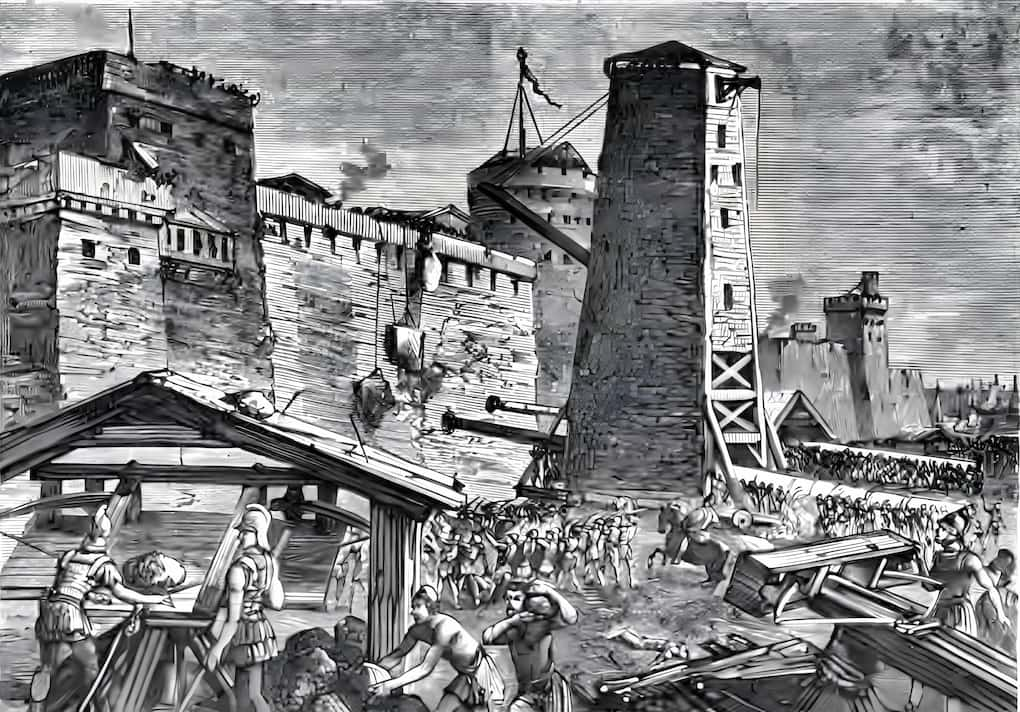

The Helépolis or Helépola (in Greek ἑλέπολις, city taker or conqueror) was an ancient siege engine, specifically a type of large-scale siege tower or bastion developed during the reign of Alexander the Great. It was used with great success in the sieges of various cities during the Hellenistic period. The most famous one was built by Epimachus of Athens for Demetrius I of Macedonia to besiege fortified locations. Helépolis was valuable for the artillery concentrated within it, particularly the various-caliber artillery pieces that adorned all its floors.

