Henry II, King of France from 1547 to 1559, is best known for his tragic death following an eye injury sustained during a tournament. The son of King Francis I and Claude of France, he married Catherine de’ Medici, a wealthy Florentine aristocrat. Shortly after their marriage, he took Diane de Poitiers as his mistress, a woman who would significantly influence the king’s policies after his accession to the throne in 1547. Henry II continued the war waged by his father against Charles V, the Holy Roman Emperor, but with no greater success. He also attempted to eradicate the Protestants.

After his death, three of his sons reigned during the French Wars of Religion: Francis II, Charles IX, and Henry III.

The Unhappy Childhood of Henry II

Born in Saint-Germain-en-Laye in 1519, Henry II was the second son of Francis I and Claude of France. Francis I hardly prepared his son to rule, preferring his younger brother, Charles of Orléans, who died of the plague in 1545. However, from a young age, Henry faced the harsh reality of being a prince. The Treaty of Madrid (1526) included the taking of Francis I’s two eldest sons as hostages.

Thus, Henry, at the age of seven, was forced to live for four years in detention in Villalba and then in Villalpando, Spain. This experience, endured in dreadful conditions, permanently shaped his austere and reserved character.

Upon his return to France, Henry’s education was entrusted to Diane de Poitiers by Francis I. The young woman won the affection of the prince, and even after his marriage to Catherine de’ Medici in 1533, Diane’s influence over Henry continued, eventually becoming his mistress. In 1536, the death of his elder brother Francis made Henry the dauphin of France. He ascended the throne after his father’s death on March 31, 1547.

A Young King Under Influence

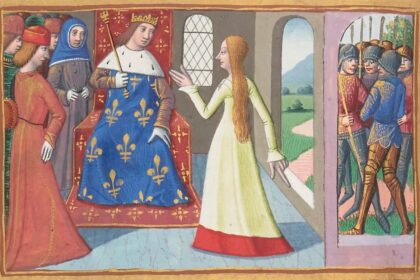

Before his coronation at Reims on July 26, 1547, Henry II had already taken control of the government. He began by reforming courtly behavior, and in 1548 organized an expedition to Scotland to rescue the young Mary, Queen of Scots, from Protestant clutches. Henry II arranged for the young queen to be betrothed to his eldest son.

He also sent his favorite, Charles de Brissac, to gauge the intentions of Charles V. As strong in appearance as he was weak in character, the young king was influenced by several conflicting forces: Diane de Poitiers, Catherine de’ Medici, the Guise family, and the constable of Montmorency.

Henry II enlisted the service of Anne de Montmorency, who had fallen out of favor during the previous reign but was now rehabilitated as the king’s chief advisor. This arrogant, jealous, and staunch advocate of peace frequently clashed with the war-ready Guise family, the Cardinal of Lorraine, and the Calvinists. Throughout his reign, Henry II was caught between the intrigues of the Guise and Montmorency, and the counsel of his beloved mistress, Diane de Poitiers, satisfying his taste for controversies.

Domestic Reforms

Internally, Henry II established four State Secretariats to manage the geographical division of France. These officials handled military, financial, and judicial matters within their districts. In 1551, under the guise of relieving the parliaments, but with the true aim of fiscal management, Henry II created the présidiaux, courts that held judicial authority over bailiffs and seneschals.

This increase in judicial institutions encouraged litigation, already widespread, but did nothing to address the sluggishness of the justice system. Fiscal revolts, which were frequent, were harshly suppressed. By the end of Henry II’s reign, public debt had already reached 43 million livres tournois.

Henry II Against the Empire

In foreign policy, Henry II naturally focused more on France’s northern and eastern borders than on Italy. Humiliated during his childhood imprisonment by Charles V during the Italian Wars, he sought revenge upon becoming king.

He fought against the German princes of the Schmalkaldic League and, by allying with the Protestant German princes rebelling against Charles V through the Treaty of Chambord (January-February 1552), managed to capture the Three Bishoprics: Metz, Toul, and Verdun (1552), French-speaking territories. François de Guise, besieged at Metz (October 1552), brilliantly organized the defense and emerged victorious. However, though triumphant at Renty on August 13, 1554, the imperial forces were victorious in Italy the following year.

Exhausted by the war, the aging Charles V granted Henry II a five-year truce, the Truce of Vaucelles (February 1556), and soon after abdicated (September 1556). Besides retaining the Three Bishoprics, France was allowed to keep Piedmont. The truce, however, was short-lived, and war resumed in 1556, first at sea and then in Italy, where the French suffered a series of defeats.

Boulogne was nevertheless retaken by the French in 1556. The Duke of Savoy, Emmanuel-Philibert, a general in the service of the Empire, marched on Saint-Quentin. Montmorency was captured (August 1557), but Coligny cleverly took control of the city, holding the siege and stopping the Duke’s advance on Paris.

Henry II was defeated at Saint-Quentin (1557) by King Philip II of Spain. However, with the determination of François de Guise, who had just returned from Italy, Henry managed to recapture Calais (1558), which had been under English control for two centuries. Faced with financial difficulties and the Protestant issue, Henry II decided to end the Italian wars by signing the Peace of Cateau-Cambrésis (1559).

Through this treaty, France ceded Savoy, Bugey, Bresse, and Milan, but retained Pinerolo, the Marquisate of Saluzzo, Metz, Toul, Verdun, and Calais. Additionally, the treaty arranged the marriage of Henry II’s sister to the Duke of Savoy, and that of his daughter, Elizabeth, to Philip II, recently widowed of Mary Tudor.

The End of Henry II’s Reign

The king then had a free hand to combat the Protestants. A devout and uncompromising Catholic, Henry II had pursued them from the beginning of his reign. In December, the king decided that all books printed in France or abroad had to be submitted for approval by the faculty of theology. Protestants caught in the clandestine practice of their worship faced the death penalty. Despite this strictness, Calvinism spread across France, and many nobles converted. In June 1559, the Edict of Ecouen urged the courts to punish Protestants who appeared before them with death. The Wars of Religion would begin a year later.

Henry II was the last French monarch to participate in jousting tournaments. During the celebrations held for the marriage of his daughter, Elisabeth, the king was mortally wounded in a tournament organized near the Tournelles on June 30, 1559, after being struck in the eye by a lance blow delivered by Montgomery, captain of his Scottish guard.

After a long and painful agony, he died on July 10, 1559. Having had ten children with Catherine de’ Medici, he left the throne to his fifteen-year-old son, François II.

Two of his other sons would reign under the names of Charles IX and Henry III.

Like his father, Henry II was a fervent patron of the arts, and his court was one of the most splendid in Europe. Ronsard and the Pléiade celebrated his triumphs. His tomb, along with that of his wife, can be found today in Saint-Denis.