Henry III, King of France from 1574 to 1589, was the last ruler of the Valois dynasty. The fourth son of Henry II and Catherine de’ Medici, he was not initially destined to reign.

A skilled legislator, he exhibited a strong desire for national unity in a France then torn apart by the French Wars of Religion. Intelligent and cultured, this monarch left behind a mixed legacy, at times overshadowed by a “black legend” that includes homophobia and accusations of inconsistency, even tyranny. Beyond these perceptions, his political actions allowed his successor, Henry of Navarre, to end the civil war. Henry III was assassinated on August 1, 1589, by the fanatical Dominican monk Jacques Clément.

Key Achievements and Events

The Duke of Anjou: The Future Henry III

Born on September 19, 1551, Henry of France was the fourth son of King Henry II and Catherine de’ Medici. Initially, he was baptized with the name Alexandre-Édouard. The choice of the name Édouard was no accident and encapsulated the political and religious contradictions that troubled France at the time. He received the title of Duke of Anjou.

Édouard, an unusual name among the Valois, was a tribute to the child’s godfather, the adolescent King Edward VI of England, a country leaning towards Calvinist reform. Although King Henry II was at the forefront of Protestant repression, he still maintained a strong sense of political pragmatism. England could be a valuable ally in the struggle against the Habsburgs, and this gesture might also appeal to the increasingly influential Huguenot nobility.

Alexandre-Édouard, who became Henry in 1565, spent his childhood, like his siblings, away from his parents in Blois. Nevertheless, his mother, Catherine de’ Medici, a true Florentine, ensured that her son received a refined education typical of the Renaissance. His tutor (also the tutor of his elder brother, the future Charles IX) was Jacques Amyot. A true fountain of knowledge, Amyot, a Plutarch specialist, recognized in the young Valois the qualities that would make him a cultured and eloquent ruler: “one of the best speakers of his century.”

The young prince was quickly involved in royal power, attending his first Estates General at the age of seven (in 1560). As Catherine’s favorite child, an accomplished swordsman, and endowed with a striking presence, it was only natural that he was appointed Lieutenant General of the kingdom at the age of sixteen, thus beginning his political career.

In the Turmoil of the Wars of Religion

As the second most powerful military leader in France after his brother, King Charles IX, Henry made an enemy of the leader of the Protestant party, the formidable Prince of Condé, who coveted the same position. Their rift led to Condé’s departure from court and the start of the second war of religion in 1567.

Concerned with protecting royal authority, Henry proved himself a competent general, notably winning the Battle of Jarnac, which resulted in the tragic death of Prince of Condé. His rising influence began to overshadow King Charles IX, leading to discord between the brothers and pushing Henry towards the camp of the Duke of Guise (a family of Lorraine origin that was then essential), the champion of ultra-Catholicism.

While Charles advocated for reconciliation with the reformers (likely due to the influence of his Protestant friend Admiral de Coligny), Henry favored a firmer stance. In his mind, it was already clear that royal authority could not tolerate any dissidence, whether religious or otherwise.

Henry’s involvement in the St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre (the last days of August 1572) remains controversial. Caught between the extremism of the Catholic League and the Guise supporters, and his duty to maintain order (in a rebellious Paris overwhelmed by religious fanaticism), he was also preoccupied with more distant events. Henry was no longer content to be second in the kingdom, and a crown now seemed within his reach.

On July 7, 1572, Sigismund Augustus Jagiellon, King of Poland-Lithuania, died. The state he governed was quite unique within Christendom. This nobility-led republic, ethnically and religiously diverse, elected its kings. A significant portion of the Polish nobility was Protestant, and Henry sought to secure their support in the upcoming election.

Thus, it seems unlikely that he would have incited the populace to massacre the reformers on August 24, 1572. After further battles against the Protestant party (as the Wars of Religion resumed their bloody course), including a failed siege of La Rochelle, the prince, while in the midst of a romance with Marie de Clèves, was elected King of Poland. On August 19, 1573, a Polish delegation came to meet the future king and present him with the laws of his future realm.

