The harpax (Greek: ἅρπαξ) was the designation for a Roman naval weapon used for long-range capture of an enemy ship to attach to it and decide face-to-face combat. It was a long and heavy harpoon, with a grapnel attached at one end and a long rope at the other. It was launched by a ballista, and once hooked, it was pulled by the attacking ship using a winch (like a windlass). The harpax is credited to have been invented by Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa, the commander of Octavian’s fleet, and was first successfully used in the Battle of Naulochus (36 BC) against Sextus Pompey’s fleet.

The First Appearance of the Harpax in Battle

Its first appearance in a naval battle occurred on September 3, 36 BC, in the Battle of Naulochus, where Octavian’s new fleet faced Sextus Pompeius’ fleet. The results of the battle demonstrated the significance and effectiveness of the “harpax” in naval combat.

Battle Results:

Sextus:

- 17 ships managed to escape with Sextus.

- 28 ships were sunk.

- 135 were captured by Agrippa’s fleet.

Octavian:

- 3 ships were sunk.

The Harpax in Historical Sources

We only have knowledge of the iron hook fired from a catapult and called “harpax” from one source: Appian, the Greco-Roman historian from the 2nd century AD. He writes that leading up to the naval battle at Naulochus between Agrippa and Pompey, each side prepared 300 ships.

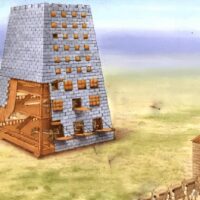

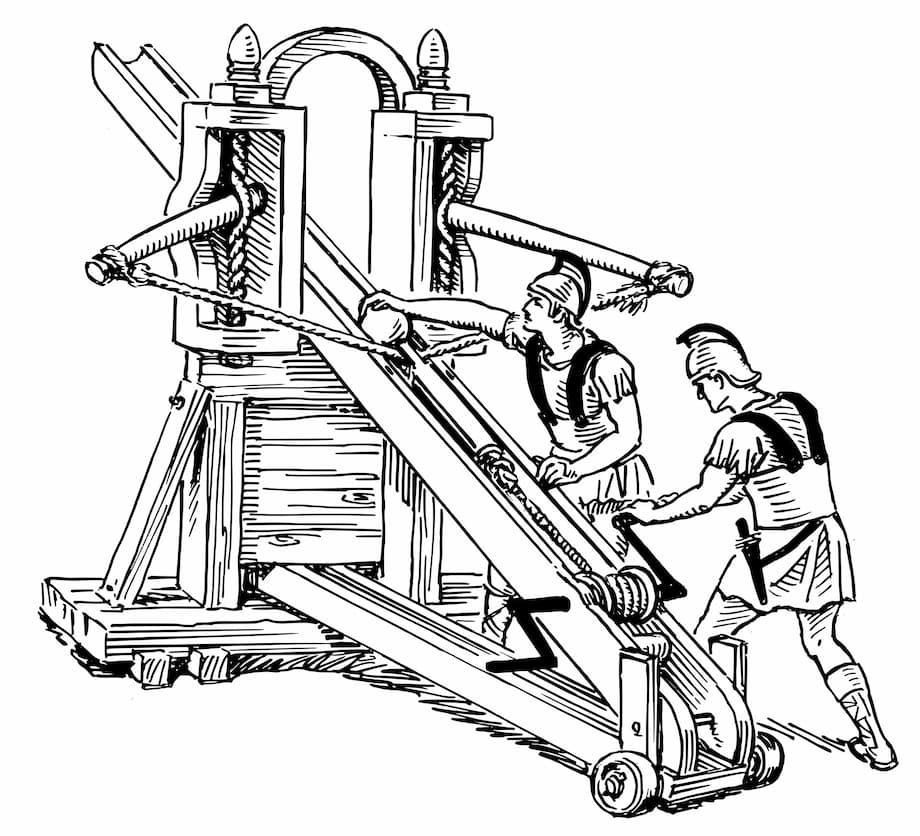

“These ships…carried various types of siege engines, towers, and all the devices that each side thought fit to set up. Agrippa invented a machine called the harpax (ἁρπάγη), a grapnel five cubits long reinforced with metal rings, with a ring at each end. One ring was attached to the harpax, an iron grapnel, and the other ring to double ropes. The harpax was fired by a catapult, and after catching an enemy ship, it was pulled by the machine.”

