The samurai is one of the most iconic figures associated with the history of medieval Japan. One of the most intriguing and memorable eras in the history of the Empire of the Rising Sun is the time of feudalism and civil wars. But all that preceded was plunged into the shade. As the 19th century drew to a close, the question of how Japan developed into a feudal empire sparked widespread interest. Together, let’s explore the ancient Japanese past, from prehistory to the rise of the imperial shogunate.

- At the dawn of Japanese history: The Jomôn period (14000 BC–300 BC)

- Japan and China: The Yayoi period (300 BC–300 CE)

- The Emerging Empire: The Kofun period (300 AD–538 AD)

- Shōtoku Taishi’s Reforms (587–628)

- The Taika Reforms

- The introduction of Buddhism in Japan

- Development of Japanese arts and culture

- Buddhism in the Empire of the Rising Sun

- Buddhism, a state religion? No, but…

- The Fujiwara Regency

- The rise of the military class

- The Genpei War, 1180–1185

- Emergence of the Samurai: The Kamakura Period (1185–1333)

- The Kenmu Restoration (1333–1336)

- The Muromachi period (1337–1573)

- Nanban and gunpowder

- Gekokujo: The powerful are defeated by the humble

- The Unification of Japan: Oda Nobunaga (1534–1582)

- Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1536/37–1598)

- The Tokugawa Leyasu period (1543–1616)

At the dawn of Japanese history: The Jomôn period (14000 BC–300 BC)

The Shinto goddess Amaterasu was said to have provided the divine ancestry for the Japanese imperial family, giving them the right to rule the country. The Empire was just imperial in name at first, though.

While evidence of human habitation in Japan can be traced back to before 14,000 BC, the archipelago did not begin to take shape until around 300 BC. Peasants and fishermen made up the vast majority of Japan’s population at the time, and they lived in seasonal settlements that migrated across the country. The people who lived during the Jomôn period were known as “the market gardeners’ civilization” because they engaged in fishing, hunting, and primitive types of agriculture.

There was no such thing as money at the time, but jade daggers, ceramics, and shell-crafted things were beginning to emerge as popular handicrafts. Dogû is a kind of elaborate pottery that was discovered during the late Jomôn period, about 400 BC. There is no doubt that these works of art originated in Japan.

There was no Buddhism there at the time, just diverse shamanic rituals. It was believed that shamans could tap into the unseen realm and predict the future. They pray for prosperous harvests, appease the spirits, and protect against natural disasters and bad forces.

Japan and China: The Yayoi period (300 BC–300 CE)

A dramatic shift in Japanese culture occurred at the start of the Yayoi period, about 300 BC. At this time, Shintoism was developing, governmental structures were being put in place, and trade with China was beginning to take place. The Yayoi, who came in from northern Kyûshu, the southernmost of the four main islands that make up the Japanese archipelago, were the ones who introduced these novelties.

Around 100 BC, Japan began producing its first metal goods, while the raw materials presumably originated in Korea. Communication with the Chinese and Koreans brought metalworking techniques, including bronze and iron, to Japan. Rapidly spreading from its origins in northern Kyushu, this groundbreaking idea has already changed the face of the whole island. Iron tools were put to use in farming, and the subsequent rise of the rice culture isolated and confined the rural population to their fields and homes made of mud and straw. Also, this system was only possible because of the rise of the settled population.

Wealth was amassed by landowners, passed down through generations, and bolstered the power of the ruling clan. Over time, they developed into something like feudal lords, complete with the power to impose taxes as well as administer justice and religious ceremonies. It was during this period that the first clans emerged. This aristocratic class’ religious function also bolstered their influence in politics. It was only they who had access to the holy items, could communicate with the other side, and understood the rituals of worship to the letter. The respect and admiration of others are a direct result of this accomplishment, further solidifying their position as leaders. Since bronze was less practical than iron for agricultural labor, it was relegated to the role of a symbol used in ceremonies, which eventually became an integral part of the governmental system.

In other words, the Yayoi era did not mark the end of the old shamanistic practices that had existed since the Jmon period. Shinto, a religion with animist and polytheist elements, is still widely practiced in modern Japan. Shinto was founded on the idea that there were “6 million gods,” also known as kami (or spirits), who resided inside of everything and stood for each natural element. For instance, the fox deity Inarimyojin, who was revered for his role in the harvest, was one of the most important kami.

In order to ensure a bountiful crop, they prayed to him. Shinto’s emphasis on cleanliness was similar to that of other religions. A person must periodically pray and do particular rites to rid themselves of their impurities (kegara), or else they will bring unhappiness and disaster upon themselves and everyone around them. The foundational myths of Japan, such as that the goddess Izanami and the god Izanagi created the country, have their origins in the Shinto faith.

The Japanese, who were known as the Wa at the time, first appeared in written Chinese. The fabled empress Himiko of Yamataitoku, who served as temporal ruler and high priestess, is said to have founded the empire around the third century (yet another fusion of spiritual and temporal powers). This empress may have existed, and she may have had some bearing on the later Yamato rule (from which the renowned battleship Yamato takes its name), although none of these claims have been verified.

The Emerging Empire: The Kofun period (300 AD–538 AD)

The Yamato court established itself as the imperial family at the end of the third century. Along the coast of the inland sea, the clans of the Bizen area rose to prominence and eventually came to dominate the southern half of Honshu and the northern half of Kyushu. Clans such as the Soga, Katsuraki, Heguri, and Koze were at the forefront of society. They were soon joined by the Kibi clans of Izumo (to the northwest), Otomo, Mononobe, Nakatomi, and Inbe. Each of these families continued to exercise control over its own kuni (area), but they worked together as a whole under the guidance of the Yamato shogunate. Particularly significant were the Soga, Mononobe, and Otomo. They all believed they sprang from royal or supernatural bloodlines. During a succession conflict towards the end of the fifth century, the Otomo, who supported Emperor Keitai, overthrew the previously dominant Katsuraki.

Positions like the Minister of the Treasury arose when the Yamato court established its own administration. The Emperor’s rule was absolute; even the clan chiefs had to adhere to it if he allowed the clans some degree of autonomy on their territory. However, in reality, one clan was generally more powerful than the others, often via matrimonial connections with the Emperor’s family.

The earliest hereditary titles of nobility were bestowed on the aristocracy, made up of members of the clans under the guidance of their patriarch. The use of cavalry and other elaborate military innovations emerged during this time. Swords were also first used about this time.

The Yamato court was given special access to the Middle Kingdom and Korea. The Wa (Japanese) Emperor started paying tribute to the Chinese Emperor around the end of the 5th century, and in return, the Chinese acknowledged him as their legitimate ruler.

