The National Socialists used war games and the militarization of mass groups to shape young minds. The Nazi leadership dispatched many young individuals who had been raised under National Socialism to the front lines, where many of them died. “Not alone did the English drop bombs, but they also dropped ration cards (…). leaflets included, and they’re the unpleasant kind. My faith is unmovable. God will be with us, and our cause will be just if A. Hitler can lead us to victory. I just can’t bring myself to be hateful of the English. They are Germans, too.”

- The methods used by the Nazi government to brainwash its young citizens

- Inherently prepared to lay down their lives for others

- Fast-tracked military training

- In the front, the dads helped their kids with their assignments

- The top Nazis assemble a final posse

- A contrast between idealized notions of warriors and the harsh reality they face

In spite of the bombing of Berlin and other towns and the bleak news from the Eastern Front, 15-year-old Liselotte’s belief in “Führer, folk, and fatherland” remained unshaken on August 28, 1943. These journal entries were written by a girl, reflecting her thoughts and feelings about the war from 1942 to 1945 through the lens of a child raised in a National Socialist society.

After the Soviet loss at Stalingrad in February 1943, she wrote the following: “Germany is under severe distress now. Stalingrad. It’s sad enough to make you shed some tears. Still, I refuse to give in to weakness. That’s why we can’t afford to give up and admit defeat. The greatest of our German people have shed their blood at the front, and we dare not dishonor them in this way.” By November, however, the young people’s outlook had brightened once more: “Hitler gave me fresh optimism in triumph, he talked of landing in England and of retribution for the bombing horror.”

The methods used by the Nazi government to brainwash its young citizens

Diary entries like Liselotte’s show the extent to which the National Socialists were effective in indoctrinating and molding a generation of youngsters and young adults in accordance with their ideological ideals. A whole generation’s worth of kids grew up learning and believing in National Socialist slogans and concepts like duty and devotion.

They were raised to believe in Adolf Hitler and their “racial” supremacy. Moreover, as Nicholas Stargardt of Oxford University recounts in his book “Children’s Lives Under the Nazis,” many children were trained to have an inflated sense of responsibility, leading them to sacrifice themselves and others in the war’s last months. On the 8th of November, 1943, Liselotte questioned herself: “Is it not our holy responsibility to continue the fight? If Germany were to be completely destroyed, then our bravery would be on par. Also, if we all die, 1918 will be over. Adolf Hitler, I believe in you and the German victory.”

