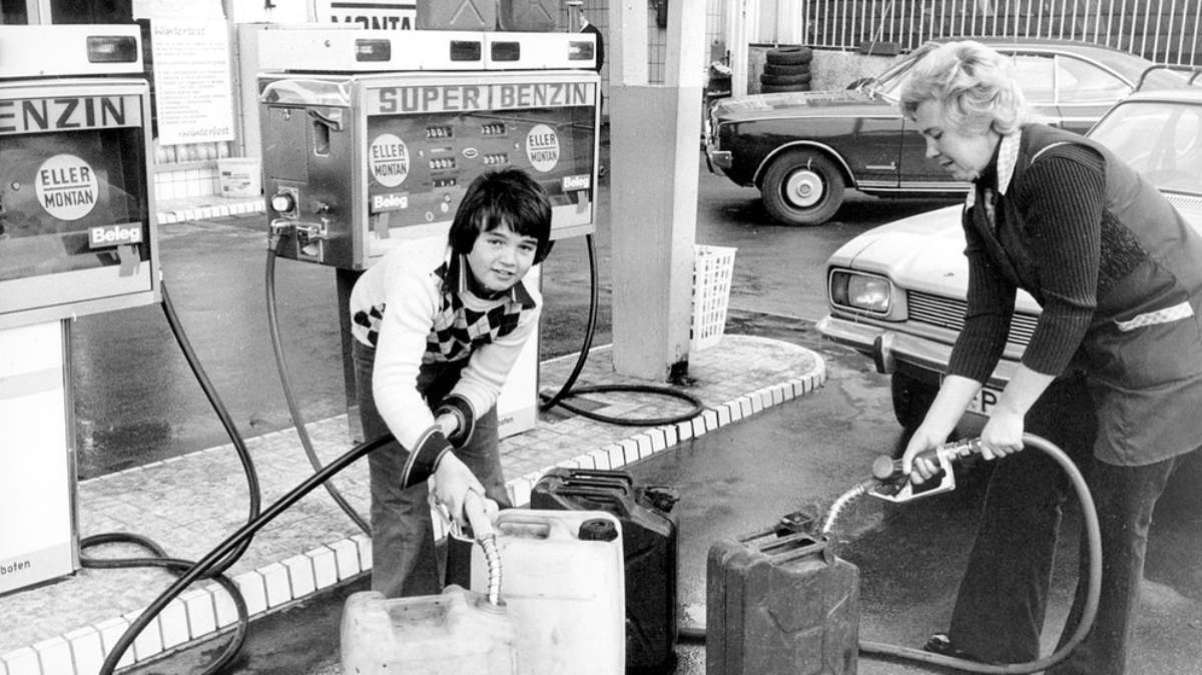

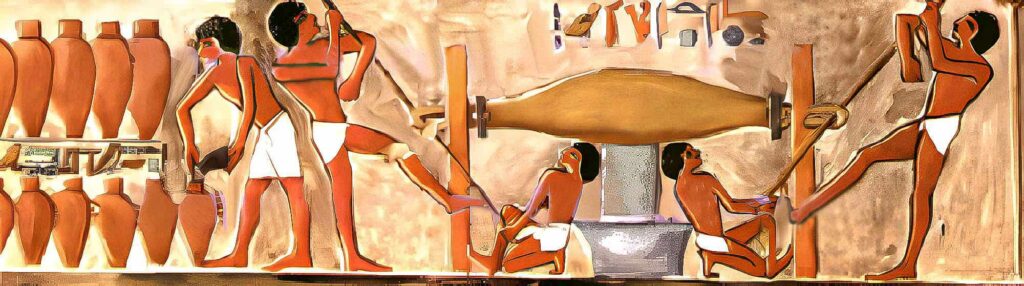

From as early as the 18th Egyptian Dynasty, the “Apiru” (‘pr.w in Egyptian hieroglyphic script) appeared in writings. According to the records, Apiru visited the Middle East during Egypt’s New Kingdom. Amenhotep II boasts that he single-handedly seized 3,600 Apiru. To avoid having his horse stolen by an Apiru, Pharaoh Thutmose III’s commander Thoth asks for it to be kept within the city during the Capture of Joppa in the Papyrus Harris 500. The tombs of Puimre and Tomb 155, both dating to the time of Thutmose III in the Theban Necropolis, have depictions of Apiru engaged in the wine-pressing industry.