The archipelago had a large influx of Chinese and Korean immigrants, some of whom settled and started families. Notable examples are the Takamuko and Hata clans, both of whom trace their ancestry back to the Qin period of China. In return for Japanese military assistance against the Manchu tribes, the Korean princes were transferred as captives to the Japanese court.

The introduction of Buddhism to the soil of the Japanese archipelago was only one of the unintended results of such a large inflow of people.

By the conclusion of the Yamato period, Japan had established itself as a powerful kingdom, respected even by its non-Japanese neighbors despite its unique Shinto-based governmental and cultural system. Nonetheless, Japan did not reach its imperial period proper until the Asuka period, which occurred long after the introduction of Buddhism and the subsequent reforms.

The Yamato court, which had its beginnings in the fifth century, grew into the imperial court of Japan during the next six centuries, becoming more dominant both domestically and internationally. It all started with a series of changes in the sixth and seventh centuries that completely altered the country’s political structure. During this period of imperial rule, the arts, cultural and spiritual traditions, and even the written language advanced, despite the fact that war was uncommon. Without a doubt, the six centuries between the beginning of the Heian period and the end of the Muromachi period were the Golden Age of the Empire of the Rising Sun, which became known as Japan during this time (Nihon). However, the shift between the Emperor’s ascension to power and his consolidation of that authority was characterized by a wave of changes that were essential to the Empire’s survival.

Shōtoku Taishi’s Reforms (587–628)

Extreme political intrigues took place at the Yamato court around the turn of the sixth century. Because of their marriage into the royal line, the Soga clan gradually came to dominate, to the detriment of the Katsuraki, Heguri, and Koze clans, and notably the Mononobe and Nakatomi clans, who opposed Buddhism’s introduction to Japan. But, we would return to this point. In 587, with the support of prince regent Shōtoku Taishi, the Soga clan was strong enough for Soga no Umako, the leader of the clan, to establish his nephew on the throne and govern through this man (or kid, rather) of straw (574-622). When that happened, Suiko, the empress, became ruler after the emperor was killed for being overly adamant about his own authority (593-628). Shōtoku Taishi was the pioneer in instituting change.

He was a devout Buddhist and a serious scholar of Chinese literature, and he took the Confucian ideals that guided the Middle Kingdom’s administration and adapted them to Japan. Shōtoku Taishi created the idea of the “Mandate of Heaven,” which states that the Emperor had absolute authority since he was chosen by God and was tasked with ruling the world in accordance with the intent of the heavens. In addition, he penned a constitution consisting of seventeen articles, in which he advocated for a number of ideas (including the importance of harmony and the Buddha’s teaching, the supremacy of imperial orders over all others, and the virtues of devotion and obedience as espoused by Confucianism). This “constitution,” a term that was debated because it doesn’t really set up the institutional foundations of the state but rather its moral and spiritual guiding principles, was accompanied by a revolution in the system of ranks and etiquette, which, as funny as it may seem from the outside, was very important in a highly ritualized political system.

Buddhist temples were erected, the Chinese calendar was adopted, and a new administrative entity, the Gokishichido, modeled after the Chinese system, was instituted to complete Japan’s “sinicization” (5 cities, 7 roads). China, when ruled by the Tang dynasty, was the destination for many students and diplomatic missions. Although cultural ties were stronger than they had been during the Kofun period, animosity between China and Japan began to grow at this time. In fact, the Japanese no longer saw themselves as a tributary state to their Chinese neighbor, and dispatches from the Emperor of the Rising Sun were addressed to the Emperor of the Middle as if they were equals.

The deaths of Shōtoku Taishi and Soga no Umako left the Soga clan in control of the Japanese Empire, and by this time, the influence of Chinese culture had infiltrated Japanese society. Even though people were skeptical at first, especially about Buddhist rituals, these foreign practices would come to shape Japan’s unique culture over the next few hundred years.

The Taika Reforms

However, with Shōtoku Taishi’s death, the Soga clan collapsed and was never seen again. There was a coup d’état in 645 that was planned to destroy the Soga dynasty because of court intrigues. This uprising, known as the “Isshi incident,” was the catalyst for the Taika reforms, often known as the “Great Reformation,” and was headed by Naka no Oe and Nakatomi no Kamatari (of the clan that would later become the Fujiwara clan).

When land ownership ceased to be passed down via families, the federal government took it over. Land was transferred to the imperial government for redistribution at the end of each generation. Obviously, this suggests that the end of a disfavored family is as easy as snapping one’s fingers. Clan chieftainships, which had previously been passed down through the generations, were similarly abolished.

Taxes on silk, fabric, and cotton were implemented to fund the expansion of the government, and a corvée was set up to permit the formation of a military and the erection of public buildings. At long last, the Gokishichido system was dissolved, and the nation was split up into provinces governed by governors who reported directly to the imperial government. Districts and townships were set up to give the government of the country even more precise control.

The Emperor and his allies, most notably the Kamatari, also began working to build the ritsuryo. It was an official code of conduct that included both criminal and administrative provisions. The first version of the ritsuryo, known as the Ômi code, was finished in 668; the second version, known as the Asuka Kiyomihara code, was completed in 689; and the most current version, known as the Taihô code, was completed in 701 and remained in use, with a few features changed, until 1868. Similar to Confucian law, the criminal code emphasizes rehabilitation over retribution.

The Daijo-kan formed the eight ministries of central administration, ceremonies, the imperial palace, civil affairs, justice, the army, people’s affairs, and treasury, while the Jingi-kan oversaw court rites and Shinto customs. This potent instrument improves the imperial house’s capacity to administer the nation and helps maintain its hold on power.

The introduction of Buddhism in Japan

Buddhism was most likely brought to Japan by Korean immigrants. Following Japanese assistance to the Baekje kingdom against Manchu invasions, ties between the Yamato court and the Korean kingdoms remained warm throughout the sixth century. The first missionary group to go to Japan to promote Buddhism did so in the year 538. At first, the populace, led by the Nakatomi and Mononobe clans, was opposed to Buddhism, but it was quickly accepted by the Soga clan and disseminated to the whole nobility.

The Shinto religion, on the other hand, was waning as Buddhism spread over Japan. By imperial edict, the practice of burying one’s dead in a kofûn, a tumulus in the form of a keyhole, was outlawed. Horse, bird, and dog meat were also taboo to ingest.