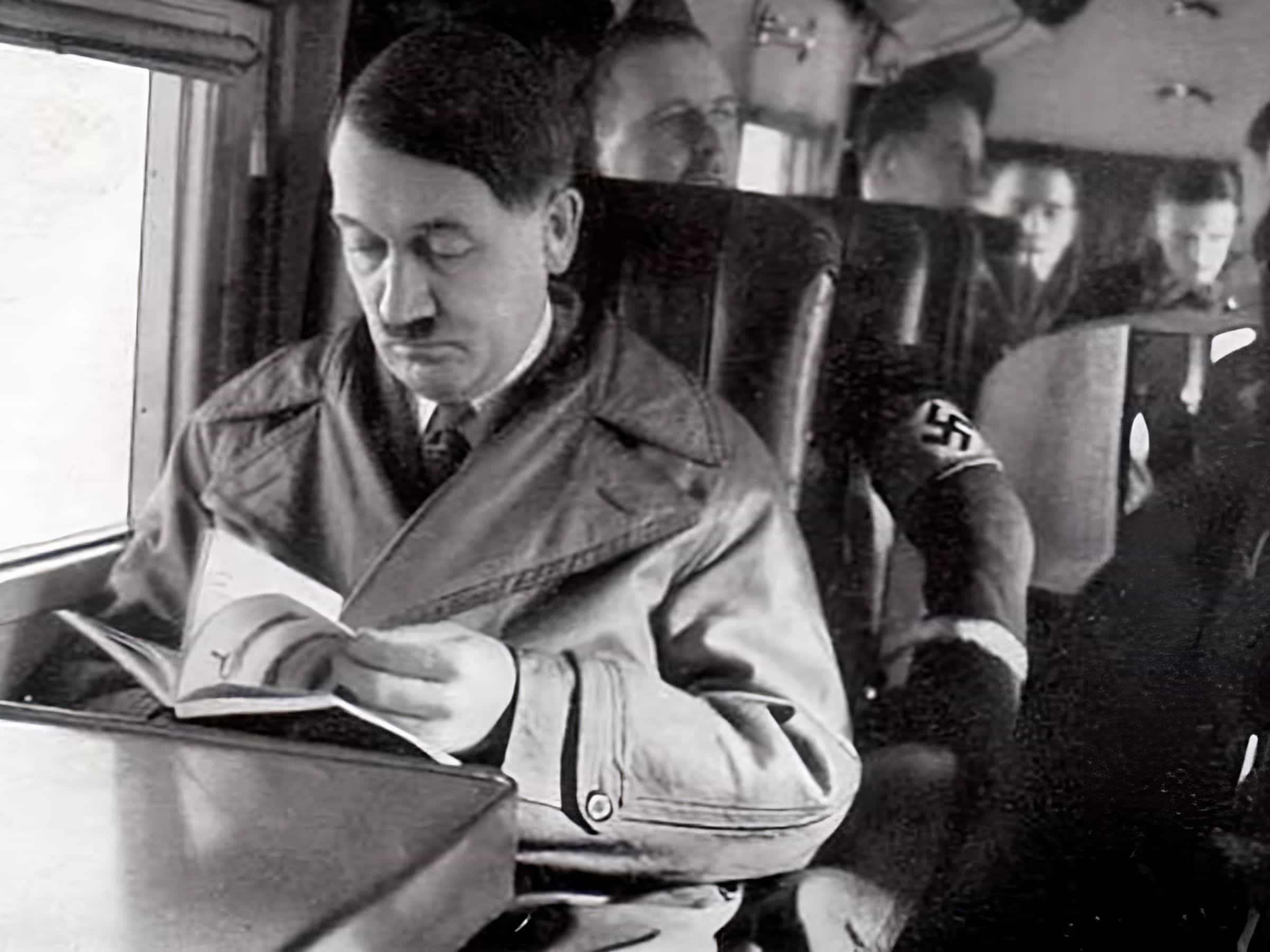

The Nazis aimed to instill their ideology in the brains of future generations as early as possible. They employed their youth groups for this purpose. The Hitler Youth (HJ) was the most influential of their youth groups. Its beginnings may be traced back to 1926. Beginning in the spring of 1940, all children ages 10 to 14 were required to join the Jungvolk and pledge loyalty to Adolf Hitler, making membership mandatory for all youths between the ages of 14 and 18 already in 1939.

The Jungmädelbund (JM) and League of German Girls (Bund Deutscher Mädel, BDM) were formed to represent and advocate for the rights of the girls. Virtually all German children and teenagers between the ages of 10 and 18 were members of the organizations since participation was required by law.

