The Roman Emperor Hadrian is one of the most renowned Roman rulers globally. An iconic figure of the Antonine era, he implemented significant reforms and radically transformed the Roman Empire, concurrently ending the policy of expansion. A patron of the arts and letters, the ruins of his palace in Tivoli vividly portray the zenith of Rome.

However, despite readily conjuring images or portraits of this emperor, the sources about him are scant and problematic. Indeed, Hadrian was not popular among the senatorial classes, and the challenges in his deification process indicate that his actions and personality did not garner unanimous support among the ruling classes.

—>Hadrian’s Wall is a defensive fortification in Northern England, built by the Romans during the reign of Emperor Hadrian. It marked the northern limit of the Roman Empire in Britain

Hadrian’s Little-Known Childhood

Born in Italica (in Baetica, southern Spain) or Rome (sources are contradictory) on January 24, 76, Publius Aelius Hadrianus hailed from a senatorial family with roots dating back to the praetorship of his father, Publius Aelius Hadrianus Afer. The latter, the first cousin of the future emperor Trajan, played a significant role in Hadrian’s early life. Unfortunately, little is known about Hadrian’s childhood.

Following his father’s demise when he was merely ten years old, Hadrian’s education, as reported by the Historia Augusta, was entrusted to Trajan and the Roman knight P. Acilius Attianus. Information about Attianus is scant until his prefecture of the Praetorian Guard, which is attested only from 114 but likely commenced earlier. From this point, a strong bond formed among the three men. Concurrently, Hadrian developed a profound interest in Greek, earning him the Graeculus (“Greekling”). Additionally, he frequently traversed between Rome and Italica during this period.

The Rise of a Provincial

After holding various subordinate magistracies, he began his military career around 94 as a military tribune in the Rhine and Danube provinces. When Emperor Nerva adopted Trajan, he was already standing by Trajan. Nerva, however, kept him at a distance due to false accusations. But with the help of Plotina, he regained favor, became a senator, and then a quaestor in 101.

His military career continued, and he actively participated in campaigns against the Dacians. These campaigns eventually resulted in his appointment as the governor of Lower Pannonia (present-day Hungary and Serbia) in 106, where he successfully repelled Suebians attacks. In 108, he achieved the position of suffect consul. Although he had the unwavering support of Empress Plotina, Trajan still did not adopt him.

He became an important advisor to the emperor. His political journey led him to focus on the eastern provinces of the Empire. In 112, Athens granted him citizenship and the eponymous archonship of the city. On this occasion, they erected a statue for him at the Theatre of Dionysus. The base of this statue is still visible today and provides valuable insights into Hadrian’s rise. Soon after, he had to confront the Parthians in the east and became the legate in Syria (governor) in 117.

—>Hadrian was a Philhellene, meaning he had a strong admiration for Greek culture. He spent a significant amount of time in Greece and even funded the construction of several buildings in Athens.

Coming to Power

The accession to the throne of Hadrian was not without challenges. It was difficult to ascertain whether Trajan clearly designated him as his successor before succumbing on August 8, 117. Cassius Dio argues that this was not the case. He provides a detailed account of how Hadrian assumed the supreme position: “At the time that he was declared emperor, Hadrian was in Antioch, the metropolis of Syria, of which he was governor[…].“

Hadrian wrote to the Senate, seeking confirmation of his rule. He explicitly protested against receiving any honors, a departure from the previous custom where honors were not bestowed unless actively sought. Trajan’s remains found their place under his column. The Parthian games continued for several years but were eventually abolished. Concurrently, Hadrian declined the Senate’s victory in his name and instead celebrated one in honor of his adoptive father, showcasing his deep filial piety.

The succession encountered opposition not only from Cassius Dio but also from significant sections of the dissatisfied Senate. A group of senators perhaps attempted to assassinate the new emperor. Hadrian executed four consuls implicated in the plot without granting them a hearing through his prefect of the Praetorian Guard, Attianus (previously mentioned).

Determining the justification for these executions is challenging; however, these generals from the previous reign undoubtedly posed serious threats to the young prince. This strained relations with the Senate and partly explains Hadrian’s authoritarian exercise of power.

