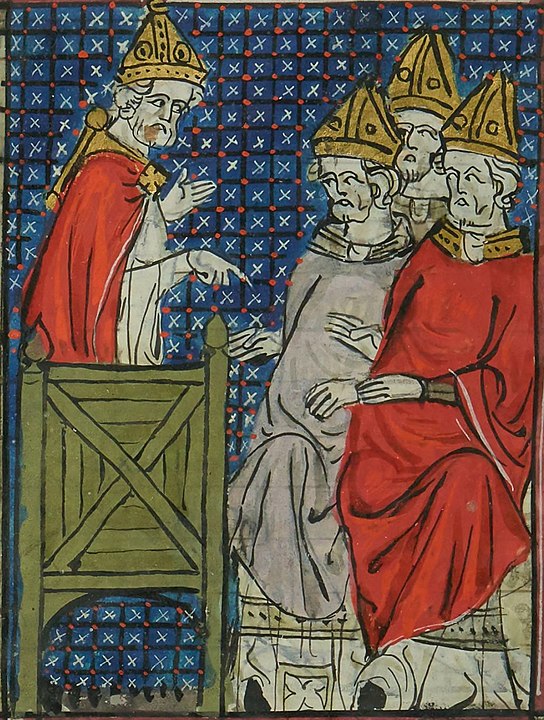

At the beginning of 1095, the Synod of the Church, headed by Pope Urban II, met in Piacenza. Hundreds of bishops came to the Italian city to talk about the papal reform. The goal of the reform was to stop secular authorities from meddling in the Church’s life and to raise the status of the clergy. The Byzantine Emperor Alexius I Komnenos sent a delegation to the same council to ask for help against the Seljuk Turks. At the time, the Seljuk Turks were powerful Asian conquerors who had already taken over many Byzantine lands in Asia Minor and Armenia and were almost to Constantinople.

- Pope Urban II Calls for a Holy Army

- Was the Pope’s First Crusade Speech Real?

- The Relationship Between Pope Urban II’s Call and the Church Reform Movement

- The Pope’s Effort to Make Turcophobia Acceptable

- “The Greatest Way to Show Love for Friends Is to Die for Them” (John 15:13)

- Byzantium Had Its Own Major Problems

In a preaching delivered in Piacenza, Urban II urged the Latins to help the Eastern Christians and the Byzantine emperor free themselves from the oppression of the Muslims.

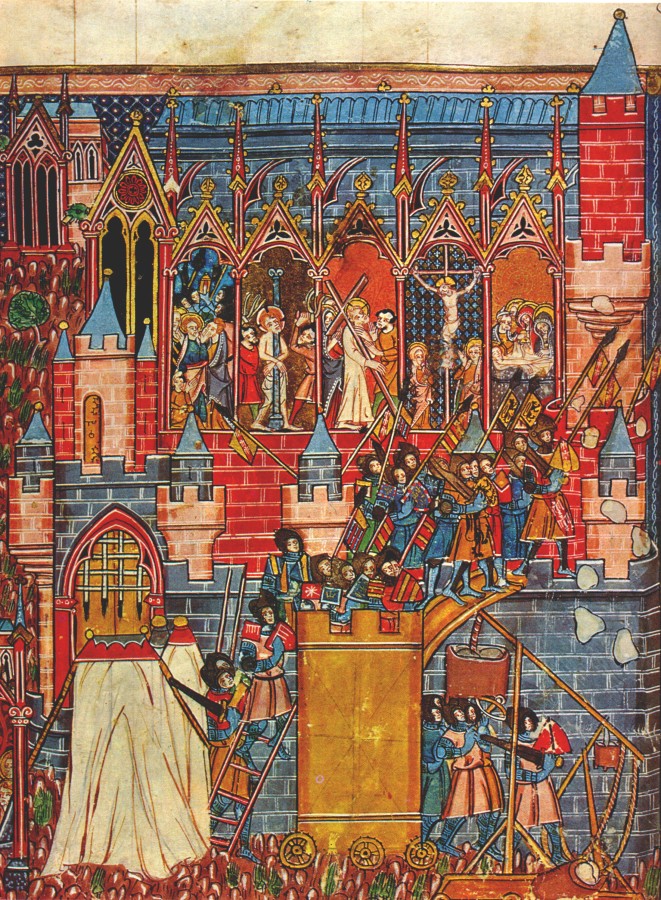

Pope Urban II Calls for a Holy Army

After the synod in Piacenza, the pope traveled with a retinue of prelates to northern Italy and France, where he paid a special visit to the abbey of Cluny, a stronghold of ecclesiastical change and the place where he had served as abbot.

