Throughout all ages, war has been a complex and costly endeavor. The outcome and characteristics of confrontations between organized groups of armed people to resolve issues of power, territory, and resources have always depended on the means and skills they possessed. As a result, technology development, social organization, and knowledge of the surrounding world have always gone hand in hand with war and directly influenced its nature.

- 18th–15th Centuries BC: Invention of the Chariot

- Armor Production

- 13th Century BC: Mastery of Iron

- 10th Century BC: Warriors Ride Horses

- 7th Century BC: The Art of Battle Formations

- 5th–6th Centuries AD: Invention of the Stirrup

- 12th–15th Centuries: Professionalization of Armies

- 14th Century: Use of Gunpowder and Improvement of Cannons

- 16th Century: Development of Handheld Firearms

- 17th Century: Invention of Drill

- Mid-19th Century: Industrialization of Warfare

- Second Half of the 19th Century: Use of Railways

- Early 20th Century: Invention of World Wars

18th–15th Centuries BC: Invention of the Chariot

Since the beginning of bronze smelting, the production of sturdy chariots made of wood and metal, which could be easily maneuvered in battle, was a significant technical achievement of its time and required large amounts of metal. Additionally, maintaining these combat units, complete with horses and two-person crews, was expensive.

For this reason, war during the Bronze Age was a luxury affordable only to prosperous centers of civilization, such as Egypt. Chariots played a crucial role in the rise and fall of early state entities in the Middle East; it was difficult to counter rapidly moving, fortified chariots from which streams of arrows rained down on enemies.

Interestingly, in the “Iliad,” which provides a detailed account of Bronze Age warfare, heroes use chariots not in battle but only to quickly reach the battlefield or return to camp. This is another indicator of the chariot’s significance. Even where, for some reason, chariots were not used to their full potential, they served as a recognized attribute of power and prestige. Kings and heroes went into battle on chariots.

Armor Production

In the same “Iliad,” the “helmet-flashing” heroes, clad in armor and armed with heavy spears with bronze tips, are the rulers of individual lands. Armor was so rare that the manufacture of some of them was attributed to the gods, and after killing an opponent, the victor would first try to seize the armor, a rare and unique item.

Hector, leading the Trojan army, after killing Patroclus, who wore Achilles’ armor, leaves the army in the middle of the battle and returns to Troy to don the unique armor. The rulers of the Mycenaean civilization, during whose era Homer’s events are set, largely ensured their power over their lands through possession of rare and expensive but extremely effective weapons and armor for their time.

13th Century BC: Mastery of Iron

The gradual spread of iron ore processing technology across the Near East and Southern Europe starting from around the 13th century BC led to iron competing with bronze as a relatively cheaper and much more abundant metal. It became possible to arm a much larger number of warriors with metal weapons and armor.

The reduction in the cost of warfare, combined with the use of metal weapons, led to significant changes in the “geopolitics” of the Ancient world: new tribes equipped with iron weapons crushed the aristocratic states of chariot owners and bronze armor wearers. Many states in the Middle East perished this way; Achaean Greece was conquered by Dorian tribes. Thus, the Kingdom of Israel rose to prominence, and simultaneously, the Assyrian Empire became the most powerful entity in the Near East during the early Iron Age.

10th Century BC: Warriors Ride Horses

Before the invention of harnesses and saddles, riding a horse or other hoofed animal was a precarious task requiring constant attention to balance, making the rider practically useless in combat. With the mastery of riding skills using harnesses, cavalry emerged as a type of military unit in Assyria in the 10th century BC and quickly spread thereafter. The primary beneficiaries of this new riding skill were Asian nomads, who previously bred horses for food. With the mastery of horseback riding, which allowed the use of weapons, particularly archery, they gained a new source of military power, enabling them to cover large distances at previously unattainable speeds.

From around the 8th century AD, a mechanism of confrontation developed between the nomadic “steppe” and sedentary agricultural societies. The successive nomads gained the ability to raid, collect tribute, or serve more advanced and wealthier agricultural communities, equipped with the resource of mounted troops. This mechanism remained virtually unchanged for many centuries—until the collapse of the Mongol Empire.

7th Century BC: The Art of Battle Formations

When it became possible to equip a large number of able-bodied men with armor and heavy weapons, there arose a special need to organize and manage such armed masses. It was during this time that specific types of battle formations, such as the Greek phalanx, emerged. This formation, consisting of dense ranks of heavily armed soldiers arranged in several rows, first appeared in Sparta in the 7th century BC.

Maintaining such a formation became a key to victory against armies lacking similar organization. Many military metaphors, such as “feeling the elbow,” are believed to originate from the phalanx formation (where a soldier indeed felt the elbows of his neighbors). The victories of Roman legions were also owed to a complex system of formations, allowing for maneuvers and reorganization during battle, and the solid training of fighters who understood the need to maintain formation.

5th–6th Centuries AD: Invention of the Stirrup

By standing in the stirrups, an archer became much more stable and could aim more accurately. Even greater changes were brought to cavalry combat techniques, which required contact with the enemy. The stirrup turned the rider and horse into a single mechanism, allowing the combined mass of the horseman and his mount to be transferred to the opponent along with a lance or sword strike, turning cavalry into the “living combat machines” of their time.