Hadrian’s Passions

With an affinity for hunting akin to that of his predecessor, the personality of this worldly sovereign contrasts sharply with the austerity of the warrior emperor. He neglects his marriage to Sabine and instead opts to maintain relationships with young men, such as Antinous, who accompanies him during his travels. His passion for this young Bithynian was documented in sources recounting the latter’s death by drowning in the waters of the Nile at the age of twenty in 130.

Antinoöpolis (Antinoe) was founded at the site of the tragedy. Hadrian had him deified, which posed some problems since, until then, only members of the imperial family were deified. This cult spread throughout the Empire. Numerous statues today serve as reminders of the extraordinary beauty of this young ephebe and the fervor he inspired. The Pincian Obelisk in Rome is a monument intended for the memory of Antinous and, according to recent research, is believed to originate from Hadrian’s Villa in Tivoli.

Hadrian’s Villa and the Pantheon testify to the emperor’s passion for architecture and the arts. These buildings are masterpieces of Roman art that reflect Hadrian’s ambition for the eternal city. While he restored many structures, inscriptions on them mentioned the original sponsors, posing challenges for historians. These were not mere restorations; the “restored” Pantheon deviated significantly from the original building. Whether it’s the Villa Adriana or the Pantheon, Roman techniques are pushed to their limits and benefit from the latest advances in construction, particularly in cement or opus caementicium.

Hadrian’s interest extended beyond architecture to poetry, literature, and painting. It’s challenging to determine his role in the arts at that time. The numerous statues from Hadrian’s Villa found since the Renaissance, however, provide evidence that he was a significant collector. The emperor’s tastes were eclectic, allowing for the experimentation of innovative artistic combinations.

Stabilizing the Empire

Having participated in numerous campaigns alongside Trajan, Hadrian did not continue the expansionist policies of the previous emperor. His first act was to evacuate Armenia, Mesopotamia, and Assyria, negotiating peace with the Parthians to better defend the Empire.

