The term “holodomor” (meaning “killing through famine”) has a morbid ring to it. Millions of Ukrainians died in 1932 and 1933 due to the man-made disaster known as the Holodomor. Those who made it through the ordeal will never forget what happened. Like Maria Katchmar, who, decades later, recalled what it was like to be a youngster in her town when the Holodomor struck:

- The Peasants Compelled to Work on Kolkhozes

- Situations for the Peasants Seemed Grim

- The Communists Did Not Care About Human Life

- A Ban Was Placed on the Farmers

- The Holodomor Was a Time When Many Individuals Prioritized Themselves

- During the Holodomor, People Began to Eat One Another

- The End of the Holodomor

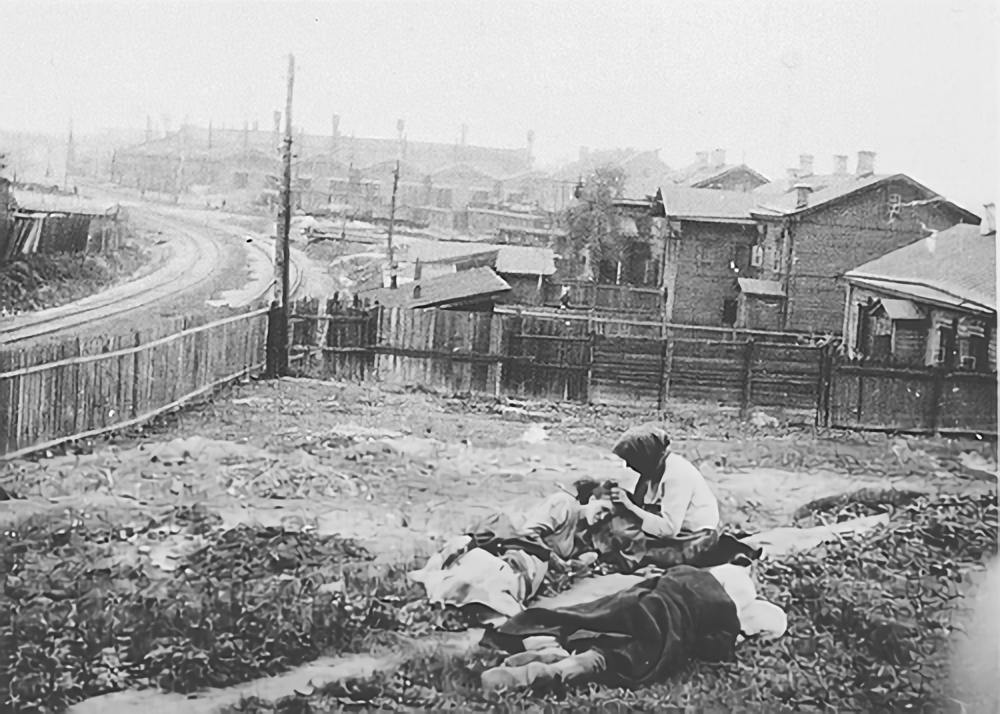

“There was absolutely nothing to eat. We ate grass. Mostly, we ate pancakes made of leaves and frostbitten potatoes that our neighbor gave us. (…) Almost everyone died. Most of the time, there was only one man or woman left [from each family]. Almost all the youngsters perished. (…) There was a pit, and there they threw them in, like mud. The pit was big enough for the whole village.”

16 countries and 22 US states, including Minnesota, have officially designated the Holodomor a genocide.

