The samurai is one of the most iconic figures associated with the history of medieval Japan. One of the most intriguing and memorable eras in the history of the Empire of the Rising Sun is the time of feudalism and civil wars. But all that preceded was plunged into the shade. As the 19th century drew to a close, the question of how Japan developed into a feudal empire sparked widespread interest. Together, let’s explore the ancient Japanese past, from prehistory to the rise of the imperial shogunate.

At the Dawn of Japanese History: The Jōmon Period (14000 BC–300 BC)

The Shinto goddess Amaterasu was said to have provided the divine ancestry for the Japanese imperial family, giving them the right to rule the country. The Empire was just imperial in name at first, though.

While evidence of human habitation in Japan can be traced back to before 14,000 BC, the archipelago did not begin to take shape until around 300 BC. Peasants and fishermen made up the vast majority of Japan’s population at the time, and they lived in seasonal settlements that migrated across the country. The people who lived during the Jōmon period were known as “the market gardeners’ civilization” because they engaged in fishing, hunting, and primitive types of agriculture.

There was no such thing as money at the time, but jade daggers, ceramics, and shell-crafted things were beginning to emerge as popular handicrafts. Dogû is a kind of elaborate pottery that was discovered during the late Jōmon period, about 400 BC. There is no doubt that these works of art originated in Japan.

There was no Buddhism there at the time, just diverse shamanic rituals. It was believed that shamans could tap into the unseen realm and predict the future. They pray for prosperous harvests, appease the spirits, and protect against natural disasters and bad forces.

Japan and China: The Yayoi Period (300 BC–300 CE)

A dramatic shift in Japanese culture occurred at the start of the Yayoi period, about 300 BC. At this time, Shintoism was developing, governmental structures were being put in place, and trade with China was beginning to take place. The Yayoi, who came in from northern Kyûshu, the southernmost of the four main islands that make up the Japanese archipelago, were the ones who introduced these novelties.

Around 100 BC, Japan began producing its first metal goods, while the raw materials presumably originated in Korea. Communication with the Chinese and Koreans brought metalworking techniques, including bronze and iron, to Japan. Rapidly spreading from its origins in northern Kyushu, this groundbreaking idea has already changed the face of the whole island. Iron tools were put to use in farming, and the subsequent rise of the rice culture isolated and confined the rural population to their fields and homes made of mud and straw. Also, this system was only possible because of the rise of the settled population.

Landowners accumulated wealth, passed it down through the generations, and it increased the power of the ruling clan. Over time, they developed into something like feudal lords, complete with the power to impose taxes as well as administer justice and religious ceremonies. It was during this period that the first clans emerged. This aristocratic class’s religious function also bolstered their influence in politics. It was only they who had access to the holy items, could communicate with the other side, and understood the rituals of worship to the letter. The respect and admiration of others are a direct result of this accomplishment, further solidifying their position as leaders. Since bronze was less practical than iron for agricultural labor, it was relegated to the role of a symbol used in ceremonies, which eventually became an integral part of the governmental system.

In other words, the Yayoi era did not mark the end of the old shamanistic practices that had existed since the Jōmon period. Shinto, a religion with animist and polytheist elements, is still widely practiced in modern Japan. Shinto was founded on the idea that there were “6 million gods,” also known as kami (or spirits), who resided inside of everything and stood for each natural element. For instance, the fox deity Inari Ōkami, who was revered for his role in the harvest, was one of the most important kami.

In order to ensure a bountiful crop, they prayed to him. Shinto’s emphasis on cleanliness was similar to that of other religions. A person must periodically pray and do particular rites to rid themselves of their impurities (kegara), or else they will bring unhappiness and disaster upon themselves and everyone around them. The foundational myths of Japan, such as that the goddess Izanami and the god Izanagi created the country, have their origins in the Shinto faith.

The Japanese, who were known as the Wa at the time, first appeared in written Chinese. The fabled empress Himiko of Yamataitoku, who served as temporal ruler and high priestess, is said to have founded the empire around the third century (yet another fusion of spiritual and temporal powers). This empress may have existed, and she may have had some bearing on the later Yamato rule (from which the renowned battleship Yamato takes its name), although none of these claims have been verified.

The Emerging Empire: The Kofun Period (300 AD–538 AD)

Towards the end of the 3rd century, gradually emerges what would later become the imperial house: the Yamato court. The clans in the Bizen region, along the shores of the Inland Sea, gain power to the extent of establishing their dominance over the southern part of Honshu and a portion of northern Kyushu. The dominant clans include Soga, Katsuraki, Heguri, and Koze, later joined by the Kibi clans of Izumo (further northwest), Otomo, Mononobe, Nakatomi, and Inbe.

Each of these clans retains leadership in its region (kuni) but unites with others under the direction of the Yamato court. The Soga, Mononobe, and Otomo clans are particularly influential. Each claims imperial and/or divine lineage. The Katsuraki, initially the most powerful, had to yield to the Otomo, who endorsed Emperor Keitai during a succession dispute at the end of the 5th century.

The Yamato court developed its own administration, introducing positions such as the Minister of the Treasury. While the Emperor allowed clans relative autonomy on their lands, his authority was absolute, with even clan leaders submitting to his will. In practice, certain clans held more influence, often due to marital alliances with the Emperor’s family.

The aristocracy, comprising clan members under the leadership of their patriarch, was granted the first hereditary noble titles. Advanced military techniques, including cavalry, emerged, and sword usage also originated during this period.

The Yamato court became a key interlocutor with Korean kingdoms and the Middle Kingdom. By the late 5th century, the Emperor of Wa (Japan) began paying tribute to the Chinese Emperor, who, in return, recognized him as sovereign.

Chinese and Koreans migrated to the archipelago, forming entire clans like the Hata clan, consisting of Chinese descendants of the Qin dynasty, or the Takamuko clan. Korean princes were sent as hostages to the Japanese court in exchange for military support against the Manchu tribes.

This influx of population had unforeseen consequences, notably introducing Buddhism to the archipelago and disrupting Japanese traditions.

As the Yamato era concluded, Japan stood as a well-established empire, recognized by neighbors despite its distinct Shinto-based culture and political system. However, with the arrival of Buddhism and ensuing reforms, Japan entered its imperial period, commencing with the Asuka era.