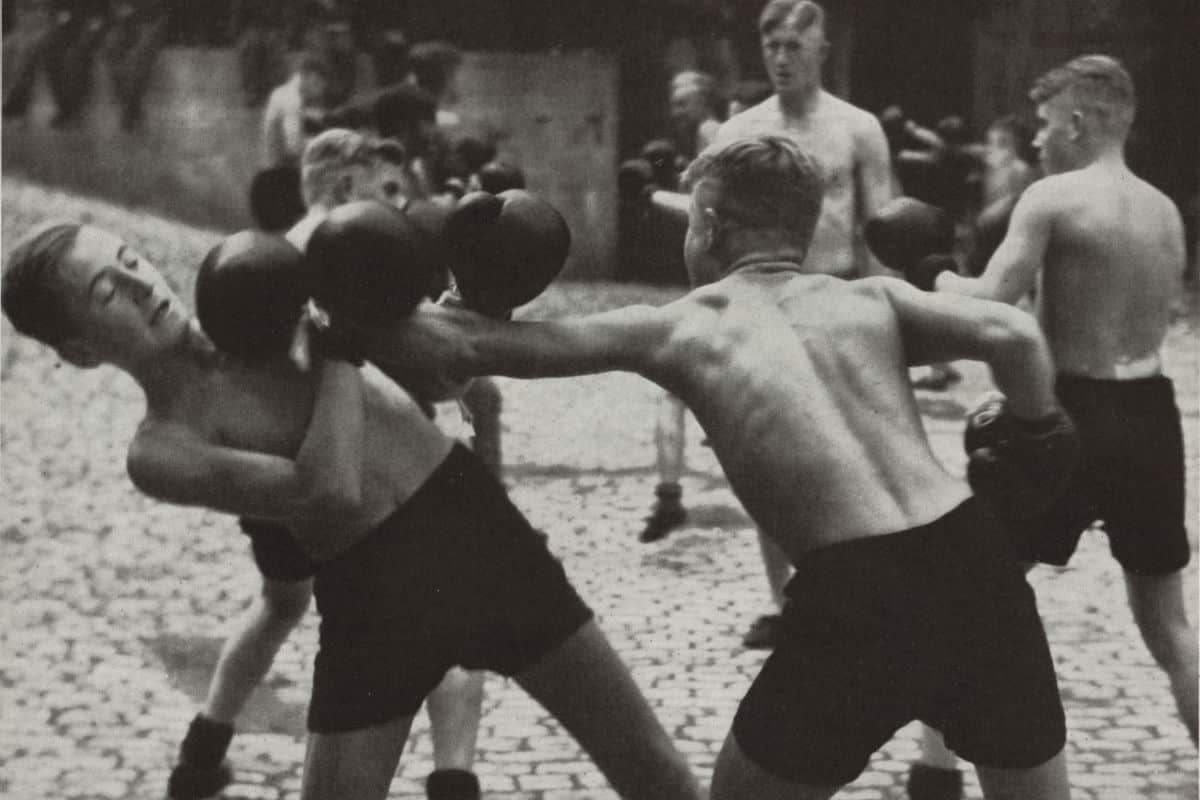

Additionally, in 1933, all other youth groups were outlawed as well. The idea was that the Nazi state would instill its ideology directly and offer paramilitary training for youngsters via physical exercise, rather than leaving instruction only to schools and homes. Hitler and the Nazi leadership relied on this kind of indoctrination to ensure their continued rule for the foreseeable future.

Topics like “Germanic Gods and Heroes,” “The People and Their Blood Heritage,” and “Adolf Hitler and His Fellow Fighters” were featured in the HJ units’ curriculum. Children were exposed to the age-appropriate propaganda radio broadcast at structured events including parades, field trips, and family night.

Children were tasked with gathering herbs from the woods and sorting through trash in the city, where they found items such as clothing, metal, and even bones. Girls knitted socks and mittens for troops at the front, assisted in kindergartens, and served food and coffee at railway stations to passing soldiers, many of whom the girls later corresponded with via letters.

Inherently prepared to lay down their lives for others

Some young people were tremendously drawn to the military because of the feeling of community it fostered, the appeal of a sense of duty, the uniforms, and the freedom they were promised once they were distant from their families and schools. Joachim Lörzer, a contemporary witness, recalls feeling quite mature in his HJ outfit at the age of twelve. According to him, in 1944, he was completely ready to give his life for “Führer, folk, and fatherland.”

Decades later, some kids said they didn’t care about politics because they were too busy hanging out with their pals and having fun. Others remembered the torturous drills that everyone had to do, while others felt a profound sense of idealism. Postwar interviews with former war children revealed widespread feelings of “betrayal” and “abuse” among those who, like Liselotte, had trusted the dictatorship and its promises. National Socialism gave them the false sense of superiority they needed to believe in their own uniqueness before sending them unprepared to their graves.

