The Mythical First Emperor Ascended to the Throne – February 11, 660 BC

Information found in ancient Japanese mythological and historical chronicles has allowed for the establishment of the date of the ascension to the throne of the mythical first emperor Jimmu, from whom the imperial family of Japan is said to originate. On this day, Jimmu, a descendant of the sun goddess Amaterasu, went through an enthronement ceremony in the capital he founded, in a place called Kashihara.

- The Mythical First Emperor Ascended to the Throne – February 11, 660 BC

- The First Legal Code – 701

- The Founding of Japan’s First Permanent Capital – 710

- Attempted Soft Coup – 769

- Establishing Control Over the Imperial Family – 866

- Cessation of Official Relations Between Japan and China – 894

- Introduction of the Mechanism of Abdication – 1087

- Establishment of Dual Governance in Japan – 1192

- Attempted Mongol Invasion of Japan – 1281

- Schism within the Imperial House – 1336

- Beginning of the Period of Feudal Fragmentation – 1467

- Arrival of the First Europeans – 1543

- The Beginning of the Unification of Japan – 1573

- Attempts at Military Expansion on the Mainland – 1592

- Completion of Japan’s Unification – October 21, 1600

- The Edict on National Isolation – 1639

- The Beginning of Japan’s Cultural Flourishing – 1688

- Meiji Restoration and Modernization of Japan – 1868

- Surrender in World War II and the Beginning of American Occupation – September 2, 1945

- The Beginning of Post-War Reconstruction of Japan – 1964

Naturally, there was no question of statehood in Japan at that time, nor of the existence of Jimmu or the Japanese people themselves. The myth was integrated into everyday life and became a part of history. In the first half of the 20th century, the day of Jimmu’s enthronement was a national holiday, during which the reigning emperor participated in prayers for the well-being of the country. In 1940, Japan celebrated 2,600 years since the founding of the empire.

Due to a complex foreign political situation, it was necessary to abandon plans for hosting the Olympic Games and the World Expo. The symbol of the latter was to be Jimmu’s bow and a golden kite that appeared in the myth:

“The army of Jimmu fought the enemy but could not defeat them. Suddenly, the sky was covered with clouds, and hail began to fall. Then, a miraculous golden kite appeared and perched on the upper edge of the imperial bow. The kite glowed and sparkled like lightning. The enemies saw this, were thrown into complete confusion, and lost all will to fight.”

Nihongi : Chronicles of Japan from the Earliest Times to A.D. 697 – Link

After Japan’s defeat in World War II in 1945, references to Jimmu became rare and cautious due to his strong association with militarism.

The First Legal Code – 701

In the early 8th century, Japan continued its active efforts to form institutions of power and establish norms governing relations between the state and its subjects. The Japanese state model was based on the Chinese one. Japan’s first legal code, compiled in 701 and enacted in 702, was called “Taihō Code.”

Its structure and specific provisions were based on Chinese legal thought, although there were significant differences. For example, criminal law norms in Japanese legislation were developed with much less precision, reflecting the cultural peculiarities of the Japanese state, which preferred to delegate the responsibility of punishing offenders and replace physical punishment with exile, to avoid ritual impurity (kegare) caused by death. Thanks to the Taihō Code, historians refer to 8th-9th century Japan as a “state founded on laws.” Despite some provisions of the code becoming obsolete even at the time of its creation, it formally remained in force until the adoption of Japan’s first constitution in 1889.

