In the Modern Era, from the late 15th to the late 18th century, fishing activities were a fundamental concern for coastal populations. These activities could involve shoreline fishing for personal sustenance through a gathering economy or larger-scale fishing to earn money and accumulate significant capital. This capital could then be reinvested in other ventures, such as privateering, as seen with the people of Saint-Malo. Thus, in the modern era, fishing served as a means for coastal populations to maintain their status, develop, and even achieve wealth.

From Gathering to Small-Scale Fishing

To begin with, we analyze the gathering activities that predominated in coastal societies during the modern era. The collection of “fruits of the sea” was common among coastal populations. This term was used by Europeans to describe marine resources readily available on the shore. For example, people gathered seaweed, such as kelp, that was either washed ashore or harvested along the coasts of the Atlantic, the Channel, or the Mediterranean. Other natural materials were also collected, such as pebbles, sand, or rocks dislodged by storms and rough seas. However, from the 18th century onward, authorities began restricting these practices to prevent coastal erosion. For instance, Pampelonne Beach near Saint-Tropez was long used as a sand reservoir for construction across the Côte d’Azur; today, it is a protected and highly sought-after tourist destination.

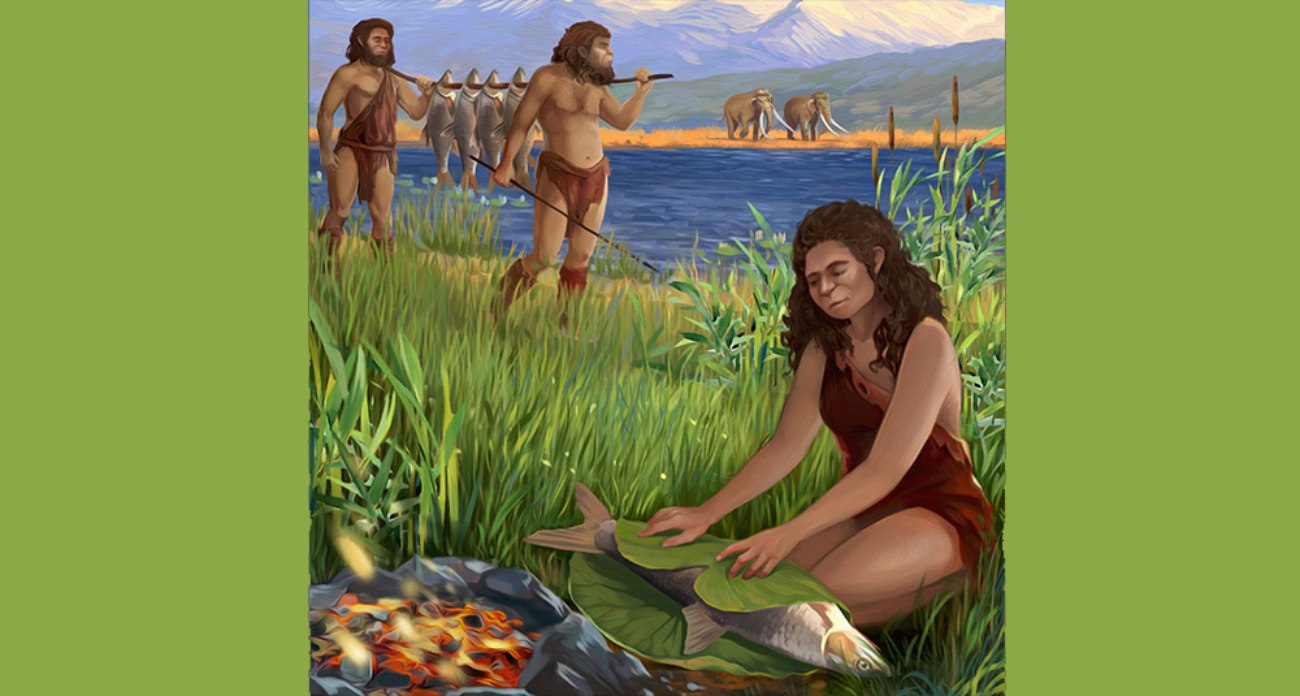

“Fruits of the sea” were also sought after by small-scale shore fishers, who collected various products while walking along the coast. These included shellfish, oysters, mussels, cockles, and the like. This type of gathering primarily occurred in tidal zones, particularly along the waters of the Atlantic Ocean, the Channel, or the North Sea. During low tide, when the “foreshore” was exposed, gatherers would come to these areas to engage in their activities.

