Before the Common Era

Traces of Cancer in the Remains of Ancient People

In 1990, during excavations of the Chiribaya tribe cemetery in Peru on the northern border of the Atacama Desert, American professor Arthur Aufderheide discovered the mummy of a young woman with osteosarcoma — a malignant bone tumor. These remains were well-preserved thanks to the local climate: clay extracted all the liquid from the body, and the desert wind dried the tissues. However, scientists do not always find remains of tumor tissues. Sometimes, they come across traces of the disease left in the body of an ancient person, such as small holes in the skull and shoulder bones — results of metastases from skin melanoma or breast cancer.

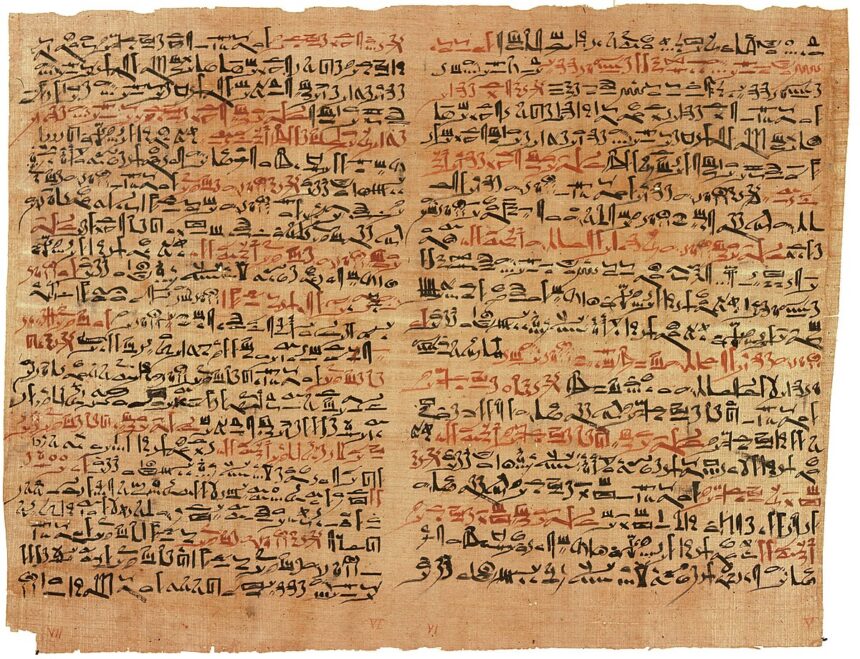

Incurable “Lumps in the Breast” from the Edwin Smith Papyrus

One of the earliest written records of the disease is the Edwin Smith Papyrus, named after the American archaeologist who bought the artifact in an Egyptian market in 1862. This ancient Egyptian manuscript, dated to around 1600 BCE, is likely an incomplete copy of an earlier medical treatise created in the 27th century BCE. Its authorship is attributed to the famous Imhotep — an architect and healer of the Old Kingdom period. The surviving document describes 48 cases of various injuries, with the forty-fifth section unexpectedly devoted to the consequences of a severe specific disease — presumably breast cancer:

When you examine the swelling lumps in the breast and find that they have spread throughout the breast, and if you place your hands on the breast, you find no heat and the tissues feel cool, with no graininess, internal fluid, or liquid discharge, but they protrude when touched, then you can say of the patient: ‘Now I treat the growth of tissues… the enlarged lumps of the breast mean the presence of swellings in the breast, large, spreading, and firm, and touching them is like feeling a ball of bandages, or they may be compared to an unripe fruit, hard and cool to the touch…’.

For each injury described in the papyrus, the author suggests different treatments: for example, poultices for wounds and balms for burns. However, the mysterious “swelling lumps in the breast” baffled the ancient physician — unable to find a cure for this ailment, the “Treatment” section dryly states: “None exists.”

The Persian Queen Atossa and the Successful Surgical Treatment of Breast Cancer from Herodotus’ “Histories”

Two millennia after the Imhotep Papyrus, a similar disease reappears in written sources. Herodotus, in his “Histories,” tells of the Persian queen Atossa, who suffered from a bleeding breast tumor. Some researchers believe she had inflammatory breast cancer. None of the remedies helped Atossa, so the Greek physician Democedes proposed surgically removing the malignant tumor. The queen agreed, and the operation ultimately saved her life. Thus, Atossa’s story can be considered the first recorded example of a successful mastectomy — a surgical procedure to remove the breast.