In Western Europe during the Middle Ages, this advantage was further developed by heavy cavalry, leading to the emergence of heavily armored knights. A knight, armored and sitting in stirrups, attacking with a heavy lance at full gallop, concentrated an unprecedented amount of power at the tip of the lance during the moment of attack. This led to a new aristocratization of war, as the wielders of such effective and expensive weapons were a narrow layer of feudal lords, shaping the nature of warfare in the Middle Ages.

12th–15th Centuries: Professionalization of Armies

The effectiveness of the crossbow as a ranged weapon so amazed medieval society that in 1139, the Second Lateran Council deemed it necessary to prohibit crossbows and bows in wars between Christians. This ban had little effect, especially in the case of the bow. The experience of the Hundred Years’ War between England and France—one of the pivotal medieval conflicts marking the crisis of the classical Middle Ages—showed that units of English archers recruited from peasants and armed with longbows could deal devastating blows to the flower of French knighthood in several key battles.

The confrontation among Italian cities, local feudal lords, and the Holy Roman Empire led to new forms of resistance against knightly forces: pike militias armed with long pikes, which, with organized cohesion and skillful use, could stop cavalry charges. The actions of these armed units (as well as crossbowmen and archers) required increasing coordination and mastery of complex weaponry, leading to the gradual professionalization of warfare—the emergence of mercenary units capable of offering their services, skilled use of weapons, and complex combat techniques. Warfare, especially in Italy, gradually became the domain of professional teams. Fierce competition led to the rise of the arms market: Italian cities offered increasingly advanced models of crossbows, armor, and various types of cold weapons, from which mercenary units could choose.

14th Century: Use of Gunpowder and Improvement of Cannons

It is believed that gunpowder was invented in China and used in warfare from the 12th century, but there it was initially used to launch giant arrows, as it was initially in Europe. However, from the 14th century, bronze cannons using gunpowder began launching stone cannonballs. Each of these cannons required tons of metal, and their production could only be afforded by monarchs. Later, with the invention of cast-iron cannonballs, the need for enormous cannons that launched stone projectiles was eliminated, as metal cannonballs had a more destructive effect with a smaller diameter.

With the invention of the wheeled carriage, allowing cannons to be transported to the required location, artillery became an almost unbeatable force, capable of destroying any stone fortifications within hours. In some sense, it became the “last argument of kings.” Possession of siege cannons was, in most cases, indeed the privilege of centralized monarchies capable of paying for their production and maintenance.

If the opponent lacked artillery, the outcome of the confrontation was almost predetermined. This factor played a significant role in the expansion of the Muscovite Tsardom to the east and south under Ivan the Terrible; cannons were equally significant during the era of the Great Geographical Discoveries and the establishment of European dominance in various world regions.

16th Century: Development of Handheld Firearms

Portable firearms that could be used by infantry revolutionized the combat capabilities of foot soldiers and changed the nature of warfare. However, the firearms of that era were still quite heavy and required time to load and use. Effective use in battle demanded the development of specific methods for coordinating with other units.

One successful experiment was the formation of the Spanish tercios—a square formation of pikemen that protected musketeers positioned in the center. This tactic turned the Spanish infantry into one of the most formidable forces on the European battlefield for most of the 16th century.