The Yamato court, which had its beginnings in the fifth century, grew into the imperial court of Japan during the next six centuries, becoming more dominant both domestically and internationally. It all started with a series of changes in the sixth and seventh centuries that completely altered the country’s political structure. During this period of imperial rule, the arts, cultural and spiritual traditions, and even the written language advanced, despite the fact that war was uncommon. Without a doubt, the six centuries between the beginning of the Heian period and the end of the Muromachi period were the Golden Age of the Empire of the Rising Sun, which became known as Japan during this time (Nihon). However, the shift between the Emperor’s ascension to power and his consolidation of that authority was characterized by a wave of changes that were essential to the Empire’s survival.

Shōtoku Taishi’s Reforms (587–628)

At the beginning of the 6th century, the Yamato court was the scene of intense political intrigue. Little by little, the Soga clan, thanks to its marriage to the imperial family, succeeded in establishing itself, pushing aside the Katsuraki, Heguri, and Koze clans, and above all, to the detriment of the Mononobe and Nakatomi clans, who contested the establishment of Buddhism. But we’ll come back to this later.

By 587, the Soga clan was sufficiently powerful to allow its leader, Soga no Umako, to install his nephew on the throne and rule through this straw man (or rather child), with the help of prince regent Shotoku Taishi (574-622). Later, the emperor, showing too much inclination towards independence, was assassinated and replaced by Empress Suiko (593-628). Shotoku Taishi was the first to introduce reform.

A devout Buddhist and a great connoisseur of Chinese literature, he drew inspiration from the Confucian principles governing government in the Middle Kingdom and applied them to Japanese reality. Shotoku Taishi introduced the concept of the Mandate of Heaven, according to which the Emperor holds his power by divine right and reigns according to the will of heaven. He also drew up a seventeen-article constitution, emphasizing the value of harmony and the Buddha’s teachings, the absolute priority of imperial orders over all other considerations, and praising the Confucian virtues of devotion and obedience.

This “constitution”—a debatable term, given that it does not really lay down the institutional foundations of the state but rather its guiding principles in moral and spiritual terms—is accompanied by a revolution in the system of ranks and etiquette, which, however laughable it may seem from the outside, is of major importance in a highly ritualized political system.

To complete the “Sinicization” of Japan, Buddhist temples were built, the Chinese calendar was adopted, and a new administrative unit inspired by the Chinese model came into force, the Gokishichido (5 cities, 7 roads). Students and diplomatic missions were sent to China, then under the rule of the Tang dynasty. However, although relations were more regular and intense, particularly on a cultural level, than during the Kofûn period, it was also at this time that rivalries between China and Japan developed. Indeed, messages from the Emperor of the Rising Sun to the Emperor of the Middle are now addressed as equals, as Japan no longer considers itself a vassal of its Chinese neighbor.

By the time Shotoku Taishi and Soga no Umako died, leaving the Soga clan to pull the strings of an Empire, Chinese culture had permeated Japanese customs and politics. Regarded with suspicion by the people, particularly Buddhist rites, these traditions from elsewhere were nevertheless to become an important part of the unique culture developed by Japan over the centuries that followed.

The Taika Reforms

The Soga clan, despite its period of success, did not survive long after the death of Shotoku Taishi. In the year 645, palace intrigues led to a coup d’état aimed at ending Soga’s grip on power. The Isshi Incident, also known as the Naka no Oe Uprising and Nakatomi no Kamatari (the clan that would later become the Fujiwara clan), signaled the start of the Taika Reforms, which means “Great Change.”

As control was no longer inherited, the central government initially confiscated land. Each generation, the lands were handed over to the imperial administration, responsible for their redistribution. Naturally, this meant that a family losing imperial favor could be reduced to nothing at a moment’s notice. Similarly, the hereditary titles of clan leaders were also deprived of hereditary transmission.

Subsequently, taxes on crops, silk, fabrics, and cotton were imposed to finance the expansion of the administration. A labor duty was instituted for the creation of a militia and the construction of public buildings. Finally, the division into Gokishichido was abolished, and the country was divided into provinces, led by governors accountable only to the imperial administration. Districts and townships were established to exert even more control over the country’s administration.

Additionally, the Emperor and his supporters, particularly the Kamatari, focused on establishing the ritsuryo, a set of penal and administrative rules. The ritsuryo was written in several stages: the Ômi code, the first version, was completed in 668; the Asuka Kiyomihara code in 689; and the latest version, the Taihô code, completed in 701, remained in effect with minor modifications until 1868. The penal code resembled a Confucian code, favoring lighter punishments over severe penalties.

The administrative code established the Jingi-kan, a body dedicated to court rituals and Shinto traditions, and the Daijo-kan, which created eight ministries for central administration, ceremonies, the imperial household, civil affairs, justice, the military, public affairs, and the treasury. This highly effective tool strengthened the imperial house’s ability to govern the country, contributing to the stabilization of its power.

The Introduction of Buddhism in Japan

The introduction of Buddhism to Japan likely occurred through immigration from the Korean Peninsula. In the 6th century, close relations between the Yamato court and Korean kingdoms developed, particularly after Japan’s intervention to support the Baekje kingdom against Mongol invaders. In 538, the first delegation was sent to Japan to spread the Buddhist faith. Initially embraced by the Soga clan and subsequently transmitted to the aristocracy, Buddhism faced resistance from the common people, supported by the Nakatomi and Mononobe clans.

As Buddhist traditions gained ground, Shinto traditions declined. Imperial decree forbade the burials known as “kofun,” or keyhole-shaped tumuli. The consumption of meat, including horses, birds, and dogs, was also forbidden.

Moreover, Buddhism was not the sole philosophy to make its way to the archipelago. In the mid-7th century, the first Japanese Taoist monastery was built on Mount Tonomine. Some imperial burials adopted the octagonal shape, symbolizing universal order in Taoism and indicating the strength of its influence.

As the Asuka period concluded, the empire was firmly established, with clans and the populace devoted; political stability prevailed; and the archipelago remained unscarred by conflicts. Such prosperity led the Japanese Empire to view itself as equal to the Middle Kingdom. A real cultural flowering was about to take place in what is now known as the Empire of the Rising Sun.

The Nara era commenced with the establishment, in the year 710 CE, of Japan’s first permanent capital in the city of Nara, located in the central part of the country. The Asuka era reforms gave rise to an imperial bureaucracy, which also settled in Nara. Rapidly, the city became Japan’s primary urban center, hosting a population of 200,000 people.