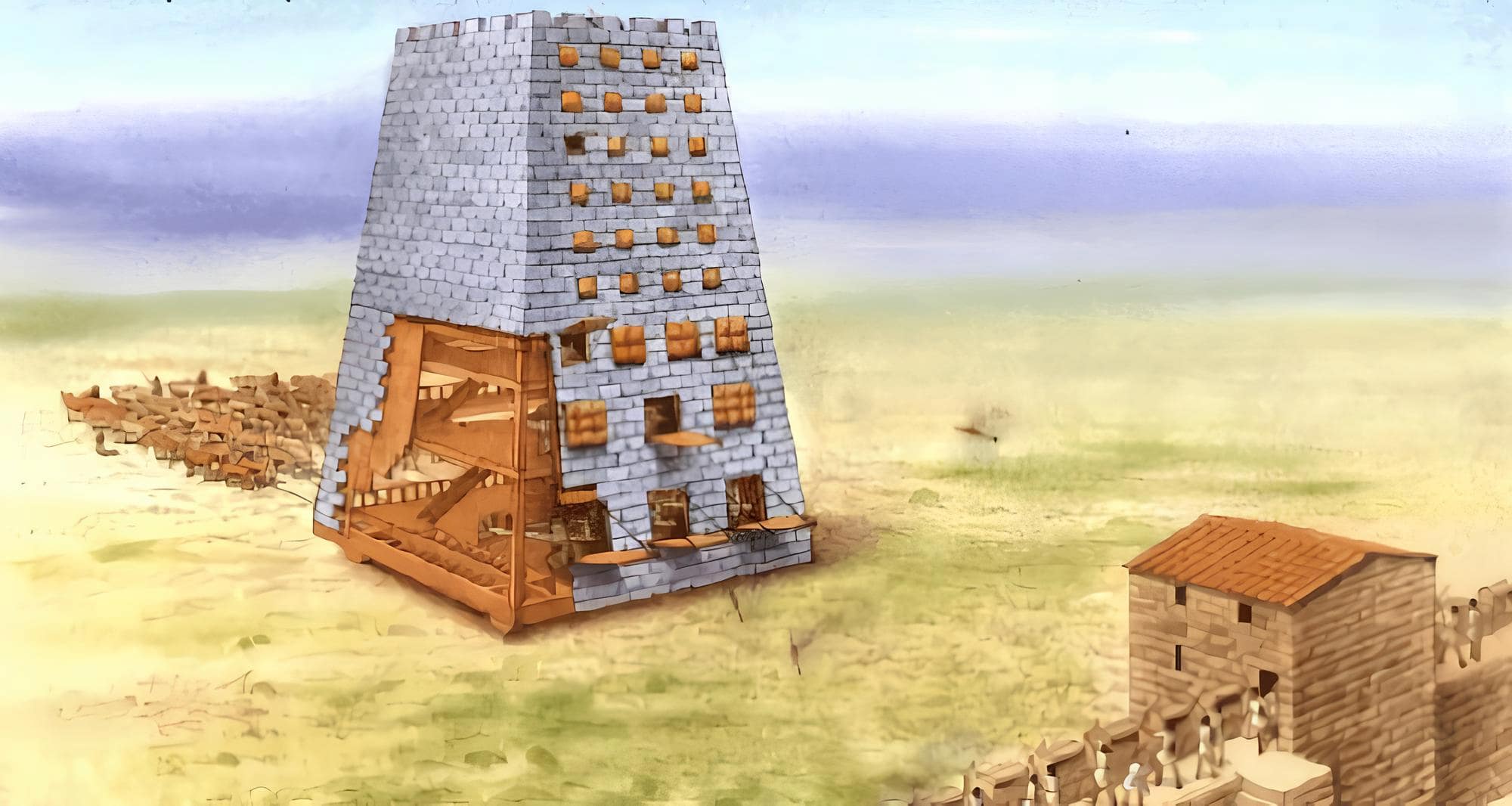

According to Biton, the Macedonian Posidonius, during Alexander’s reign, built one that was 14.50 meters tall. The majority of the structure was made of wood, pine and fir for partitions, oak and ash for rolling elements, axles, wheels, props, and main beams. On the penultimate floor, there were cantilevered bridges equipped with rigging to hoist them.

Large wheels were placed between the beams of the base platform in a vertical position, similar to hamster wheels, capable of driving the tower’s driving wheels. They served as a support device after the tower was brought close to the wall.

The First Helépolis of Demetrius Poliorcetes

When Demetrius Poliorcetes was about to besiege Rhodes, he proposed constructing a machine called the City Conqueror. Its shape was that of a square tower, resting on four wooden wheels. It was divided into nine floors: the lower ones contained machines for launching large stones; the middle floors housed large catapults for spear-throwing; and on the upper levels, there were other machines for hurling smaller stones along with smaller catapults. In addition to those who turned the sizable winch that drove the wheels through a belt, 200 soldiers operated it. It proved to be very slow but very powerful.