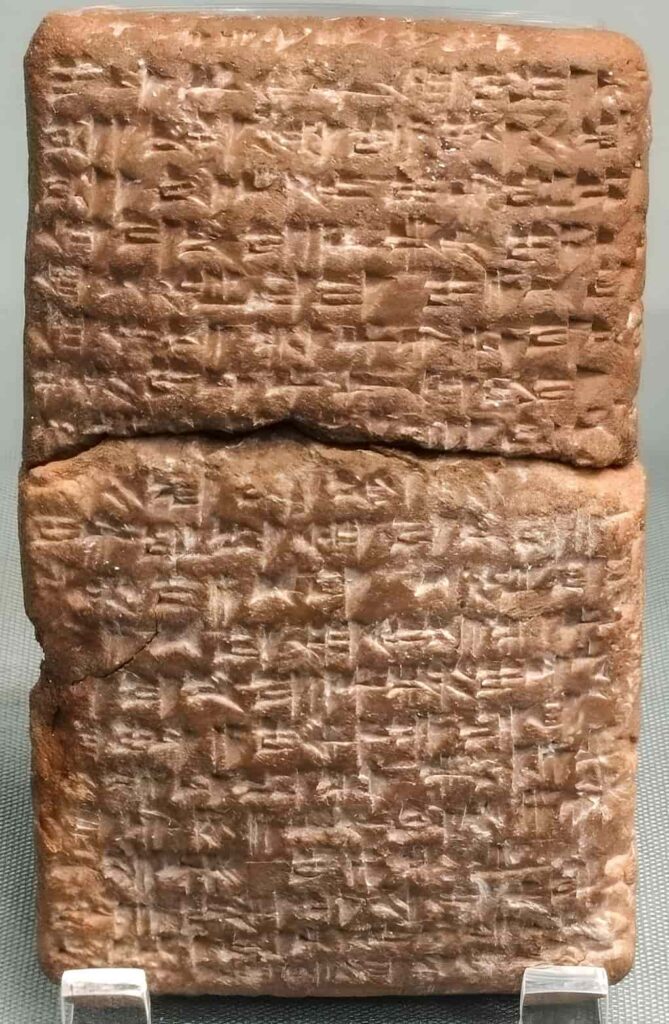

Most of what is known about Apiru or Habiru in the Levant comes from the Amarna Letters. The diplomatic correspondence of Akhenaton (Amenhotep IV) of Egypt, written somewhere about 1340 BC, was sent to him by his vassals among the kings of Canaan and other modern monarchs. The Akkadian cuneiform script was used to write them.

Kings after kings were assaulted by nomadic or semi-nomadic tribes and they wrote to the pharaoh begging for protection.

When fighting regional conflicts, these tribes often established temporary alliances with rival kingdoms. In some scripts, the logogram SA.GAZ designates the Apiru, but in others, the Apiru are referred to syllabically as Habiru. The word might be employed metaphorically on rare occasions to refer to other vassal kings.

The Egyptian towns in northern Canaan were under constant assault from the Habiru throughout the Amarna era. According to the Amarna Letters, the name “Habiru” was used to describe a group of bandits who operated in the hilly highlands of Canaan. The Beqaa Valley seemed to be where they were doing the most damage. The Habiru were traditionally adversarial to Egypt. Damascus did join forces with them once, however, to fight Egypt’s foes. The Habiru were represented in the letters as the paradigmatic bandits.

Invoking them helped justify condemning the violent actions of opponents. If an enemy king’s city was mentioned as joining the Habiru, it could be portrayed as a rebel against the pharaoh. It is not easy to tell whether concerns about the Habiru were a literary ploy to ask Egypt for help or if the Habiru really represented a strong power in Canaan. The Habiru seemed to be loosely organized tribes of nomads who had trouble fitting into Canaanite society at large. They continued to have little impact on regional politics. These bands may have been employed for regional influence methods beyond the rhetoric expressed in the letters.

The Byblos governor (a city in Lebanon), Rib-Hadda, informed the Egyptian pharaoh that the Habiru were aiding the kingdom of Amurru in its growth. Their presence probably didn’t cause any problems for Egypt, and it may have strengthened the ties between Egypt and its vassal countries, who needed its help to fend off Habiru incursions.