Along with Count Raymond of Toulouse, he conferred with the local priest, Adhemar of Le Puy, in Saint-Gilles and in Le Puy-en-Velais. At Le Puy, Pope Urban II made the decision to call a church council, which met in Clermont on November 27 and featured the renowned preaching he would later give. Since there were so many people in attendance, Pope Francis gave his address to the gathering in the countryside, far from the confines of the city.

Urban II, after again detailing the plight of Eastern Christians, urged the audience to combine against the “pagans,” put an end to the fratricidal wars, and travel East to free their Christian brethren and retake their rightful lands. As a surprise, the pope also referenced Jerusalem in his statement, calling on Christians to free the sacred city and its sites, along with Constantinople.

With cries of “God wills it!” (“Deus vult!”) Seized by pious impulse, thousands of people responded to the pontiff’s call. Adhemar of Le Puy’s acceptance of the cross from the hands of the pontiff established a precedent. That was such a thoughtful and lovely gesture. The prelate was chosen to serve as the pope’s representative in the eventual military.

Christians listening to the pope’s homily pledged to join the “Holy army” and march to the East to battle heretics, and many of them sewed red crosses on their right shoulders to show their devotion. The Pope has promised those who take part in the upcoming campaign a pardon, putting them under the protection of the Church and giving them special rights.

Was the Pope’s First Crusade Speech Real?

The First Crusade, as it would come to be known, thus starts. We are still attempting, more than 900 years later, to figure out what the pope said in his homily. There are four distinct versions of the Pope’s address to the Council of Clermont, and they all seem to have been penned after the fall of Jerusalem in the First Crusade.

What really happened? Do we know if the pope’s response to the Byzantium emperor’s pleadings was premeditated or impromptu? How do the pope’s goals and those of the common people line up? It’s possible that the solutions to these queries can be discovered by looking at the context in which these events occurred.

The Relationship Between Pope Urban II’s Call and the Church Reform Movement

It is impossible to think about Pope Urban II’s call without thinking about the spiritual renewal that the Latin Church went through in the second half of the 11th century. At this time, the Reformed movement began as a response to the fact that the church was becoming more secular, that its authority was being mixed with that of the world, and that its moral authority was falling as a result.

At that time, the Church still had a lot of feudalistic tendencies. For example, bishops got land from secular sovereigns, especially the German emperor, in exchange for agreeing to be their vassals. The same emperor also thought it was possible to choose abbots and bishops, and the papacy was dependent on secular authorities.

The aim of the Reformers, who opposed such tendencies, was to purify and spiritually renew the Church and to strengthen the power and authority of the papacy.

They called for the freedom of the church (libertas ecclesiae)—that is, for the complete liberation of the church from the administration of the laity by the distribution of church offices, for the displacement of the secular aristocracy from the sphere of church administration.

It cannot be said that this program of freeing the Church from the influence of secular power was shared by most of the highest Western prelates. Many bishops of the Christian West resisted change, and the monastic world, which relied on the authority of the Holy See, became the agent of reform.

Inspired by monastic ideals, the leaders of the movement demanded the restoration of church order and strict adherence to church discipline and sought to restore the Church’s lost spiritual control over the minds and souls of the faithful.

Entire abbeys were removed from the authority of local bishops and placed under the direct authority of the Pope, the Vicar of St. Peter. The Congregation of Cluny, directly subordinated to the pontiff and attracting both reformers and ascetics, was the main support of the papacy in its rivalry with secular power, and Clunian abbots became frequent guests in the Roman Curia.

