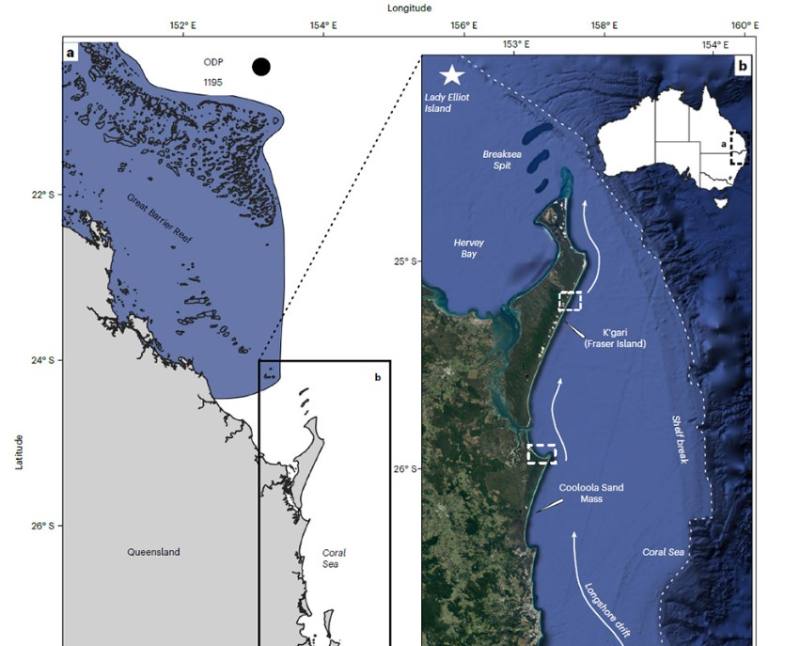

No one knew when or how the Great Barrier Reef was developed until today. In recent years, experts have come closer to finding the solution. They conclude that only after Fraser Island was established, between 1.2 and 0.7 million years ago, could the world’s greatest coral reef have developed. Since then, this hook-shaped, protruding sand island has kept the alluvial sand from washing up on the reef. This has let the corals settle without being disturbed.

Australia’s Great Barrier Reef is the world’s longest coral reef at over 1,430 miles in length. However, it has been unknown when exactly this rare and species-rich UNESCO World Heritage Site came into being. It is estimated that 25 million years have passed under the current tectonic and geological settings. Eastern Australia’s shelf region has been sufficiently far north to sustain tropical corals for the last five million years.

The Great Barrier Reef, however, was very recently constructed, maybe as recently as 450,000 years ago, according to radiocarbon analysis of reef sediments. If so, then what’s causing the hold up?

An island as a sand barrier

Daniel Ellerton of Stockholm University have looked at a different component of reef formation—sand transport—in an effort to find the solution. This is because an excess of washed-in sand prevents reef growth by preventing coral from settling. The team says that Fraser Island, located to the south of the Great Barrier Reef, is a crucial part of this equation.

The island, which protrudes like a hook from the Australian coast, is a component of a large area of sandbars and dunes that forms a barrier. About 120,000 cubic miles of sand are washed in every year by the prevailing currents off Australia’s east coast and carried north along the coast, eventually reaching the Great Barrier Reef.

In contrast, Fraser Island’s protrusion directs this current to the edge of the continental shelf, protecting the reef from sand influx.

Alteration about 1,2 million years ago

Having Fraser Island there would have been essential to the development of the reef. How long, though, has this sand island been here? Collecting sediment cores from various parts of the island and the nearby Cooloola sandbank, and then dating them using optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) is one way to find it.

In this way, scientists determined how long it has been since the sand grains were last exposed to sunlight before they became part of the sand islands.

Thus, it was between 1.2 and 0.7 million years ago when sand islands and dune fields first appeared. A great deal of sea level change occurred during that period due to the expansion and contraction of glaciers during the first ice ages. This also altered sand movement and ocean currents off the coast of eastern Australia. Changes in sea level shifted sediment on the continental shelf.

Fraser Island and the adjacent sandbars and dunes formed as a result of this process of progressively greater sediment loads piling up along the shore.

Essential precondition for reef development

It appears that this was the deciding factor in the Great Barrier Reef’s creation. This is because the formation of the barrier slowed the movement of sand to the north, making life for corals more conducive in the region of the present-day reef. The Great Barrier Reef’s southern and central parts couldn’t have formed without first forming Fraser Island.

This may also shed light on the unexpectedly late formation of the world’s biggest coral reef, which would have been impossible based on merely geological and climatic factors alone. These discoveries significantly alter our understanding of coastal sedimentary systems.