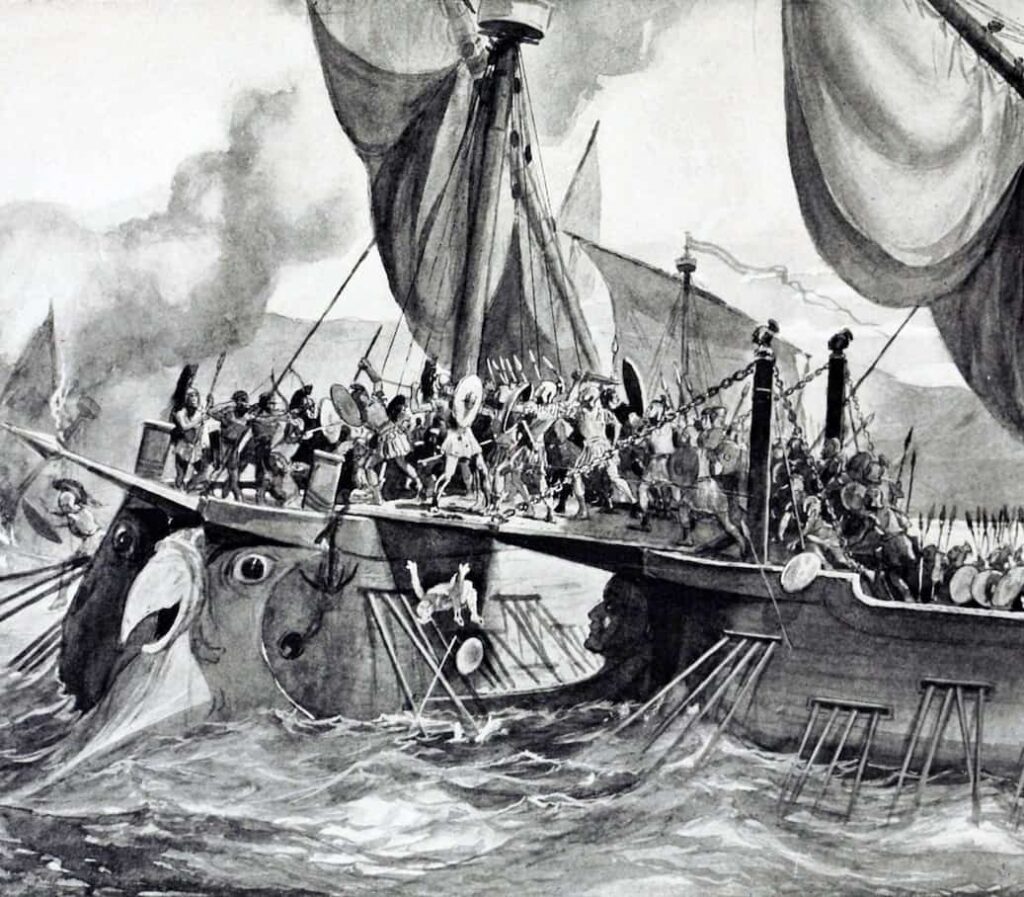

On the appointed day, both sides positioned their ships in a straight line for battle. Upon receiving the signal, ships from both camps rushed headlong toward each other, and during the strenuous rowing, they showered their enemies with javelins, stones, burning braziers, and arrows, some of which were shot from catapults and others thrown by hand. When the distance was narrowed, the ships collided. Some ships rammed the sides of their opponents, while others broke through the center of the formation, all the while firing missiles and throwing darts. The main effort was to disable the movement of the rival ship or to seize it in order to decide whether to engage in face-to-face combat with the soldiers on the ship.

“The harpax achieved the greatest success,” says Appian.

“It could be thrown onto the enemy ships from a great distance due to its low weight, and when pulled back with the ropes, it held on firmly. Because of the iron hook’s grip, people couldn’t easily detach it, and its length made it difficult for them to cut the ropes. Since this device was unfamiliar to them before, and therefore they did not counteract it with poles at the ends like levers, they could do nothing in this unexpected situation except to retreat to resist the pull. But since the enemy did the same, the efforts on both sides were equal, and the harpax did its job.”