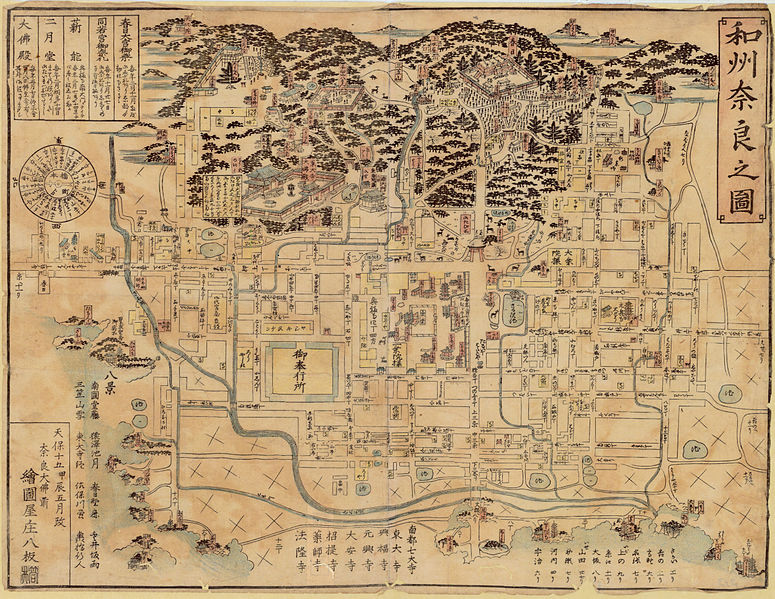

The Founding of Japan’s First Permanent Capital – 710

The development of statehood required the concentration of the court elite and the establishment of a permanent capital. Until that time, each new ruler built a new residence, as staying in a palace defiled by the death of a previous ruler was considered dangerous. However, by the 8th century, the model of a nomadic capital no longer matched the scale of the state. Nara became Japan’s first permanent capital.

The site for its construction was chosen based on geomantic principles of spatial protection: a river to the east, a pond and plains to the south, roads to the west, and mountains to the north. These principles would later be used for selecting sites for the construction of cities and aristocratic estates.

Nara was laid out as a rectangle covering 25 square kilometers, copying the structure of the Chinese capital, Chang’an. Nine vertical and ten horizontal streets divided the area into equal blocks. The central Suzaku Avenue stretched from south to north, ending at the gates of the imperial residence. The title of the Japanese emperor, Tennō, also referred to the Pole Star, positioned immovably in the northern sky. Like the star, the emperor surveyed his domains from the north of the capital. The districts adjacent to the palace complex were the most prestigious; exile from the capital to the provinces could be a severe punishment for an official.

Attempted Soft Coup – 769

Political struggle in Japan took various forms during different historical periods, but a common feature was the absence of attempts to seize the throne by those outside the imperial family. The sole exception was the monk Dōkyō. Coming from the impoverished provincial Yuge family, he rose from being an ordinary monk to a powerful ruler of the country. Dōkyō’s rise was particularly surprising, given that the social structure of Japanese society strictly determined a person’s fate. Ancestry played a decisive role in the assignment of court ranks and government positions. Dōkyō joined the court monk staff in the early 50s.

Monks of that time were not only trained in Chinese literacy, which was necessary for reading Buddhist texts translated from Sanskrit in China, but also possessed other useful skills, particularly in medicine. Dōkyō earned a reputation as a skilled healer, which likely led to his being sent to the ailing former Empress Kōken in 761. Not only did he manage to cure the former empress, but he also became her closest advisor.

According to the collection of Buddhist legends “Nihon Ryōiki,” Dōkyō shared a pillow with the empress and ruled the empire. Kōken ascended the throne again under the name Shōtoku and introduced new positions specifically for Dōkyō, which were not provided for by law and granted him extensive powers.

The empress’s trust in Dōkyō was boundless until 769 when he, using faith in prophecies, declared that the god Hachiman from the Usa shrine wished for Dōkyō to become the new emperor. The empress demanded confirmation from the oracle, and this time Hachiman declared: “From the beginning of our state to this day, it has been determined who should be the ruler and who should be the subject. Never has a subject become the ruler. The throne of the sun in the heavens must be inherited by the imperial house.

The unrighteous should be exiled.” After the empress’s death in 770, Dōkyō was stripped of all ranks and positions and expelled from the capital. The cautious attitude toward the Buddhist church persisted for several decades. It is believed that the transfer of the capital from Nara to Heian, completed in 794, was partly motivated by the state’s desire to free itself from the influence of Buddhist schools, as none of the Buddhist temples were moved from Nara to the new capital.

Establishing Control Over the Imperial Family – 866

The most effective tool for political struggle in traditional Japan was establishing kinship ties with the imperial family and holding positions that allowed one to dictate their will to the ruler. The Fujiwara family excelled in this more than others, supplying brides to emperors for a long time and, from 866, securing a monopoly on appointments to the positions of regents (Sesshō) and, slightly later (from 887), chancellors (Kampaku). In 866, Fujiwara no Yoshifusa became the first regent in Japanese history not of imperial descent.

