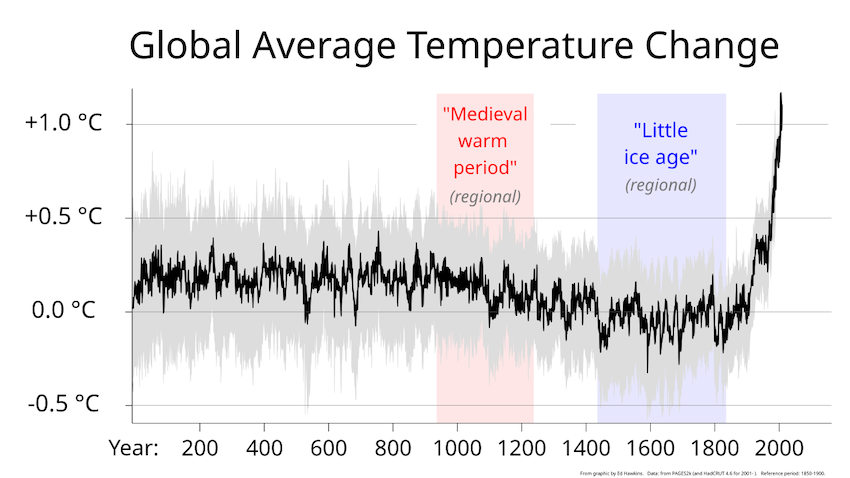

For about 500 years, from 1300 to 1850, with a peak in the 17th century, Europe experienced a Little Ice Age. In a time when society was predominantly agrarian, European countries, particularly France, endured severe famines. This article explores the phenomenon and its sometimes unexpected consequences.

The Paradox of the Term “Little Ice Age”

The expression “Little Ice Age” is paradoxical because, despite the prolonged cooling, most of the continent did not turn into an icy wasteland inhabited by woolly rhinoceroses.

“The average temperature was about 1 to 2°C lower than today. It was a significant cooling of the climate, but not a true Ice Age. Even Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie acknowledged that the term was somewhat exaggerated,” explains Pascal Acot, an epistemologist and author of Histoire du climat (History of Climate), published by Perrin.

When discussing the Little Ice Age, the name of French historian Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie is inevitably mentioned.

When the Glaciers Advanced

Le Roy Ladurie popularized the concept in the late 1950s in the journal Annales, adapting a term first used by American glaciologist François Emile Matthes, who applied it to Atlantic climate changes 500 years before our era.

As a specialist in the early modern period, Le Roy Ladurie sought to understand the bleak 17th century, marked by famines (1693–1694 and 1709) and revolts. In the absence of reliable temperature measurements before the early 18th century, he relied on indirect evidence, such as:

- Dendrochronology (tree-ring studies, where thinner rings indicate colder years).

- Grape harvest dates, as early or late harvests provide key climate indicators.

- Glacier movements, particularly in the Alps, where historical records and artwork from the 1590s show significant glacial expansion, signaling a cooling trend.

By compiling these data, Le Roy Ladurie defined the Little Ice Age as a global cooling period between 1303 and 1859, with average temperatures 1 to 2°C lower than today. Winters became longer and colder.

Although a 1°C drop may seem minor, when sustained over decades, it had dramatic consequences. For example, in Chamonix, glaciers advanced by nearly a kilometer, engulfing villages in their path.

-17°C in Marseille in Louis XIV

The Little Ice Age was felt across Iceland, Scandinavia, and even beyond Europe, affecting North America and China. It was a global phenomenon, likely caused by increased volcanic activity, variations in solar radiation, and—though still debated—early human impact on the environment.

The Little Ice Age was not a uniform period of cold. Following Le Roy Ladurie, other climate historians such as Christian Pfister and Franz Mauelshagen identified different phases:

- A relatively mild period between 1530 and 1564

- A colder phase from 1565 to 1629

- A particularly severe cooling from 1688 to 1715

- A temporary warming, followed by another cold phase starting in 1740

Available data highlight the 17th century as particularly harsh, with winter temperatures on average 1.1°C lower than those between 1971–2000. Between 1680 and 1700, January temperatures fell below zero in eight different years, compared to only two between 1980–2000, and three between 1880–1900.

