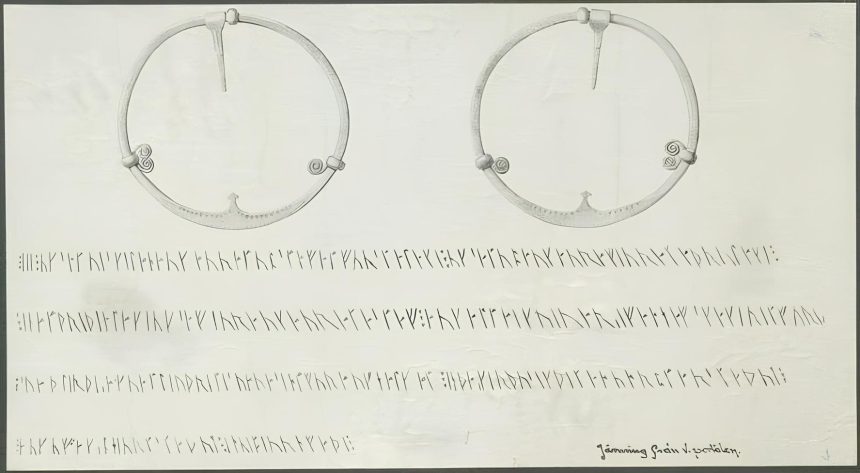

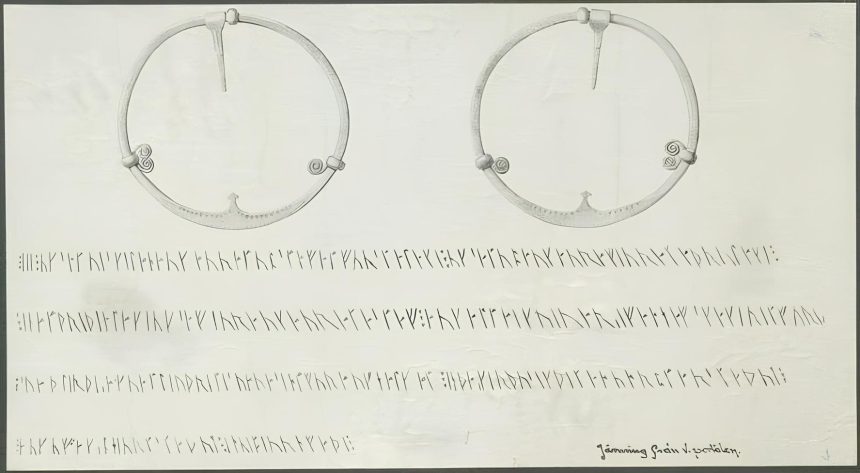

How Did the Vikings Calculate Fines?

A new translation of the historic Forsa Ring, one of the oldest Viking documents, suggests that the system for paying fines was more flexible than previously thought

A new translation of the historic Forsa Ring, one of the oldest Viking documents, suggests that the system for paying fines was more flexible than previously thought