Ancient Rome

Black Bile

Roman physician Galen, who lived from 129 to 216 CE, following Hippocrates, believed that a healthy person’s body was in balance with four humors (fluids): blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile. An excess of any humor inevitably led to illness, and treatment involved removing excess fluid from the body, for example, through bloodletting, emetics, and laxatives.

Galen believed that malignant tumors were caused by an excess of black bile, which became a dense mass in the body. Interestingly, medieval physicians believed that an excess of black bile also caused melancholy: μελαγχολία in ancient Greek means “black bile.” Galen, whose authority remained unchallenged for over a thousand years, argued that the disease could not be defeated by surgery: the black bile would remain and pose a threat of new tumors. According to him, a patient could only be supported with general therapeutic measures.

Middle Ages

Boar Tusk, Fox Lungs, and Ground Elephant Bone

Galen’s views predetermined the medieval medical approach to tumors. Surgery was generally considered more harmful than beneficial, and the absence of radical treatment was seen as the best possible remedy. An alternative to the surgeon’s knife was a wide range of rather exotic remedies: arsenic tincture, lead tincture, boar tusk, fox lungs, ground elephant bone, crushed white coral, castor bean seeds, senna plant, and more. Alcohol and opium tincture were used to relieve unbearable pain.

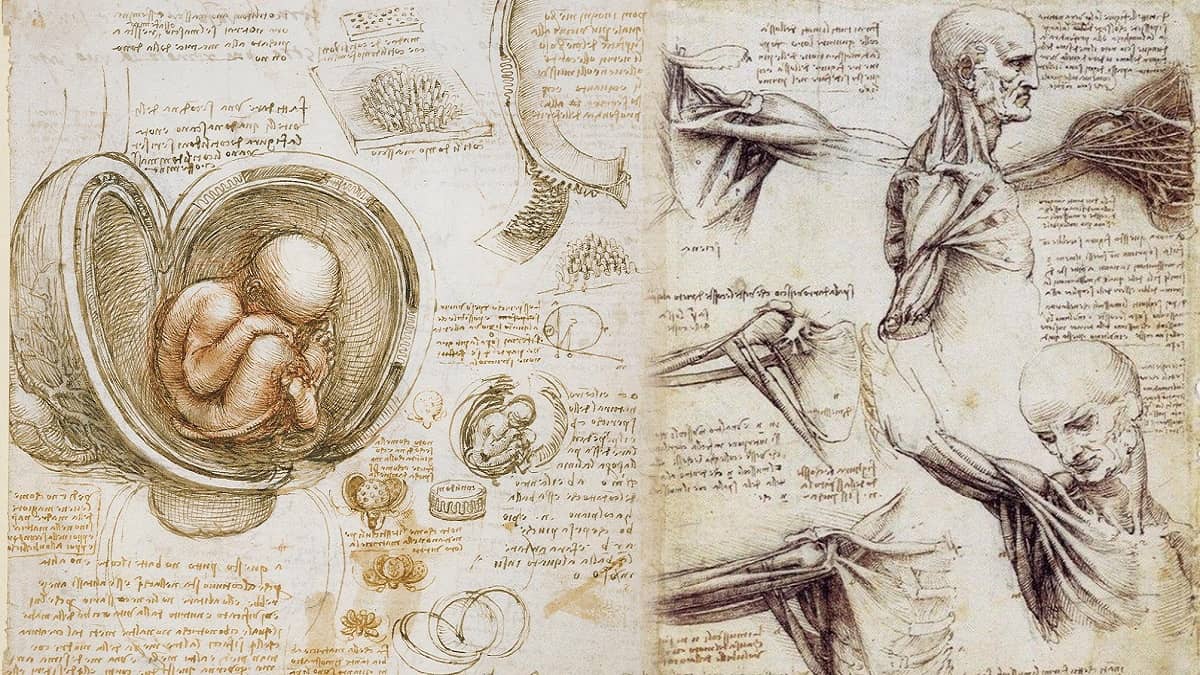

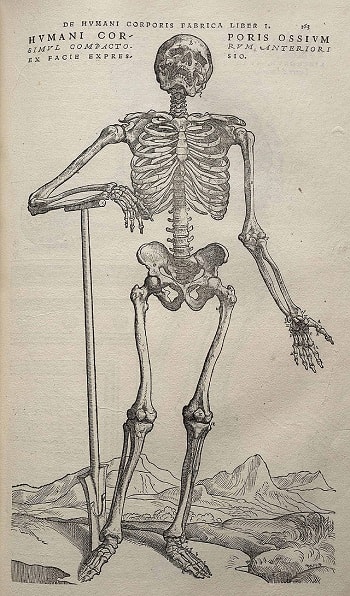

In the Renaissance, medicine revisited Galen’s idea that an excess of black bile in the body caused malignant tumors. Andreas Vesalius, the founder of scientific anatomy and author of “On the Fabric of the Human Body in Seven Books” (1543), who personally dissected corpses, could not find even the slightest trace of the infamous substance supposedly responsible for the development of tumors.

Enlightenment: Cancer from an Excess of Lymph

Another suspected cause of malignant tumors was lymph (also known as phlegm in humoral theory). According to this new understanding, tumors were no longer attributed to mysterious black bile but to a clear fluid that permeates the human body and is responsible for a calm temperament. German physicians of the 17th–18th centuries, Georg Ernst Stahl and Friedrich Hoffmann, suggested that tumors consisted of fermented lymph, which could have different densities, acidities, and alkalinities in each specific case.

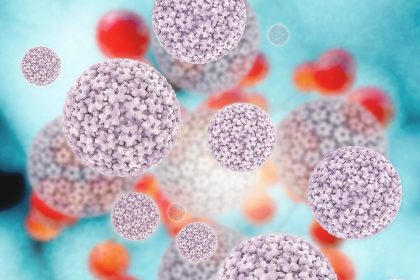

Cancer as Contagion