The 17th Century: At the Heart of the Little Ice Age

How did this impact daily life? In agrarian economies, climate fluctuations had direct consequences. The late 17th and early 18th centuries, coinciding with the personal rule of Louis XIV, saw three major famines:

- 1661

- 1693 (1.3 million deaths out of a population of 20 million)

- 1709 (630,000 deaths)

A cold winter alone did not guarantee a failed harvest. The worst combination was a cold winter followed by a rainy summer, leading to widespread crop failure. Wars worsened the situation. The 1709 famine struck at a time when Louis XIV’s armies were struggling. In December 1708, the weather was unusually mild, and winter wheat had already begun to sprout. However, in January 1709, temperatures plummeted:

- January 5: 10.7°C in Paris

- January 6: -3.1°C

- January 13: -23.1°C

Even southern France suffered, with Marseille recording -17°C on January 17. Contemporary accounts describe:

- Birds freezing mid-flight

- Tree trunks splitting open

- Church bells cracking due to the extreme cold

Even the royal court at Versailles was affected. Saint-Simon wrote:

Everyone is shivering in the château. Wine freezes in carafes, ink solidifies at the tip of the quill. Poor-quality oat bread is served to Madame de Maintenon. The king, a hunting enthusiast, avoids going outside.

A March on the Bastille…

Outside the royal court, many peasants did not even have oat bread. A chronicler noted:

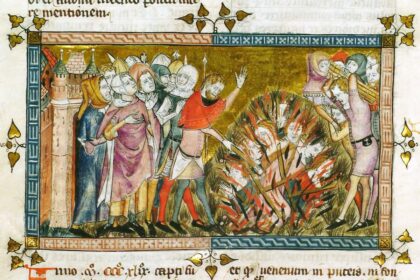

“People are making bread with acorns, roots, and sawdust.”

Some even resorted to making fern soups. As in the Middle Ages, cases of ergotism (“Saint Anthony’s Fire”)—caused by consuming contaminated rye—reappeared. In one year alone, about 200 food riots erupted, a record number.

Historian Gauthier Aubert, author of 1709, l’année où la Révolution n’a pas éclaté (1709, the Year the Revolution Didn’t Happen), described the period as: “1709 was like 1789 in fragments.”

He explained:

The Parisians marched on the Bastille but did not take it. People discussed assembling the Estates General, but it never happened… The key difference from 1789 is that the French elites held firm. The state did not collapse.

Crisis and Modernization

The 17th century, the peak of the Little Ice Age, also marked Europe’s transition into modernity. In response to these severe climatic challenges, societies sought new agricultural solutions:

- Artificial fertilizers were developed to reduce dependence on unpredictable weather.

- Radical environmental transformations became more common.

Historian Geoffrey Parker suggests that the divergence between China and Europe, which became evident in the early 19th century, was already forming during the Little Ice Age. While Europe responded with a scientific and technological revolution, China remained stagnant, waiting for better times.

Estimated Temperature Changes in European Cities During the Little Ice Age

- London, England

- Winter temperatures frequently dropped below freezing.

- The Thames River froze multiple times, particularly during the late 17th century.

- Estimated temperature drop: 1-2°C (1.8-3.6°F) below modern averages.

- Paris, France

- Winters were harsh, with the Seine River freezing over.

- Estimated temperature drop: 1-1.5°C (1.8-2.7°F) below modern averages.

- Amsterdam, Netherlands

- Canals and rivers froze regularly, allowing for ice skating and winter festivals.

- Estimated temperature drop: 1.5-2°C (2.7-3.6°F) below modern averages.

- Zurich, Switzerland

- Alpine glaciers advanced significantly, encroaching on farmland and villages.

- Estimated temperature drop: 1.5-2°C (2.7-3.6°F) below modern averages.

- Berlin, Germany

- Winters were long and severe, with frequent snow and ice.

- Estimated temperature drop: 1-1.5°C (1.8-2.7°F) below modern averages.

- Rome, Italy

- Cooler and wetter conditions were observed, though less severe than in Northern Europe.

- Estimated temperature drop: 0.5-1°C (0.9-1.8°F) below modern averages.

- Madrid, Spain

- Winters were colder than usual, with occasional snowfall.

- Estimated temperature drop: 0.5-1°C (0.9-1.8°F) below modern averages.

- Stockholm, Sweden

- Winters were extremely cold, with the Baltic Sea freezing over.

- Estimated temperature drop: 2-3°C (3.6-5.4°F) below modern averages.

- Prague, Czech Republic

- Winters were harsh, with frequent freezing of the Vltava River.

- Estimated temperature drop: 1.5-2°C (2.7-3.6°F) below modern averages.

- Vienna, Austria

- Winters were long and cold, with significant snowfall.

- Estimated temperature drop: 1-1.5°C (1.8-2.7°F) below modern averages.