And Buddhism wasn’t the only worldview to make the journey to the islands. Around the middle of the seventh century, Mount Tonomine was the site of the first Taoist monastery in Japan. As evidence of the longevity of this implementation, certain imperial tombs would be constructed in the form of an octagon, which in Taoism represents the universal order.

By the time of the end of the Asuka period, the empire was well-established, the clans and the people were committed to it, the political environment was tranquil, and no war tore the archipelago apart. As a result of this success, the Japanese Empire saw itself as on par with the Middle Kingdom. A real cultural bloom was about to happen in what was now known as the Empire of the Rising Sun.

In 710 CE, the city of Nara became the capital of Japan, marking the beginning of the Nara period. Nara became home to a new kind of bureaucracy at the imperial level as a result of the Asuka period’s reforms. Rapid population growth helped make it Japan’s first major metropolis, eventually home to over 200 thousand people.

This urbanization, which attracted thinkers and artists from across the country, sparked a veritable cultural explosion that saw the decline of the Chinese culture brought by Buddhism (despite the fact that the capital was constructed using the same blueprint as the Chinese capital of the Tang dynasty) in favor of the emergence of a uniquely Japanese way of life. People often think of the Nara and Heian periods as Japan’s artistic renaissance, but they were also linked to the end of imperial rule and the rise of clan conflicts because the court couldn’t solve its own power struggles.

Development of Japanese arts and culture

Beginning in the year 710, Chinese titles and court garb were no longer used, marking the beginning of a period of cultural rejuvenation. As standards of beauty change, it’s not only women in the nobility who use powder to brighten their complexions and darken their teeth. Men began to have tiny moustaches, while women began to paint their lips crimson in an effort to emulate the celestial “purity” attributed to Shinto deities in mythology. The first elaborate court gowns also debuted at this time. Known as “junihitoe,” these garments were constructed from many layers of cloth and organized in a sophisticated code that changed with the seasons and religious holidays.

When comparing the artistic growth of these two periods, literature stands out as the clear winner. A literary boom occurred with the introduction of “kanas,” characters meant to represent particular Japanese characteristics, even if Chinese remained the court language. In the early Nara period, the Kojiki (712) and the Nihon Shoki (724), the first imperial chronicles, were published. Fictional works followed, including the groundbreaking Tale of Genji by Ueda Hideyoshi and Sei Shonagon’s Book of the Pillow. The evolution of poetry was equally noteworthy. Japanese poetry, known as waka, thrived throughout this time period because poets were seen as having the most refined and peaceful of minds. Among the most renowned Japanese poets were Fujiwara no Teika, Murasaki Shikibu, and Saigyo.

The present national song of Japan, the Kimi Ga Yo, was composed around the beginning of the Heian period, in 800, which gives some idea of the magnitude of the literary works of the time.

Buddhism in the Empire of the Rising Sun

Even though the Tang dynasty court was seen as decadent and Chinese customs were fading out of use, imported Buddhism from China remained popular. The Buddhist clergy, who had already established themselves across the archipelago, made hasty efforts to adjust to life in Japan. This was very personal to the Nara emperors and empresses, and it did not end well for them.

The early Nara period was a time of great success for Buddhist teachings. At the start of the period, a massive monastery complex known as the Todaiji temple was constructed, housing a colossal bronze Buddha statue known as Daibutsu, which stood at over 16 meters in height. This monument brought together two distinct religious traditions: the continental Buddhism that had been imported to Japan and the ancient Shintoism that had been practiced in Japan for millennia. It was still standing in Nara, where it has become a prominent landmark for both domestic and international visitors. In order to spread Buddhism to the countryside, where Shintoism was still popular, provincial temples (known as kokubunji) were founded to serve as centers of worship and education.

The huge Mount Hiei monastery, the oldest in the archipelago, was constructed at this time by Tendai Buddhists who were close to the monarch and who based their theology on the Lotus Sutra. The Shoso-in temple in Japan preserved holy manuscripts from as far away as the earliest caravanserai in Central Asia, proving that cultural triumphs and works of art from all across the Buddhist world eventually made their way to Japan. Paintings on silk, Buddhist sculptures, temple decorations (mandalas), sculpture, and calligraphy all contributed to the spread of Buddhism in Japan, as did the production of sacred works of art.

Buddhism, a state religion? No, but…

Despite the fact that Buddhism was no longer the official religion, it was nonetheless used by the imperial family as a tool to maintain and expand their dominance. During her reign, Empress Kôken (749-758) welcomed many Buddhist monks to the Imperial Court. Despite her resignation in 758, she maintained close relations to the monks, particularly a priest called Dokyo. When her cousin Nakamaro of Fujiwara rose up against her, she defeated him and deposed the emperor in the process, returning to the throne as Empress Shotoku (764–770). These events startled the court to the point that women were removed from the line of succession. The empress had about a million woodcut charms manufactured to thank the gods for her triumph, demonstrating the participation of the church in her reign.

Later, during the Heian period, several aristocrats, most notably Emperor Kammu, a great fan of the Tendai movement, lent their support to the Tendai and Kukai Buddhist sects. Both of these movements sought to strengthen ties between the church and state on the grounds that effective religious practice required access to positions of power in government. During this time, clerical landholdings also became more significant. While the monasteries were exempt from taxes on the basis of their religious character, they were also a major contributor to the imperial government’s budget deficit.

Although the Nara period and the early Heian period saw a cultural boom, owing in large part to the development of the present form of Japanese writing and the spread of Buddhism, the imperial authority that had looked unbreakable began to show signs of weakness at this time. The Heian period was marred by internal strife, which ultimately led to the collapse of the empire and the rise of the shogunate.

The transformation from the Nara to the Heian period was quite subtle, especially considering the significance of the events that are often at the heart of era transitions. With the transfer of the capital from Nara to Kyoto in 794 (then known as Heian-kyo). Kyoto, following the same blueprint as Nara but on a larger scale, was a true monument to the zenith of the imperial age.

While the Nara period and the early Heian period saw a cultural boom due to the development of modern forms of Japanese writing and Buddhism, the first fractures in what had looked to be the Golden Age of imperial authority began to show during this time. The Heian period was marred by internal strife, which ultimately led to the collapse of the empire and the rise of the shogunate.

Given the significance of the events that are often at the core of era shifts, the transition between the Nara and Heian periods goes nearly overlooked. The city of Nara was abandoned and replaced by Kyoto as the capital in the year 794. (then known as Heian-kyo). Kyoto, modeled like Nara but constructed on a grander scale, stands as a fitting tribute to the zenith of the imperial period.