This urbanization, bringing together thinkers and artists from across the country, facilitated a genuine cultural explosion. During this period, imported Chinese culture associated with Buddhism waned, despite the capital being planned similarly to the Chinese Tang Dynasty capital, and was replaced by an original Japanese culture. Concurrently, the permanence of the imperial court heightened palace intrigues and power struggles. While the Nara and Heian eras are synonymous with cultural blossoming in Japan, they are also inseparable from the decline of imperial power and the onset of the first clan wars.

Development of Japanese Arts and Culture

The first sign of cultural renewal is the abandonment, starting in 710, of the titles and court attire of the Chinese tradition. Beauty standards evolve, and both aristocratic men and women powder their faces to whiten their skin and blacken their teeth. Men adopt the practice of wearing a thin mustache, while women paint their lips scarlet, all in an effort to approach the divine “perfection” described in Shinto pantheon legends. The first complex court robes also make their appearance, known as “junihitoe,” consisting of multiple layers of fabrics arranged according to a complex code based on the season and sacred festivals.

Artistically, the major development of these two eras was undoubtedly literary. Although Chinese remained the court language, the emergence of “kanas”—characters designed to express nuances, typically Japanese—led to an explosion of literature. The first major works emerged at the beginning of the Nara era, with the Kojiki (712) and the Nihon Shoki (724), the first imperial chronicles. Later, fictional works such as the famous Tale of Genji, the first Japanese novel, and The Pillow Book by Sei Shonagon, one of the earliest female authors, were written. Poetry also experienced impressive growth. Japanese poems, known as waka, flourished during this time, as being a poet was a mark of an enlightened and serene spirit. Fujiwara no Teika, Murasaki Shikibu, and Saigyo are among the famous poets.

To fully grasp the significance of literary creations during this period, the current national anthem of Japan, “Kimi Ga Yo,” was written during the early Heian era, around 800.

Buddhism in the Empire of the Rising Sun

During the Nara period in Japan, as Chinese traditions fell into disuse and the Tang dynasty’s court was considered decadent, Buddhism, imported from China, did not follow the same decline. Well-established in the archipelago, the Buddhist clergy engaged in a rapid process of adaptation to Japanese reality. Despite being closely connected to the emperors and empresses of Nara, this adaptation did not occur without posing some challenges.

At the beginning of the Nara era, Buddhism gained significant prominence. A vast monastic complex, the Todaiji temple, was constructed with a colossal bronze statue of Buddha at its center, known as Daibutsu, towering over 16 meters in height. Assimilated to the representation of the Sun Goddess, Amaterasu, this statue synthesized Buddhism from the continent with the older traditions of Shinto, native to Japan. Still visible in Nara, it remains a highly esteemed monument for both Japanese and foreign tourists. Provincial temples, called kokubunji, were established to extend the influence of Buddhism to rural regions where Shinto still held strong roots.

The archipelago’s oldest monasteries also date back to this period, such as the grand monastery on Mount Hiei, built by the Tendai Buddhist sect, closely associated with the emperor and basing its doctrine on the Lotus Sutra. Cultural achievements and artistic works from the Buddhist world found their way to Japan, notably the Shoso-in temple, which archived sacred texts from as far back as the early caravanserais of Central Asia on the Silk Road. The development of religious art played a crucial role in Buddhism’s influence in Japan, encompassing silk paintings, Buddhist statues, temple decorations (mandalas), sculpture, and calligraphy.

Buddhism: State Religion? No, but…

During the Heian period in Japan, Buddhism ceased to be the state religion but remained a means for the imperial family to uphold and expand its power and influence. Empress Kôken (749–758) invited a large number of Buddhist priests to the court during her reign. Even after her abdication in 758, she maintained strong ties with the clergy, particularly with a priest named Dokyô. When her cousin Nakamaro of Fujiwara rebelled against her, she successfully defeated him, subsequently dethroning the reigning emperor and ascending to the throne as Empress Shotoku (764–770). These actions shocked the court and led to the exclusion of women from the succession line. The clergy’s involvement is evident, as the empress, in gratitude for her victory, had nearly a million wooden charms manufactured.

In the later Heian era, the Tendai and Kukai Buddhist sects garnered support from numerous aristocrats, including Emperor Kammu, a staunch admirer of Tendai. Both sects aimed to connect the clergy and the state, believing that their religious conduct required influencing political decisions. During this period, the clergy’s land holdings grew in importance. Enjoying tax exemptions due to their religious status, monasteries also caused significant financial losses, threatening the imperial administration’s financial stability.

While there was a cultural explosion during the Nara period and the early Heian era, which was characterized by the development of modern Japanese writing and the influence of Buddhism, cracks started to appear during what appeared to be the heyday of imperial power. These fissures persisted throughout the Heian era, ultimately leading to the fall of the Empire and the rise of the shogunate.

The transition from the Nara era to the Heian era, though seemingly inconspicuous, carried significant implications. In 794, the capital was once again moved, this time from Nara to Kyoto (then known as Heian-kyô). Built on a larger scale but following the same plan as Nara, Kyoto stood as a monumental symbol of the imperial era’s flourishing.

Emperor Kammu chose Kyoto to strengthen the seat of imperial power, considering its better access to the sea, a river route, and, most importantly, its proximity to the eastern provinces. By establishing the government’s seat there, Kammu aimed to make it a strong power center that would extend imperial dominance across the archipelago. Military victories in the northeastern part of Honshu marked an initial step toward success, but the seeds of the decline of imperial authority were already present.

The Fujiwara Regency

Emperor Kammu, who seemed to be leading the Empire towards power, died in 806, leaving behind a powerful throne but a disputed succession. At exactly the same time, the great noble families began to regain their lost power from the reforms of the sixth century. Farmers and independent peasants who owned their own land since these reforms found it more advantageous to sell their property titles to these families. They would then work on these lands as sharecroppers in exchange for a fraction of the harvest. The result of this trend was that the extent of land controlled by the nobles was rapidly expanding. These lands formed “shōen,” large parcels, overseen by a manor or a castle.

This was somewhat reminiscent of the existing feudal system in Europe, except that the peasants were not serfs tied to their land. Furthermore, while peasants could not escape the controls on their heritage and tax collection, the great noble families were politically powerful enough to obtain substantial reductions in their taxes. A similar situation existed for monastic institutions. Monasteries also began to form shōen, becoming a significant factor in the country’s economy.