Regents acted on behalf of underage emperors, who lacked their own political will, while chancellors represented adult rulers. They not only controlled current affairs but also determined the order of succession to the throne, forcing the most active rulers to abdicate in favor of minor heirs, who typically had kinship ties to the Fujiwara.

The regents and chancellors reached the height of their power by 967. The period from 967 to 1068 is known in historiography as the “Sekkan Period”—the “Era of Regents and Chancellors.” Over time, they lost influence, but their positions were not abolished. Japanese political culture is characterized by the nominal preservation of old institutions of power while creating new ones that duplicate their functions.

Cessation of Official Relations Between Japan and China – 894

Foreign contacts of ancient and early medieval Japan with continental powers were limited. They mainly consisted of exchanges of embassies with the states of the Korean Peninsula, the Bohai state, and China. In 894, Emperor Uda summoned officials to discuss the details of the next embassy to the Middle Kingdom. However, the officials advised against sending an embassy at all.

Influential politician and renowned poet Sugawara no Michizane particularly insisted on this. The main argument was the unstable political situation in China. From this time, official relations between Japan and China ceased for a long period. In the historical perspective, this decision had many consequences. The absence of direct cultural influence from abroad led to a need to rethink the borrowings made earlier and to develop uniquely Japanese cultural forms.

This process was reflected in almost all aspects of life, from architecture to fine literature. China ceased to be considered a model state, and later Japanese thinkers would often point to the political instability on the continent and the frequent change of ruling dynasties to justify Japan’s uniqueness and superiority over the Middle Kingdom.

Introduction of the Mechanism of Abdication – 1087

A system of direct imperial governance is not typical for Japan. Real politics are conducted by the emperor’s advisors, regents, chancellors, and ministers. This, on the one hand, strips the reigning emperor of many powers, but on the other hand, makes it impossible to criticize him personally. The emperor usually engages in the sacred governance of the state. There were exceptions, however.

One of the ways emperors regained political authority was through the mechanism of abdication, which allowed a ruler to govern without being bound by ritual obligations when transferring power to a loyal heir. In 1087, Emperor Shirakawa abdicated in favor of his eight-year-old son Horikawa, then took monastic vows, but continued to manage court affairs as an ex-emperor. Until his death in 1129, Shirakawa dictated his will to both the reigning emperors and the regents and chancellors from the Fujiwara clan.

This form of governance by abdicated emperors became known as insei — “rule from the cloister.” Despite the reigning emperor holding sacred status, the ex-emperor was considered the head of the family, and according to Confucian teachings, his will had to be obeyed by all junior family members. The Confucian type of hierarchical relations was also prevalent among the descendants of Shinto deities.

Establishment of Dual Governance in Japan – 1192

In traditional Japan, military professions and forceful methods of conflict resolution were not particularly prestigious. Civil officials, who were literate and able to compose poetry, were preferred. However, in the 12th century, the situation changed. Representatives of provincial military houses, particularly the Taira and Minamoto, emerged on the political scene with significant influence. The Taira achieved what was previously impossible — Taira no Kiyomori occupied the position of chief minister and managed to place his grandson on the imperial throne.

By 1180, dissatisfaction with the Taira from other military houses and members of the imperial family reached its peak, leading to a protracted military conflict known as the “Genpei War.” In 1185, the Minamoto, under the leadership of the talented administrator and ruthless politician Minamoto no Yoritomo, achieved victory.

However, instead of restoring power to the court aristocrats and members of the imperial family, Minamoto no Yoritomo systematically eliminated his competitors, established himself as the sole leader of the military houses, and in 1192 received the title of Seii Taishogun — “Great General who Subdues the Barbarians” — from the emperor.

From this time until the Meiji Restoration in 1867–1868, a system of dual governance was established in Japan. Emperors continued to perform rituals, while the shoguns, as military rulers, conducted actual political governance, managed foreign relations, and often interfered in the internal affairs of the imperial family.

Attempted Mongol Invasion of Japan – 1281

In 1266, Kublai Khan, who had conquered China and founded the Yuan Dynasty, sent a message to Japan demanding recognition of Japan’s vassal status. He received no response. Later, several similar messages were sent without success. Kublai Khan began preparing a military expedition to the shores of Japan, and in the fall of 1274, the Yuan fleet, which included Korean units and totaled 30,000 men, pillaged the islands of Tsushima and Iki and reached Hakata Bay.