Because of its proximity to the sea and rivers, and because it was more easily accessible from the eastern provinces, Emperor Kammu decided to relocate the seat of imperial authority to Kyoto. Kammu intended for it to become an imperial stronghold by making it the political hub of the whole archipelago. One of the first steps toward victory was the Japanese military’s conquest of the northeastern region of Honshu. However, the implosion of imperial power had already begun to sprout.

The Fujiwara Regency

The death of Emperor Kammu in 806 left a formidable throne but a contested succession, despite the fact that the Empire seemed to be headed in the right direction. Coincidentally, the major aristocratic families also started to restore the influence they had lost during the reforms of the sixth century. As a result of the changes, individual farmers and peasants who previously managed their own land now find it more profitable to sell it to these groups. Afterward, they became sharecroppers, laboring on these farms in return for a cut of the crop profits. This shift led to a dramatic rise in the quantity of property owned by the nobility. These estates were called “shoên” and were controlled from a home such as a mansion or castle.

The only difference from the medieval European system was that the peasants were not bound to the land as serfs. While commoners may be unable to stop the state from seizing their property and collecting taxes on it, the great aristocratic families might use their influence to negotiate substantial tax cuts. The situation at monasteries was quite similar. The monks also formed shoên and eventually became significant economic forces in the nation.

Gradually, as the empire’s financial resources dwindled, the emperors lost complete authority over the government. The Fujiwara were a strong aristocratic family in Japan who possessed extensive arable lands in the country’s north and who eventually became very close to the royal family via marriage. In the ninth century, numerous members of the Fujiwara family served as regents and took over as leaders of the imperial government. Their family’s administration also handled the management of their land holdings and, eventually, the empire’s affairs. The Fujiwara family more than quadrupled the number of high-ranking imperial bureaucrats.

While maybe not as elaborate as the Fujiwara’s, other clans still created their own systems of government. Feudalism’s foundations had been laid.

The rise of the military class

The imperial army’s ability to be funded and maintained became an issue when the empire’s economy crumbled. After a while, the aristocratic families were just as responsible for military control as the imperial authority. In addition, the shoên served as both the impetus for and the means of the growth of organized military forces. They provided the resources necessary to pay and feed the soldiers who, among other things, protected the shoên from robbers and Emishi (tribes from the north of Japan) raiders. Warriors (bushi), subsequently dubbed “samurai,” emerged as a new social class with the formation of private militias under the command of aristocratic families and religious groups (those who serve).

Because they could field larger armies on their vast estates, the most powerful families in the empire were given military titles and a higher status at the imperial court. Some families, including the Taira, Fujiwara, and Minamoto, rose to prominence in the military. The situation became heated as all three clans mistrusted one another yet were reluctant to start an outright war with one another. Ultimately, it was Emperor Go-Sanjô who tipped the scales (1068–1073).

He was able to curb Fujiwara’s influence, unlike many of his predecessors. He created a formal land registry, and as many Fujiwara holdings hadn’t been officially registered with the government after being purchased from individual farmers, the clan was forced to forego a significant portion of their property and revenue.

The Fujiwara were finally driven from their dominant position and into their northern strongholds by the Hôgen rebellion (1156), which was backed by the Taira and the Minamoto. Although they remained in their roles as emperors, the current emperor took over control of the government and formed an imperial council of abdicating emperors. The family’s collapse was hastened by strife inside. When a huge clan’s dominance was finally broken by conflict, it was the first time that this had ever happened.

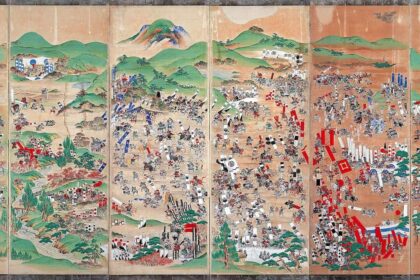

The Genpei War, 1180–1185

The Gempei War was Japan’s first true civil war, and it occurred shortly after the collapse of the Fujiwara, a family that had been pushed to the political outside. From 1180 on, this one battled against the Minamoto and Taira dynasties. There were indicators of an impending big battle going back many decades. The Minamoto initially rebelled against Taira rule of the imperial court in 1160, during the Heiji rebellion, but were soon put down.

The Taira clan, led by the legendary Taira no Kiyomori, controlled imperial politics during the period. He had the nerve to become clan chief and then seize control of modern-day Kobe, the hub of the busiest commerce route between Song China and Kyoto, the imperial capital. Because of this, he was able to provide a comfortable lifestyle for his loved ones while still advancing his career and gaining influence. Kiyomori created and unmade monarchs (Nijo, Rokujo, Takaku) as he pleased in his role as Daijo Daijin (Chief Minister of the government, second in power only to the Emperor) and administrator of the Empire.

By doing so, the Taira earned the enmity of many in the court who were envious of their authority. Assisted by the Minamoto family, Prince Mochihito, brother of the deposed Emperor Gosanjo, started the war in an effort to end the Taira dynasty’s rule. When Mochihito issued a summons to arms, the latter responded by relocating the capital to Fukuhara (current-day Kobe), which was inside the center of their fief.

In the summer of 1180, troops from both families converged, and in the first fight, at Uji, the Minamoto were utterly defeated. Despite the assistance of the warrior-monks of the Mount Hiei monasteries, Prince Mochihito and the Minamoto clan chief, Minamoto no Yorimosa, were both slaughtered. The Taira forces besieged and ultimately destroyed most of these monasteries. The Minamoto were beaten for the second time on September 14, 1180, in Ishibashiyama, and so they withdrew to their seaside stronghold of Kamakura. Taira no Kiyomori passed away in February of the following year, putting his youngest son in line to become shogun. With both forces separated by hundreds of kilometers and experiencing supply issues due to weak crops, fighting froze in the spring of 1181.

After two years of doing nothing, the army resumed its advance in the spring of 1183. Although the Minamoto were unprepared and their warriors were untrained, the Taira were nonetheless totally destroyed by them at Kurikara. With time, the Taira were unable to escape Kyoto and were forced to retreat to their homelands in western Honshu and Shikoku. Infighting between Yoshinaka and Yoshitsune, two members of the Minamoto family, over who would rule the clan meant that the Taira never fully recovered from the catastrophes of 1183.

After besieging Ichi no Tani and Dan no ura, they were eventually defeated in the naval battle of Shimonoseki in the Inland Sea. After the Taira family was annihilated, the Kamakura Shogunate took power. The chief of the Minamoto clan became Japan’s military dictator, known as the Shogun. As a result of this conflict, the emperors were demoted to the role of symbolic figures, while the shogun assumed practical control for the next 500 years. The samurai emerged as Japan’s new elite class when the country entered its feudal period.