Under Pope Gregory VII (1073–1085), who actually inspired the ecclesiastical transformation, the reform movement evolved into a struggle for investiture (the right to appoint to church offices), a conflict between the German emperor and the Roman pope over supremacy so characteristic of the entire Middle Ages.

In the Dictate of the Pope of 1074, Gregory VII justified the pontiff’s spiritual leadership over the entire Christian world and asserted to himself the right to appoint bishops, convene councils, exercise supreme judicial power, etc.

The struggle for investiture began as a discussion of reform but quickly developed into a direct confrontation between secular and spiritual authority, so that Pope Gregory VII first conditionally and then actually deposed the German Emperor Henry IV by excommunicating him.

The Pope’s Effort to Make Turcophobia Acceptable

Even though Urban II was a devoted follower of the Cloister Reformation and a strict Gregorian, the fight between the pope and the emperor, between “priesthood” and “kingdom,” did not end. When Urban II became Pope, not all German bishops accepted his authority. In fact, most of Germany and northern and central Italy, including Rome, sided with the anti-pope Clement III.

Urban II reached out to both the West and Byzantium for help during this time. The pope had been in talks with Alexius I Komnenos about improving ties between the Roman Catholic Church and the Eastern Orthodox Church of Constantinople, and even about obtaining armed support in the fight against the Turks, since the very beginning of his papacy.

Urban II definitely had a plan, but he didn’t have the courage to ask the Eastern Christians for help until November 1095, after the success of the Cluniac Reforms. After the council in Piacenza, Henry IV’s son Conrad, who had turned against his own father, became a vassal of Urban II while traveling through France.

Urban II called on people to protect Christians and give them back their land. He also led the Christian world, even though he didn’t recognize Henry IV as emperor.

Against this background, the pontiff was almost at the top of secular and spiritual power, and his preaching at the Council of Clermont was an important political move in the fight for investiture. So, the fight for the liberation of the Latin Church (libertas ecclesiae) and the conflict between the papacy and the emperor led to the desire to free the Eastern Church and start the Crusades.

Cluniac Reformers, led by Urban II, shifted their focus from achieving Church freedom to freeing their Eastern Christian brothers and sisters. Thus, the struggle for the liberation of the Latin Church (libertas ecclesiae) and the conflict between the papacy and the emperor set the stage for the subsequent struggle for the freedom of the Eastern Church and the commencement of the crusading movement.

In the wake of the battle for the freedom of the Church, Urban II led the Cluniac Reformers to also fight for the freedom of their Eastern Christian brothers and sisters. Cluniac Reformers, led by Urban II, fought for the freedom of Eastern Christians as a natural extension of their fight for the freedom of the Church.

In his speech at the Council of Clermont, Urban II did not fail to speak of the sufferings that the Eastern Church is experiencing because of foreigners.

The Pope wished to influence his hearers and make his appeal more persuasive, and to this end, he described the misery of the Eastern Christians: Muslims conquer Christian lands, destroying everything with fire and sword, obstructing pilgrims, destroying churches, and mocking Christian shrines: “They overturn altars, profaning them with their impurities; they circumcise Christians, pouring the blood of circumcision on altars or baptismal fonts.

“Your brothers who live in the East,” the pope said in his speech, “are in dire need of your participation, and you must hasten to help them, for, as many of you have heard, the Turks have attacked them and conquered the Romanian territories as far as the shores of the Mediterranean.” In his preaching, Urban II linked the two themes of the need to help Byzantium and the insult to Christian sanctuaries. Thus, the coming expedition to the East was seen as “The work of God.”

“The Greatest Way to Show Love for Friends Is to Die for Them” (John 15:13)

The very idea of liberating the Eastern Church from the Turks was expressed by the pope in the language of Christian ethics, speaking of Eastern and Western Christians as “friends” and “brothers,” saying, “Our brothers, members of the body of Christ, are beaten, oppressed, and oppressed. Your half-brothers are born of one mother. Your sons are of the same Christ and the same Church.”

The war for their deliverance was seen as a good thing because, in the words of Urban II, “The greatest way to show love for friends is to die for them” (John 15:13). In his preaching, the pope viewed aid to the East as an expression of love for one’s neighbor, the central ethical value proclaimed by Christianity. The pope invited the laity, especially the knights, to go to the East and fight with arms in their hands against the Muslim oppressors of Christians.