Gradually, emperors lost the absolute control they had over the administration as the Empire’s financial resources dwindled. The Fujiwara family, one of the most powerful noble families in Japan, which owned immense cultivable areas in the north of the country, gradually approached the seat of power, particularly through marriages with the imperial family. During the ninth century, the Fujiwara took the lead in the Imperial Cabinet, and several of them assumed the role of regent. The management of the Empire’s affairs gradually fell under the control of their family administration, which also managed their land holdings. The Fujiwara family surpassed imperial officials at all levels.

While other clans did not have an administrative machine as extensive as the Fujiwara, they nevertheless developed their own administration. The foundations of the feudal system were already in place.

The Rise of the Military Class

As the finances of the Empire collapsed, maintaining a substantial imperial army became increasingly problematic. Gradually, the management of military affairs became as much, if not more, the responsibility of noble families than the imperial administration. The shōen, in fact, were both the reason and the means to develop armed forces: they enabled the payment and sustenance of troops, who, among other duties, defended against raiders and the incursions of the Emishi (tribes in northern Japan). Private militias, whether under the command of noble families or religious orders, marked the emergence of a new social class—the warriors (bushi), later known as samurai (those who serve).

The larger families, controlling more extensive lands, also possessed the most numerous armies and consequently received military titles and corresponding prestige from the imperial court. Clans such as Taira, Fujiwara, and Minamoto, in particular, took center stage in the military arena. A tense situation developed, with each clan wary of the others, yet none taking the initiative for open conflict. Eventually, the balance was disrupted by Emperor Go-Sanjô (1068–1073).

Unlike several of his predecessors, Emperor Go-Sanjô managed to diminish the power of the Fujiwara. He established an official land registry, and as a significant portion of Fujiwara lands had not been properly recorded with authorities after being acquired from small landowners, the Fujiwara clan lost a substantial portion of its lands and income.

The Hôgen Rebellion (1156), supported by the Taira and Minamoto, further dispossessed the Fujiwara of their dominant position, compelling them to retreat to their northern strongholds. While they retained their official positions, the Emperor regained control of the administration, establishing an imperial council composed of abdicated emperors. Internal divisions within the clan accelerated its decline. For the first time, a war had brought an end to the power of a major clan.

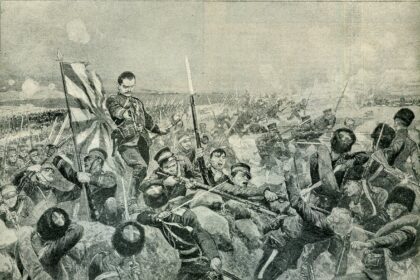

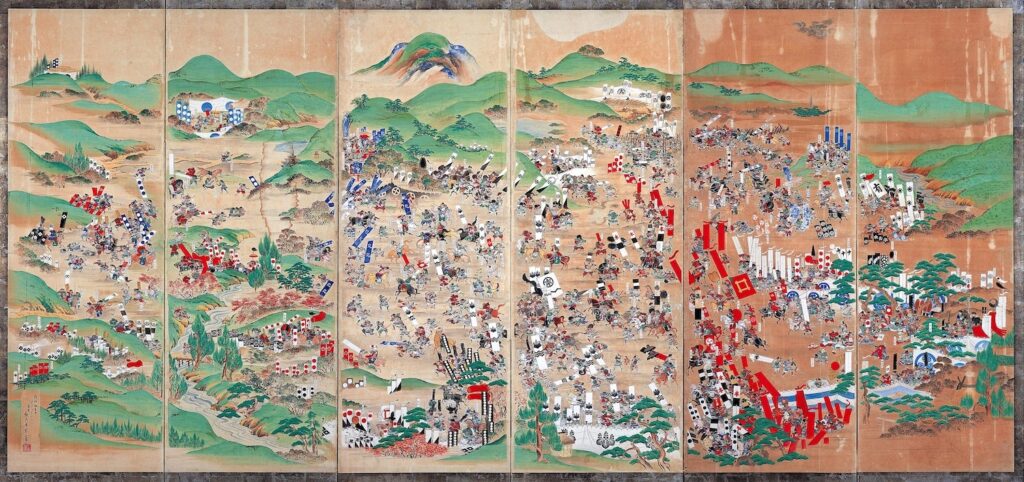

The Genpei War, 1180–1185

The Gempei War was Japan’s first true civil war, and it occurred shortly after the collapse of the Fujiwara, a family that had been pushed to the political outside. From 1180 on, this one battled against the Minamoto and Taira dynasties. There were indicators of an impending big battle going back many decades. The Minamoto initially rebelled against Taira rule of the imperial court in 1160, during the Heiji rebellion, but were soon put down.

The Taira clan, led by the legendary Taira no Kiyomori, controlled imperial politics during the period. He had the nerve to become clan chief and then seize control of modern-day Kobe, the hub of the busiest commerce route between Song China and Kyoto, the imperial capital. Because of this, he was able to provide a comfortable lifestyle for his loved ones while still advancing his career and gaining influence. Kiyomori created and unmade monarchs (Nijo, Rokujo, Takaku) as he pleased in his role as Daijo Daijin (Chief Minister of the government, second in power only to the Emperor) and administrator of the Empire.

By doing so, the Taira earned the enmity of many in the court who were envious of their authority. Assisted by the Minamoto family, Prince Mochihito, brother of the deposed Emperor Gosanjo, started the war in an effort to end the Taira dynasty’s rule. When Mochihito issued a summons to arms, the latter responded by relocating the capital to Fukuhara (current-day Kobe), which was inside the center of their fief.

In the summer of 1180, troops from both families converged, and in the first fight, at Uji, the Minamoto were utterly defeated. Despite the assistance of the warrior-monks of the Mount Hiei monasteries, Prince Mochihito and the Minamoto clan chief, Minamoto no Yorimosa, were both slaughtered. The Taira forces besieged and ultimately destroyed most of these monasteries. The Minamoto were beaten for the second time on September 14, 1180, in Ishibashiyama, and so they withdrew to their seaside stronghold of Kamakura. Taira no Kiyomori passed away in February of the following year, putting his youngest son in line to become shogun. With both forces separated by hundreds of kilometers and experiencing supply issues due to weak crops, fighting froze in the spring of 1181.

