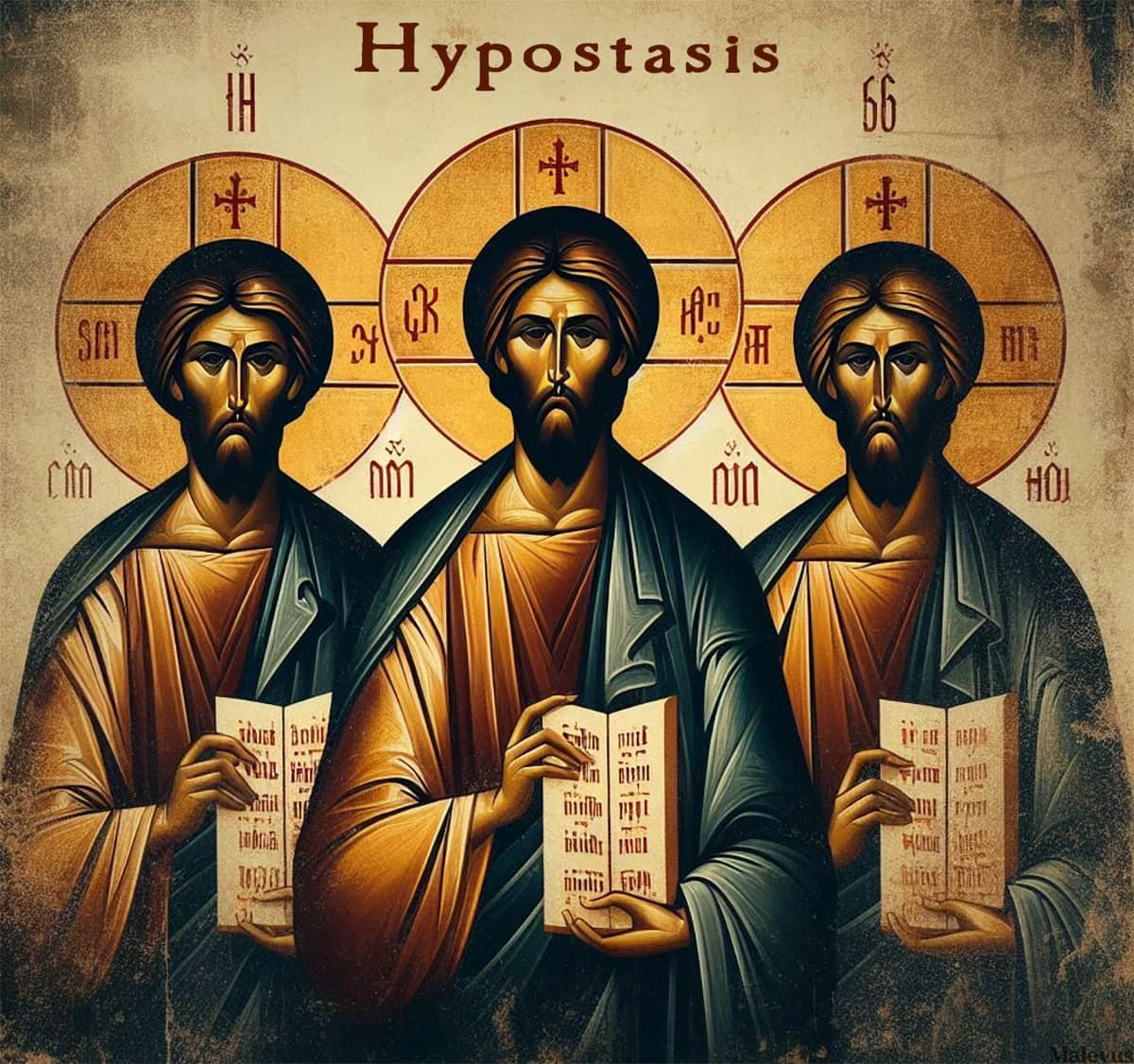

The term “Hypostasis” (Ancient Greek: ὑπόστασις) is used in Christian theology, predominantly in the Eastern tradition, to denote one of the three persons of the triune God: the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. The Greek word “ὑπό-стασις” literally means “underlying” and is translated into Latin as “substantia.” The term was widely used in the philosophical teachings of Plotinus, albeit with a different meaning, signifying a certain essence (or its part) rather than personality. One of Plotinus’s treatises is titled “On the Three Original Hypostases” (in Neoplatonism, these are the One, Intellect, and Soul).