In 1185, the Minamoto clan triumphed over the Taira clan and became the dominant family in the Japanese archipelago. The Taira family’s former dominance and influence over the government were history. However, the war proved the superiority of military might over imperial control. For a long time, samurai were seen as little more than powerless slaves, but over time, they started to establish a warrior caste and assume more responsibilities. Shortly after the Minamoto triumph, the imperial court reinforced this status quo by bestowing upon Minamoto no Yoritomo the title of Seii Tai Shogun, therefore vesting absolute authority in him.

Emergence of the Samurai: The Kamakura Period (1185–1333)

In 1185, Minamoto no Yoritomo, the first shogun in centuries, erected the seat of his so-called bakufu government (tent government; so-called because the military commanders held the authority there) in Kamakura, some 50 kilometers from modern-day Tokyo, ushering in the Kamakura period. The first thing Yoritomo did, as with every new ruler, was to strengthen his hold on power. He established three cabinet-level ministries to better run the country. The first was in charge of the organization’s finances and management. When peacetime rolled around, he administered justice, and when wartime rolled around, he marshaled the shogun’s vassals to raise an army. The latter made sure that the shogun’s orders were followed.

The Kamakura shogunate also relied on the territory it ruled over as a source of authority. With the Taira defeated, the Minamoto were able to seize control of a large swath of central and western Japan. The Minamotos gave these territories to the people who would serve as their vassals, therefore securing their allegiance. At this time, landowners and their vassals vowed devotion and battled for their master, giving rise to the feudal system and the samurai caste.

When Yoritomo was putting this new system in place, he ran into opposition from traditionalists who didn’t like the idea of change. The Fujiwara family, which controlled the majority of northern Japan’s territory, adhered strongly to established norms and customs. The Minamoto were seen as dangerous upstarts by the imperial government. However, the Fujiwara would not accept responsibility from people they considered to be their enemies. Finally, the situation deteriorated to the point that a new civil war broke out, much more quickly than the last one, and concluded in 1189 with the loss of Fujiwara no Yasuhira and the end of the authority of the Fujiwara, who never recovered.

A decade after Yoritomo’s death in 1199, the political landscape of Japan had changed drastically. The new landowning families, vassals of the Minamotos, assembled in the Kamakura court while the previous royal court remained in Kyoto. There were now two legitimate government hubs in Japan.

The Minamoto dynasty had already begun to crumble before Yoritomo’s death, though. After showing signs of easing during the fight against the Taira, internal strife returned in full force. Yoriie, his son, took over as head of the clan after him, although he was unsuccessful in continuing the Minamoto’s hold on the shogunate. In the early 13th century, a military clan called the Hôjo took over the role of Regent (Shikken) and established the offices of Tokuso and Renshô, both generally honorary titles that were used to rob the Minamoto shogun of their authority. The Hôjo effectively replaced the shoguns as the ruling class.

Although the shogunate was established to recognize people who protected the emperor’s authority, the shogun’s authority eventually grew to rival that of the emperor himself. Emperor Gô-Toba went to war with the Hojo shogunate in 1221 after declaring the second Hojo regent, Yoshitoki, an outlaw. In a little over a month, the Hojo family and its allies annihilated the imperial armies and banished Go-Toba and his sons. The emperor’s rule was effectively ended by this rebellion, known as the Jokyû, and he became a mostly ceremonial figurehead.

Success led the Hojo rulers to create a new political tool in 1225: the Council of State, where the other lords met and shared judicial and legislative authority. Even while the shogun and regent were still the most powerful figures in the country, they were able to delegate part of their authority to other clans and so lessen the likelihood of a coup. A new set of laws came into effect in 1232. This new code, the Goseibai Shikimoku, was a radical departure from the preexisting norms; it was wholly founded on the teachings of Confucius, but it was more clearer and more practical in application since it was narrowly focused on the formulation of laws and specific penalties according to offences.

The Hojo regents maintained absolute authority for around fifty years. Until the first Mongol invasion of Japan in 1274. In 1268, the Mongols under Kublai Khan created the Yuan dynasty and began ruling China. The latter desired to include Japan among his vassal states and hence issued an ultimatum demanding that Japan surrender and pay tribute. The Hojo regents promptly rejected the ultimatum. About 23,000 Mongols, Chinese, and Koreans arrived on the northern part of Kyushu in a fleet of 600 ships in 1274, armed with grenades that had never been seen in Japan before.

Unfamiliar with the group formations utilized by the Mongolian commanders, the samurai swiftly fell behind. The Mongol fleet was devastated by a storm less than a day after its arrival. On 1281, Kublai Khan attempted a second invasion, but his fleet was again wiped out by a storm after a seemingly successful landing and a few weeks of combat in Kyushu. These storms were deemed kamikaze by Japanese Shinto priests because they were seen as divine winds sent to protect Japan from its enemies.

However, typhoons were probably not the primary reason for Kublai’s loss. Many flaws may be seen in the ship parts that were discovered there. Estimates suggest that in an effort to break free of Mongol rule, shipyards in China and Korea constructed vessels more suited to river travel than open ocean travel, with much less severe weather. As a result, a lot of ships went down when they should have survived because their hulls weren’t strong enough.

The archipelago was damaged during the invasions. The Hojo regency was losing support as additional taxes were enacted to cover the expense of increasing soldier numbers and conducting defensive preparations. Bands of ronin, or masterless samurai, who had to resort to stealing for survival, only exacerbated the situation and spread unrest throughout the country. To prepare for the worst, the Hojo established a parallel court, thus diluting imperial authority. The emperor’s power was expected to be further diluted by rotating control between the Northern Court and the Southern Court, two branches of the imperial dynasty.

After a few decades of success, in 1331, Emperor Go-Daigo of the Southern Court gained the throne with the goal of toppling the Hojo regents and the shogunate. The Hojo fought against the troops loyal to the emperor but were defeated because of the defection of the Ashikaga family, commanded by Takauji, which led to the dispersion and ultimate rout of the shogunate forces. The Kenmu Restoration, which began in 1333 and lasted just a few years, was an attempt by Emperor Go-Daigo to reinstate imperial rule.

The Kenmu Restoration (1333–1336)

Go-Daigo was able to achieve his primary objective, which was to wrest control of the government back from the shogunate and establish effective rule independent of Kamakura’s troops. However, the Kenmu restoration only lasted a short time because the emperor made a critical tactical error. He believed a sizable portion of the samurai class and the military clans and families referred to as “loyalists” were on his side. In reality, the samurai and loyalist clans joined the insurrection less out of devotion to the emperor and more out of a desire to terminate the Hojo dynasty’s rule. Thus, once the emperor was reinstated as the rightful monarch, Go-Daigo failed to properly thank his friends. He lost the allegiance of the samurai when he failed to compensate them for their service, and the kingdom descended into deeper instability as a result.