While Hippocrates, Galen, Stahl, and Hoffmann sought the cause of the disease within the body, two 17th-century Dutch physicians, Zacutus Lusitanus and Nicolaas Tulp, found it outside. Independently, they reached the same conclusion: cancer is contagious. The doctors proposed moving all patients outside major cities to isolate them and thus prevent the spread of the dangerous disease. The idea of the contagiousness of cancer, prevalent in Europe during the 17th and 18th centuries, is now considered mistaken. However, it is known that certain viruses, bacteria, and parasites can indeed increase the risk of developing tumors, such as the human papillomavirus or the bacterium Helicobacter pylori.

Cancer from Lifestyle

In the 18th century, scientists made three important discoveries that laid the foundation for the epidemiology of cancer. In 1713, Italian physician Bernardino Ramazzini noted that cervical cancer was almost nonexistent among nuns, while the incidence of breast cancer was relatively high. Ramazzini concluded that lifestyle (in the case of nuns — lack of sexual relations) could directly influence the development of this disease in women.

In 1775, English surgeon Percivall Pott discovered that scrotal cancer, often found in chimney sweeps, had an occupational nature: tumors arose due to the accumulation of soot in the folds of the scrotum. Pott’s discovery later led to the study of carcinogens associated with specific professions and the gradual adoption of occupational health and safety measures.

By the 20th century, it was established that carcinogens could include benzene, used in the production of medicines, plastics, and rubber, as well as the fine-fiber mineral asbestos, used in construction, among others.

It also became clear in the 18th century that bad habits could cause this disease. In 1761, English scientist John Hill, in his book “Cautions against the Immoderate Use of Snuff…,” first directly linked tobacco use and the development of tumors. However, lung cancer caused by smoking only became a subject of intensive research in the 20th century.

Surgery as the Only Way to Defeat Cancer

The medicine of the Enlightenment era drew a final line under Galen’s teachings. While Vesalius created a scheme of the “healthy” human body, the English anatomist Matthew Baillie managed to describe the “pathological” body in minute detail. In his work “The Morbid Anatomy of Some of the Most Important Parts of the Human Body” (1793), Baillie thoroughly examined various malignant formations, but in none of them could he find any hint of black bile.

Having “buried” black bile as a scientific error, medicine paved the way for surgery as possibly the only effective method of fighting malignant tumors. However, as before, patients could only rely on the skill of doctors. Indeed, in the absence of means to alleviate their condition during operations, it was difficult to count on a favorable outcome: people who agreed to go under the surgeon’s knife typically died from pain shock, heavy blood loss, and various infections.

