History of delivering a message is creative and interesting. These days, when you need to get a message through to someone who is farther away, you pull out your phone and type away. We are used to receiving news from all around the globe through various media outlets. It’s practically impossible for a communication to be lost in transit nowadays, regardless of how far it needs to go or whether there are obstacles such as bad weather.

Delivering a message by courier

The origin of the modern marathon can be traced back to the story of the messenger Pheidippides, who ran 25 miles to carry news of the Persian defeat to Athens.

Previously, communications were sent using messengers. The most well-known is that Athens learned of the triumph of its army against the Persians at the Battle of Marathon (490 BC) through a messenger who sprinted the roughly 25-mile (40 km) trip from Marathon to Athens to herald the magnificent victory of Miltiades and then slumped dead upon reaching his destination.

Hills and other impediments littered the route, leaving Pheidippides tired and his feet bleeding by the time he finally made it to Athens.

Phryctoria

The ancient Greeks invented a semaphore system called Phryctoria. The towers were called “phryctoriae” and they were constructed on certain mountains such that each tower could be seen from the next. These beacon towers were usually located 20 miles away from each other. The towers were used to broadcast messages. During the night, large flames were lighted on mountains to send messages.

In his play “Agamemnon,” Aeschylus (525–456 BC) describes the use of “phryctoria” to convey the fall of Troy to the people of Mycenae. Long distance messages were sent by lighting massive flames atop distant mountains at night. The idiom “the news spread like wildfire” most likely refers to this or a related method of spreading information.

Heliograph

Another earlier method of message delivery, “heliograph,” may also be traced back to the ancient Greeks. In combat, bursts of light were created by combining sunlight with polished shields to serve as signals.

In the future, Emperor Tiberius utilized heliographs to issue daily commands from his residence on Capri to the mainland, which were subsequently broadcast to Rome.

Heliography comes from “helios,” meaning “sun” in Greek, and “graphein”, “writing.”

Chappe’s semaphore telegraph

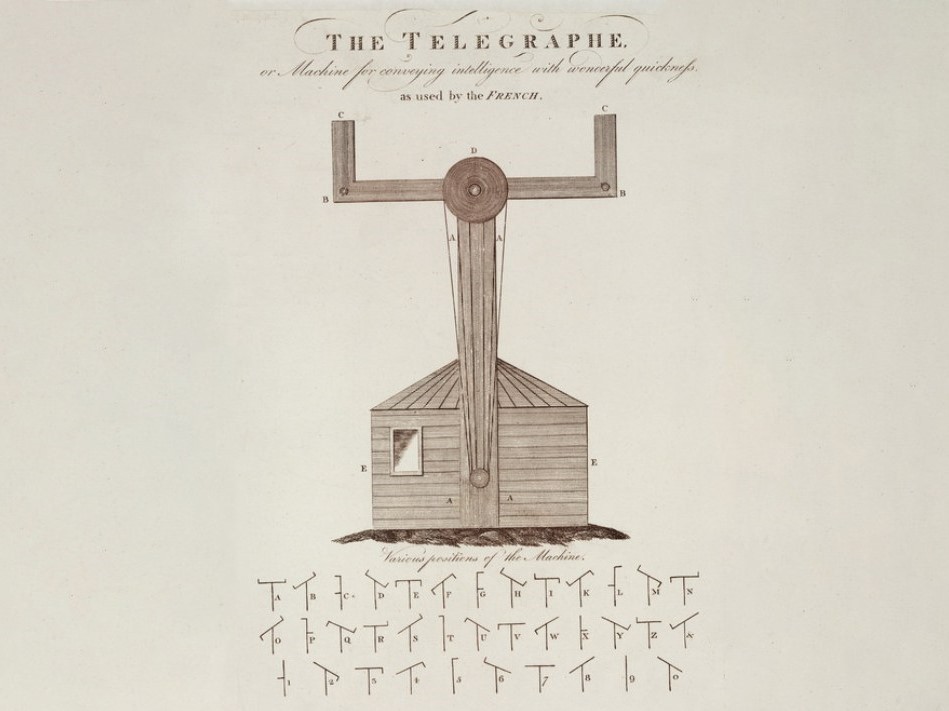

A route for the optical transmission of messages between Paris and Lille, invented by the Chappe brothers at the end of the 18th century and requiring 22 intermediate stations, was established in France. It was called Chappe’s telegraph and also known as Napoleon’s semaphore telegraph. Those semaphore telegraph towers were one of the first examples of optical messaging.

A Chappe tower that was used to send messages showed various letters depending on where the pointer was placed.

A portion of the letters is seen in the bottom of the above drawing. Within minutes of their installation, these systems were able to notify all of France of crucial occurrences. In part, Napoleon Bonaparte‘s military success may be ascribed to his use of these semaphore telegraph towers, which allowed him to issue orders rapidly and efficiently.

Transmission of messages via electric current

Numerous issues plagued optical messaging. For instance, it was conditional on favorable weather, information transmission relied on the vigilant observation and presence of route marshals, and, particularly with early systems, differentiated information transmission was impossible. The security of the communications was also a major challenge.