Henry, who, like all Valois, was in favor of strong royal authority, had to adjust to the realities of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. The new king was thus forced to sign the Henrician Articles, a set of laws that required him to cease persecuting Protestants in France and to respect religious tolerance. Aware that his royal powers would be severely limited, Henry took his time departing for Krakow, only arriving in February 1574…

From King of Poland to King of France

The young king, well aware of the necessity of religious tolerance within his new states, could not tolerate the independence of the Diet and the nobility. He tried by all means to strengthen his authority, without fully succeeding, despite his deep involvement in his new duties. Henry had to admit that he “reigned but did not govern.”

On June 14, 1574, he learned of the death of his brother, Charles IX, of whom he was the heir. On the 18th, he secretly left Poland for the kingdom of France, where he intended to rule in the manner of his model: Francis I. After a dramatic escape (which would earn him a dark legend in Poland) and a journey filled with celebrations fit for his status, Henry arrived in France in September 1574.

He was crowned king on February 13, 1575, marrying two days later Louise de Vaudémont-Nomény, a beautiful princess from Lorraine, but most importantly, close to the Guise faction. Henry III knew the magnitude of the task ahead: restoring peace and harmony within the kingdom, a necessary prerequisite for consolidating royal power, meant he had to win the favor of both the ultra-Catholics and their Huguenot enemies.

Unfortunately for the king, his younger brother, the Duke of Alençon, tipped the balance in favor of the Protestant party when he allied with Henry of Navarre (the future Henry IV), who had entered armed rebellion. The resulting war turned into a disaster for the king, and he was forced by the Edict of Beaulieu (May 1576) to grant a very favorable peace to the Protestants. In response, the ultra-Catholic League emerged as a militant force.

With the Peace of Beaulieu, the king seemed worn out before he had even begun to reign. His brother, the guarantor of the alliance between moderate Catholics and Protestants, became the strongman of the kingdom, and the treasury was nearly empty. Nevertheless, Henry was not without options.

Capitalizing on the humiliation of the Catholics, the king positioned himself as their defender and protector, which allowed him to once again align with the Guises.

To obtain the financial means for his revenge, Henry convened the Estates General at Blois (1577), where he displayed great tactical skill. Faced with deputies who were already considering reforming the kingdom in a parliamentary direction, “When the Estates write, it is France itself that writes,” he exploited divisions and rivalries to bury any constitutional ambitions and reaffirmed himself as the undisputed leader of the Catholics. Despite his tenacity, he did not secure the financial resources he sought, a lesson his successors would remember in their relations with the parliamentarians.

Nevertheless, the war resumed shortly afterward (the sixth religious war, 1577), leading to a modest but real victory for the royal camp. The monarch had received support from his brother, who had temporarily shelved his ambitions.

With the Edict of Poitiers (1577), which ended the conflict, the Protestant camp was forced to make various concessions. It was time for Henry to consolidate his position through diplomacy. With the mediation of his ever-present mother Catherine, he initiated a rapprochement with Henry of Navarre while supporting his brother’s efforts in the Netherlands. These efforts had the advantage of uniting Catholics and Protestants in a common struggle against their hereditary enemy: the Habsburgs, something Henry IV would remember!

The War of the Three Henrys

1584: seven years of relative peace, seven years of consolidating royal authority, seven years of intense legislative work, and yet Henry knew his throne was in danger. After almost ten years of marriage to Louise of Lorraine, he still had no heir, and his brother, who had presented himself as a valuable successor, had died of tuberculosis.

The Valois dynasty seemed destined to extinguish. According to Salic Law, the crown would pass upon Henry III’s death to Henry of Navarre, the leader of the Protestant party. This was, of course, unacceptable to Catholic opinion, which exerted constant pressure on the king to appoint a Catholic successor. The city of Paris, entirely in the hands of the League, was dangerously restless.

The hour had come for the triumph of Duke Henry of Guise. Ultra-Catholic passions condemned Henry III to another war, as confirmed by the Treaty of Nemours (July 1585), where he committed to “driving the heretics out of the kingdom.”