19th Century

Ether and Carbolic Acid

The situation changed dramatically in the middle to late 19th century with the invention of anesthesia and antiseptics. American dentist William Morton began using the organic substance ether as a general anesthetic, while English surgeon Joseph Lister started using carbolic acid to disinfect wounds. After these important discoveries, doctors were able to resort to radical surgery when it was necessary to remove a tumor along with lymph nodes.

Surgeons such as Theodor Billroth and William Stewart Halsted became famous in this field. Billroth performed the first esophagectomy (removal of part of the esophagus), laryngectomy (removal of the larynx), and gastrectomy (removal of the stomach) in history, while Halsted performed radical mastectomy, which is the complete removal of breast tissue.

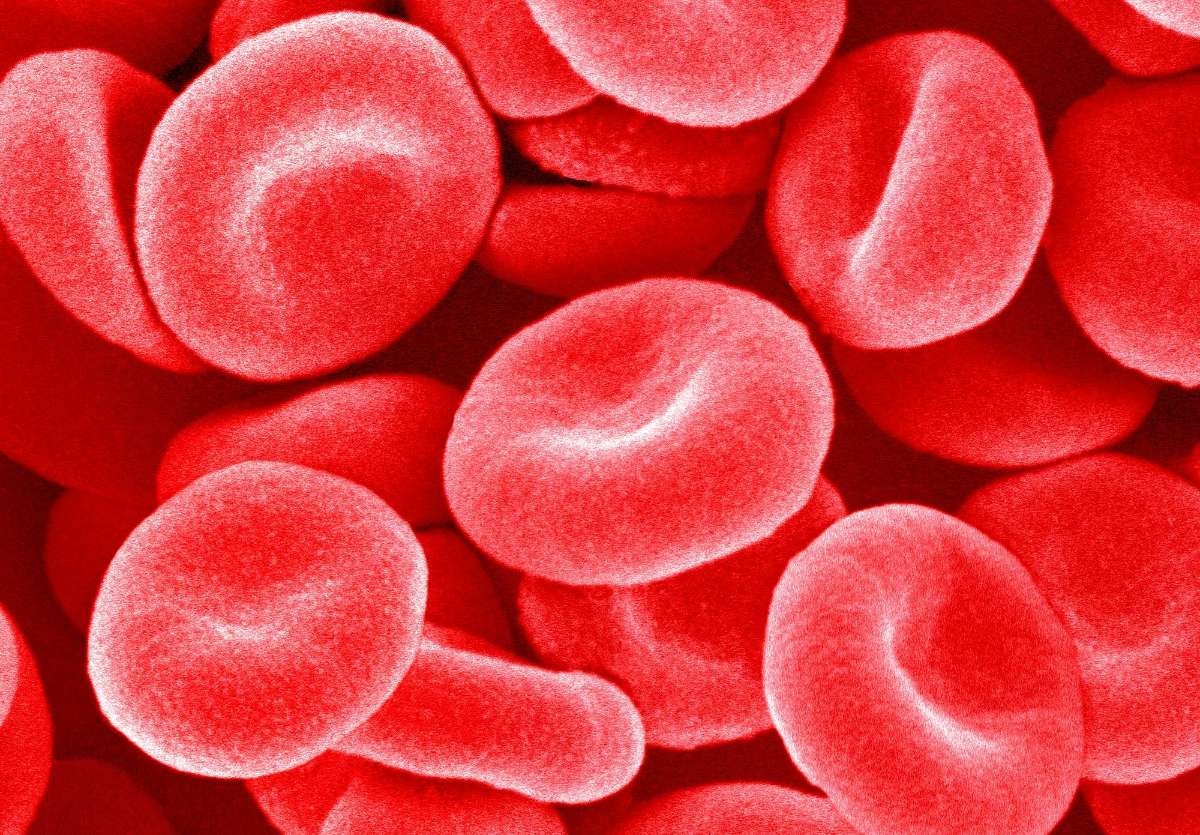

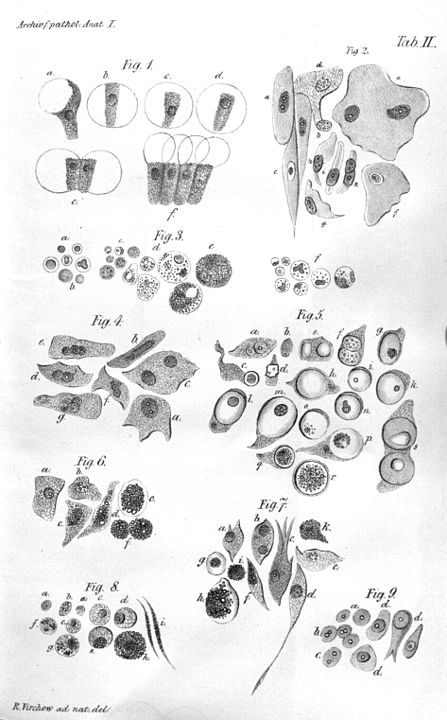

Cell Theory

In the 19th century, as microscope design was improved, scientists began to gradually approach an understanding of the true nature of cancer. In 1838, German biologist Johannes Peter Müller, in his work “On the Finer Structure and Form of Morbid Tumors,” proved that malignant formations consist not of lymph but of cells. However, he still believed that tumor cells were formed not from normal cells but from blastema between them. But his student Rudolf Virchow proved that all cells, including tumor cells, are formed from other similar cells: omnis cellula e cellula (“all cells come from cells”).

However, even Virchow was mistaken: he was sure that cancer spread through the body like a fluid. In the 1860s, German surgeon Karl Thiersch disproved Virchow, proving that tumors consist of epithelial tissue, not connective tissue. He showed that metastases appear as a result of the spread of malignant cells, not through some unknown fluid.

20th Century

Hormone Therapy

