Switzerland was the first nation to add iodine to its salt supply in 1922, doing so to prevent iodine deficiency, which may lead to major health problems including cretinism and goitre. This regulation is still in effect across the country. This decision is solely responsible for the disappearance of local goitre and cretinism, which used to bother Napoleon and frighten tourists. Iodine deficiency is on the rise again because of public health initiatives to discourage salt use. The Swiss Federal Commission for Nutrition has upped dosage recommendations to address this issue as of early 2014.

The human body can’t function without iodine. Yet, it is one of the most common micronutrients in ocean water. Seaweed, fish, and shellfish all collect iodine. However, there is very little of it in the ground in landlocked nations like Switzerland and its Alpine neighbors. Those that eat the products of this land suffer from an iodine deficit as a consequence, which has been linked to major mental and physical health issues beginning in early embryonic development.

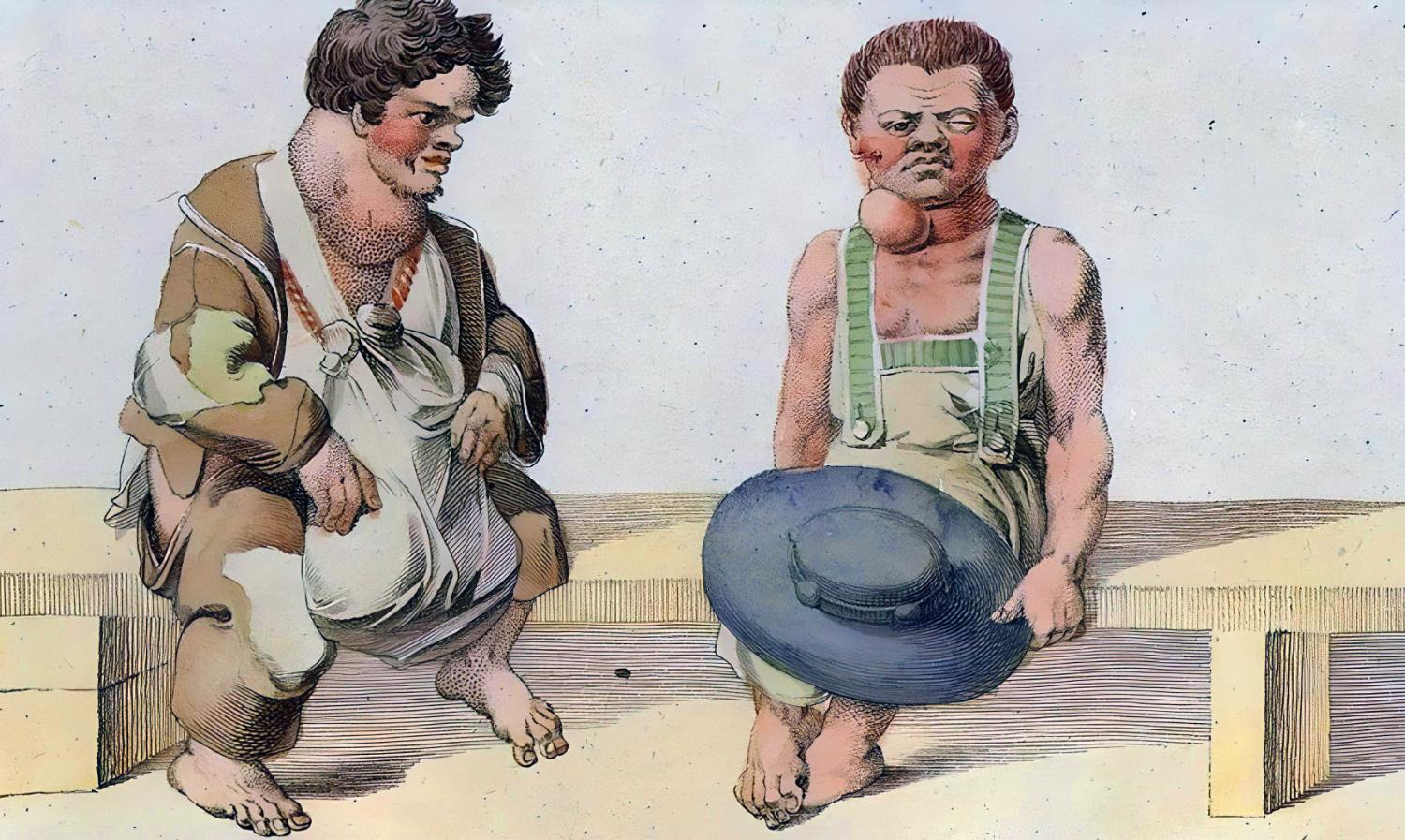

Thyroid dysfunction and aberrant growth have been linked to iodine deficiency. For decades, visitors to Switzerland have been shocked by the high prevalence of goitres among Swiss citizens; in certain cases, this condition has been found to coexist with low height, mental retardation, deafness, and mutism. The frequency of goitre among the 76,000 Bernese pupils examined between 1883 and 1884 ranged from 20% to 100%.

For a long time, the Alpine population’s image was harmed because of cretinism brought on by an iodine deficit. Napoleon Bonaparte, dissatisfied with military recruiting in the canton of Valais in Switzerland (then a French department), ordered a census of “cretins” in 1810. Only around 4,000 people out of a total population of 70,000 were a close match. Also, the salt baths in the Saxon region of the country were the subject of heated debate as well. The original owner in the 19th century spread the myth that the baths had been iodized by sea salt. But the iodine was intentionally added to make it seem natural.

However, this trace element did have an impact. A doctor in the Zermatt Valley saw a significant decline in goitres after administering low dosages of iodine to local residents (including the town baker and some cattle). The head surgeon of Herisau hospital, Hans Eggenberger, persuaded the administration of iodine in the Appenzell-Ausserrhoden canton to conduct a statewide experiment of salt fortification in 1922 based on his suggestions.

This region was chosen since individual consumption of salt tended to be rather constant. Adding iodine to the salt was a straightforward procedure that Eggenberger was doing on his own. Half of all babies in Switzerland had palpable thyroids. However, after a year of iodine fortification, or “salt iodization,” the condition fully disappeared.

The Swiss Confederation adopted the Appenzell people’s practice of adding 3.75 milligrams of iodine per kilo of salt in November 1922, and the Swiss Rhine Salt Works was the only supplier to 24 of the 25 cantons ever since.

Thus, Switzerland was the innovator of thyroid treatment. The United States adopted a similar salt iodization strategy in 1924, which was afterward copied by numerous other nations.

Iodine deficiency is still a problem around the world, with two billion people thought to be affected. It has been estimated that a 10–15 point drop in IQ might result from even a mild iodine deficiency. The World Health Organization (WHO) is a staunch advocate for adding iodine to salt, and several governments have made it obligatory.

Not in Switzerland, however; there, it’s always been entirely opt-in. Opponents have always existed, particularly those concerned about the possibility of overdosing. Many are opposed to having the government dictate what they eat. The notion is that you can’t medicalize people without obtaining their input. This is often cited as one of the main reasons why fluoride has not been added to the water supply in the Swiss city of Basel for the last decade.