The Japanese forces were inferior in both numbers and weaponry, but direct military confrontation was largely avoided. A storm scattered the Mongol ships, forcing them to retreat. Kublai Khan made a second attempt to conquer Japan in 1281. The military campaign lasted just over a week before events repeated: a typhoon destroyed much of the massive Mongol fleet and thwarted plans to subjugate Japan.

These campaigns are linked to the emergence of the concept of kamikaze, which literally means “divine wind.” To the modern person, kamikaze is primarily associated with suicide pilots, but the term is much older. According to medieval beliefs, Japan was the “land of the gods.” Shinto deities, who inhabited the archipelago, protected it from external harmful influences. This was confirmed by the “divine wind” that twice prevented Kublai Khan from conquering Japan.

Schism within the Imperial House – 1336

Traditionally, it is believed that the Japanese imperial line has never been interrupted, which allows us to speak of the Japanese monarchy as the oldest in the world. However, there were periods in history when the ruling dynasty experienced schisms. The most serious and prolonged crisis, during which two sovereigns ruled Japan simultaneously, was triggered by Emperor Go-Daigo. In 1333, the position of the Ashikaga military house, led by Ashikaga Takauji, strengthened. The emperor sought their assistance in his struggle against the shogunate.

In return, Takauji desired the position of shogun and aimed to control Go-Daigo’s actions. The political struggle turned into open military conflict, and in 1336, Ashikaga’s forces defeated the imperial army. Go-Daigo was forced to abdicate in favor of a new emperor favored by Ashikaga. Unwilling to accept these circumstances, Go-Daigo fled to Yoshino in the Yamato Province, where he founded the so-called Southern Court. Until 1392, two centers of power existed in Japan — the Northern Court in Kyoto and the Southern Court in Yoshino.

Both courts had their own emperors and appointed their own shoguns, making it virtually impossible to determine the legitimate ruler. In 1391, Shogun Ashikaga Yoshimitsu proposed a truce to the Southern Court, promising that henceforth, the throne would alternate between representatives of the two lines of the imperial family. The proposal was accepted, ending the schism, but the shogunate did not keep its promise: the throne was occupied by representatives of the Northern Court. Historically, these events were perceived very negatively.

For example, in history textbooks written during the Meiji period, the Northern Court was often ignored, and the period from 1336 to 1392 was referred to as the Yoshino Period. Ashikaga Takauji was portrayed as a usurper and an enemy of the emperor, while Go-Daigo was described as an ideal ruler. The schism within the ruling house was seen as an unacceptable event, one that should not be remembered unnecessarily.

Beginning of the Period of Feudal Fragmentation – 1467

Neither the shoguns from the Minamoto dynasty nor those from the Ashikaga family were sole rulers who commanded all the military houses of Japan. Often, the shogun acted as an arbitrator in disputes arising between provincial warriors. Another prerogative of the shogun was the appointment of military governors in the provinces. These positions became hereditary, which contributed to the enrichment of certain clans. The rivalry between military houses for positions, as well as the struggle for the right to be called the head of a clan, did not bypass the Ashikaga family.

The shogunate’s inability to resolve accumulated contradictions led to major military clashes that lasted 10 years. The events of 1467–1477 are known as the “Ōnin-Bunmei War.” Kyoto, then the capital of Japan, was almost completely destroyed, the Ashikaga shogunate lost its authority, and the country was left without a central government. The period from 1467 to 1573 is called the “Era of Warring Provinces.” The absence of a real political center and the strengthening of provincial military houses, which began issuing their own laws and introducing new systems of ranks and positions within their domains, led to a period of feudal fragmentation in Japan.