Fast-tracked military training

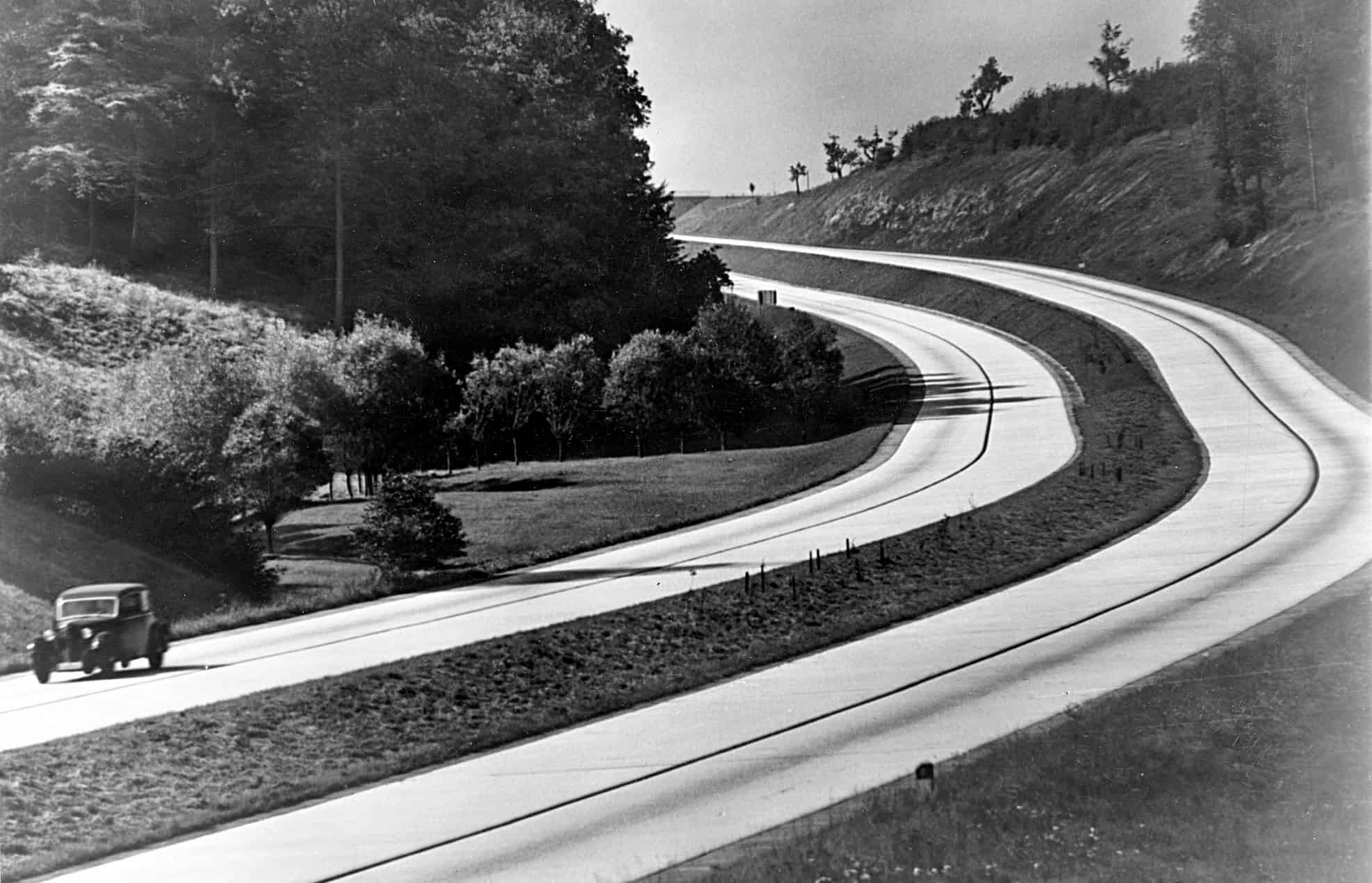

The militarization of youth was already visible by the time World War II broke out, but it grew more so after the war’s outbreak. Military training centers were established where any 15-year-old could be taught as a mini-soldier within three weeks, and the Hitler Youth’s shooting duties were increased. It wasn’t until 1943 that boys became common flak helpers.

The conflict shaped the future of Germany’s youth. Repeatedly, soldiers were seen making their way inside classrooms. In schools and other public buildings, students and visitors might see maps depicting the front lines. German kids chanted war poetry as they built model battleships in art class. Nazi propaganda films like “Our Flags Lead Us Forward” (Hitlerjunge Quex), with the revealing caption “A Film of the Sacrificial Spirit of German Youth,” were distributed to children as Christmas gifts. In the movie, a boy who is a firm believer in the HJ is killed by his “communist” companions.

In the front, the dads helped their kids with their assignments

Families were profoundly affected by Nazi ideology. The dads were in the thick of battle, but they kept in touch with their kids through field letters. They keep coming back to the same story of struggle in their letters to one another. Some dads encouraged their children in letters by telling them to “hold your own” and “be a strong, courageous German girl.” On the other side, we observe that dads serving overseas penned touching letters to their children, offering handmade gifts or helpful guidance for the future. Some of the letters include schoolwork that had been graded and returned to the parents by the children after being corrected by their dads.

The National Socialists attempted to inject their philosophy into the domestic sphere, but they were only partially successful. Historians note that there was a limit to the amount of time family conflicts could last. According to ex-BDM women, they never betrayed their own parents. However, there is still case-by-case data that contradicts the overall trend. There was a lot of love and support inside the family, even though everyone was a dedicated Nazi adherent.