The Habiru or Apiru looked to operate on the periphery of urban politics, given that they could not be traced to any one city. However, they were not totally cut off from the metropolitan system, even though they had no links to cities.

They seemed to be involved in the political affairs of the towns of Canaan as well. An Amarna letter (EA 273) provides evidence of diplomatic contact between the Habiru and the towns of Ayyaluna and Sarha, suggesting that the Habiru were involved in political activity.

The Habiru are still being mentioned in contexts beyond the Amarna era. Seti I’s Egyptians went on a mission to Syria and Palestine when the “Habiru from Mount Yarmuta” attacked a nearby city, according to a stele unearthed at Beit She’an, a city in Israel. Slave traders brought back to Egypt an untold number of Habiru.

The determinative sign before the word “Apiru” was often taken to denote nomadic peoples.

So, they were also seen as nomads in the eyes of the Egyptians. Two post-Amarna era Egyptian texts, found in the Kumidu (Kamid el-Loz in Bekaa, Lebanon) administrative center, direct the relocation of Habiru communities from Canaan to Nubia. The Egyptians, Hittites, and Mitanni were all vying for dominance over Syria at the time of these expulsions.

Several slaves, Egyptians, and foreigners, such as the Maryannu (ancient warriors) and Habiru (Papyrus Harris), are included among Pharaoh Ramesses III’s donations to two temples in Heliopolis. Eight hundred Habiru were among the workforce that Pharaoh Ramesses IV sent to the Wadi Hammamat (a river in Egypt) quarries. The Apiru or Habiru is not mentioned again in Egyptian writings after this inscription.

Ugarit: 1300–1200 BC

Ugarit is an ancient port city located in northwest Syria, and the majority of its surviving records are from the late 13th or early 12th centuries BC. These writings show that the Habiru were considered by the government of the kingdom. They were noted in reference to the distribution of oil rations. A “hill of the Habiru” signifies that these people were not nomadic but rather had a fixed location there.

The Many Meanings of Habiru

It is hard to generalize about the ethnicity of those who claim to be Habiru since they all have names with different roots. The names of the Habiru people are either West Semitic or another language, such as Akkadian, Hurrian, or Indo-European.

Meanings of “Habiru” in Society

It became obvious that the Habiru were dispersed all around the fertile crescent when literature describing them was uncovered. These disparate Habiru were not related ethnically or linguistically, and they existed on the outside of established cultures, sometimes operating illegally.

Outlaws, mercenaries, and escaped slaves were depicted in the texts as members of a lower social class. Therefore, according to some observers, Habiru was a socially charged word used to describe those on the fringes of society.

In all extant texts, the word “Habiru” by itself referred to a group of people who lived on the outskirts of settled societies, either raiding them, engaging in combat with them, receiving payment from them to attack others, or else seeking refuge among them and looking for a modest position at the bottom of the social ladder.

Using some Mari texts as evidence, the Israeli archaeologist and historian Nadav Na’aman came to the conclusion that the word Habiru referred to migrants. He pointed out that in Asian societies of the second millennium, the word “Habiru” referred to the act of migration rather than a specific status related to how well the person adapted to their new environment.

They were examples of the dissolution of social cohesion for the sake of undertakings associated with the acquisition of power, similar to an exodus.

The Habiru: Hebrews in Disguise?

The subject of whether or not “Habiru” is related to “Hebrew” has been discussed for over a century, but no clear answer has emerged. Since the 1887 discovery of the Amarna letters, the Habiru have been a major cause of unrest and insurrection across numerous Canaanite city-states, particularly in and around Urusalim (the name of Jerusalem on ancient Egyptian tablets in the 14th century BC; EA 290).

Similarities between the two names, as well as the nomadic lifestyle and geographical and temporal overlaps, led scholars to suggest a link between the Habiru and Hebrews. However, as further references to Habiru were uncovered in the second millennium throughout the fertile crescent, this hypothesis was revised. In 1953, the topic of the Habiru was discussed at the fourth International Association for Assyriology. After it became clear that “Habiru” referred to a group of individuals, several academics gave up on trying to draw connections between the two.

Others point out that the sociological part of the phrase, referring to uprooted people living on the margins of society, is consistent with instances of the Hebrew term in the Old Testament, which were frequently used derogatorily by outsiders. Therefore, although it’s unlikely that all Habiru were Hebrews, it’s plausible that some of their adversaries mistook Hebrews for Habiru.