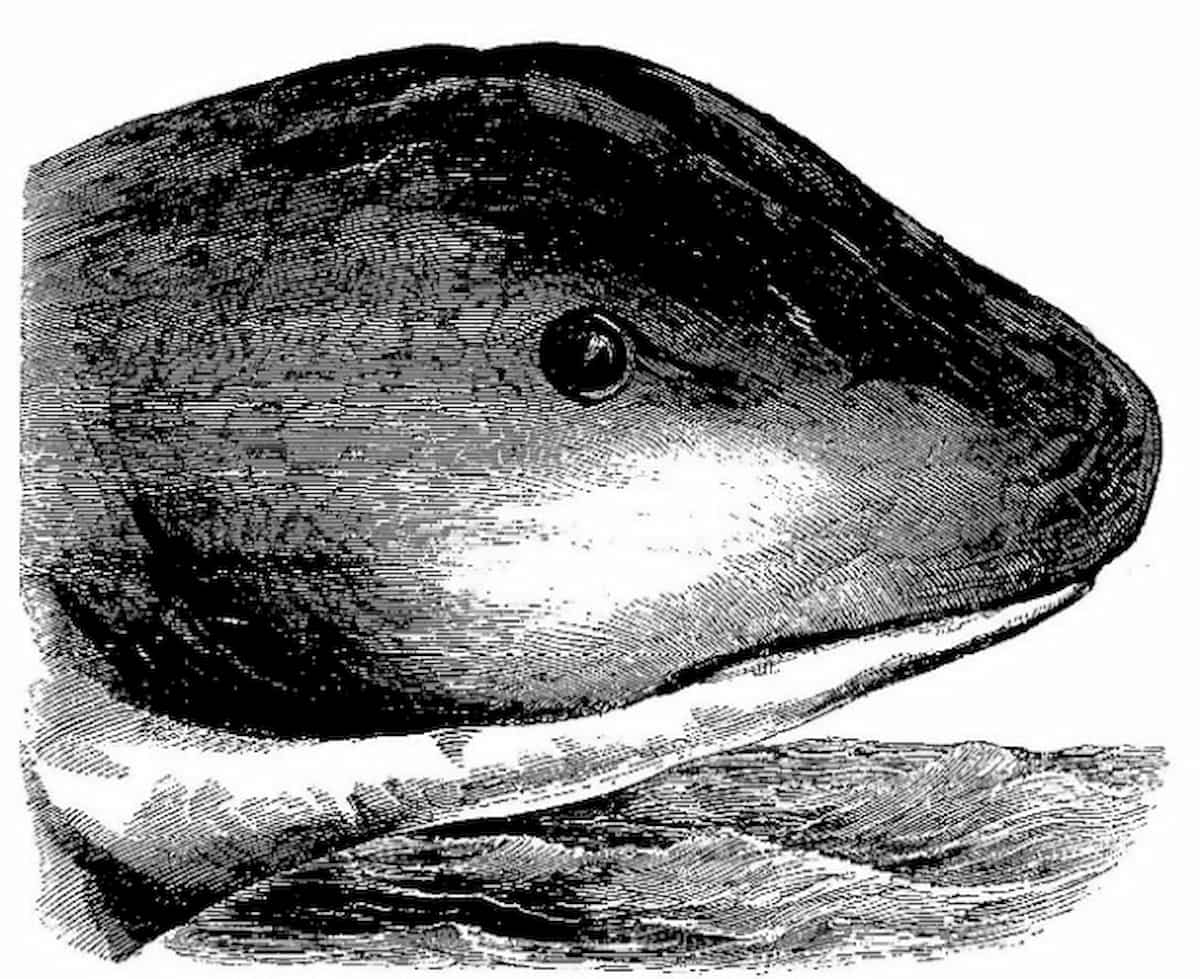

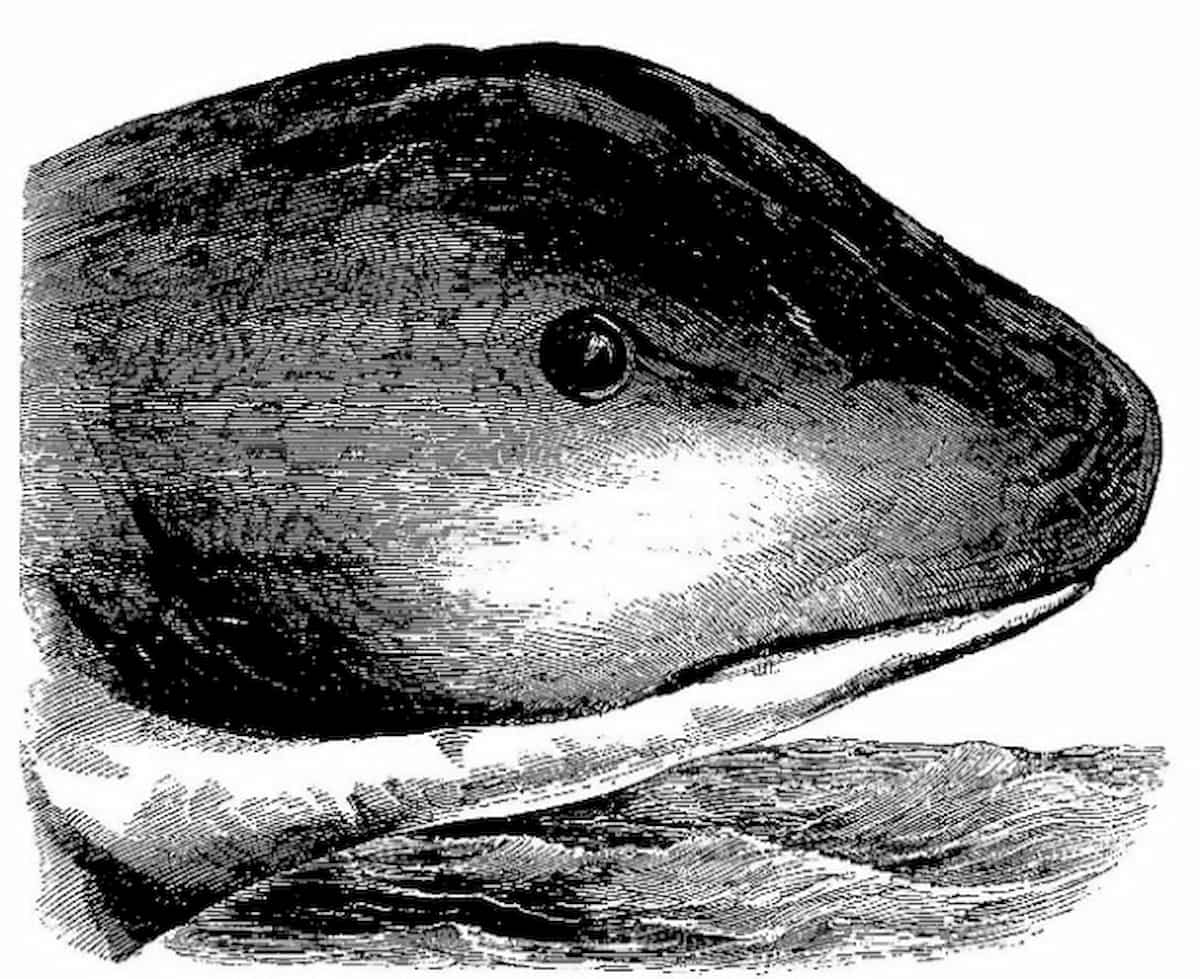

HMS Daedalus Sea Monster: Description and Accounts

Sea Monster of HMS Daedalus is an alleged cryptid that was said to have been observed by a British military ship.

Sea Monster of HMS Daedalus is an alleged cryptid that was said to have been observed by a British military ship.