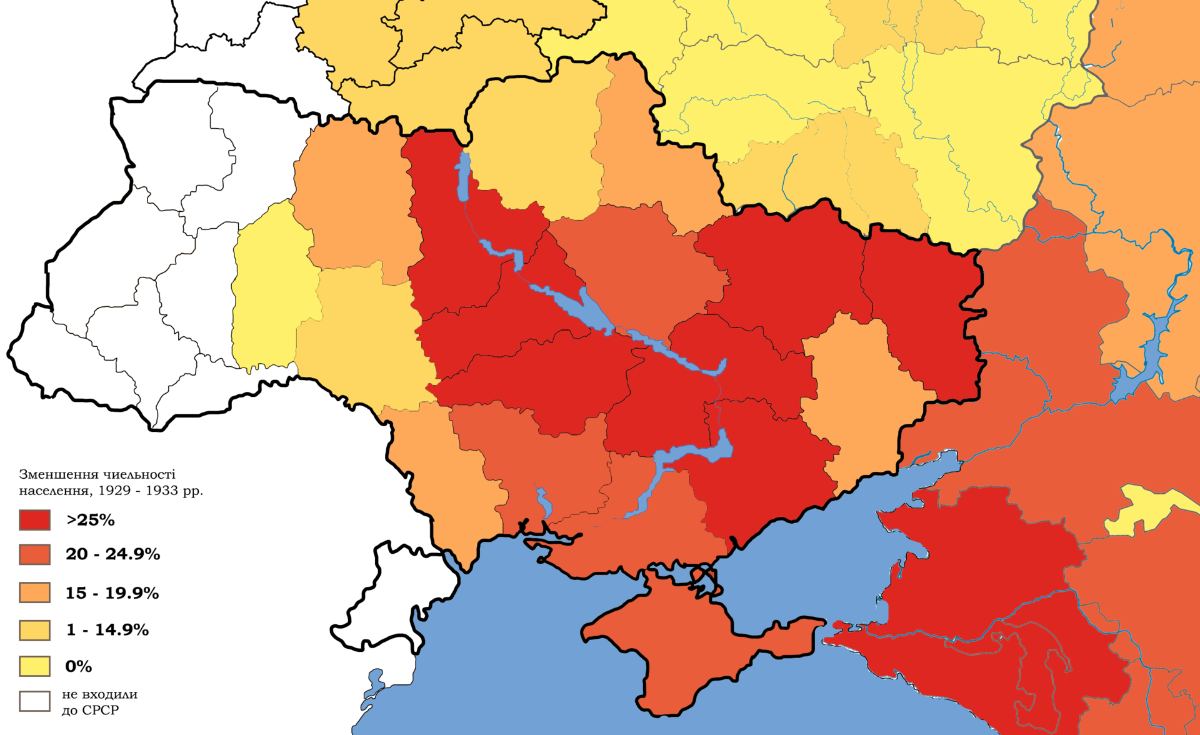

Polyvka was a settlement in the Ukrainian region of Cherkassy Oblast where Maria Katchmar spent her childhood. Many people, including Maria Katchmar’s eight siblings, perished from starvation there and in other Ukrainian towns and villages about 90 years ago. Recent research estimates that between 1932 and 1934, around 3.9 million Ukrainians lost their lives. At the time, this amounted to 13.3 percent of Ukraine‘s total population. At the same time, the famine decimated whole villages throughout the Soviet Union, including in Kazakhstan (where the death toll was disproportionately high), the Volga region, the North Caucasus, and other areas.

It is now generally accepted that Josef Stalin’s (1878–1953) “revolution from above” was directly responsible for the Holodomor. Causes include Bolshevik industrialization and modernization goals that were enforced harshly, unachievable high levies, and the forced collectivization of farmland.

The Peasants Compelled to Work on Kolkhozes

It was official violence and escalation that led to the famine in Ukraine, the breadbasket of Europe. The Bolsheviks, led by Stalin, have been cranking up the persecution of the peasants since 1928. Many peasants were coerced into selling their property and cattle to the government in 1929, when mandatory collectivization of farms (kolkhozes) was instituted. They were subject to food and meat quotas just like every other peasant.

When people rejected the Soviet government’s oppressive policies, they were labeled “kulaks,” a name from the tsarist period that referred to affluent farmers. That’s why Stalin said in a 1929 directive that they should be “liquidated as a class” since they were enemies of the revolution. And thus the “kulaks” were shunned, jailed, sent to harsh climates, or put to death.

Stalin’s plan with the search for the class enemy was to spread his state restructuring out into the countryside and disrupt the established order there. The Bolsheviks did not only see the peasants as a lower-class workforce necessary to feed the city dwellers. Nonetheless, the Bolsheviks were also certain that the rural masses would eventually rise up in rebellion.

Situations for the Peasants Seemed Grim

In 1929, peasant Semen Ivanisov lamented the helplessness of his circumstances, writing that he would be labeled an enemy as a “kulak” if he worked hard and enlarged his property. Because otherwise, only the poverty that was sanctioned by ideology would survive. Therefore, the Soviet leadership eliminated all incentives for increasing grain production.