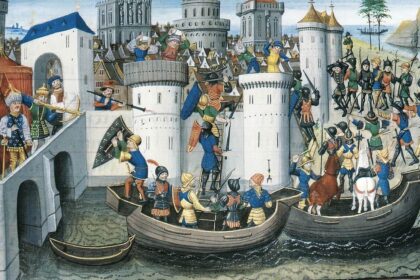

Was this exactly the kind of support Byzantium expected from the West? The emperor was indeed asking for military aid. The fact is that the Byzantine Empire had to constantly fight against many enemies: the advance of the Seljuk Turks into Asia Minor and the raids of the Pechenegs and Cumans. To do this, she needed somewhere to recruit new soldiers for her army.

She often recruited them from Western knights, especially the bellicose Normans—the descendants of the Vikings—who had chosen the Archangel Michael, the leader of the heavenly army, as their patron. Seeking happiness in foreign lands, the Normans served the pope and the Byzantine emperor with equal fervor, but very soon they began to pursue their own policies and drove the Byzantines out of southern Italy.

After the Battle of Manzikert in 1071, in which the Seljuk Turks inflicted a serious defeat on Byzantium, it had to make considerable territorial concessions. In addition, she was forced to defend herself against the Norman princes who ruled in Southern Italy, the former mercenaries of the empire, who now posed a threat to her.

Under these circumstances, Alexius sought an ally in the pope and hoped for help from Western knights to fight against her enemies. According to Western chroniclers, the Byzantine emperor supposedly wrote, exaggerating the colors, about the outrages of the Turks in Byzantium and the oppression of Christian pilgrims to Count Robert I of Flanders, who in 1090 made a pilgrimage to the Holy Land and, returning from Jerusalem, stopped in Constantinople, promising Alexei to send 500 mercenaries.

Byzantium Had Its Own Major Problems

In fact, the idea to ask the pope to call for Western soldiers to serve the emperor might have arisen even earlier. It is known that in 1074, as a result of an exchange of embassies between Rome and Constantinople, Gregory VII personally urged the Western Knights to go to the aid of the “Christian empire”.

He promised that he himself, as “commander and pontiff” (dux et pontificus), would lead an army and go to the East to fight against the enemies of Christ and reach the Holy Sepulchre.

But these plans were not to be fulfilled: the pope quarreled with the Eastern Roman Empire and even approved the invasion of Byzantium by the Normans.

In 1089, a new round of negotiations began between the Pope and the Greeks, during which both sides tried to enlist each other’s support (the Pope against the Emperor and the Grand Duke against the Normans), and already at the church councils in Piacenza and Clermont, the Pontiff was exhorting the West to liberate the Christian East.

Let us stress: Byzantium did not call for a crusade; the emperor was only interested in military support for the empire from the West. The Byzantine state’s war with the Turks was of a defensive nature; it did not take the form of a religious war.

None of the Eastern Christians demanded that they be liberated, and neither were the pilgrims oppressed by the Seljuk Turks. But the ill-informed Latins took almost literally the stories of Byzantine and Western travelers about the oppression of Christians, and in the mind of the pope, under the influence of Byzantine requests for mercenaries, the idea was born of an entirely new armed expedition to the East by Western knights, which, he said, would be a service for Christ and a defense of the Christian faith and Christians.

Bibliography

- Asbridge, Thomas (2012). The Crusades: The War for the Holy Land. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9781849837705.

- Barker, Ernest (1923). The Crusades. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-84983-688-3.

- Cahen, Claude (1969). “Chapter V. The Turkish Invasion: The Selchükids.” In Setton, Kenneth M.; Baldwin, Marshall W. (eds.). A History of the Crusades: I. The First Hundred Years. Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press. pp. 99-132.

- Cahen, Claude (1968). Pre-Ottoman Turkey. Taplinger Publishing Company. ISBN 978-1597404563.

- Becker, Alfons (1988). Papst Urban II. (1088-1099) (in German). Stuttgart: A. Hiersemann. ISBN 9783777288024.