17th Century: Invention of Drill

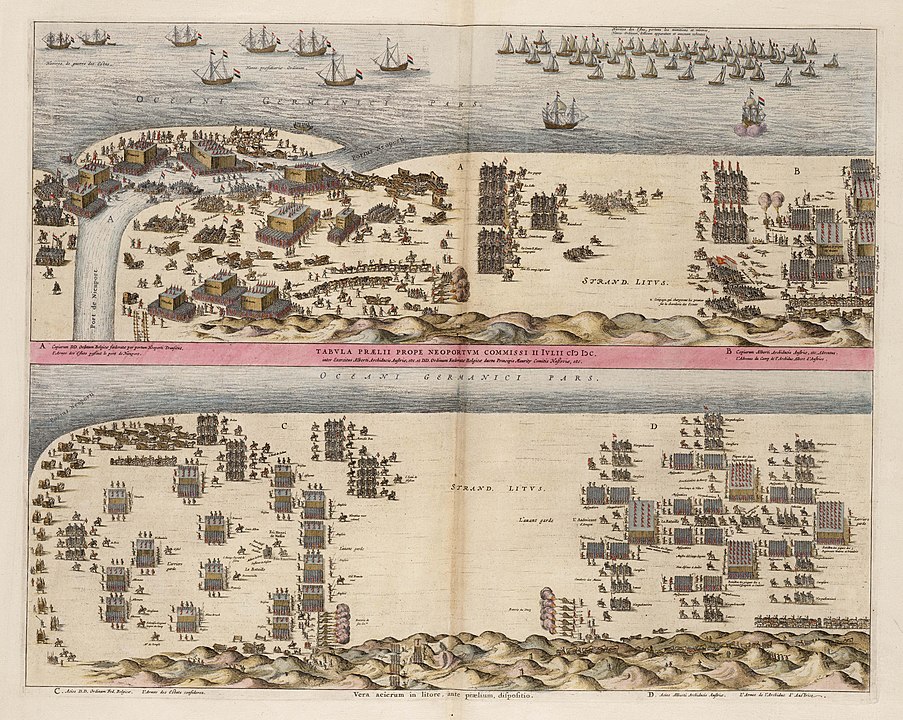

One of the most significant innovations in army management, shaping it into the form we recognize today, came from Maurice of Orange, the ruler of the Netherlands from 1585 to 1625. He was the first to approach military operations as a series of fundamental maneuvers that soldiers must perform. His innovations resulted in the division of the army into smaller units, such as companies and platoons. Each unit had to precisely execute commands for formation and regularly conduct drills on marching and weapon handling—essentially inventing the military drill.

Soldiers were required to master the movements involved in maneuvering their units, which could be employed in battle. Similarly, Maurice of Orange meticulously developed and clearly described methods of handling the musket, focusing on practicality and efficiency. These innovations created a unique military mechanism.

Soldiers integrated into this mechanism performed any command with precision and without error, and their automatic movements allowed them to maintain formations even under enemy fire. Like any automation with a well-developed protocol of actions, this led to a shift in the perception of military service. Essentially, Maurice’s system implied that any “human material” could be transformed into a soldier through rigorous drill.

In the second half of the 17th century, Maurice’s book reached Russia, where it sparked the formation of regiments organized in the foreign style and later influenced Peter the Great’s military reforms. The ideal of an army where a soldier is primarily an instrument for executing a commander’s precise orders effectively lasted until the end of the 18th century.

Mid-19th Century: Industrialization of Warfare

The French Revolution brought forth mass armies recruited through national conscription. However, these armies, despite changes in management methods and tactics, were still equipped with weapons that had remained nearly unchanged since the 17th century (excluding advancements in artillery, whose range and accuracy had significantly improved during the revolutionary and Napoleonic wars). The fact that Napoleon Bonaparte was ultimately defeated by a coalition of conservative European powers temporarily halted major changes in the armed forces.

A new impetus for progress was the spread of rifled muskets. Their mass use by the French and British forces who landed in Crimea in 1854 against the mostly smoothbore musket-armed Russian army provided the anti-Russian coalition with victories in open battles and forced the Russians to retreat to Sevastopol. The Crimean War, where the slight lag of Russian armed forces in adopting newly emerging inventions—such as steam fleets or rifled muskets—became a critical factor, effectively accelerated the arms race.

One of the stages of this race was the rearming of armies with new rifled breechloader muskets. It was during this time that firearms were first produced not by hand but on new milling machines invented in the United States, which manufactured identical parts. In essence, only after this did firearms become industrialized; previously, gunsmiths made each musket by hand, fitting each component individually.

When Colonel Samuel Colt first demonstrated the advantages of machine-manufactured revolvers at the 1851 Great Exhibition in London by disassembling several revolvers, mixing their parts, and then reassembling them, it caused a sensation.

Artillery advanced similarly. The development of the steel industry allowed the creation of new breech-loading cannons, which demonstrated new destructive capabilities. The fundamental design of artillery pieces, developed in the 1860s–1870s, remains largely unchanged to this day.

Second Half of the 19th Century: Use of Railways

Mass armies (often formed by conscription) became a reality of new wars, armed with new types of weapons. The rapid movement and supply of such large forces using traditional horse-drawn transport became an impossible task. Although the first railways began to be built in Europe in the 1830s, their use in war pertains to a later period. One of the first wars where the construction of a railway played a crucial role in its outcome was the Crimean War. The 23-kilometer railway built between the Balaklava base of Anglo-French troops in Crimea and their combat positions in front of besieged Sevastopol solved the problem of supplying the invaders’ positions with ammunition.

The rapid delivery of supplies and equally swift deployment of large troop contingents transformed perceptions of the speed of army mobilization. Now, within a few weeks, a country with a railway network could switch to a war footing and deploy an army with the necessary resources to the desired front. Europe literally entered World War I on railways that transported troop trains to the borders of the warring states, according to carefully developed mobilization plans.

Early 20th Century: Invention of World Wars

The acceleration of technological progress brought new discoveries and inventions into the service of war. Internal combustion engine vehicles, aviation, poisonous gases, and barbed wire—all found military applications during World War I and clearly indicated that future wars would bear little resemblance to the technological understanding of warfare in previous eras.

During World War II, all these technologies were further developed and refined, becoming even more lethal. The mastery of radar, rocket technology, the first steps in computing, and the advent of nuclear weapons made wars even more complex and brutal. It is still challenging to judge how the latest technological inventions, such as precision weapons, information systems capable of processing vast amounts of data, unmanned aerial vehicles, and other significant technological innovations, will affect warfare.

It is possible that the changes of recent decades will again turn warfare conducted by technologically advanced nations into the domain of specialists requiring thorough preparation while simultaneously making the weapons used in wars and victories extremely expensive—even for wealthy states.