After two years of doing nothing, the army resumed its advance in the spring of 1183. Although the Minamoto were unprepared and their warriors were untrained, the Taira were nonetheless totally destroyed by them at Kurikara. With time, the Taira were unable to escape Kyoto and were forced to retreat to their homelands in western Honshu and Shikoku. Infighting between Yoshinaka and Yoshitsune, two members of the Minamoto family, over who would rule the clan meant that the Taira never fully recovered from the catastrophes of 1183.

After besieging Ichi no Tani and Dan no ura, they were eventually defeated in the naval battle of Shimonoseki in the Inland Sea. After the Taira family was annihilated, the Kamakura Shogunate took power. The chief of the Minamoto clan became Japan’s military dictator, known as the Shogun. As a result of this conflict, the emperors were demoted to the role of symbolic figures, while the shogun assumed practical control for the next 500 years. The samurai emerged as Japan’s new elite class when the country entered its feudal period.

In 1185, the Minamoto clan triumphed over the Taira clan and became the dominant family in the Japanese archipelago. The Taira family’s former dominance and influence over the government were history. However, the war proved the superiority of military might over imperial control. For a long time, samurai were seen as little more than powerless slaves, but over time, they started to establish a warrior caste and assume more responsibilities. Shortly after the Minamoto triumph, the imperial court reinforced this status quo by bestowing upon Minamoto no Yoritomo the title of Seii Tai Shogun, therefore vesting absolute authority in him.

Emergence of the Samurai: The Kamakura Period (1185–1333)

The Kamakura era began in 1185, when Minamoto no Yoritomo, the first shogun in centuries, established the seat of his so-called bakufu government (tent government, in reference to the fact that military chiefs held power there) in Kamakura, some 50 kilometers from present-day Tokyo. As with any new regime, Yoritomo’s first priority was to consolidate his power. He created three ministries essential to the governance of the state. The first dealt with finance and administration. The second dispensed justice in times of peace and organized the raising of troops from the shogun’s vassals in times of war. The latter ensured that the shogun’s decisions were implemented.

The Kamakura shogunate’s other source of power came from the lands under its control. After the defeat of the Taira, much of the land in central and western Japan came under Minamoto’s control via confiscation. The Minamotos then distributed these lands among those who would become their vassals, thereby securing their loyalty. This was the birth of the feudal system and of the samurai caste, made up of landowners and their vassals who had sworn loyalty and fought for their lord.

As he established this new system, Yoritomo found himself fighting against those who resisted these changes. The Fujiwara clan, which owned most of the land in northern Japan, was deeply rooted in traditional values. They saw the Minamotos as upstarts who endangered imperial power itself. Moreover, the Fujiwara refused to be accountable to those they saw as rivals. Eventually, the situation degenerated into a new civil war, much faster than the previous one, which ended in 1189 with the defeat of Fujiwara no Yasuhira and the end of Fujiwara’s power, which never recovered.

When Yoritomo died ten years later, in 1199, Japan’s political landscape was unrecognizable. While the old imperial court remained in Kyoto, the new Minamoto vassal landowning families had regrouped at the Kamakura court. For the first time, there were two true centers of power in Japan. But, Yoritomo’s death was also the beginning of the end for the Minamotos.

The internal dissension that had already manifested itself during the war against the Taira resumed with a vengeance. His son Yoriie succeeded him as head of the clan but proved unable to maintain Minamoto’s hold on the shogunate. In the early years of the 13th century, a warrior clan, the Hôjô, seized the post of Regent (Shikken) and created the posts of Tokuso and Renshô, titles that were normally honorary but which they used to strip the Minamoto shogun of his prerogatives. The Hôjo were, de facto, the new masters of shogunal power.

Although the position of the shogun had been created in honor of those who defended imperial power, the shogun had gradually come to encroach on the emperor’s power. In 1221, Emperor Gô-Toba declared the second Hojo regent, Yoshitoki, an outlaw and went to war against the shogunate. The Hojo clan and its allies crushed the imperial forces in less than a month, exiling Gô-Toba and his sons. This revolt, known as the Jokyû Incident, marked the end of imperial power, with the emperor reduced to a symbolic role.

The Hojo kings established the Council of State in 1225, a new political structure where the other lords shared legislative and judicial authority. This sharing of power in no way diminished the importance of the shogun and regent and enabled them to give other clans the opportunity to exercise a share of power, reducing the risk of a coup d’état. In 1232, a new legal code was established. Unlike the rules in force until then, which were based entirely on the theories of Confucius, this code, the Goseibai Shikimoku, focused on the creation of laws and precise punishments according to crimes and was devoid of any philosophical scope while being much clearer and more practical to use.

The Hojo regents maintained absolute authority for around fifty years. Until the first Mongol invasion of Japan in 1274… In 1268, the Mongols, under Kublai Khan, created the Yuan dynasty and began ruling China. The latter desired to include Japan among his vassal states and hence issued an ultimatum demanding that Japan surrender and pay tribute. The Hojo regents promptly rejected the ultimatum. In 1274, about 23,000 Mongols, Chinese, and Koreans arrived on the northern part of Kyushu in a fleet of 600 ships, armed with grenades that had never been seen in Japan before.

The samurai quickly lost ground, unaccustomed to the group formations employed by the Mongol officers. However, a typhoon ravaged the Mongol fleet less than a day after landing. In 1281, Kublai Khan launched a second invasion, but the fleet was once again wiped out by a typhoon after an apparently successful landing and a few weeks of fighting in Kyushu. Japanese Shinto priests called these typhoons the kamikaze, the divine winds that come to defend Japan against foreign invaders.

However, typhoons were probably not the only cause of Kublai’s defeat. The remains of ships found at the site show many defects. It is thought that Chinese and Korean shipbuilders, hoping to shake off the Mongol yoke, built vessels adapted to river navigation, not to the high seas, let alone storms. As a result, many ships sank where ships with more suitable hulls would have resisted.

The invasions had not left the archipelago unscathed. The financial cost of raising troops and preparing for defense had led to new taxes, and the Hojo regency was becoming less and less popular. To make matters worse, bands of ronin, masterless samurai who resorted to brigandage to survive, began wreaking havoc across the country. To avoid the worst, the Hojo further weakened imperial power by creating a second court. The Northern and Southern Courts, from two different branches of the imperial family, were supposed to rule alternately, thus further reducing the emperor’s remaining influence.