To go where he wanted to go, Stalin cheaply accepted the annihilation of his own people.

Official records originally reported an increase in grain yields in 1930 compared to 1929, a year when terrible weather persisted and people suffered from famine. This was despite the haphazard rearrangement of agriculture. The leadership in Moscow, however, was so confident in the success of collectivization that it made a disastrous decision: they increased the levy quotas for both the communal farms and the remaining independent farmers.

It was already clear that crops would fall well short of estimates by 1931. The Kremlin learned of the communal farms’ inefficient practices, poor yields, and malnourished people. Even though at that time, almost everyone knew that collectivization was to blame for decreased harvests, the program could not be questioned because of its association with Stalin.

The Communists Did Not Care About Human Life

It didn’t take long to choose a victim. The failure to meet the quotas was blamed on the “kulaks,” who were subverting the system, and on the inept bureaucrats, who were not cracking down hard enough on the peasants. Moscow boosted quotas for 1932 despite knowing that many were already hungry, as Bolshevik reasoning dictated that this was necessary to offset the peasantry’s supposed anti-Soviet obstructionism.

In the eyes of the Communists, human life was not all that important. To get what they wanted, they were willing to take the cheap option of mass murder. The goal was to maximize resource extraction from the areas and maintain a steady rate of population growth.

Stalin’s opinion that nationalism and peasantism were intimately related influenced his decision to escalate the fight against the peasants. In 1925, Stalin said, “The peasant question is the basis, the quintessence of the national question,” adding that a strong national movement would always be supported by a peasant army and that if one wished to halt such a growth, one had to begin with the peasants. For this reason, Stalin saw the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, with its huge rural population, as a special threat. Stalin’s choice may have been influenced by the bloody conflicts that broke out between peasants and Bolshevik forces between 1918 and 1920.

The absurd targets were attempted to be met by authorities in the spring of 1932 by collecting massive quantities of grain, while being under severe strain. They sent troops to search the towns for supplies. In a letter, a Ukrainian farmer from Sobolivka described the process thusly: “The authorities do the following: they send the so-called brigades, who come to a man or a farmer and search everything so thoroughly that they even pierce the ground and walls with sharp metal tools, into the garden, into the thatched roof, and if they find only half a pound, they take it away on the horse and cart.”

As of August 1932, stealing even a little quantity of food was punishable by death or 10 years in a work camp in the Soviet Union.

A Ban Was Placed on the Farmers

Punishment was similarly harsh for farms that fell short of their targets. Communities as large as farms, ranches, and even towns were singled out and punished monetarily for engaging in commerce. The government took all of the food, equipment, and possessions.

As a result of widespread famine, Ukrainians attempted to leave for cities and other countries, but the Bolsheviks blocked the borders and briefly halted the sale of railroad tickets. To begin with, towns instituted a passport system to exclude the sick and poor farmers. Fugitive hunters set out on patrol.

Due to extreme desperation in the spring of 1933, people started eating whatever they could get their hands on, including horses, turtles, cats, rats, frogs, dogs, and ants.

Stalin’s belief that “Ukrainian nationalism was to blame for the insufficient grain supply, that Ukrainians were therefore purposefully resisting the central power and should be punished once and for all” justified the brutality with which the regime knowingly and willingly drove people to starvation. Stalin wrote to his close friend Lazar Kaganovich on August 11, 1932, saying, “If we do not attempt to repair the situation in Ukraine now, we may lose it.”

If, as some historians believe, the hunger was not deliberate, the Bolsheviks nonetheless used it to further their own agenda. In a cynical way, the starvation served the purpose of dominance quite well. The people were regimented, opposition was crushed, and it was abundantly apparent who had the power over life and death.

The Holodomor Was a Time When Many Individuals Prioritized Themselves

As a result, starvation did not affect everyone equally. Even in the countryside, supply chains were organized in hierarchies, and states were not necessarily the ultimate arbiters of food distribution and rationing. It reminds many of the Soviet Union, when one person was in charge and everyone else just followed orders. However, the complexity of the problem became clear during the Holodomor. Decisions were influenced by the actors’ personal interests at every level. That included anything from favoritism in the allocation of food from communal fields to outright hostility against social outcasts.