The Roman Navy until the Punic Wars

Until the First Punic War in 264–241 BC, the Roman navy was relatively small and undeveloped, consisting of a small number of ships whose main role was patrolling rivers and the shores of Rome and its surroundings. The primary naval warfare strategy involved grappling with enemy ships and minimal archery. This method required agility and speed superior to those of the adversary.

Rome in the Punic Wars and the Development of the Corvus

With Rome’s entry into the First Punic War against Carthage, there arose a need for a large and modern navy that could withstand the Carthaginian fleet and its superior maneuverability.

The Romans entrusted the construction of their ships to their allies due to their lack of experience in building warships. The innovation that the Romans introduced to their warships to counter the Carthaginian fleet was the “corvus” or “raven.

“

The Corvus (Boarding Device)

The “corvus” was a naval attack device consisting of a boarding bridge that captured the enemy ship when it was close and allowed the Roman infantry to seize control of it. The rationale behind this device was the understanding that the Carthaginian navy was faster, had better maneuverability, and had more experience than the Roman navy. Rome’s advantage lay in its infantry, so by neutralizing the navigation ability of Carthaginian ships using the “corvus,” the Roman infantry could take control of the enemy ships.

Polybius provides a description of the “corvus” in his history books, stating:

“Since their ships were unsteady in structure and slow, they fitted them with an auxiliary fighting machine called later the ‘corvus’, constructed as follows: on the prow of the trireme, they set up a round pole, seven meters in height, and the diameter of its base was twenty-two centimeters. On top of it was mounted a pulley, and around it was a camel made of two and a half-inch-thick planks, twenty-two meters in width and ten and a half meters in length. It had a hole lengthwise through which the pole was inserted, set about three and a half meters from the inner end of the camel. On both long sides of the camel was a railing the height of a man’s knee. At the outer end of the camel was fixed a piece of iron similar to a sharpened plowshare, with a ring at its head, resembling an instrument used for threshing grain. To this ring was fastened a rope, and during a battle, when the ship was grappled, they lifted the ‘corvus’ by means of the pulley, with the grain-threshing instrument hanging down, and dropped it onto the deck of the enemy ship through the hole in the camel. Then they hauled it up against the side with ropes during the engagement, either running it into the enemy’s side through the railing on the camel or swinging it around to meet attacks from the side.”

Maritime Development from the Punic Wars to the Battle of Naulochus

The evolution of naval warfare from the Punic Wars until the Battle of Naulochus witnessed the efficacy of the “corvus” in the First Punic War, leading to Roman triumphs over the Carthaginian fleet. However, beyond victories over the Carthaginian navy, the device revealed its drawback by unbalancing Roman ships during open-sea maneuvers, resulting in more Roman ships sinking than being lost in battles. Following two severe disasters in 255 and 253 BC, where the Roman fleet lost half its strength due to the instability caused by the “corvus,” it was decided to abandon its usage.

After the Punic Wars, larger warships were developed, capable of carrying more weaponry, such as ballistae, and soldiers. During the conflict against Sextus Pompeius in Sicily, Octavian entrusted Agrippa with the task of rebuilding the navy after it suffered severe damage.

Agrippa, as part of the preparations, trained and prepared the Roman fleet for war against Sextus Pompeius in western Sicily. In this process, the “harpax” was introduced.

The Harpax and its Characteristics

The “harpax” served the same purpose as the “corvus,” connecting two ships for boarding but with numerous improvements enhancing Agrippa’s fleet’s military capabilities. Described by Appian, the “harpax” was a device consisting of a wooden pole about 7.2 feet long, reinforced with iron rings to prevent easy breakage. Launched from a ballista mounted on the ship’s stern, the side facing the enemy ship was equipped with an iron ring containing sharp hooks. These hooks were intended to embed into the enemy ship. On the other side of the “harpax,” there was an additional ring to which ropes were attached. After the hooks were embedded in the enemy ship, the crew pulled the ropes, drawing the enemy ship closer for boarding.

Subsequent Use of the Harpax in Octavian’s Fleet

Following the Battle of Naulochus, the harpax continued to be a central tool in Octavian’s fleet. It was also deployed in the final naval engagement, the Battle of Actium.

In this battle, Octavian emerged victorious over the fleet of Marcus Antonius and Cleopatra, thereby eliminating the last threat to his authority in the Roman Empire.