The concept of a universal calculator, which originated in Britain in the 19th century with Charles Babbage and was developed by Alan M. Turing in the early 20th century, lies at the heart of the first computer’s creation. The development of advanced technology, especially in electronics, paved the way for the creation of the world’s first real computer, the ENIAC, in 1946.

Who invented the first computer?

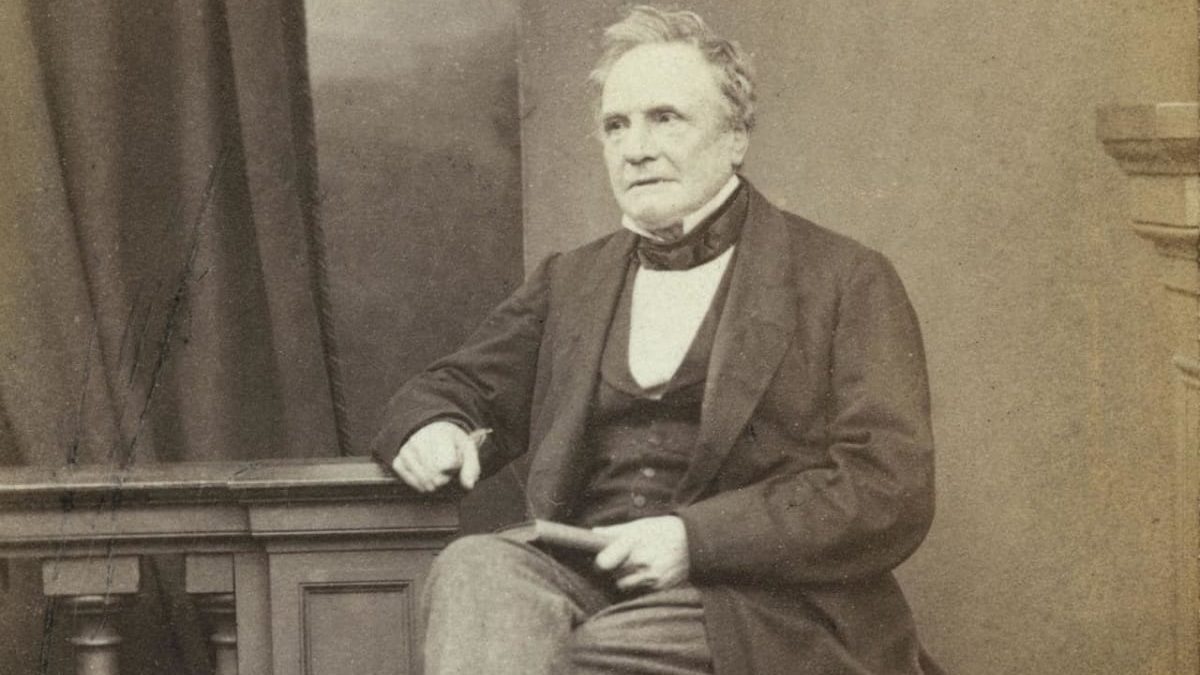

Charles Babbage, an English mathematician, developed the ideas for the first programmed calculating machine between 1834 and 1837. Using Blaise Pascal‘s work as a starting point, this visionary innovator developed the concept of programming using punch cards, which was already in use in the automated creation of music (the Barrel Organ), among other things.

This was the first step toward the development of modern computers. Regrettably, he was unable to realize his vision; the primitive state of technology at the time ensured that his “difference engine” was never produced.

After waiting almost a century, another English mathematician by the name of Alan Turing made a monumental breakthrough in the development of computer technology. In 1936, he wrote, “On computable numbers, with an application to the Entscheidungsproblem” which paved the way for the development of “Turing machines” that unified computation, programming, and computation languages.