In addition, the vast majority of the warrior class was dissatisfied with what they saw as ingratitude, and the great military families were concerned about the efforts of the emperor, who wanted to re-establish a totally civilian authority. There were violent political disputes, particularly between Prince Morinaga, a descendant of the emperor, and Takauji, leader of the Ashikaga clan, who were both vying to position their respective adherents in key positions. As time went on, Takauji proved himself and became the de facto head of the samurai. Finally, in 1335, the King had Morinaga arrested for treason and sent off to Kamakura.

In that year, something out of the ordinary presented him with the chance he needed. Tokiyuki, one of the few people to have lived during the Hojo regency, led a rebellion and briefly took control of Kamakura. The governor appointed by the Ashikaga before his departure had already ordered Morinaga’s death to shift responsibility to the Hojo. Takauji then requested the position of shogun from the emperor in order to quell the uprising. Although Go-Daigo opposed it, Takauji nonetheless fled Kyoto for Kamakura, thereby putting a stop to the Hojo revolt. He told the emperor he had no plans to come back when he was questioned. Secession from the emperor’s rule was obvious at this point, with evidence pointing to Takauji and the Ashikaga having seized control of the Kamakura area.

Almost immediately, the imperial government gathered a force to crush the Ashikaga, while another sent troops to Kamakura to protect the city from attack. Takauji’s brother sent out a series of missives around the land on November 17, 1335, pleading with all samurai to come protect the Ashikaga against the tyranny of the emperor. At the same time, the imperial court asked the samurai to help put down the Ashikaga uprising for good.

Most of the samurai followed Takauji Ashikaga into battle, believing he would be the decisive leader they needed to win the war. The imperial soldiers were vastly outnumbered, but the Ashikaga forces were victorious, and on February 25, 1336, Takauji entered Kyoto, putting a stop to the Kenmu restoration.

The Muromachi period (1337–1573)

Tokugawa Ieyasu selected Takauji Ashikaga as Shogun in 1337, but not before a contentious and lengthy argument that lasted over a year. By 1573, the Ashikaga shogunate remained in power. The third Ashikaga shogun relocated the capital of Japan from Nara to Kyoto in 1378, ushering in the Muromachi period. The relocation was made to keep imperial authority much more tightly under control. Although the Kamakura shogunate did not completely eliminate imperial authority, the Ashikaga shattered the notion that the emperor should govern directly, thereby making the role of shogun essential to the empire’s proper administration.

At the beginning of the Muromachi period, the position of governor became synonymous with extensive powers, with those who held it having almost full authority over the lands they ruled, answering only to the shogun, whereas under the Kamakura shogun, the governor was merely an agent who acted on behalf of the shogun. These lords, who were called daimyos, quickly overtook the shogun court as the most powerful people in the government of the kingdom.

Another step the Ashikaga took to consolidate their influence at the imperial level was to unify the formerly fractured Imperial Court under the Hojo regency in 1392. Finally, the Ashikaga’s fall allowed the daimyos to directly back some of the candidates for the imperial succession, resulting in the election to the throne of emperors who supported the daimyos’ interests, often at the cost of the shogun’s. The Ashikaga shogunate’s power and reputation began to dwindle with the reign of the fourth shogun.

The Ashikaga stayed in power officially until 1573, although they began showing indications of decadence even before then. In 1467, an argument over Japan’s emperor’s line of succession sparked the Ônin War, which lasted from 1467 to 1477 and ushered in a new period of instability in the country. The nation descended into anarchy during a period of civil war in which every family and clan fought for its own goals.

This troubled period is known as Sengoku-jidai, the age of warring countries.

In 1477, Japan was in shambles. Even though the Ônin War had ended not long before, there was still a lot of unrest. The Ashikaga dynasty, which had ruled Japan in the name of the Emperor as Seishi Taishogun since 1337, was beginning to lose power and was unable to stop the rising warfare among the country’s many noble families and clans. Slowly but surely, Japan disintegrates, plunging into the Sengoku-jidai (Warring States period)—one of the worst chapters in the nation’s history. A time of tremendous change and turmoil.

Nanban and gunpowder

In 1543, a typhoon off the coast of Tanegashima, in southern Japan, kidnapped a ship full of Portuguese sailors and brought them to the Japanese islands. There was a profound shock since the Japanese had never before had any meaningful interaction with European cultures. The Portuguese were referred to as “Nanban” by the Japanese. This term translates to “Southern Barbarians.”

Despite an embargo placed by the Emperor of China in retribution for Japanese piracy, the Portuguese started importing Chinese commodities, notably silk, into Japan within a few years. Eventually, business picked up speed. The port of Nagasaki opened as a commercial station in 1571, and commerce with the Portuguese increased rapidly. Shortly later, in 1578, the daimyo of the Sumitada clan requested Portuguese aid in fending off an assault on the daimyo, and in return, the port was permanently surrendered to the Jesuits.

To Japan next came the Dutch in the year 1600. The competition with the Portuguese for control of commerce with the Land of the Rising Sun was severe.

There were two key shifts that the introduction of Westerners to Japan brought about. One of the causes was technical. Gunpowder’s use in Japanese military operations was nascent in 1543. The intention behind this seemingly minor innovation was to dramatically shift the power dynamic. Suddenly, families armed with Portuguese arquebuses could compete with their more formidable neighbors.

The availability of such weapons also contributed to the escalation of hostilities. Fighting broke out on the southern island of Kyushu when the Portuguese arrived, and it wasn’t until later that harquebuses became commonplace across the archipelago. They were dubbed Tanegashima after the island where the Nanban had their first encounter. By 1560, harquebuses were widely used in warfare.

The harquebuses were not the only thing the Westerners brought with them, though; the Christian faith was also a major contributor to tensions. Six years after the first meeting, Nagazaki built its first church. The founder of the Jesuits, the Catholic Church’s missionary arm, set his sights on Japan in an effort to win over the local population. In under 30 years, the majority of the daimyo in Kyushu and more than 130,000 other Japanese were converted.

Christianity flourished across Japan, from the lowest of the low to the highest of the high, despite the social boundaries that existed between the various classes. While some daimyo were willing to accept Buddhism without investigation, others were suspicious of the new faith, believing it was being utilized by the Nanban to penetrate Japan. Christian and non-Christian daimyos began fighting with one another.