Horses, dogs, cats, rats, ants, turtles, and frogs were all consumed by hungry humans in the spring of 1933. They ate moss, acorns, and tree bark, and fried pancakes made from leaves and grass. Some of the locals cooked the leather off their belts and shoes and ate it. Mykola Latyshko, a contemporary witness, told how every day in the spring of 1933, a hearse would drive through the streets and men would ask, “Did someone die over the night?” at the doors of random homes.

Another author, Pavlo Makohon, described the situation in his village in the Dnipropetrovsk region at the time: “I ran around collecting everything I could get—porcupines, meat from dead horses—and brought it home to them [the siblings],” he said in a video released by the Ukrainian Interest Group of Canada. “When there was nothing left and everyone had starved to death, I realized that I, too, would die. So I left and started wandering around the ‘khutory’ [homesteads]. Black flags were hanging on the homesteads because everyone had starved to death. In our village, two children were eaten, but the rajon [administrative unit] authorities closed the case.”

During the Holodomor, People Began to Eat One Another

Cannibalism incidents soared in the early spring of 1933. The Soviet OGPU recorded many cases of “starving family members killing weaker persons, usually youngsters, and using their flesh for food” in the region of Kharkiv. There were 9 instances of cannibalism in March of 1933, 58 in April, 132 in May, and 221 in June. During the Holodomor between 1932 and 1933, the Ukraine saw at least 2,505 people convicted of cannibalism. Those unfortunate enough to be spotted munching on human flesh were mercilessly thrashed by the mob, and some were even burned to death.

Ukraine’s social fabric was shattered along with the bodies and minds of its famished citizens by the severity of the crisis. Theft, homicide, and general lawlessness all rose. People in the same community or with the same family did not trust one another. Many individuals, according to those who saw this phenomenon, put their own concerns first and paid little attention to the plight of others.

Additionally, many people’s social connections were the sole reason they made them. Joining a communal farm and getting aid from family and friends might be the difference between life and death. Being close to the system boosted one’s chances of survival, therefore, very frequently, just one individual in a position of power could rescue a whole family.

The End of the Holodomor

The Bolsheviks did not lessen their grip on the peasants until collectivization was officially finished in 1933, by which time there were almost no farmers remaining to bring in a harvest. The Holodomor ended in the autumn of 1933, when deaths began to slow down. The Soviet authorities suppressed information about the famine for a long time.

The Holodomor has become well known and recognized as an important aspect of Ukrainian history and national identity. Ukrainians usually remember the victims of the Holodomor on the last Saturday of November. The subject of whether or not Stalin actively sought the extermination of the Ukrainian people is a point of contention among experts. Ukrainian historians are in no doubt that Stalin committed genocide, although many Russian scholars emphasize the Soviet context of the famine, noting that not just Ukrainians but members of other ethnic groups inside and outside of Ukraine perished.

In the West, there is a range of professional views on this topic. The Holodomor famine’s aftereffects were unquestionably genocidal. There were a shocking number of fatalities. The Holodomor became a true genocide in certain areas. It’s always important to consider motive when discussing genocide. Both the legal evaluation and the historical context are important. Germany is only one of several countries that have expressed a desire to officially label the famine Stalin produced as genocide.

Yet, there is little doubt that Stalin intentionally starved the Ukrainian peasants to death by removing their access to their land and other sources of income, notwithstanding the ongoing debate about the legal evaluation in light of the UN Genocide Convention. Stalin used the Holodomor not only as a means to repress the peasantry, but also to crush forever any hope of independence or even partial independence for the Ukrainian people. Now we know that plan failed.

- Argentina, Australia, Canada, Colombia, the Czech Republic, Ecuador, Estonia, Georgia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Mexico, Moldova, Paraguay, Peru, Poland, Portugal, Ukraine, the Vatican City, and Romania are the countries that have acknowledged Holodomor as genocide.

Bibliography

- Lubomyr Luciuk, Lisa Grekul, 1953. Holodomor: Reflections on the Great Famine of 1932–1933 in Soviet Ukraine. Kashtan Press. ISBN 978-1896354330.

- Institute of National Remembrance (2009). Jerzy Bednarek, Serhiy Bohunov, Serhiy Kokin. Holodomor. The Great Famine in Ukraine 1932–1933 (PDF). ISBN 978-83-7629-077-5.

- National Museum of the Holodomor. “Website of the National Museum of the Holodomor”.