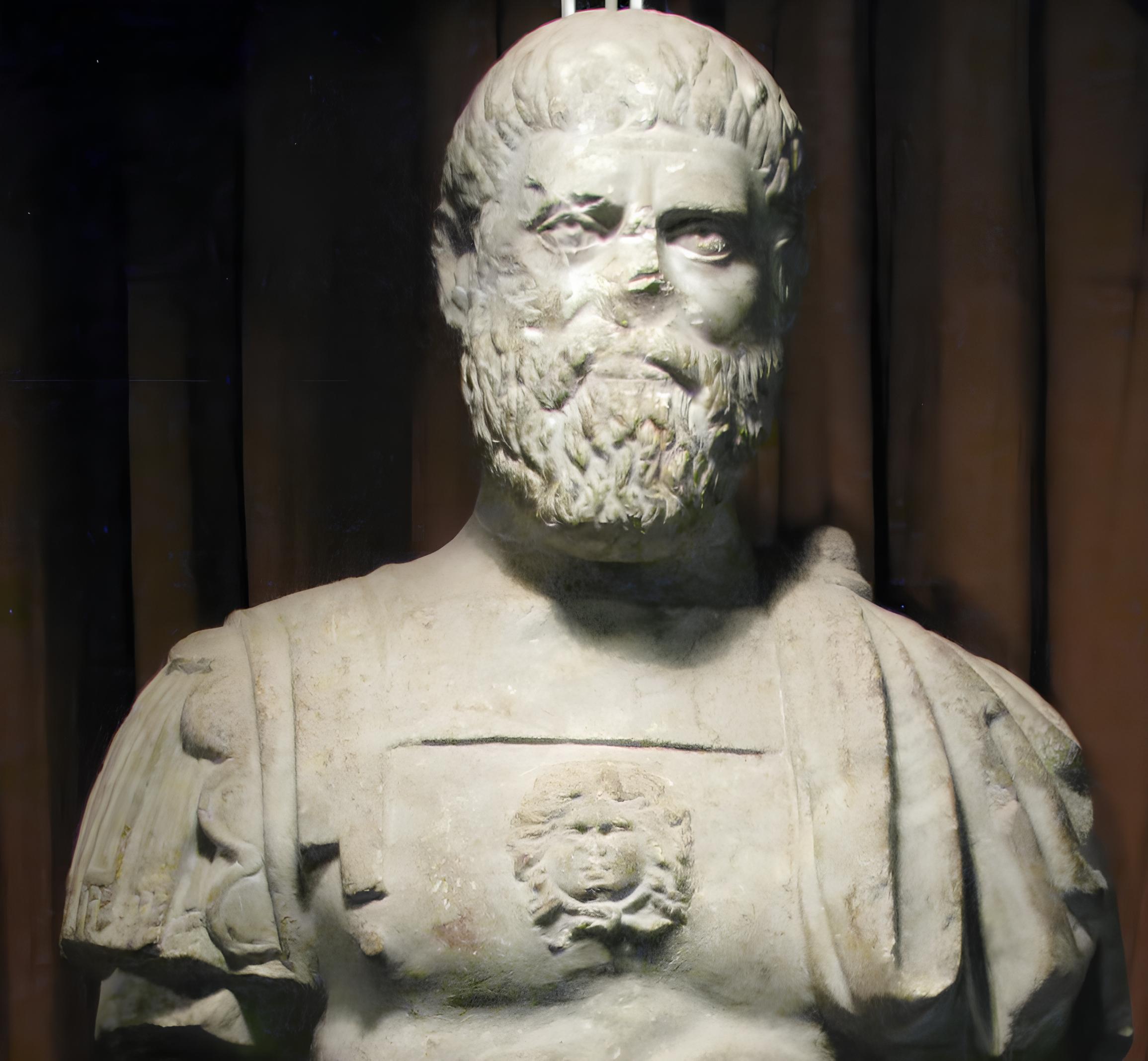

Throughout his reign, he faced uprisings (in Mauretania in 117, in Britain around 120–122, and the Jewish uprising between 132 and 135, which we will delve into later). In Britain, he decided to build a wall that still bears his name today, symbolizing a shift in Roman foreign policy.

Hadrian’s Wall, stretching 80 Roman miles (73 modern miles or 117 kilometers), aimed to showcase Rome’s power in the landscape. It also served as a means for Hadrian to restore discipline within the army by undertaking significant fortification work. By delineating the border, the world was further divided into those who were members of Romanitas and Barbaritas.

The wall also disrupted the seasonal transhumance movements of sheep and cattle between southern Scotland and northern Britain. However, the wall was not entirely impermeable, and contact persisted after its construction. Across the Empire, legions settled and altered recruitment, becoming increasingly localized. Additionally, Hadrian established heavy cavalry units (cataphracts) similar to those of the Parthian Empire.

Coins with the inscription “Disciplina Augusti” remind us of the importance Hadrian placed on the military and the restoration of discipline. The Historia Augusta extensively discusses this policy:

For he reestablished the discipline of the camp, which since the time of Octavian had been growing slack through the laxity of his predecessors. He regulated, too, both the duties and the expenses of the soldiers, and now no one could get a leave of absence from camp by unfair means, for it was not popularity with the troops but just deserts that recommended a man for appointment as tribune.He incited others by the example of his own soldierly spirit; he would walk as much as twenty miles fully armed; he cleared the camp of banqueting-rooms, porticoes, grottos, and bowers, generally wore the commonest clothing, would have no gold ornaments on his sword-belt or jewels on the clasp, would scarcely consent to have his sword furnished with an ivory hilt, visited the sick soldiers in their quarters, selected the sites for camps, conferred the centurion’s wand on those only who were hardy and of good repute, appointed as tribunes only men with full beards or of an age to give to the authority of the tribuneship the full measure of prudence and maturity, permitted no tribune to accept a present from a soldier, banished luxuries on every hand, and, lastly, improved the soldiers’ arms and equipment. Furthermore, with regard to length of military service he issued an order that no one should violate ancient usage by being in the service at an earlier age than his strength warranted, or at a more advanced one than common humanity permitted. He made it a point to be acquainted with the soldiers and to know their numbers.

Source: Historia Augusta

Harmonizing the Empire

Hadrian spent half of his reign traversing the provinces, not for tourist reasons but for political ones. Under his vision, the Empire should no longer be merely the dominance of Rome over the Mediterranean periphery but rather an association of provinces sharing a common destiny. The coins, through numerous references to the provinces, illustrate the genuine consideration of the imperial power of the provinces.

This is not mere rhetoric; in Spain, epigraphic documents have been found mentioning regulations in agriculture or mining from that time. His travels to the East reveal a particular attraction to this part of the Empire and to Hellenism. In this perspective, he seeks to better integrate the Hellenophone elites by establishing the Panhellenion in Athens, a religious institution aiming to unite all Greeks.

