Navigating at sea is like navigating in the desert: Your only reference points are the positions of the Sun, the stars, and the planets. You need to keep track of your compass bearing and distance traveled and mark your position on a map. Perhaps the most surprising aspect of the history of navigation, or navigating at sea, is that until the 18th century it was impossible for explorers and sailors to accurately determine their position. Today, thanks to advances in navigation technology, it is possible to pinpoint a location with a margin of error of a few meters. So how did we get to this point?

Navigating at Sea

Early sailors calculated distances and directions based on specific positions on the shore or the positions of the Sun, Moon and stars. They kept their ships from stranding by measuring water depth using simple-sounding methods like weighted ropes. In short, they had no other means of navigating than using their sight. Instruments such as the magnetic compass, astrolabe, and sextant (measuring the angle of the Sun or a star on the horizon) allowed reasonably accurate estimates of direction and latitude at sea, but longitude remained a problem for a long time.

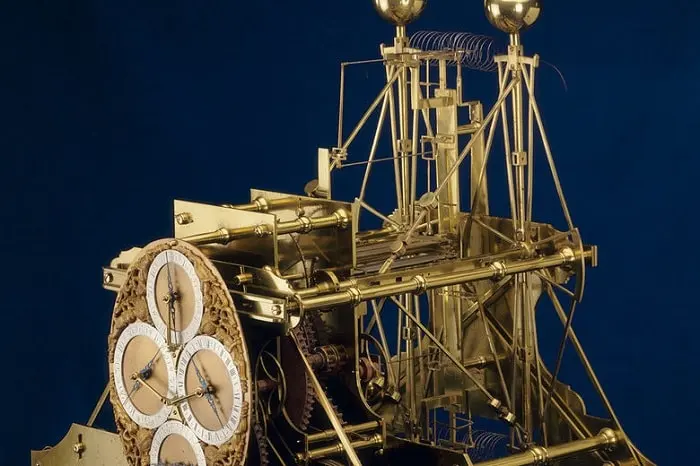

The calculation of longitude is based on comparing local time with “universal” time (it is Greenwich, England as of today). Those are linear time zones and each one-hour difference means a difference of 15 degrees in longitude. So calculating longitude at sea was not possible until John Harrison developed his chronometer in the 18th century. Until the chronometer, navigation had always been a problem. It was only in the 20th century with the development of the gyroscopic compass, radar, and, from the 1990s onwards, the global positioning system (GPS) resulted in major advances in maritime navigation.

Timeline of the History of Navigation

3000 – 1500 BC – First Sonars

Ancient Egyptians used reeds to create sound and measure the depth of water and estimate the distance from the shore.

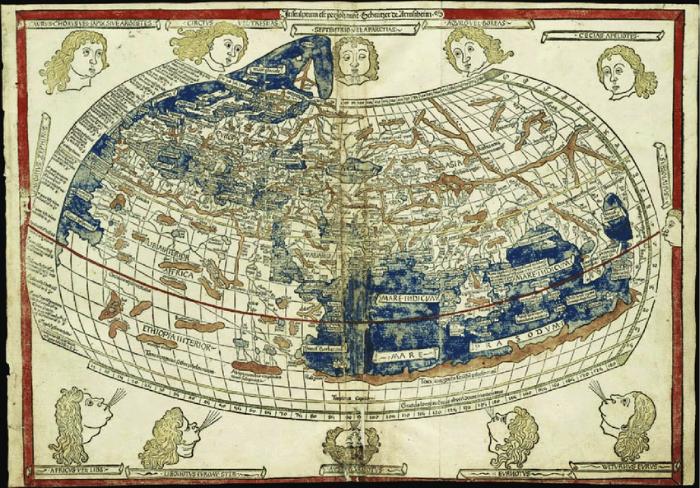

150 – Ptolemy’s World Map

Ptolemy (Claudius Ptolemaios), one of the first Romans living in Egypt, used a grid system to create a world map, which influenced nautical charts until the 17th century. Ptolemy formed a grid system of latitude and longitude lines as a reference for geographically locating known elements such as lands, coasts, islands, and towns on a map. Longitude was expressed in time zones, while latitude was indicated by the number of hours in the longest day of the year.

15th Century – Dead Reckoning

The hourglasses are used for the dead reckoning calculation: this tool allowed one to calculate the position of the ship by measuring the travel distance, time elapsed, and speed.

1100 – Compass

Chinese sailors were the first to use the magnetic compass (a magnetic needle is used to indicate north and south directions) for navigation which greatly advanced nautical navigation.

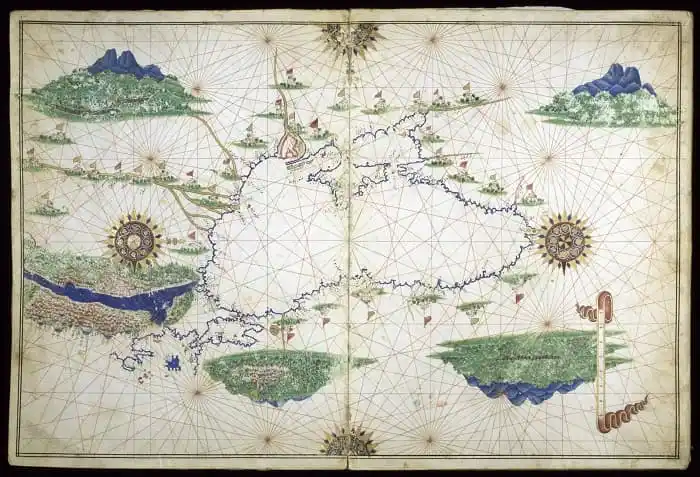

1300 – 1500 – Nautical Charts

Portolan (Italian for “related to ports or harbors”) nautical charts of the Mediterranean and European coasts allowed sailors to navigate from port to port using compass landmarks.

1480 – Astrolabe

Sailors began to use the astrolabe to estimate latitude by calculating the angle of the Sun or a particular star on the horizon. The astrolabe improved navigating at sea.

1753 – 59 – Chronometer

John Harrison makes his first chronometer, the H1, in 1735. He later developed further versions, producing the H4 in 1759. The chronometer was used to determine longitude at sea, enabling the measurement of the time at a known location and the time at the current position.

1907 – Gyroscopic Compass

The American Elmer Sperry invents the gyroscopic compass, which is a major advance in maritime navigation because it always points north and does not deviate.

1930s – 40s – Radar

The invention of radar made it possible to determine the position of an object even if it could not be seen.

Late 20th Century – Global Positioning Systems

Satellite-based GPS has made it possible to pinpoint locations and navigate at sea with a margin of error of a few meters.