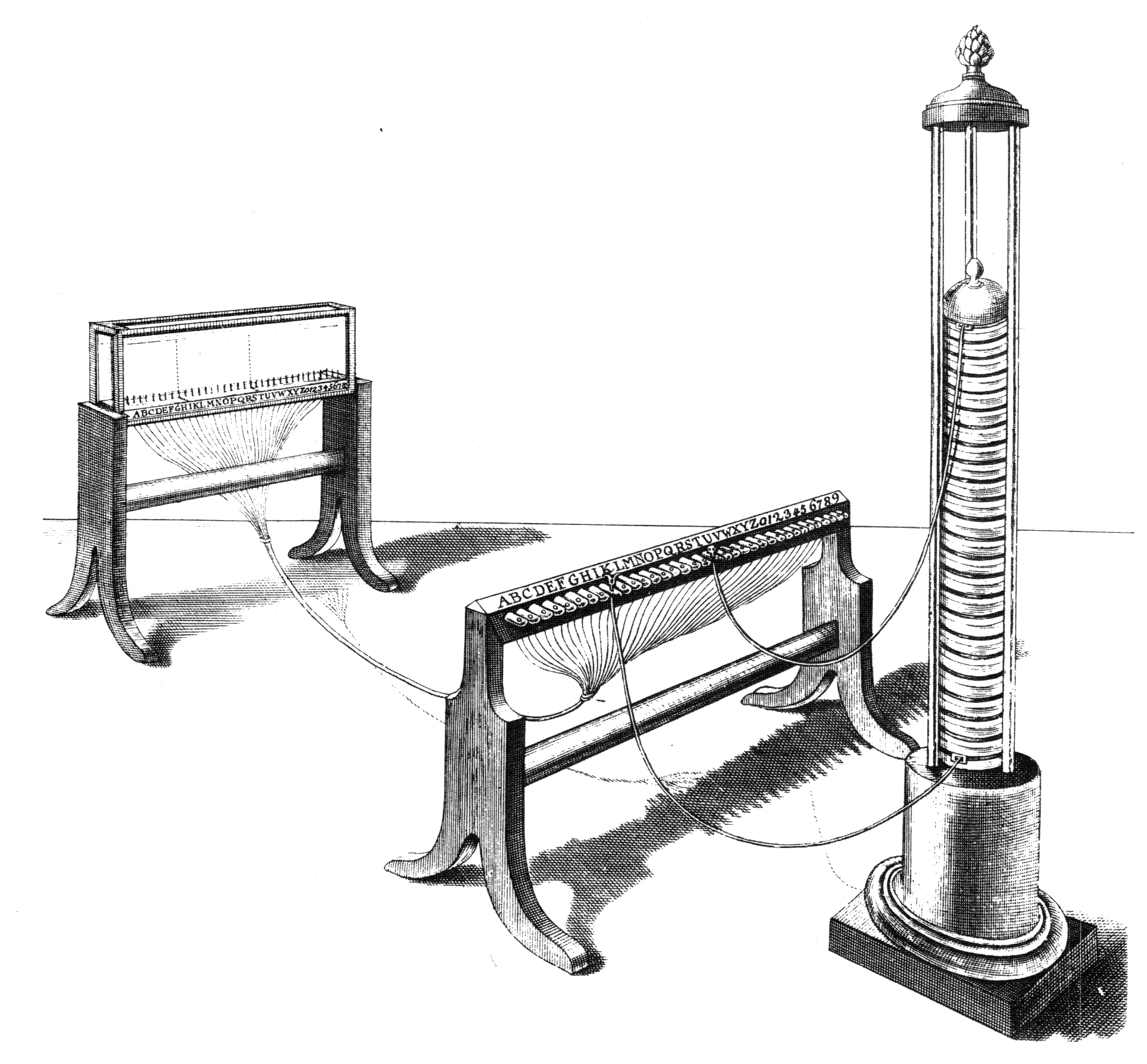

Bavaria’s War Ministry in Germany hired a Munich anatomist named Samuel Sömmering at the turn of the 19th century to establish an optical telegraph service. Sömmering, seeing the shortcomings of optical telegraphs, sought to capitalize on the available electrical advancements by proposing a “galvanic telegraph.”

There were 24 cables connecting the transmitter and the receiver (one for each letter). The Volta column (voltage source) was linked to the wire designated for the intended character (C, for instance). The water box at the receiver’s C-pin began to fill with gas as a result of the current flow (electrolytic decomposition).

First, it was made sure that gas bubbles developed at the pins for the letters C and B on the receiver, signaling the impending arrival of a message. The spoon then floated to the surface of the water. Because of this, the spoon was lifted higher in the water, and the lead pellet connected to the other end of the spoon dropped through the funnel and into the alarm clock D‘s bowl, setting off the alarm.

Bibliography

- Groundbreaking Scientific Experiments, Inventions & Discoveries of the 18th Century, Jonathan Shectman.

- David L. Woods, “Ancient signals”, Christopher H. Sterling (ed), Military Communications: From Ancient Times to the 21st Century, 2008 ISBN 1851097325.

- “Semaphore | communications”. Encyclopedia Britannica.

- Jay Clayton, “The voice in the machine.” ISBN 9781317721826.