Gekokujo: The powerful are defeated by the humble

Unique occurrences were taking place in the midst of the clan battles that were ripping the nation apart. The ancient, strong, and respected clans, led by clan chiefs who, under the Japanese social structure, were the lords of their vassals, were slowly losing ground to the young, dynamic clans and their ambitious chiefs. The old order had been shattered by feuding among the families that used to rule, and now people who had to bow to the will of the powerful families during times of calm find themselves vying for control. Gekokujo, which means “the humble defeat the powerful,” was the term used to describe this trend.

Therefore, the battle intensifies rapidly as fighting occurs not only between clans but also within clans, as different families and family branches strive to take over the others. The commoners and peasants in the region of Echigo, located north of Kyoto on the coast of the Sea of Japan, rise up and declare their independence with the aid of the small nobility and ronins, samurai left without a weapon by the war. This occurs as a result of the religious movement known as Ikkō-ikki (Buddhist school of the “Pure Land”).

By uniting peasants, ronins, and clerics, the people of Iga (the valley of the skull) were able to break free of the control of the feudal lords and form a defense league (ikki) to protect themselves against outsiders. The area became well known for the ninja clans that inhabited it. In a nutshell, this phenomenon hastened the fragmentation of the kingdom into warring groups, but it also presented a once-in-a-lifetime chance to break the societal inertia that had contributed to the decline of the Ashikaga dynasty.

The Unification of Japan: Oda Nobunaga (1534–1582)

Three ambitious and talented men arose from this time of turmoil to unite Japan under a single flag once again. The first of them took was the head of the tiny Oda clan in central Japan’s Owari prefecture in 1551. His name was Nobunaga Oda.

The Oda clan was in a precarious position at the time; they were vassals to provincial ruler Shiba Yoshimune, and they were also deeply divided. This was possible thanks to the backing of the latter and one of his younger brothers, Oda Nobumitsu, and in spite of the resistance of Nobutomo, another of his brothers, who had Yoshimune assassinated in an effort to cut Nobunaga off from his support. With the use of Yoshimune’s son as a stooge, Nobunaga was able to eliminate his brother and competitor, Kiyosu, and form an alliance with the strong Imagawa clan. Although it took him eight years and the death of one of his brothers, Oda Nobunaga eventually unified the region of Owari in 1559.

The next year, Nobunaga faced off against the Imagawa, who had gathered 25,000 troops to march on Kyoto, compared to 3,000. Against the odds and the advice of his counselors, Nobunaga assaulted the Imagawa soldiers, sowing havoc in the ranks of his foes with the help of straw dummies and a miraculous storm. The Imagawa general was slain at Okehazama. As a result, the Imagawa rapidly fell from power, and in 1561, Nobunaga allied himself with the Mitsudaira, one of the Imagawa’s former vassal families.

Between 1561 to 1567, he led an endeavor to seize control of the adjacent province of Mino by convincing the vassals of the Saito clan to defect from their lord and eventually launched a blitzkrieg that quickly and easily defeated the Saito. Following this victory, his new personal seal reads “Tenka Fubu,” which translates to “The world by force of arms.”

Ashikaga Yoshiaki became the 15th shogun of the Ashikaga clan when Nobunaga marched on Kyoto at the behest of the Ashikaga family in 1568 and promptly drove the Miyoshi clan out of the city. Nobunaga started limiting the shogun’s authority very immediately, enhancing his own, and signaling to the daimyo that he meant to employ the shogun as a puppet.

The move was too much for Nobunaga’s enemies to handle. The Asai and the Ikkō-ikki, under the leadership of the Asakura, the Oda’s previous overlords, launched a coordinated attack on the clan, killing many members. After a long period of resistance, the Oda were able to crush the Asai and Asakura forces in the battle of Anegawa with the support of their allies, the Tokugawa (previously Mitsudaira). As a result, Nobunaga, who was well-known at the period for his Christian views, launched an assault on the Buddhists who had risen up against him. In 1571, he besieged the Nagashima castle and burned down the Enryaku-ji shrine. Although he lost several thousand men and two brothers in the battle against the Ikkō-ikki Buddhists, he was able to quell the uprising by burning the castle in 1574.

At the Battle of Nagashino in 1574, Nobunaga and the Tokugawa attacked Takeda territory, wiping out the entire Takeda army, owing in part to their ingenious employment of arquebusiers, who were organized in a triple line of fire to enable continuous firing. This loss would prove fatal to Takeda.

After three years of consolidation, Nobunaga’s holdings were threatened by the Mori in the west, who had broken the naval siege of the last remaining Buddhist fortress at Igashiyama, prompting Nobunaga to send his lieutenant, the future Toyotomi Hideyoshi, to fight the Mori. In 1577, the Uesugi clan, commanded by Uesugi Kenshin, assembled the northern clans to launch an assault against the Oda, who were soundly defeated in the ensuing battle at Tedorigawa. The death of Kenshin was the only thing that finally broke apart the second anti-Oda alliance.

Half of Japan was under Nobunaga’s authority by 1582, and he had taken Kyoto. As the Mori conquest pressed forward, no northern tribes were able to put up a real fight. Mitsuhide, one of Nobunaga’s lieutenants, staged a coup d’état while the general was on his way to the western front. To cast doubt on the succession, Mitsuhide had his forces surround the Honno-ji temple where Nobunaga was residing and assassinate him and his oldest son.

Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1536/37–1598)

The situation became murky after Nobunaga’s death. Hashiba Hideyoshi intervened when a return to anarchy seemed imminent. Originally from the peasant class, this former lieutenant of Nobunaga began his service to the shogun as a sandal carrier.

Nobunaga was supposed to have taken note of his sharp-witted retainer at Okehazama. He sent him in 1564 to win over Saito clan deserters for the Oda side. The battle of Inabayama was won by Hideyoshi in 1567 owing to his plan to flood the valley where the fortress was located. After Nobunaga appointed Hideyoshi daimyo of a fief in northern Omi in 1573, the latter remained a devoted servant of the shogun and fought the Mori clan’s battle between 1577 and 1582.

Hideyoshi swiftly signed a peace treaty with the Mori after hearing of Mitsuhide’s betrayal and Nobunaga’s death, and then turned his men on the traitors in the battle of Yamazaki. Once his master was avenged, it was time to organize Nobunaga’s succession at the meeting with Kiyosu. After his passing, his oldest son left numerous potential successors, including Oda Nobutaka, Oda Nobukatsu, and Oda Hidenobu. Hideyoshi sided with the latter, aided by two of the three Oda clan counselors. With two swift triumphs, he silenced Shibata Katsuie, Nobutaka’s attorney, and kept the Tokugawa from actively supporting Nobukatsu.