Programmable calculators

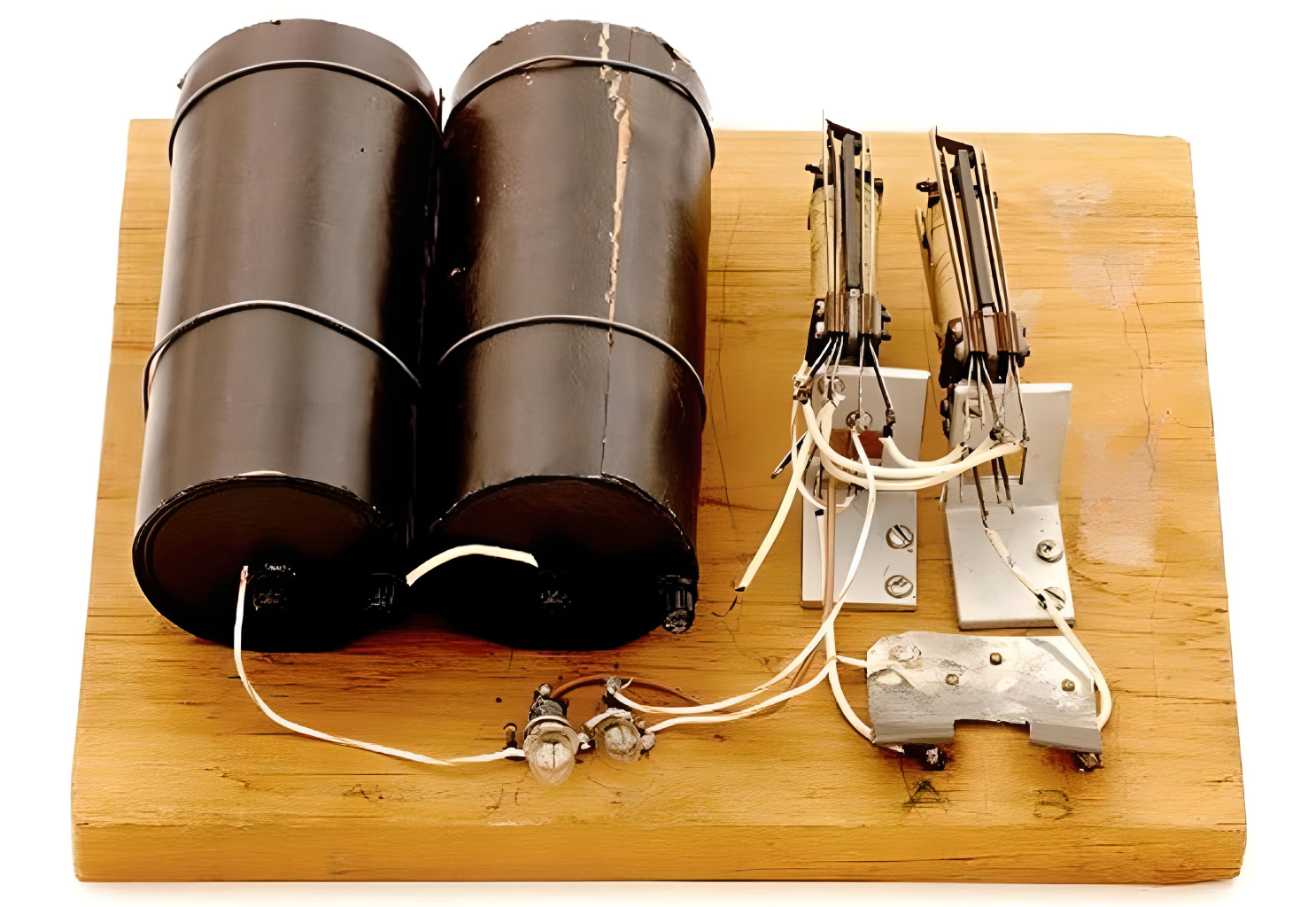

Major advancements were achieved during World War II, which owes a great deal to the contemporary age of computers. That’s why we ditched making mechanical parts and transitioned to digital computation and electronic circuits, including vacuum tubes, capacitors, and relays. This period saw the creation of the very first generation of computers.

Many programmable calculators appeared between 1937 and 1944:

- The “Model K“, developed in a kitchen, 1937.

- The “Z-series” computer, 1936.

- The Atanasoff-Berry computer, or ABC for short, 1942.

- The Complex Number Calculator (CNC), 1939.

- The Harvard Mark I computer, 1944.