For instance, they might collect natural sponges, which were fished in Sardinia, Sicily, Tunisia, and Greek waters.

Another lucrative activity practiced by some was coral fishing. Coral, especially red coral, was highly valued in the Mediterranean and beyond, used in small quantities in pharmacology and extensively in jewelry and goldsmithing. During the modern era, red coral was often presented to notable visitors; for example, when Marie de’ Medici visited Marseille to marry King Henry, she was given a coral branch as a welcome gift.

Among all the marine resources mentioned, salt was the most significant. It was essential for both metabolism and food preservation. Sea salt was obtained using similar methods along the Atlantic and Mediterranean coasts: small dikes were constructed, creating “pans” where water was trapped and eventually evaporated to reveal salt. These systems existed in France, notably in Hyères on the Giens Peninsula, as well as in Guérande and Bourgneuf, and throughout Europe, including Venice and Setúbal.

Until the late Middle Ages, salt marshes were mainly operated by monasteries and feudal lords. However, starting in the 14th century, the state replaced these institutions and organized salt marsh exploitation for its own benefit. In France, the state sought to control salt production by introducing a tax on salt known as the “gabelle” during the Hundred Years’ War.

In all these cases, “shoreline fishing” was omnipresent. It involved fishing on foot, where people would go at low tide to collect shellfish, crustaceans, or small fish with bare hands or a net. It also included small-scale coastal fishing, conducted near the shore using fishing boats. Fishermen would leave the port in the morning and return in the evening, often before nightfall.

However, this type of coastal fishing developed later in western regions compared to the Mediterranean. Until the 15th century, people in western areas like Gascony, Normandy, Brittany, and Flanders hesitated to venture far from the coast due to fears of the “kingdom of the dead,” a context of “repulsion” from the sea.

Offshore and Deep-Sea Fishing

Offshore fishing involved staying away from the coast for several days. In the Mediterranean, this included bluefin tuna fishing using nets. In northwest Europe, it primarily involved herring fishing, a specialty of the Dutch during the modern era. According to historian Alain Cabantous, the Dutch even became a “herring civilization.” However, in the 17th century, herring prices declined, making it a symbol of popular consumption. Preservation techniques improved, allowing the fish to be cleaned, gutted, and packed in barrels onboard or smoked or preserved in jars with water and white vinegar.

Today, herring remains widely fished and consumed in this part of Europe and is symbolically celebrated during popular festivals, such as the maritime carnivals in Dunkirk, Douai, Dieppe, Calais, and Boulogne-sur-Mer.

Deep-sea fishing, mainly practiced near Newfoundland by Saint-Malo fishers, was the most prestigious type of fishing. It generated enormous fortunes, as seen with the fishermen of Saint-Malo, who reinvested their earnings in privateering. Some corsairs used the money earned from cod fishing to arm privateer ships, capture galleons, and further their fortunes.

Deep-sea fishing involved leaving the home port for several weeks to fish in the high seas. Newfoundland’s fishing grounds were frequented and explored from the early 16th century when Europeans searched for a northern passage around the Americas. The most sought-after fish in this area was cod. Norwegian fishers from Bergen were the first to target this species, much larger than the herring favored by the Dutch.

Soon, these Scandinavians were imitated by other European cod fishers, notably the English and French. As a result, Newfoundland became a political hotspot and a focal point of international relations among European states. For instance, after the War of the Spanish Succession, the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713 required France to cede much of Newfoundland to the English.

However, France retained a few small islands, such as Saint-Pierre and Miquelon, enabling continued deep-sea fishing activities.

Cod caught for European consumption was prepared in two ways: salted and dried onshore (known as “codfish” or “bacalhau”) or preserved onboard in brine (known as “green cod”). The latter required less preparation but had a shorter shelf life. These techniques illustrate the innovative methods fishermen employed to optimize their yields.