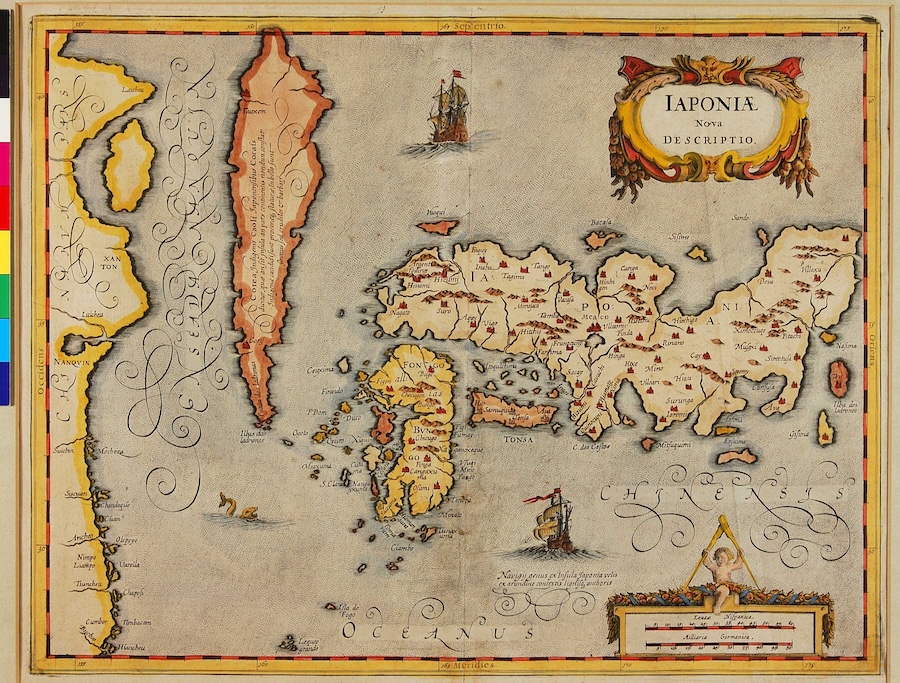

Arrival of the First Europeans – 1543

The first Europeans to set foot on Japanese soil were two Portuguese traders. On the 25th day of the 8th month in the 12th year of Tenbun (1543), a Chinese junk with two Portuguese on board was driven to the southern tip of the island of Tanegashima. The negotiations between the newcomers and the Japanese were conducted in writing. Japanese officials could write in Chinese, but they did not understand the spoken language.

The characters were drawn directly in the sand. It was established that the junk had been accidentally driven ashore by a storm, and these strange people were traders. Soon they were received at the residence of Tokitaka, the ruler of the island. Among the various exotic items they brought were muskets. The Portuguese demonstrated the capabilities of firearms. The Japanese were struck by the noise, smoke, and firepower: the target was hit from a distance of 100 paces. Two muskets were immediately purchased, and Japanese blacksmiths were tasked with setting up their own firearm production.

By 1544, several gunsmith workshops were operating in Japan. Contacts with Europeans soon intensified. Besides weapons, they spread Christian teachings throughout the archipelago. In 1549, Jesuit missionary Francis Xavier arrived in Japan. He and his followers engaged in active proselytizing, converting many Japanese lords — daimyo — to Christianity. The nature of Japanese religious consciousness suggested a calm attitude toward faith. Adopting Christianity did not necessarily mean renouncing Buddhism or the belief in Shinto deities. Later, Christianity was banned in Japan under the threat of the death penalty, as it undermined state authority and led to unrest and uprisings against the shogunate.

The Beginning of the Unification of Japan – 1573

Among the historical figures of Japan, perhaps the most recognizable are the military leaders known as the Three Great Unifiers: Oda Nobunaga, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, and Tokugawa Ieyasu. Their actions are believed to have overcome feudal fragmentation and unified the country under a new shogunate, founded by Tokugawa Ieyasu. The unification began with Oda Nobunaga, an outstanding military commander who managed to subdue many provinces thanks to the talents of his generals and the skilled use of European weapons in battle.

In 1573, he expelled Ashikaga Yoshiaki, the last shogun of the Ashikaga dynasty, from Kyoto, making it possible to establish a new military government. According to a proverb from the 17th century: “Nobunaga kneaded the dough, Hideyoshi baked the cake, and Ieyasu ate it.” Neither Nobunaga nor his successor, Hideyoshi, were shoguns. It was only Tokugawa Ieyasu who obtained the title and secured its hereditary transfer, but this would have been impossible without the actions of his predecessors.

Attempts at Military Expansion on the Mainland – 1592

Toyotomi Hideyoshi was not of noble birth, but his military achievements and political intrigue allowed him to become the most influential person in Japan. After Oda Nobunaga’s death in 1582, Hideyoshi dealt with General Akechi Mitsuhide, who betrayed Oda. Revenge for his lord greatly increased Toyotomi’s authority among his allies, who rallied under his command. He managed to subdue the remaining provinces and strengthen his ties not only with the military houses but also with the imperial family.