The City Conqueror

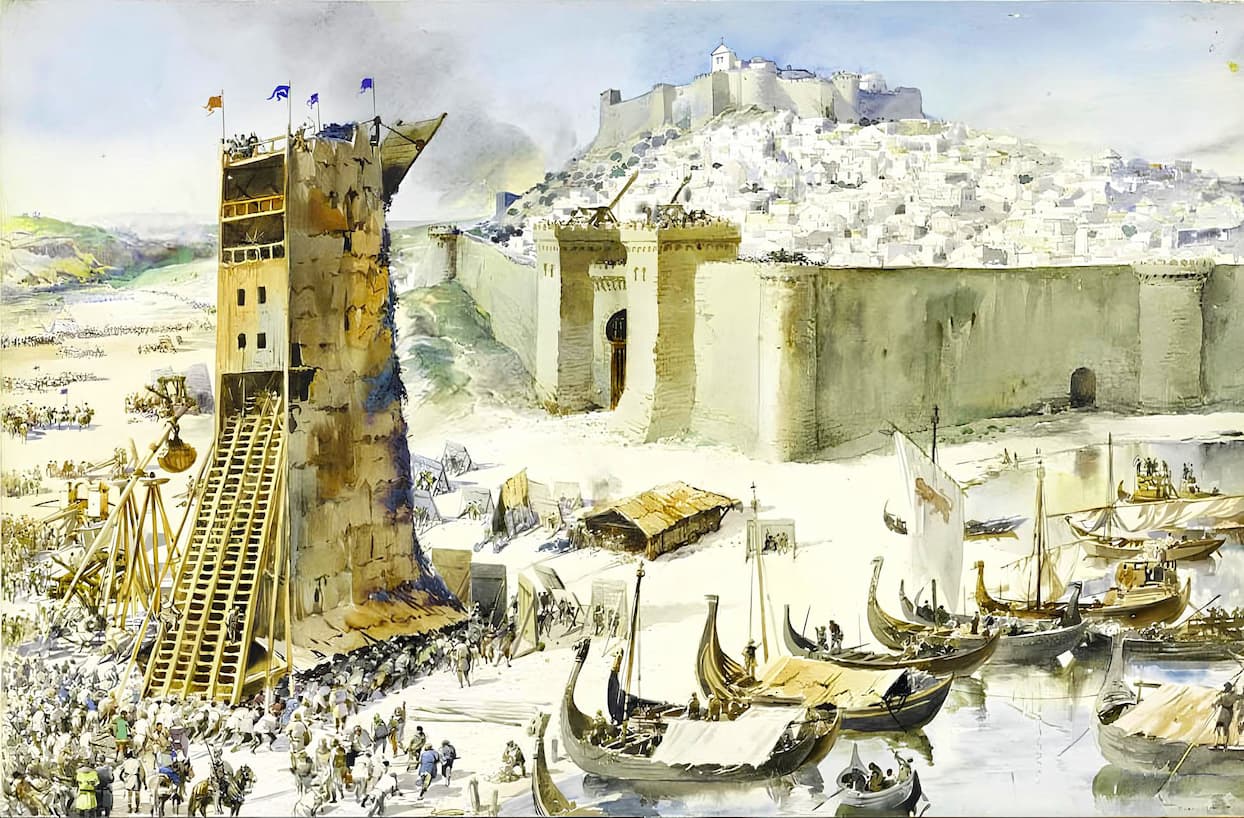

During the significant siege of Rhodes (305 BC–304 BC), Demetrius employed a Helépolis against the defenders of Rhodes, of even larger dimensions, complicating the construction after attempting to mount two of them in the harbor on two pairs of ships.

The new Helépolis, in addition to eight enormous solid wheels with wooden covers nearly a meter thick, also had pivot wheels to allow lateral movement and lighten the pressure of this structure on the ground. Its shape was that of a large pointed tower, with sides measuring about 41.1 meters in height and 20.6 meters in width, surpassing the towers of the walls of Rhodes.

Parallel beams, with less than half a meter of separation, forming part of the lower floor, could accommodate nearly a thousand men between them to propel it from the inside.

Many more were needed outside to give it speed. Diodorus Siculus says that 3,400 soldiers, the strongest, were selected to move the Helépolis.

The three sides exposed to attack were heat-resistant and protected with iron plates in case the Rhodians attempted to set it on fire. At the front of each floor was a gate, protected by shutters made of skins covered with wool, which could be mechanically opened or closed to cushion the impacts of stone projectiles thrown by the defenders.

Each of the nine levels had two wide staircases for both ascent and descent. On each floor were weapons that launched projectiles, such as ballistae and catapults, the smallest ones and larger ones on other levels. On the upper floors were stone throwers (litobolos) and a whole series of launching machines, such as oxibels (huge and evolved gastraphetes) and ballistae that fired both arrows and javelins and were lighter than catapults. On the lower floors, catapults and other launching machines for immense stone projectiles, weighing almost 90 kg, were installed.

In summary, this Helépolis was an immense siege tower that required more than half a kilometer of cleared and terraced ground up to the walls. It rolled at a higher speed than its “smaller counterparts,” featured multiple levels of platforms with various launching machines, and was an exceedingly effective siege engine, even though it lacked protruding overhangs and ramps from which troops could launch assaults on enemy fortifications.

Epimachus of Athens constructed the Helépolis, and Diekles of Abdera provided a faithful description of it. Undoubtedly, it has been the most significant and remarkable contraption of its kind ever erected. Another, more comprehensive description is provided by Diodorus Siculus:

Having gathered a certain amount of varied materials, he had a machine built called Helépola, much larger than the previous ones. Indeed, he gave each side of the square platform a length of about 50 cubits (22.20 m), constructing a set of square-sectioned wooden pieces joined with iron. He compartmentalized the interior space with partitions spaced about a cubit (44.40 cm) apart so that those who were to push the machine forward could fit. The entire mass was mobile, supported by eight solid and large wheels; their wooden rims were two cubits thick and surrounded by sturdy iron plates. For lateral movements, inverters were arranged, allowing the entire machine to be easily displaced in any direction. At the corners, there were masts of equal length, slightly less than 100 cubits, inclined so that in the nine-story structure, the first had an area of 43 scenes, and the last had nine. Three faces of the machine were externally covered with nailed iron plates to prevent incendiary arrows from causing any damage. On the side facing the enemy, the floors had windows whose size and shape were adapted to the characteristics of the projectile engines to be used; the windows had shutters that could be raised by a machine, ensuring the protection of those responsible for the service of throwing weapons on different floors, as these shutters were coated with skins and filled with wool to cushion the blows from stone throwers (litobolos). Each floor had two staircases; one was used to bring up the necessary materials, and the other for descent, so that the entire service could be carried out without disorder. Those tasked with moving the machine were chosen from the entire army for their strength and totaled 3,400; some were enclosed inside, others positioned behind and at the sides, all pushing the machine forward, whose movement was greatly facilitated by technical procedures.

After the siege, the machine was abandoned, and the people of Rhodes melted down its metal plates. With the materials, they constructed the Colossus of Rhodes. Subsequently, the name Helépolis was applied to mobile towers that transported battering rams, as well as machines for launching spears and stones.