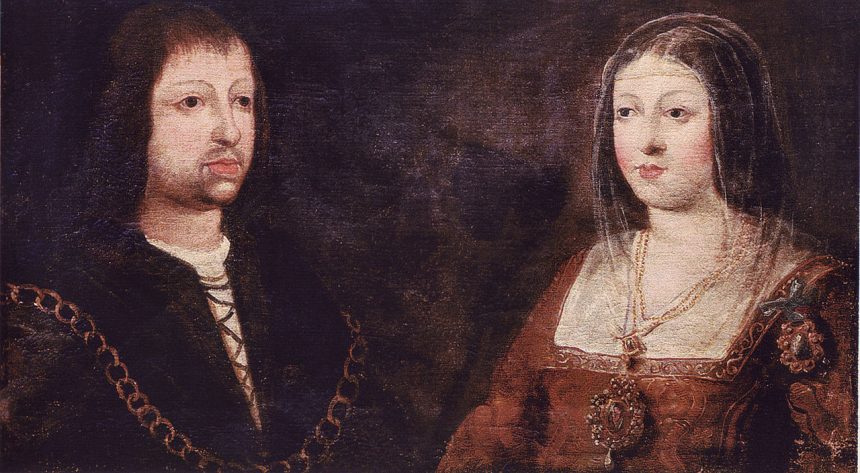

History of the Spanish Nobility in the 16th Century

The Reconquista, which ended in 1492, led to the rise of powerful noble families who had been granted lands and titles for their role in expelling the Moors from Spain. This solidified the status and wealth of the Spanish nobility entering the 16th century