Background

The meaning of the term “hypostasis” evolved over time and differs in various doctrinal Christian formulas, such as the Nicene Creed, the Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed, and the Chalcedonian Creed. The application of the concept of hypostasis in Christian theology can be traced back to the 4th century. Before the Cappadocian Fathers, the terms “hypostasis” (Ancient Greek: ὑπόστασις) and “essence” (Ancient Greek: οὐσία) were used interchangeably in Christian theological language (including the Nicene Creed and later in the works of Athanasius the Great) as synonyms, both denoting something that has independent existence, existing not in something else but “in itself.”

A hypostasis is an essence, and it means nothing else than the very being. … For hypostasis and essence are existence.

online pharmacy order buspar online with best prices today in the USAbuy fluoxetine online http://francisholisticmedicalcenter.com/resources/html/fluoxetine.html no prescription pharmacy

God exists and has existence. Athanasius the Great

Plotinus first applied the term “three hypostases” to the Divinity, defining the mutual relationship of the One, the Intellect, and the Soul. He attempted to draw, albeit unclear, distinctions between the Ancient Greek terms οὐσία (ousia) – essence, meaning “being,” and ὑπόστασις (hypostasis), meaning “hypostasis” or “how (whose) being.” The credit for precisely defining both of these terms separately goes to Porphyry. According to Porphyry’s thought, God is one, but His essence is somehow expressed in three hypostases: in God as the highest good and source of all being, in the Intellect as the architect of the world, and in the Soul animating and sanctifying everything.