This War of the Three Henrys (Henry III of Valois, Henry of Guise, and Henry of Navarre) involved three camps, not two. Although seemingly aligned with the ultra-Catholics, Henry III did not sever all ties with the Protestants. The king, eager to maintain the independence of his states, knew that the Duke of Guise was strongly supported by the Habsburgs. On the other hand, a total defeat of Navarre would overly benefit the ambitious Duke of Lorraine, whom the king did not like. Thus, Henry waged war with allies he despised (the Leaguers) against an enemy (Henry of Navarre) whom he respected.

The result was a confusing situation, with the king attempting to maintain a precarious balance between the belligerents. Any misstep could prove fatal.

Henry’s maneuvers eventually exasperated the Duke of Guise, who in May 1588 defied the king’s authority by entering Paris, where he was hailed by the Leaguers. Fearing a coup, the king sent his troops to Paris, sparking an insurrection, the famous Day of the Barricades on May 13, 1588.

Although he bought time by initiating negotiations with the Leaguers, the last of the Valois had made his decision. Henry of Guise had to disappear. Overwhelmed by the excesses of the Parisian Leaguers (whose practices and demands echoed those of Étienne Marcel’s supporters two centuries earlier), the duke posed a great danger to royal authority. Henry III feared above all that a victory for the League would bring an end to the centralizing efforts of France’s kings.

In 1588, Henry of Guise’s position weakened. With the reduction of generous Spanish subsidies (following, among other things, the defeat of the Invincible Armada), the duke lost his prestige. Fearing that the king might make peace with his rival, the King of Navarre, he resigned himself to negotiating with Henry III at the Estates General of Blois.

On December 23, 1588, during a royal council, the king ordered the assassination of the Duke of Guise by the “Forty-five,” his personal guard. This assassination ended the ambiguity of the royal position but also provoked the uprising of the League’s France. The king was condemned by the ultra-Catholics, who now called for the murder of the man they considered a “tyrant.”

Logically, Henry III saw no hope except in a complete reconciliation with Henry of Navarre, who emerged as his successor (under the tacit condition that he once again renounce Protestantism). The two Henrys would go on to besiege Paris together, which was controlled by the Leaguers, whose militias were equipped with Habsburg funds.

The king, stationed in Saint-Cloud, would not live to see the destruction of the League. On August 1, 1589, a fanatical monk named Jacques Clément, an agent of the Leaguers, assassinated Henry III with a knife. Thus ended the Valois dynasty…

Henry III: The Last of the Valois

As evidenced by his actions, Henry III always aimed to maintain and strengthen royal authority, despite an extremely unfavorable context. His complex personality and his shifts in stance (often dictated by circumstances) earned him an unenviable reputation. However, much of this reputation stems from the hateful propaganda spread during his time by his enemies.