The “Bombe” vs. “Enigma”

The United Kingdom put forth a significant effort at Bletchley Park during World War II in order to crack the German military’s encrypted communications. Bombes, machines developed by the Polish secret agency and perfected by the British, were used to crack the primary German encryption system, Enigma.

In 1936, Alan Mathison Turing (1912–1954) published “On computable numbers, with an application to the Entscheidungsproblem,” which paved the ground for the development of the programmable computer. He explained his own idea of the computer, which he called “Turing,” the first universal programmable computer, and, by extension, he created the ideas of “program” and “programming.”

Encryption keys, or ciphers, were discovered using these devices. The Germans developed yet another family of ciphers that were radically different from Enigma; the British dubbed them FISH. Professor Max Newman devised the Colossus, often known as the “Turing bombe,” to crack these systems. It was developed by engineer Tommy Flowers in 1943. The Colossus was later disassembled and buried due to its strategic value.

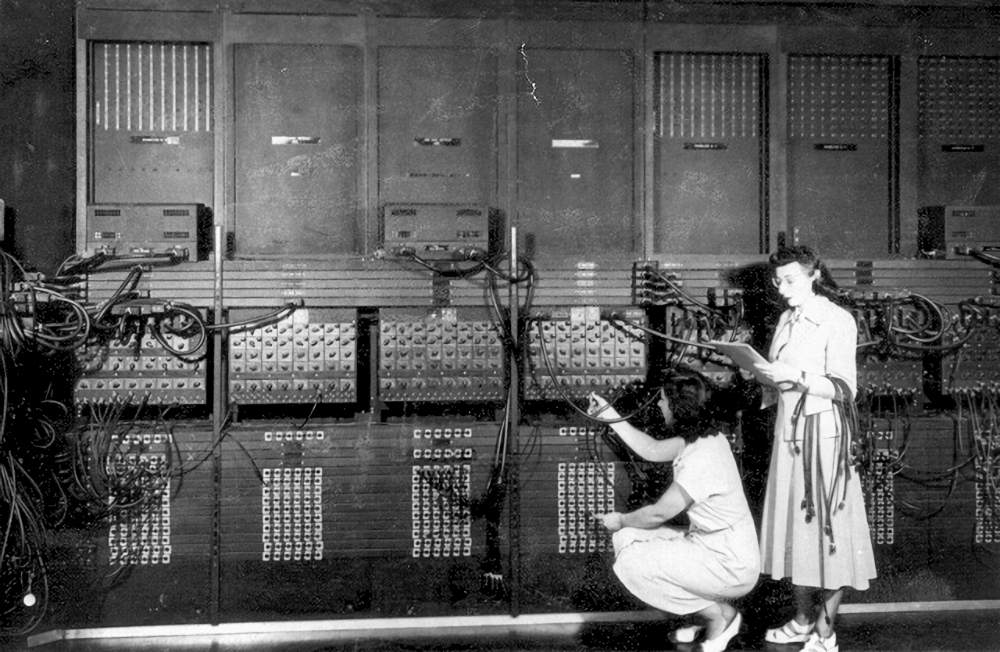

Colossus was not programmable as it was pre-programmed for a certain task. ENIAC, on the other hand, could be reprogrammed, albeit doing so could take many days. In this sense, ENIAC was the first programmable computer in history.

From ENIAC to modern computer

The first completely electronic and programmable modern computer to be Turing-complete did not exist until 1946. This was with the ENIAC (Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer) constructed by Presper Eckert and John William Mauchly.

In 1948, von Neumann architecture computers began appearing. These computers were distinct from their predecessors in that the programs were kept in the same memory as the data. This design allowed the programs to be manipulated just like data. It was pioneered in 1948 by the University of Manchester’s Small-Scale Experimental Machine (SSEM).

Afterward, IBM released its 701 models in 1952, and subsequent years saw the introduction of the so-called second-generation (1956), third-generation (1963), and fourth-generation (1971) computers, each of which saw the development of the microprocessor and continued the relentless pursuit of miniaturization and computing power.

The innovation of microprocessors, the newest incarnation of which is artificial intelligence, has made desktop computers, laptops, and several high-tech variants (graphics cards, cellphones, touch tablets, etc.) commonplace in our lives today.