Furthermore, he undertook the restoration or construction of numerous buildings and created new cities like Hadrianoutherai (Balıkesir), Adrianople (Edirne), or Antinoöpolis in the place where Antinous succumbed in Egypt. Benevolence during his reign flourishes. Contrary to a widespread notion, Hadrian does not accelerate the integration of provincial elites into the Senate (already well underway under Trajan); on the contrary, it regresses significantly.

Unlike popular belief, the progress of Easterners was halted during his reign. However, he promotes the integration of African elites into the Senate. These actions aim to harmonize the Empire by transforming the provinces from being merely Rome’s hegemonic possessions to being vital parts of it, adding to Rome’s glory and prosperity.

Reforming the Empire

Hadrian significantly reformed the empire. He divided Italy into four districts, assigning them to consulars (former consuls), thereby diminishing a senatorial prerogative. These senators administered justice in these districts, replacing the peregrine praetor. This administrative reform accompanied a substantial change in the recruitment of officials: the equestrians took up high positions in the administration, replacing freedmen who were relegated to subordinate roles.

In terms of jurisprudence, in 131, he enacted the Praetor’s Edict of Publius Salvius Julianus, compiling the previous praetorian (from praetors) and curule (from curule aediles) edicts. This edict was indefinitely valid thanks to a senatorial decree.

A genuine legal code was adopted, further rationalizing Roman law and breaking away from the traditional Praetorian edict that had to be promulgated annually (although in practice, they often reissued the edict of their predecessors with modifications).

The emperor surrounded himself with numerous eminent jurists who composed the imperial council. Through his numerous rescripts, he became the authority in judicial matters. Hadrian’s work aimed at strengthening imperial power. This centralizing policy faced significant resistance from senatorial circles as opposed to an emperor who conceived his power in a too monarchic manner. In this regard, he continued the policy initiated by Claudius or Domitian, which also caused them some trouble.

The Troubled End of Hadrian’s Reign

Following the deterioration of relations between the Jews and the Romans brought about by the construction of a Jupiter temple in Jerusalem at the location of the Second Temple, which the Romans destroyed in 70, Hadrian had to contend with a revolt in Judea from 132 to 135 under the leadership of Bar-Kokhba.

The repression results in numerous casualties and concludes with the destruction of the city of Jerusalem. The colony of Aelia Capitolina succeeds it. Hadrian reorganized the province, renaming it Syria and Palestine, and increased the number of troops in the garrison. The emperor’s letter to the Senate and refusal of a triumph in Rome serve as examples of how deeply affected he was by these events.

After these events, he dedicated his final years to organizing his succession. He wrote an autobiography for his successor, now lost except for a fragment of Egyptian papyrus. The old man builds his mausoleum (the current Castel Sant’Angelo) and adopts, in 136, the socialite Lucius Aelius Verus, who, though not a prominent figure of his time, holds the title of consul.

Hadrian quickly confers upon him the title of Caesar, the tribunician power, and the governance of Pannonia. The reasons for this choice remain unclear today. Death strikes his wife Sabine and then the designated successor on January 1, 138, disrupting his plans.

—>Hadrian died of heart failure on July 10, 138 AD, in his villa in Baiae. He was succeeded by Antoninus Pius.

Hadrian revises his plans, adopting the former proconsul of Asia and a member of the Imperial Council, Titus Aurelius Fulvius Antoninus Boionius Arrius, the future Antoninus Pius. He grants him the tribunician power and the title of Caesar, owing his ascent to loyalty to the emperor. However, he was compelled to adopt Lucius Aelius Verus, the son of the recently deceased heir, and the 17-year-old Marcus Annius Verus, the future Marcus Aurelius, whom Hadrian had knighted a decade earlier.

Numerous family ties connect these various heirs. This succession is not just a selection of the best contenders for the throne but a consolidation of a dynasty and a resolution of political issues. The complex succession also reveals that Hadrian believed his successor’s reign would be short and that the true designated heirs were still too young to rule (Lucius Verus was only 8 years old in 138). He died in Baiae on July 10, 138. Antoninus Pius, the new emperor, faces significant challenges in deifying his predecessor.