The top Nazis assemble a final posse

Letters and diaries written by youngsters in the severe tone of Wehrmacht reports demonstrate the extent to which Nazi ideology permeated the world of children. In 1939, a 14-year-old wrote, “The industrial heart of Upper Silesia is almost completely in German hands, and the city of Lodsch has been taken. Führer in Lodsch.” German children became used to their putative leadership position, whereas children in the occupied areas of the East were taught to admire and follow the “Herrenmenschen” (“Master Humans.”)

A Polish BDM volunteer wrote home to her family, “They are insolent as nothing and gape at us like marvels of the world,” arguing that Polish youngsters should be forced to work. Another BDM girl described how, when she was a little child, her father had told her that the Poles, because of demographic shifts, would swiftly overrun the German Reich if nothing was done. To put it simply, she was terrified of this happening.

As the battle progressed and the Nazi regime’s ideology hardened, the regime’s true inconsistencies and relentless cruelty became clear. Nazi officials betrayed the same individuals they had praised for years as the “future of the people” by sacrificing them when defeat was certain. Formed in 1944, the Volkssturm enlisted all able-bodied males between the ages of 16 and 60 to fight in the “final victory.” The young people’s sobering experience stood in sharp contrast to their solemn allegiance to the Führer. Tools, training, and standard-issue garments were all in short supply.

There were only 40,500 rifles and 2,900 machine guns in the Volkssturm’s main arsenal by the end of January 1945. These weapons were a mishmash of primarily foreign and antiquated models, and ammunition for them was sometimes scarce. The lads were provided ancient, black SS uniforms from the pre-war years (…) and – especially unpleasant for 15-year-olds who wanted to prove what they could accomplish for the Fatherland – French steel helmets.

A contrast between idealized notions of warriors and the harsh reality they face

Günter Lucks, a Hamburger, was one of those deployed to the battlefront in Vienna. The 16-year-old had joyfully obeyed his reporting order to the Volkssturm. “I finally felt like an adult, like a real soldier in the making. And I was pleased to be of service to the Fatherland at this most important time.”

However, instead of excitement and chivalrous warrior romance, disillusionment and dissatisfaction swiftly set in. He told his mother on February 25, 1945, that he was sick of military training at the Reich’s camp at Lázn Luhacovice, Moravia. “You’re correct, I’d rather be in the post office 10 times over.” Following a brief period of training, Lucks led a group of HJ youngsters to the advancing front near Vienna.

Captain Otto Hafner was perusing a chart when Lucks and his company marched up. Subsequently, Hafner reflected, “They were boys, with babyish complexions and oversized field blouses. Their small fingers hid behind the long sleeves, the narrow faces under the far too enormous helmets. (…) It was a major worry of mine. Should I send these kids into battle against the Russians?”

When Günter Lucks fired his first shot, he was near Brno, and the experience was “surreal” for him. Unlike many of his companions, he made it through captivity until the conclusion of the war. Nearly 60,000 German boys aged 15 to 17 who were born between 1927 and 1929 lost their lives during the war, most of them as a result of conscription in 1944 and 1945. There were almost 1.5 million people in all cohorts from 1920 and 1929.

The brother of Liselotte was also enlisted in the Volkssturm. “Girls should also learn to use the Panzerfaust as Bertel has. They could hold her own against any tank.” In her diary for April 1945, Liselotte made an interesting observation. After waiting a few days, she finally put pen to paper and wrote: “Bertel was sent to the front lines only the day before. It breaks my heart to see boys as young as 15–18 riding out on trucks or bicycles, armed with a carbine, pistol, or bazooka. My heart swells with pride for our boys, who still charge the tanks when they hear the word. However, they are hastily being put to death.”

Liselotte’s journal shows that she has serious misgivings about the Führer and the government, even at this early stage. The revelation that the Nazis had executed Wehrmacht commanders was a turning point that led to this shift in view. The diary entry of April 12, 1945, says: “To hang a German, a Prussian officer! Curse them, curse the whole Nazi mob, these war criminals and murderers of Jews.” The girl makes one of the very few references to Jews. In their journals and correspondence, many Germans chose to remain quiet about what happened to the Jews.

It was on May 17, 1945, when Liselotte made her last note in her diary. She’d heard that Bertel and the rest of the HJs had all perished. The teen observed: “So many, many soldiers shirked and chickened out, but Bertel was much too enthusiastic for that. For whom then? For Hitler? For Germany? Poor, hardened youth!” A realization that arrived, sadly, too late.