In the 19th century, shopping was almost the only available physical activity for women, and they threw themselves into it passionately in the department stores and arcades that filled European and North American cities.

Sports had obvious masculine connotations, and gender roles were clearly defined: what was allowed for men was not always permitted for women. Engaging in sports was considered contrary to feminine nature. For example, in 1797, Scottish doctor and moralist John Gregory wrote in “A Father’s Legacy to His Daughters“:

But though good health be one of the greatest blessings of life, never make a boast of it, but enjoy it in grateful silence. We so naturally associate the idea of female softness and delicacy with a correspondent delicacy of constitution, that when a woman speaks of her great strength, her extraordinary appetite, her ability to bear excessive fatigue, we recoil at the description in a way she is little aware of.

A Father’s Legacy to his Daughters, by John Gregory

Good health was seen as something vulgar and unworthy of a refined feminine nature, reducing a young woman’s chances of marriage—particularly in the bourgeoisie, even more so than in the aristocracy, as the bourgeoisie adhered even more strongly to the fashion of frailty and delicacy associated with high status.

By the 1860s, women began playing croquet alongside men. This is particularly noteworthy because the sport allowed young ladies and their potential suitors to meet and socialize not only in churches, ballrooms, and theaters. Croquet was followed by ice skating—ladies in hats and long skirts performed incredible maneuvers on the ice rinks.

In the 1870s, after croquet and skating, tennis became popular. Historian Eduard Fuchs wrote: “If mothers once took their daughters to balls, now they sent them to play tennis or ski. Winter resorts began to function as international marriage markets, while in summer, this role was taken over by all the parks and courts of major cities where tennis was played.”

Around the same time as tennis, women began to engage in team sports like football and hockey, leading to debates about appropriate sportswear for women. Men did not have these issues: their everyday attire was practical and quite suitable for sports activities.

The debates were heated; supporters of clothing reform even began suggesting that women should adopt trousers—the foundation of men’s wardrobes and a symbol of masculinity.

Several reform proposals for women’s clothing were made. For example, American suffragist Amelia Bloomer, editor of the feminist newspaper “The Lily,” invented “bloomers” in the early 1850s—a costume consisting of Turkish-style pantaloons worn with a shortened dress. Naturally, such experiments provoked sharp criticism from conservatives.

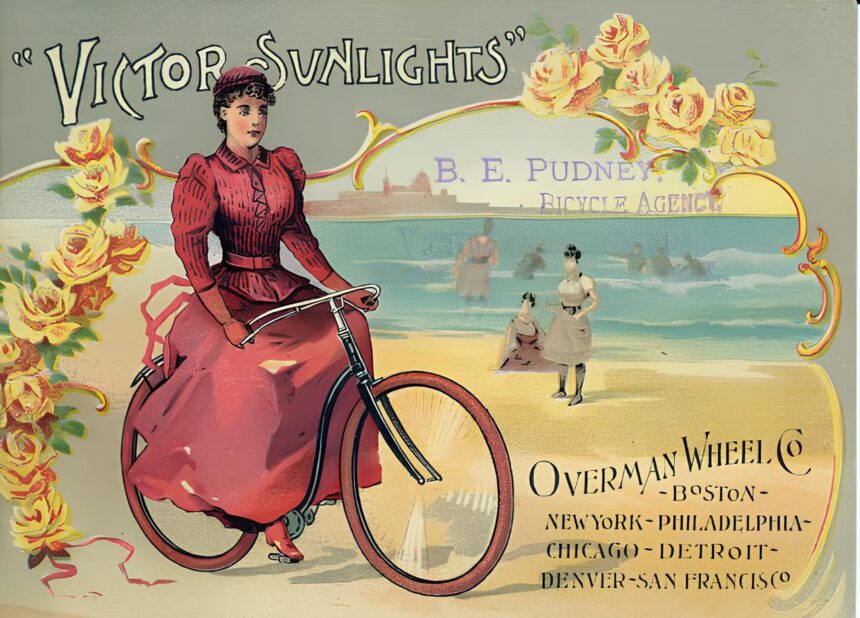

Debates about appropriate clothing for women became even more intense after the introduction of the so-called “safety bicycle” in the 1880s. The bicycle brought revolutionary changes to the lives of both men and women. Unlike other sports that women adopted after men, cycling was a fundamentally new activity for both sexes. Bicycle rides made women much more visible participants in the public life of the city. Many, like the protagonist of Chekhov’s “The Man in a Case” (1898), were horrified by these newfangled iron machines, which women rode astride—a sight deemed highly improper: “I was horrified yesterday! When I saw your sister everything seemed dancing before my eyes. A lady or a young girl on a bicycle — it’s awful!