In 1585, he was appointed as Kampaku (Chancellor), a position traditionally held only by aristocrats from the Fujiwara clan. His legitimacy was now based not only on arms but also on the Emperor’s will. After unifying Japan, Hideyoshi attempted external expansion on the mainland. The last time Japanese troops participated in mainland military campaigns was in 663. Hideyoshi planned to conquer China, Korea, and India. However, these plans were not realized.

The events from 1592 to 1598 are known as the Imjin War, during which Toyotomi’s forces fought unsuccessful battles in Korea. After Hideyoshi’s death in 1598, the expeditionary corps was urgently recalled to Japan. Japan would not attempt any further military expansion on the mainland until the end of the 19th century.

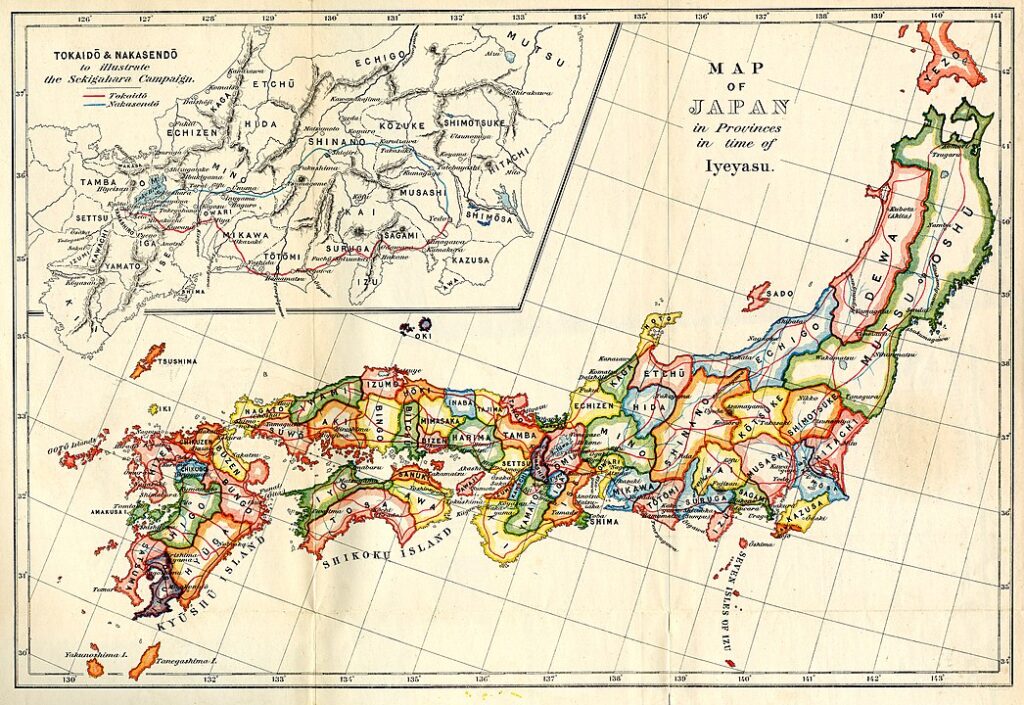

Completion of Japan’s Unification – October 21, 1600

The founder of the third and final shogunate dynasty in Japanese history was the military leader Tokugawa Ieyasu. He was granted the title of Seii Taishogun by the Emperor in 1603. Tokugawa secured his position as the head of the military houses through his victory at the Battle of Sekigahara on October 21, 1600. All military houses that fought on Tokugawa’s side were called fudai daimyo, while his opponents were called tozama daimyo.

The former received fertile lands and the opportunity to hold government positions in the new shogunate. The lands of the latter were confiscated and redistributed. The tozama daimyo were also excluded from participating in government, leading to dissatisfaction with Tokugawa’s policies. Members of the tozama daimyo would later become the main force of the anti-shogunate coalition that brought about the Meiji Restoration in 1867-1868. The Battle of Sekigahara marked the end of Japan’s unification and paved the way for the establishment of the Tokugawa shogunate.

The Edict on National Isolation – 1639

The period of Tokugawa shoguns’ rule, also known as the Edo period (1603-1867) after the name of the city (Edo, now Tokyo) where the shogunate’s residence was located, was characterized by relative stability and the absence of serious military conflicts. This stability was partly achieved through the rejection of foreign contacts. Beginning with Toyotomi Hideyoshi, Japanese military rulers implemented a consistent policy to limit European activities on the archipelago: Christianity was banned, and the number of ships allowed to enter Japan was restricted.