In the late 1870s, English physician George Thomas Beatson discovered a direct connection between the ovaries and milk production in the breast: after removing this organ in rabbits, he noticed that they stopped producing milk. This discovery led Beatson to wonder: could oophorectomy, or removal of the ovaries, have a positive effect on advanced breast cancer? Indeed, his experiments showed that such an operation often helped improve the condition of women with this type of cancer.

The scientist also suggested that the ovaries themselves might be the main cause of breast cancer development. Even before estrogen was discovered, Beatson determined that the female hormone from the ovaries had a stimulating effect on breast cancer. Beatson’s discoveries laid the foundation for modern hormone therapy, where substances like tamoxifen, which suppresses the effects of estrogen, and aromatase inhibitors, which inhibit enzymes that convert male hormones (androgens) into female hormones (estrogens), are used to treat and prevent breast cancer.

In the 20th century, a hormonal method was also found to treat a male disease—prostate cancer. In the 1940s, American scientist Charles Huggins discovered that after castration, patients experienced a sharp regression of metastatic prostate cancer. In addition, it was found that simultaneously decreasing testosterone levels and increasing estrogen levels helps in treating “male” cancer.

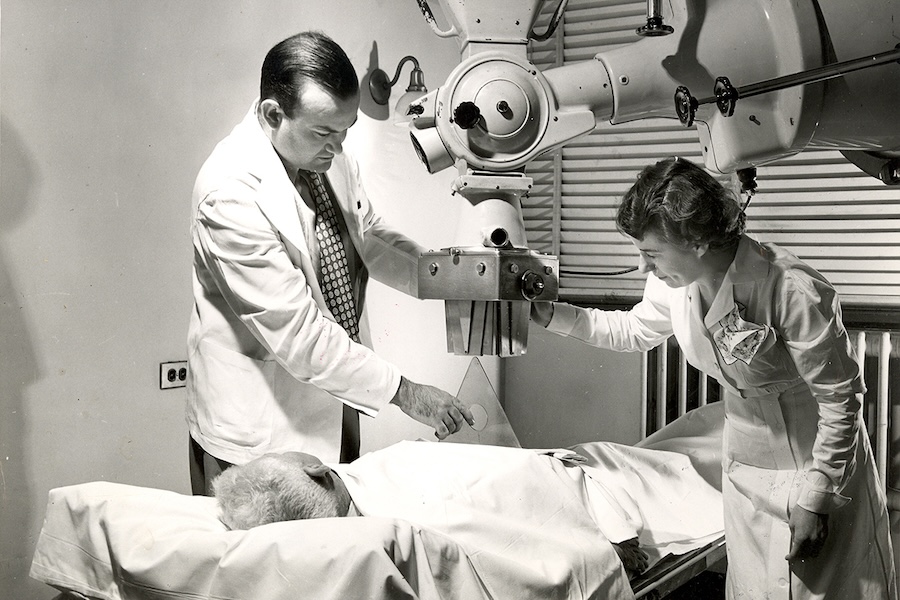

Radiation Therapy

At the end of the 19th century, Wilhelm Röntgen discovered X-rays, and Marie Curie and Pierre Curie discovered radium. Along with this came a new direction in tumor treatment: radiation therapy. Scientists found that radium could damage tumor cells in the body to the point of their complete destruction. However, in the early stages of radiation therapy, many doctors did not fully realize that radiation attacks healthy cells just as successfully as diseased ones. If the necessary dose is miscalculated, the rays can be deadly.