Hideyoshi started consolidating power over the Oda clan when his candidate was established as head of the clan in 1583. He accomplished this by building Osaka Castle. During this time of quiet, the Fujiwara regent family formally adopted him, giving him the name Toyotomi and the title of Kampaku, (“regent”).

Hideyoshi, confident in his superiority, went out to expand his territory to the south, eventually seizing all of southern Honshu and displacing the Chokosabe clan from Shikoku. He arrived in Kyushu in 1587 and, firmly opposed to the spread of Christianity, ordered all missionaries off the island. As a means of preventing the emergence of new leagues (or ikki), he instituted a ban on weapon possession among commoners and peasants and launched an operation that became known as the “sword hunt.” After consolidating his power in the south, Hideyoshi shifted his focus to the east and, in the Siege of Odawara, put an end to the Hojo clan, the last major autonomous clan in Japan. Then, he gave Tokugawa Ieyasu their Kanto territory in exchange for submission, and the latter accepted. At this point, Hideyoshi was able to call himself the ruler of a united Japan.

Unhappily, he did not stop there with his aspirations. The notion of conquering Ming China crossed his mind when he had finally consolidated his power in Korea (Joseon at that time). As a result of the vassal governors of Korea refusing his free-passage agreements in August 1591, the Emperor of China began making preparations to attack Korea.

In April 1592, Japanese forces invaded Korea, rapidly capturing Seoul without any resistance. They then started dividing and conquering the country’s important locations before China could respond. By the spring of 1593, only four months after they had set out, they had begun forcibly opening a path to Manchuria. The Japanese were pushed back to Seoul, where their offensives were delayed by a counterattack by the Chinese.

Hideyoshi’s stability was shaken by the disaster of the Korean expedition, and the birth of his first son the same year sparked a succession dispute with his nephew. Meanwhile, the harsh persecution of Christians added fuel to the fire. Hideyoshi died on September 18, 1598, as a result of the devastating effects of a plague pandemic that had broken out across the kingdom. Once again, Japan was left without a strong leader.

The Tokugawa Leyasu period (1543–1616)

Tokugawa Ieyasu, a longstanding ally of the Oda, had taken up arms against Toyotomi Hideyoshi since the latter was not an ally but a competitor. As far back as 1584, when the Tokugawa supported Oda Nobukatsu over Hideyoshi’s candidate in the succession to Nobunaga, the Tokugawa had been at odds with Hideyoshi and his kin. Ieyasu’s son became Hideyoshi’s adopted child when the two leaders settled their differences and established a united government.

While Hideyoshi consolidated power elsewhere in Japan, he made the Hojo stronghold of Kanto available to the Tokugawa in 1588. Quickly agreeing, Ieyasu saw the chance to extend his empire (from 5 to 8 provinces), while Hideyoshi wanted to undermine his competitor by relocating him to an area he did not control. Ieyasu won over the previous Hojo clan members and started constructing a new domain in Edo while patiently waiting for his opportunity.

After Hideyoshi appointed him and four other counselors as regents for his son Hideyori, he served in this capacity until Hideyoshi’s death in 1598. After Maeda Toshiie, the most revered of the five regents, was killed, Ieyasu spent a year forging alliances with Hideyoshi’s erstwhile opponents and then marched on Osaka Castle, where Hideyori was hiding.

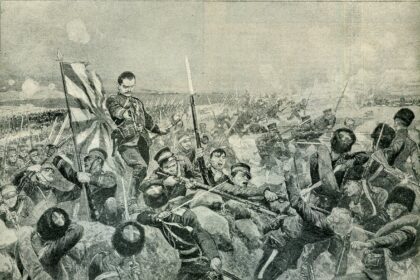

Ishida Mitsunari rallied the other three regents to stand against him. It didn’t take long for the western army to become a clan that supported Hideyoshi and the eastern army to establish a clan that supported the Tokugawa clan. During the greatest battle in Japanese history in June of 1600, the Tokugawa clan marched north against the Uesugi clan and then west to counter the army marching to Fushimi, dividing its forces under the command of his son Hidetada. However, this secondary force fell behind along the Tokaido route and was therefore not present.

The Battle of Sekigahara took place on the 21st of October, 1600, and included around 160,000 troops. The battle was intense, but the Tokugawa ultimately broke through the western army’s right flank, resulting in a widespread defeat that allowed them to seize control of Japan and wipe out their competitors simultaneously. On April 24, 1603, after consolidating and solidifying his power, he was made shogun, marking the commencement of the last Japanese shogunate, which would continue for almost 250 years.

Bibliography:

- Gérard Siary, Histoire du Japon : des origines à nos jours, Tallandier, 2020.

- Hudson, Mark (2009). “Japanese Beginnings”, p. 15 In Tsutsui, William M. (ed.). A Companion to Japanese History. Malden MA: Blackwell. ISBN 9781405193399.

- Watanabe Hiroshi, A History of Japanese Political Thought, 1600-1901, Tokyo, International House of Japan, 2012, 543 p. (ISBN 978-4-924971-32-5).

- uzmin, Y.V. (2006). “Chronology of the Earliest Pottery in East Asia: Progress and Pitfalls”. Antiquity. 80 (308): 362–371. doi:10.1017/s0003598x00093686. S2CID 17316841.

- Haruo Shirane, Tomi Suzuki et David Lurie, The Cambridge History of Japanese Literature, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, mars 2016, 865 p. (ISBN 978-1-107-02903-3).

- Hammer, Michael F.; Karafet, Tatiana M.; Park, Hwayong; Omoto, Keiichi; Harihara, Shinji; Stoneking, Mark; Horai, Satoshi (2006). “Dual origins of the Japanese: Common ground for hunter-gatherer and farmer Y chromosomes”. Journal of Human Genetics. 51 (1): 47–58. doi:10.1007/s10038-005-0322-0. PMID 16328082.

- Jonah Salz, A History of Japanese Theatre, Cambridge/New York, Cambridge University Press, juin 2016, 550 p. (ISBN 978-1-107-03424-2).

- Turnbull, Stephen (1998). The Samurai Sourcebook. Cassell & Co. p. 200. ISBN 1854095234.

- Pierre François Souyri, Nouvelle Histoire du Japon, Paris, Perrin, septembre 2010, 627 p. (ISBN 978-2-262-02246-4, OCLC 683200336).