Under the Tokugawa shoguns, the process of national isolation was completed.

In 1639, an edict was issued prohibiting any Europeans, except for a limited number of Dutch traders, from entering Japan. The year before, the shogunate had faced difficulties in suppressing a peasant uprising in Shimabara, which was led under Christian slogans. From then on, Japanese were also forbidden from leaving the archipelago. The seriousness of the shogunate’s intentions was confirmed in 1640 when the crew of a ship from Macau, which had arrived in Nagasaki to renew relations, was arrested. Sixty-one people were executed, and the remaining 13 were sent back. The policy of self-isolation would last until the mid-19th century.

The Beginning of Japan’s Cultural Flourishing – 1688

During the Tokugawa shogunate’s rule, urban culture and entertainment flourished. The peak of creative activity occurred during the Genroku era (1688-1704). It was during this time that the playwright Chikamatsu Monzaemon, later called the “Japanese Shakespeare,” the poet Matsuo Basho, a reformer of the haiku genre, and the writer Ihara Saikaku, known to Europeans as the “Japanese Boccaccio,” created their works. Saikaku’s works were secular in nature and often humorously depicted the everyday life of townspeople. The Genroku years are considered the golden age of Kabuki theater and the Bunraku puppet theater. This period also saw the active development of crafts as well as literature.

Meiji Restoration and Modernization of Japan – 1868

The end of the military houses’ rule, which lasted over six centuries, came during the events known as the “Meiji Restoration.” A coalition of warriors from the Satsuma, Choshu, and Tosa domains forced Tokugawa Yoshinobu, the last shogun in Japanese history, to return supreme power to the Emperor. This marked the beginning of Japan’s active modernization, accompanied by reforms in all areas of life. Western ideas and technologies were quickly adopted. Japan embarked on a path of Westernization and industrialization.

The reforms during Emperor Meiji’s reign were carried out under the slogan “Japanese spirit, Western technology,” reflecting the specifics of how the Japanese incorporated Western ideas. Universities were opened, compulsory elementary education was introduced, the army was modernized, and a Constitution was adopted. During Emperor Meiji’s reign, Japan became an active political player: it annexed the Ryukyu Archipelago, colonized Hokkaido, won the Sino-Japanese and Russo-Japanese wars, and annexed Korea. After the restoration of imperial power, Japan participated in more military conflicts than during the entire period of the military houses’ rule.

Surrender in World War II and the Beginning of American Occupation – September 2, 1945

World War II ended on September 2, 1945, after the act of full and unconditional surrender of Japan was signed aboard the American battleship “Missouri.” The American military occupation of Japan continued until 1951.

During this time, there was a complete reassessment of the values that had taken hold in the Japanese consciousness since the beginning of the century. Even such a once unshakable truth as the divine origin of the imperial lineage was subject to reconsideration.

On January 1, 1946, a decree was issued on behalf of Emperor Showa about the construction of a new Japan, containing a provision that became known as the “Hirohito and the Declaration of Humanity” This decree also formulated the concept of democratic transformation of Japan and the renunciation of the idea that “the Japanese people are superior to other peoples and destined to rule the world.” On November 3, 1946, a new Constitution of Japan was adopted, which came into force on May 3, 1947. According to Article 9, Japan henceforth renounced “war as the sovereign right of the nation” for all eternity and declared the rejection of maintaining armed forces.

The Beginning of Post-War Reconstruction of Japan – 1964

Post-war Japanese identity was built not on the idea of superiority, but on the idea of the uniqueness of the Japanese people. In the 1960s, a phenomenon known as nihonjinron — “discussions about the Japanese” — began to develop. Numerous articles written within this framework demonstrated the uniqueness of Japanese culture, the peculiarities of Japanese thinking, and admired the beauty of Japanese art.

The rise of national consciousness and reassessment of values were accompanied by world-scale events held in Japan.

In 1964, Japan hosted the Summer Olympics, the first to be held in Asia. The preparations for the games included the construction of urban infrastructure projects that became a source of pride for Japan.

High-speed “Shinkansen” trains were launched between Tokyo and Osaka, which are now famous worldwide. The Olympics became a symbol of the return of a changed Japan to the global community.