Hadrian is one of the most significant emperors of the 2nd century, radically transforming the Empire in many aspects. Despite being disliked by the senatorial elites for his monarchical exercise of power, this aesthete, in a way, foreshadows the era of the Severans in the early 3rd century. Some of his achievements may not endure, but the Pantheon and Hadrian’s Villa remain inextricably linked to his legacy and that of Rome.

Hadrian’s Travels

From Syria to Rome (117–118 CE)

Hadrian’s first journey commenced shortly after he assumed the role of emperor, succeeding his adoptive father and predecessor, Trajan. Trajan’s conquests in the east had led to the enlargement of a substantial yet precarious empire, an inheritance bequeathed to Hadrian. Opting to relinquish control over these territories, he directed his attention towards fortifying the existing borders. Traveling from Syria, where news of his ascension reached him, to Rome, Hadrian traversed through Anatolia, Greece, and Illyria.

During his journey, the emperor inspected the army, administration, and infrastructure of the provinces and showed great interest in local cultures and religions, especially Greek culture, which he admired and supported. The emperor’s arrival in Rome in July 118 AD was greeted with mixed feelings by both the senate and the people.

From Rome to Britain (121–126 CE)

Hadrian’s second journey was the longest and most famous of his travels. He left Rome in 121 CE and headed north, crossing the Alps and visiting Gaul, Germany, and the Rhine frontier. He then reached Britain, where he ordered the construction of a massive wall along the northern border of the province to protect it from the raids of the Picts and other tribes. The wall, which stretched for about 120 km, was a remarkable engineering feat, and it still stands today as a testimony to Hadrian’s legacy. Hadrian also visited other parts of Britain, such as London, Bath, and York, where he improved the urban and military facilities.

After spending about three years in Britain, Hadrian resumed his journey and traveled south, through Gaul and Spain, his native land. He then crossed the Mediterranean and arrived in North Africa, where he visited the provinces of Mauretania, Numidia, and Africa. He paid special attention to the city of Carthage, which he rebuilt and embellished after its destruction by the Romans in the Punic Wars. He also inspected the agricultural and economic situation of the region and granted privileges and donations to the local communities.

From Africa to the East (128–134 CE)

Hadrian’s third journey took him from Africa to the eastern provinces of the empire, which were the most populous and prosperous but also the most turbulent and diverse. He sailed from Carthage to Alexandria, the cultural and intellectual capital of the east, where he spent some time enjoying the wonders of the city. He also visited the famous Serapeum, a temple dedicated to the Egyptian god Serapis, which he may have rebuilt after a fire. He then traveled along the Nile, admiring the ancient monuments and the natural scenery of Egypt. It was during this trip that he lost his beloved companion, Antinous, a young Greek boy who drowned in the river. Hadrian was devastated by his death, and he deified him and founded a new city in his honor, Antinopolis.

From Egypt, Hadrian moved to Judea, where he faced a serious rebellion by the Jewish population, who resisted Roman domination and the imposition of pagan cults. Hadrian crushed the revolt with brutal force, killing or enslaving thousands of Jews and renaming the province Syria Palaestina. He also rebuilt Jerusalem as a Roman colony and erected a temple to Jupiter on the site of the former Jewish temple.

Hadrian continued his journey through Syria, Asia Minor, and Greece, where he participated in the Eleusinian Mysteries, a secret religious initiation that he had long desired to join. He also visited Athens, his favorite city, where he completed several building projects, such as the Temple of Olympian Zeus, the Arch of Hadrian, and the Library of Hadrian. He also founded a new institution, the Panhellenion, a federation of Greek cities that aimed to revive the glory and unity of the Hellenic world under his patronage.

The Return to Rome and the Final Years (134–138 CE)

Hadrian returned to Rome in 134 CE, after more than a decade of traveling. He was exhausted and ill, and he devoted his last years to the administration of the empire and the succession of his adoptive son and heir, Antoninus Pius. He also built his magnificent villa at Tivoli, a complex of palaces, gardens, and artificial lakes where he recreated some of the places he had seen during his travels. He also commissioned his mausoleum, a circular tomb on the banks of the Tiber, which later became the Castel Sant’Angelo. He passed away in 138 CE at the age of 62, and his wife Sabina and his beloved Antinous joined his ashes in his mausoleum.