While this solution worked for a few decades, in 1331, Emperor Go-Daigo of the Southern Court ascended the throne, intent on ridding himself of the Hojo regents and the shogunate. The Hojo clashed with forces loyal to the emperor but were defeated by the treachery of the Ashikaga family, led by Takauji, which led to the dispersion and subsequent rout of the shogunate forces. In 1333, Emperor Go-Daigo re-established imperial power for a brief period known as the Kemmu Restoration.

The Kenmu Restoration (1333–1336)

Go-Daigo’s main goal—to retake control from the shogunate and effectively rule Kamakura without interference from the military—is now possible thanks to the success of his uprising. However, the Kemmu Restoration was short-lived, primarily due to a strategic error on the emperor’s part. He believed he had the support of a significant portion of the samurai class and the so-called “loyalist” military clans and families. In reality, these loyalist samurai and clans had not engaged in the revolt to support the emperor but rather to end the Hojo domination. Consequently, after the emperor’s restoration as the true leader, Go-Daigo neglected to reward his allies, assuming their allegiance. By failing to compensate the samurai, he lost their support, leading to new disturbances in the country.

Simultaneously, the majority of the warrior class is discontented with what they perceive as ingratitude, and the major military families are concerned about the emperor’s initiatives to establish a civilian-dominated power. Violent political clashes ensue, particularly between Prince Morinaga, the emperor’s descendant, and Takauji, the leader of the Ashikaga clan, each vying to place their followers in strategic positions. Gradually, Takauji manages to distinguish himself as the leader and representative of the samurai. Eventually, he imprisoned Morinaga on charges of treason in Kamakura in 1335.

In that year, an unexpected event provided Takauji with the opportunity he needed. A survivor of the Hojo regency, Tokiyuki, revolted and temporarily regained control of Kamakura. Before leaving, the Ashikaga-appointed governor ordered Morinaga’s execution, shifting the blame onto the Hojo. Takauji then asked the emperor to grant him the title of shogun to quell the rebellion. Despite Go-Daigo’s disagreement, Takauji left Kyoto for Kamakura and ended the Hojo revolt. When the emperor ordered him to return, he refused, signaling that Takauji and the Ashikaga were rejecting the emperor’s authority, leading to the secession of the Kamakura region.

Swiftly, an imperial army assembled to defeat the Ashikaga, while a second army marched towards Kamakura to aid its defense. On November 17, 1335, Takauji’s brother sent messages throughout the country, calling on all samurai to defend the Ashikaga against the emperor’s tyranny. Simultaneously, the imperial court urged the samurai to help defeat the Ashikaga rebels.

When the actual war began, most samurai were convinced that Takauji Ashikaga was the leader they needed to assert their interests. With a significant numerical advantage, Ashikaga forces defeated the imperial armies, and on February 25, 1336, Takauji entered Kyoto, putting an end to the Kemmu Restoration.

The Muromachi Period (1337–1573)

After more than a year of debates and dissensions, Takauji Ashikaga was finally appointed Shogun in 1337. The Ashikaga shoguns maintained their reign for nearly 250 years, until 1573. This period was named Muromachi, after the district where the shoguns’ palace was located. It was relocated back to Kyoto in 1378 by the third Ashikaga shogun. This geographical proximity aimed to exert much tighter control over the imperial court. While the Kamakura shogunate had never truly eradicated imperial power, the Ashikaga went so far as to destroy the notion that the Emperor should reign directly, making the position of Shogun indispensable for the Empire’s proper functioning.

Under the Kamakura shoguns, the governor’s position was merely that of an agent acting on behalf of the shogun. However, at the beginning of the Muromachi era, it became synonymous with extended powers, gaining almost complete control over the lands they ruled, answering only to the shogun. These lords, called daimyos, quickly became the most powerful political figures in the Empire directly after the shogunal court.

In 1392, the Ashikaga also reunified the separated Imperial Court under the Hojo regency, another measure to control imperial power more easily. Eventually, it was the rise of the shoguns that led to the decline of the Ashikaga, to the point where the daimyos could directly support certain candidates for imperial succession, facilitating the ascent to the throne of emperors favoring their interests, generally to the detriment of the Shogun. From the fourth Ashikaga shogun onward, the influence of the shoguns slowly declined, along with their prestige.

Officially, the Ashikaga remained in power until 1573, but long before their fall, signs of their decay became increasingly visible. The Ônin War, between 1467 and 1477, triggered by a dispute over imperial succession, marked the beginning of a previously unknown period of turmoil in Japan. A period of civil war where every family and every clan defended only their own interests plunged the country into chaos.

This troubled period is known as Sengoku-jidai, the age of warring states.

1477: Japan is in complete chaos. The Ônin War has just ended, but the troubles do not subside. The Ashikaga dynasty, which has been ruling the country on behalf of the Emperor with the title of Seishi Taishogun since 1337, is losing its grip and proves incapable of ending conflicts that emerge everywhere in the country among the dozens of noble families and clans. Japan gradually lost its cohesion, sinking into one of the most turbulent periods in its history, the Sengoku-jidai (a time of unprecedented upheaval and transformations), the era of warring states.

Nanban and Gunpowder

In 1543, a typhoon off the coast of Tanegashima, in southern Japan, kidnapped a ship full of Portuguese sailors and brought them to the Japanese islands. There was a profound shock since the Japanese had never before had any meaningful interaction with European cultures. The Portuguese were referred to as “Nanban” by the Japanese. This term translates to “Southern Barbarians.”

Despite an embargo placed by the Emperor of China in retribution for Japanese piracy, the Portuguese started importing Chinese commodities, notably silk, into Japan within a few years. Eventually, business picked up speed. The port of Nagasaki opened as a commercial station in 1571, and commerce with the Portuguese increased rapidly. Shortly later, in 1578, the daimyo of the Sumitada clan requested Portuguese aid in fending off an assault on the daimyo, and in return, the port was permanently surrendered to the Jesuits.

To Japan next came the Dutch in the year 1600. The competition with the Portuguese for control of commerce with the Land of the Rising Sun was severe.

There were two key shifts that the introduction of Westerners to Japan brought about. One of the causes was technical. Gunpowder’s use in Japanese military operations was nascent in 1543. The intention behind this seemingly minor innovation was to dramatically shift the power dynamic. Suddenly, families armed with Portuguese arquebuses could compete with their more formidable neighbors.