It took almost a century to fully control unmanageable radiation. At the end of the 20th century, conformal radiation therapy was invented, in which the beam is precisely directed at tumor tissues thanks to detailed three-dimensional models created using computed tomography.

Chemotherapy

The militarism of World War II killed millions of human lives but unexpectedly helped find a new means in the fight against malignant tumors. In the 1940s, as part of developing more effective weapons, American scientists Louis Goodman and Alfred Gilman, commissioned by the US Department of Defense, studied chemical substances related to mustard gas, a poisonous chemical compound. During these studies, they accidentally found that nitrogen mustard helps in treating cancer of the lymph nodes (lymphoma). This was one of the first steps towards introducing chemotherapy into medical practice.

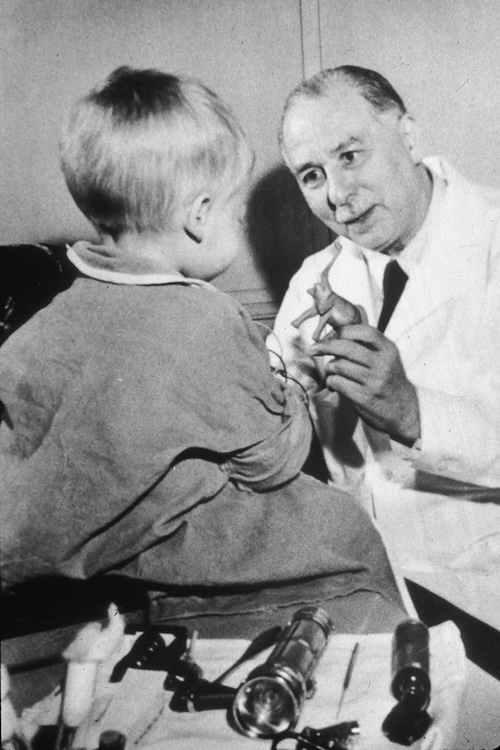

The real era of chemotherapy began with Sidney Farber, an American oncologist who, in the late 1940s, proved that a substance called aminopterin could cause remission in children suffering from acute leukemia: it blocks the division of leukocytes. Subsequently, adjuvant therapy became widely used in medical practice, which is a special chemotherapy aimed at destroying all tumor cells remaining in the body after surgery. Such therapy was first tested in the treatment of breast cancer, then in the treatment of colon cancer, testicular cancer, and other diseases. Another important innovation was combination chemotherapy, in which several different drugs are used simultaneously for more effective treatment.

Immunotherapy and Targeted Drugs

One of the most effective modern means in the fight against malignant tumors is immunotherapy. It has been actively used since the 1970s. Immunotherapy involves introducing special biological agents into the patient’s body that can both mimic the natural immune response and help the body’s own immune cells fight the tumor. The first targeted drugs—rituximab and trastuzumab—were created in the late 1990s; since then, they have been used to treat lymphoma and breast cancer, respectively.

A promising direction in modern immunotherapy is the development of special cancer vaccines. For example, in 2010, the first vaccine was approved in the USA for a form of prostate cancer that no longer responds to hormone treatment. This drug, unfortunately, cannot kill the disease, but it helps the immune system fight tumor cells, prolonging the life of patients who seem to have a fatal diagnosis.

Another important direction in modern immuno-oncology is the development of checkpoint inhibitors that regulate mechanisms that block the body’s immune response. The first of these drugs, ipilimumab, was approved in the USA in 2011. Now patients with diseases that were previously considered incurable have a chance for effective therapy. For example, former US President Jimmy Carter was able to get rid of metastatic melanoma when he was already over 90 years old.

Also, quite recently, cell therapy using lymphocytes taken from the patient, which are then genetically modified, began to spread. It was first and successfully used against acute lymphoblastic leukemia in a five-year-old American girl, Emily Whitehead. In addition, research in the field of gene therapy continues. In general, modern medicine strives for ever-greater personalization of treatment, which makes it possible to completely cure the disease.