” But the new mode of transportation also had many supporters:

“The dawn has come… thanks to the bicycle, the hour of women’s liberation has struck. Discovering a wonderful world… turning the wheels of her bicycle, the independent girl of our time strengthens her health and develops her mind… How limited life seems before the arrival of the bicycle!”

— Louis Jay, from an article for “The Lady Cyclist,” 1895

One of the British cyclists and active participants in the movement for dress reform (or the rational dress movement), Lady Florence Harberton, proposed a special women’s cycling costume with breeches in 1881. In the magazine “Punch,” which consistently mocked the rational attire of contemporary women, a 1895 cartoon showed two ladies, one wearing a cycling costume and the other a traditional dress. Their conversation went like this:

“Gertrude: ‘Jessie, darling, why are you wearing a cycling costume?’

Jessie: ‘To wear it, of course.’

Gertrude: ‘But you don’t have a bicycle!’

Jessie: ‘But I have a sewing machine!'”

Most female cyclists preferred traditional ladies’ attire, which caused them quite a bit of trouble while riding. Female athletes chose to injure their bodies with corsets, get entangled in ankle-length skirts while playing, and suffocate in long-sleeved blouses while holding their mandatory hats, unwilling to change into more comfortable sportswear that might include Turkish pantaloons or culottes.

The need for special sports clothing for women became apparent only a couple of decades later when sports, initially unfashionable and unladylike, suddenly began to influence the development of everyday fashion, which increasingly focused on practicality, functionality, and comfort.

Designers like Jean Patou, Elsa Schiaparelli, and Gabrielle “Coco” Chanel became trendsetters in the 1920s by launching their sports lines.

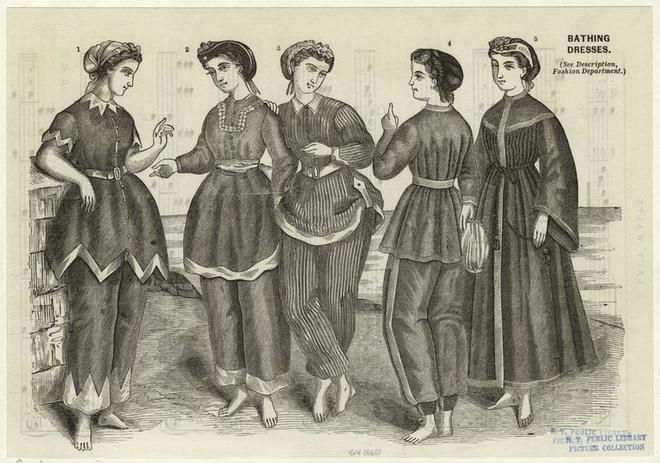

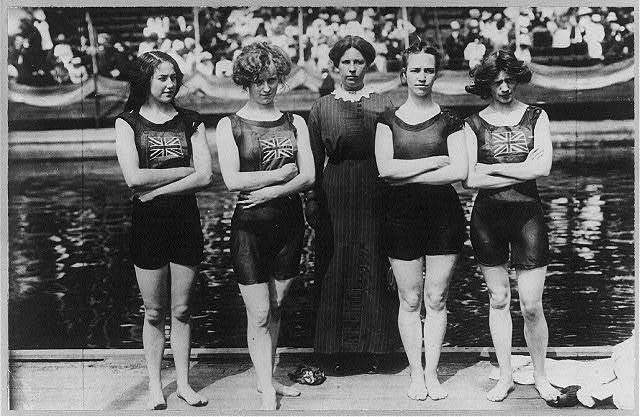

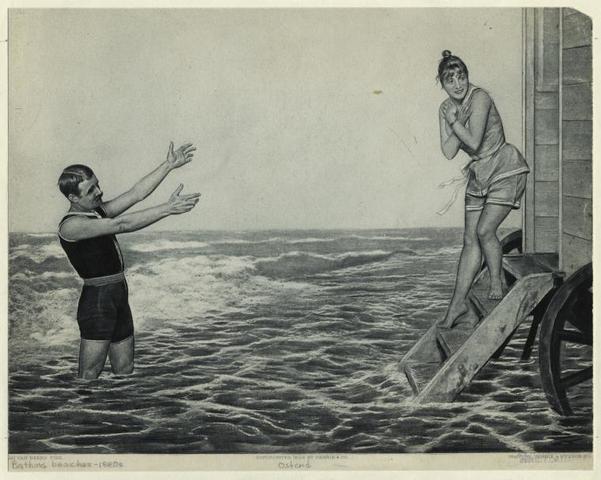

Even swimwear, which resisted any innovations the longest, underwent changes only at the beginning of the 20th century—with a shift in attitudes toward bathing and tanning. Now, having a tan was perceived as a sign that a person had the time (and money) to sunbathe, and open swimsuits became fashionable. Before that, swimwear was a complex construction that completely covered the body—with a corset, pantaloons, blouse, cap or hat, and swimming shoes.