The availability of such weapons also contributed to the escalation of hostilities. Fighting broke out on the southern island of Kyushu when the Portuguese arrived, and it wasn’t until later that harquebuses became commonplace across the archipelago. They were dubbed Tanegashima after the island where the Nanban had their first encounter. By 1560, harquebuses were widely used in warfare.

The harquebuses were not the only thing the Westerners brought with them, though; the Christian faith was also a major contributor to tensions. Six years after the first meeting, Nagazaki built its first church. The founder of the Jesuits, the Catholic Church’s missionary arm, set his sights on Japan in an effort to win over the local population. In under 30 years, the majority of the daimyo in Kyushu and more than 130,000 other Japanese were converted.

Christianity flourished across Japan, from the lowest of the low to the highest of the high, despite the social boundaries that existed between the various classes. While some daimyo were willing to accept Buddhism without investigation, others were suspicious of the new faith, believing it was being utilized by the Nanban to penetrate Japan. Christian and non-Christian daimyos began fighting with one another.

Gekokujo: The Powerful Are Defeated by the Humble

The clan wars tearing apart the country witnessed unprecedented events. The ancient, powerful, and respected clans, along with their leaders, who, according to the Japanese social system, are masters of their vassals, are gradually losing ground to dynamic new clans and ambitious leaders. The established order is shattered by internal rivalries, and those who, in times of peace, would have submitted to the will of dominant families now struggle to take the lead. This phenomenon is known as Gekokujo, roughly translated as “the humble overcome the powerful.”

As a result, the war rapidly degenerates, occurring not only between clans but also within clans. Various families and branches within the clan vie for control. In the Echigo region, north of Kyoto, on the coast of the Sea of Japan, peasants and commoners rise up following the Ikko-ikki religious movement (a Buddhist school of the “Pure Land”) and assert their independence. They receive support from the minor nobility and rōnins, the samurai left masterless by the war.

In the province of Iga (Skull Valley), villagers free themselves from the grip of feudal lords, establishing a league (ikki) comprised of peasants, rōnins, and the clergy to defend against external aggressors. The region is notably renowned for its ninja clans.

In summary, this phenomenon, accelerating the decomposition of the country into rival factions, also presents a unique opportunity to end the social stagnation that led to the decline of the Ashikaga dynasty.

The Unification of Japan: Oda Nobunaga (1534–1582)

During this turbulent period, three ambitious and skilled men emerged to reunify Japan under a single banner. The first among them took the lead of the Oda clan in 1551, a minor clan in the Owari province in central Japan. His name was Oda Nobunaga.

At that time, the Oda clan was in a precarious situation, being a vassal of Shiba Yoshimune, the governor of the province, and divided into several factions. With the support of Yoshimune and one of his younger brothers, Oda Nobumitsu, Nobunaga managed to overcome the opposition of Nobutomo, another brother who assassinated Yoshimune to deprive Nobunaga of support. Nobunaga eventually got rid of his brother and rival in Kiyosu, then used Yoshimune’s son as a puppet to form an alliance with a powerful neighboring clan, the Imagawa. After eight years of conflict and the elimination of another brother, Oda Nobunaga finally succeeded in unifying the Owari province under his leadership in 1559.

The following year, he had to defend against an incursion by the Imagawa, who marched with 25,000 men towards Kyoto, while Nobunaga could only muster 3,000. Against all expectations and the advice of his counselors, Nobunaga attacked the Imagawa forces, using straw dummies and the cover of a providential storm to sow chaos among his enemies. This was the Battle of Okehazama, during which the Imagawa general was killed. The Imagawa quickly lost their position, and Nobunaga took the opportunity to ally with one of their former vassals, the Mitsudaira, in 1561.

Between 1561 and 1567, he focused on seizing the neighboring Mino province, diverting the vassals of the Saito clan from their master before launching a lightning campaign that swept away the Saito in a few months. After this victory, he changed his personal seal to “Tenka Fubu,” meaning: Unify the nation with military might.

In 1568, at the request of a member of the Ashikaga family, Nobunaga set out to conquer Kyoto, quickly driving the Miyoshi clan out of the city and making Ashikaga Yoshiaki the 15th Ashikaga shogun. Almost immediately, Nobunaga began to restrict the shogun’s powers, thereby increasing his own power and making it clear to the daimyo that he intended to use the shogun as a puppet.

This bold move was too much for Nobunaga’s rivals. Led by the Asakura, former masters of the Oda, the Asai, and the Ikko-ikki launched a concerted aggression against the Oda clan, inflicting heavy losses. Eventually, with the help of their allies, the Tokugawa (formerly Mitsudaira), the Oda counterattacked, breaking the Asai and Asakura armies at the Battle of Anegawa. Subsequently, Nobunaga, known at the time for his Christian sympathies, dealt with the Buddhist uprising against him. He burned the Enryaku-ji temple in 1571 and besieged the Nagashima fortress. Eventually, the struggle against the Ikkō-ikki Buddhists cost him several thousand soldiers and two brothers, and he finally set fire to the castle in 1574, ending the resistance.

Meanwhile, as Nobunaga was entangled on his western flank, the Takeda clan seized the opportunity to attack from the east, starting by invading Tokugawa lands, defeated at the Battle of Mikatagahara in 1573. The Tokugawa managed to slow down the Takeda by organizing night raids, and after the death of Takeda Shingen, the Takeda retreated. At the same time, the Oda completed the conquest of the Asai and Asakura clans.

In 1574, Nobunaga turned to the east and, with the Tokugawa, invaded the Takeda clan’s lands, reducing the entire Takeda forces to nothingness at the Battle of Nagashino, thanks in part to the innovative use of arquebusiers arranged in a triple line of fire for continuous shooting. The Takeda never recovered from this defeat.

For three years, Nobunaga consolidated his positions, but the Mori to the west broke the naval blockade of the surviving Buddhist castle at Igashiyama. In 1577, the future Toyotomi Hideyoshi, Nobunaga’s lieutenant, was sent to attack the Mori clan. The Uesugi clan, under the leadership of Uesugi Kenshin, gathered northern clans to attack the Oda that same year, resulting in a crushing defeat at Tedorigawa. Only Kenshin’s death ended the second anti-Oda coalition.

