Hussars, Cuirassiers and Dragons Under Napoleon

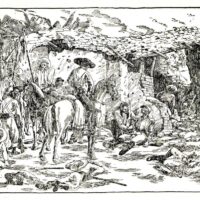

Napoleon's Grande Armée included a wide array of cavalry units, each with specialized roles and distinctive characteristics. Among the most famous types of cavalry were the Hussars, Cuirassiers, and Dragoons.