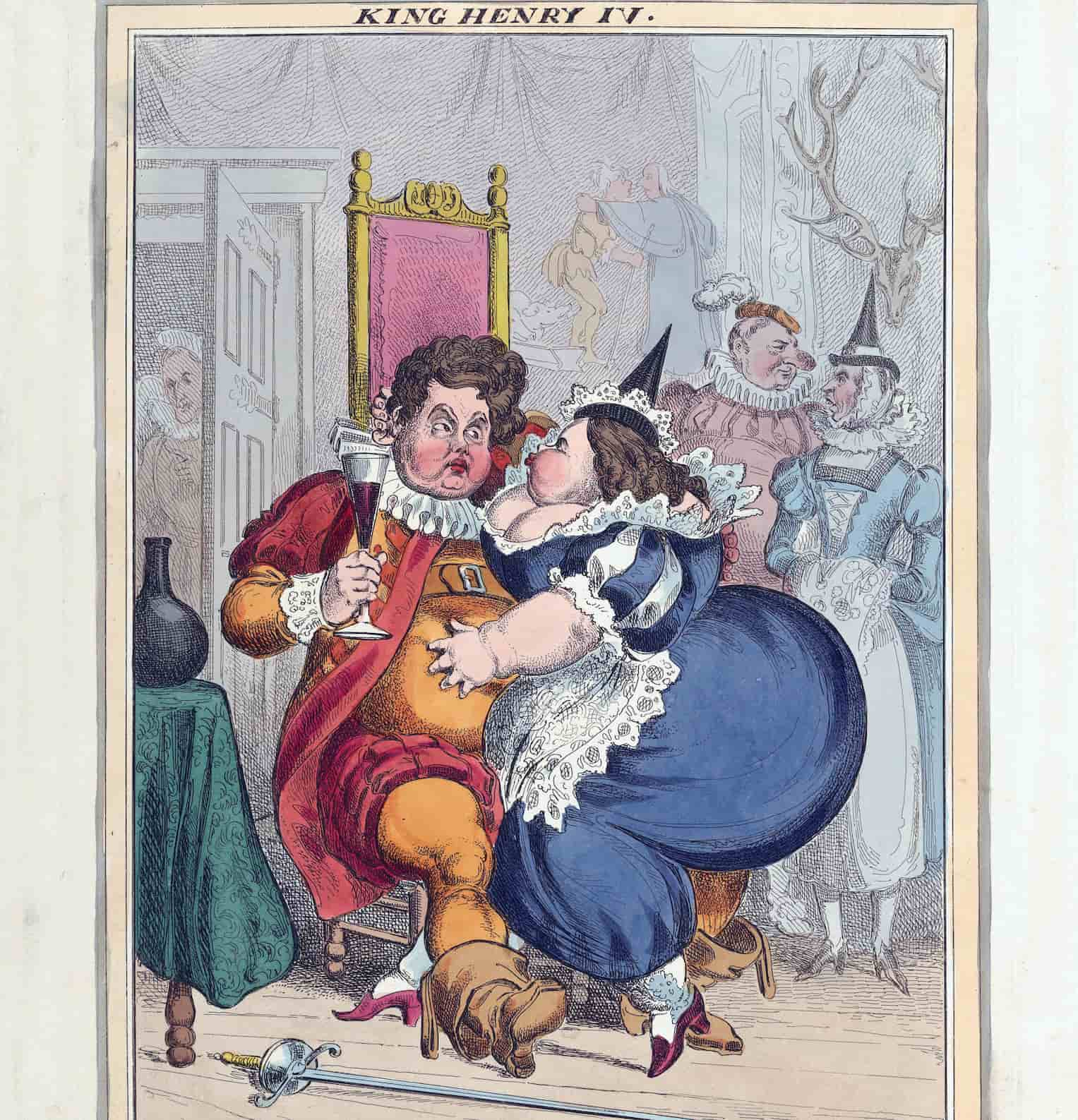

He was said to be weak. He did, indeed, yield many times to pressures from the nobles, but he never failed to regain control afterward. He was said to be cowardly and effeminate. Fond of beauty, often surrounded by elegant young men (the famous “mignons”), he was certainly not a rugged medieval sovereign thirsty for glory. Yet, this is to forget too quickly his warrior youth and personal courage, amply demonstrated at Jarnac and Moncontour. As for the rumors about his sexuality (the notorious “pink legend”), they hardly hold up in light of his numerous female conquests.

He was said to be frivolous and immoral. While he certainly never denied his extravagant taste for festivities and the arts, he was also a devout king, concerned for the salvation of his soul, with remarkable displays of faith.

King Henry III, despite the challenges he faced, managed to govern and left behind a significant legislative legacy (the Code Henri III). He had a lofty view of royal authority and a modern conception of the state. He avoided the collapse of the French monarchy, leaving it to his successors to once again elevate it to a great power.

Agrippa d’Aubigné summarized the feelings of many French people of the time regarding the king: “Thus ends Henry the Third, a prince of pleasant conversation with his own, a lover of letters, more generous than any king, courageous in youth and then desired by all; in old age loved by few, who had many qualities of a king, wished for the throne before he had it, and worthy of the kingdom if only he had not reigned…“