In 1582, Nobunaga controlled half of Japan, including Kyoto. The conquest of the Mori continued, and the northern clans could no longer offer credible resistance. Nobunaga fell victim to a coup that Mitsuhide, one of his lieutenants, orchestrated while he was traveling to the western front. Mitsuhide’s troops surrounded the Honno-ji temple where he was staying, killing Nobunaga and his eldest son, casting doubt on the succession.

Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1536/37–1598)

After the death of Nobunaga, the situation was chaotic. Hashiba Hideyoshi emerged to quell the rekindled chaos. This former lieutenant of Nobunaga, the son of the ashigaru (peasant class), initially served Nobunaga as a sandal-bearer, a very low-ranking servant.

At the Battle of Okehazama, Nobunaga noticed him and became interested in his sharp-witted servant. In 1564, Hideyoshi was sent to rally deserters from the Saito clan to the Oda cause. In 1567, the Battle of Inabayama was won thanks to Hideyoshi’s idea to flood the valley where the castle was built. In 1573, Nobunaga made him the daimyo of a fief in North Omi, and Hideyoshi continued to faithfully serve Nobunaga, leading a war against the Mori clan between 1577 and 1582.

Upon learning of Nobunaga’s death due to Mitsuhide’s betrayal, Hideyoshi immediately negotiated a peace treaty with the Mori and turned his forces against the traitors at the Battle of Yamazaki. After avenging his master, it was time to organize Nobunaga’s succession at the Kiyosu meeting. With his eldest son dead, several candidates vied for succession: Oda Nobutaka, Oda Nobukatsu, and Oda Hidenobu. Hideyoshi chose to support the latter, with the help of two of the three Oda clan advisors. Through two swift victories, he eliminated Shibata Katsuie, Nobutaka’s advocate, and established a status quo with the Tokugawa defending Nobukatsu.

Once his candidate was installed as the head of the Oda clan, Hideyoshi began strengthening his grip, starting the construction of his own fortress, Osaka Castle, in 1583. During this relatively calm period, he was officially adopted by the regent family of Fujiwara, receiving the title of Kampaku (“regent”) and the name Toyotomi.

Taking advantage of his dominant position, Hideyoshi launched a conquest of the South, gaining control of Southern Honshu and overthrowing the Chosokabe clan’s dominance on Shikoku. In 1587, he landed in Kyushu and, strongly opposing the spread of Christianity, banned missionaries from the island. To prevent the formation of new leagues (or ikki), he prohibited peasants and commoners from carrying weapons, initiating what was later called the sword hunt. Once his control was established in the South, Hideyoshi turned his attention to the East again, defeating the Hojo clan, the last major independent clan, at the Battle of Odawara. He then offered their Kanto lands to Tokugawa Ieyasu if the latter submitted, which he did. Hideyoshi became the master of a unified Japan.

Unfortunately, his ambitions did not stop there. Now that the country was under his control, he contemplated invading Ming China, first securing control of Korea (Joseon at the time). When the Korean governors, vassals of the Emperor of China, rejected the proposed free passage agreements, he devised invasion plans starting in August 1591.

In April 1592, Japanese troops landed on Korean soil, capturing Seoul without significant difficulty and undertaking the takeover of the country’s strategic points, dividing to achieve this goal as quickly as possible before China reacted. In four months, they had begun to force a route to Manchuria by spring 1593. However, a Chinese army counterattacked and pushed the Japanese back to Seoul, where the war bogged down.

The quagmire of the Korean expedition destabilized Hideyoshi, and the birth of his first son in the same year sparked a succession dispute with his nephew, while the fierce repression of Christianity caused further troubles. A new invasion of Korea launched in 1598 failed miserably, and a plague epidemic ravaged the country, claiming Hideyoshi’s life on September 18, 1598. Once again, Japan was deprived of a leader.

The Tokugawa Leyasu Period (1543–1616)

Tokugawa Ieyasu, a longstanding ally of the Oda, had taken up arms against Toyotomi Hideyoshi since the latter was not an ally but a competitor. As far back as 1584, when the Tokugawa supported Oda Nobukatsu over Hideyoshi’s candidate in the succession to Nobunaga, the Tokugawa had been at odds with Hideyoshi and his kin. Ieyasu’s son became Hideyoshi’s adopted child when the two leaders settled their differences and established a united government.

While Hideyoshi consolidated power elsewhere in Japan, he made the Hojo stronghold of Kanto available to the Tokugawa in 1588. Quickly agreeing, Ieyasu saw the chance to extend his empire (from 5 to 8 provinces), while Hideyoshi wanted to undermine his competitor by relocating him to an area he did not control. Ieyasu won over the previous Hojo clan members and started constructing a new domain in Edo while patiently waiting for his opportunity.

After Hideyoshi appointed him and four other counselors as regents for his son Hideyori, he served in this capacity until Hideyoshi’s death in 1598. After Maeda Toshiie, the most revered of the five regents, was killed, Ieyasu spent a year forging alliances with Hideyoshi’s erstwhile opponents and then marched on Osaka Castle, where Hideyori was hiding.

Ishida Mitsunari rallied the other three regents to stand against him. It didn’t take long for the western army to become a clan that supported Hideyoshi and the eastern army to establish a clan that supported the Tokugawa clan. During the greatest battle in Japanese history in June of 1600, the Tokugawa clan marched north against the Uesugi clan and then west to counter the army marching to Fushimi, dividing its forces under the command of his son Hidetada. However, this secondary force fell behind along the Tokaido route and was therefore not present.

The Battle of Sekigahara took place on the 21st of October, 1600, and included around 160,000 troops. The battle was intense, but the Tokugawa ultimately broke through the western army’s right flank, resulting in a widespread defeat that allowed them to seize control of Japan and wipe out their competitors simultaneously. On April 24, 1603, after consolidating and solidifying his power, he was made shogun, marking the commencement of the last Japanese shogunate, which would continue for almost 250 years.

References:

- Hammer, Michael F.; Karafet, Tatiana M.; Park, Hwayong; Omoto, Keiichi; Harihara, Shinji; Stoneking, Mark; Horai, Satoshi (2006). “Dual origins of the Japanese: Common ground for hunter-gatherer and farmer Y chromosomes”. Journal of Human Genetics. 51 (1): 47–58. doi:10.1007/s10038-005-0322-0. PMID 16328082.

- Pierre François Souyri, Nouvelle Histoire du Japon, Paris, Perrin, septembre 2010, 627 p. (ISBN 978-2-262-02246-4, OCLC 683200336).