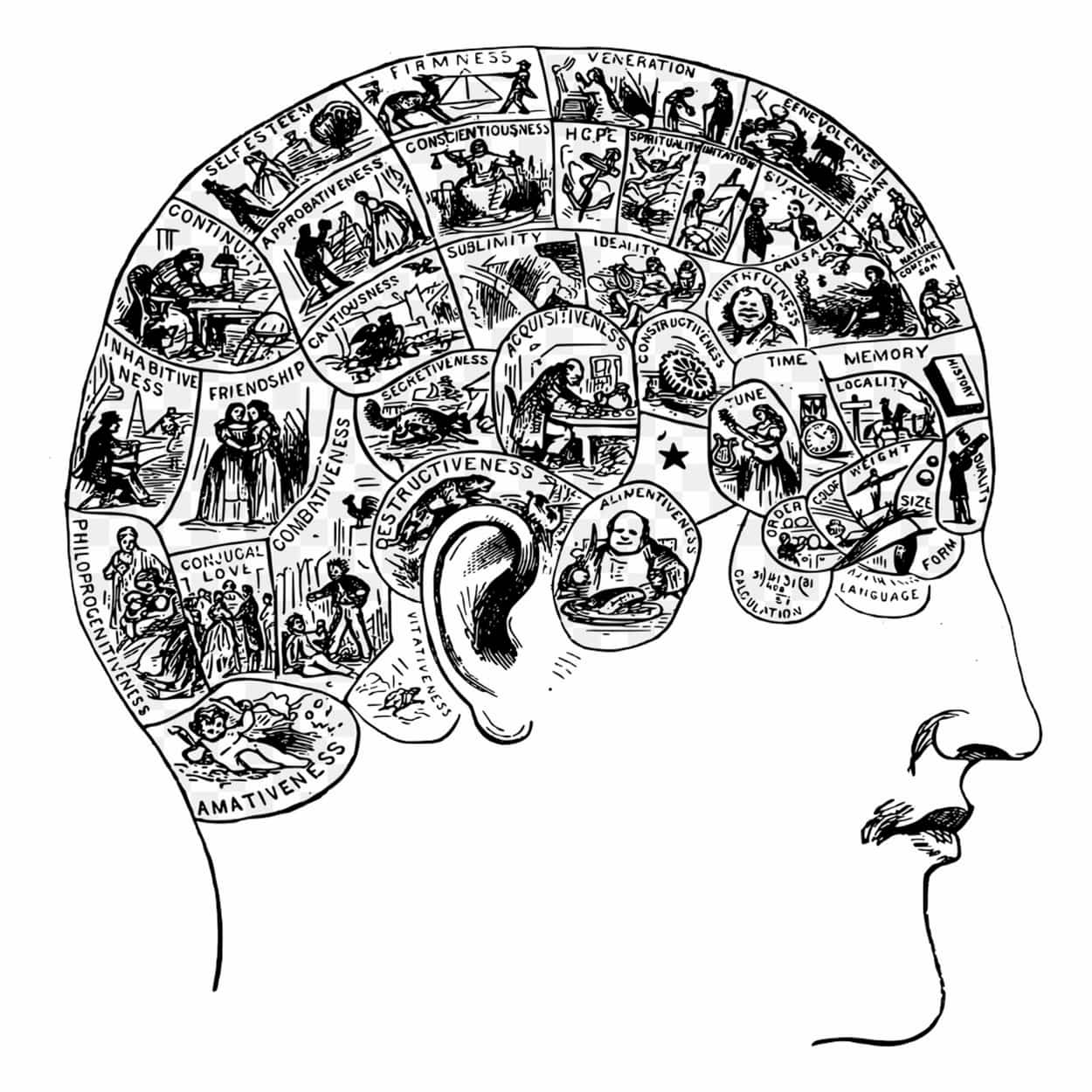

“Essence” is the first of Aristotle’s ten categories. Aristotle distinguished between primary and secondary substances. Primary substances (Latin: substantia concreta, concrete substance) are specific individuals, like a particular person or a specific horse. Secondary substances (Latin: substantia abstracta, abstract substance) are general concepts, like horses in general or humans in general.

Teaching of the Cappadocian Fathers

Basil the Great explained the difference between essence and hypostasis as being between the common (Ancient Greek: κοινὸν) and the particular (Ancient Greek: ἲειον). This made it clear in Christian theology, especially in Triadology (study of the Trinity), that the word “essence” only refers to what Aristotle called secondary essences, or general ideas. Therefore, in patristics, the term “essence” ceased to require clarification; when mentioned without any qualifications, it refers only to the second essence. Thus, the concept of “essence” in Christian theology remains Aristotelian.

Basil the Great and Gregory of Nazianzus replaced the concept of “primary substance” with the term “hypostasis.” Still, they did so in a way that extends the meaning of the Christian term far beyond the boundaries of the Aristotelian definition of primary substance. When Basil the Great defined hypostasis through Aristotle’s definition of primary substance, he was, in reality, not so much defining this concept as determining its place in the new system of categories:

“Both essence and hypostasis have the same difference between them as between the common and the particular, for example, between a living being and a particular man.” — “Epistle 236 (228), to Amphilochius of Iconium, the Bishop of Iconium”

This definition indicates that, in the new categorical apparatus, one of Aristotle’s ten categories (more precisely, one of its two varieties: primary substance) is replaced by a new category – hypostasis. In other words, a new category, the eleventh, is introduced instead of Aristotle’s “primary substance.

“

At the same time, as Basil the Great explains in the same context, this definition of hypostasis is necessary because defining the Father, the Son, and the Spirit simply as “persons” is insufficient. For Basil the Great, as well as for other Cappadocian Fathers, the term “person” (Ancient Greek: πρόσωπον) traditionally used in Christian theology concerning the Trinity seemed inadequate, as it gave rise to heretical interpretations like that of Sabellius (for whom the three “persons” were akin to “masks”).

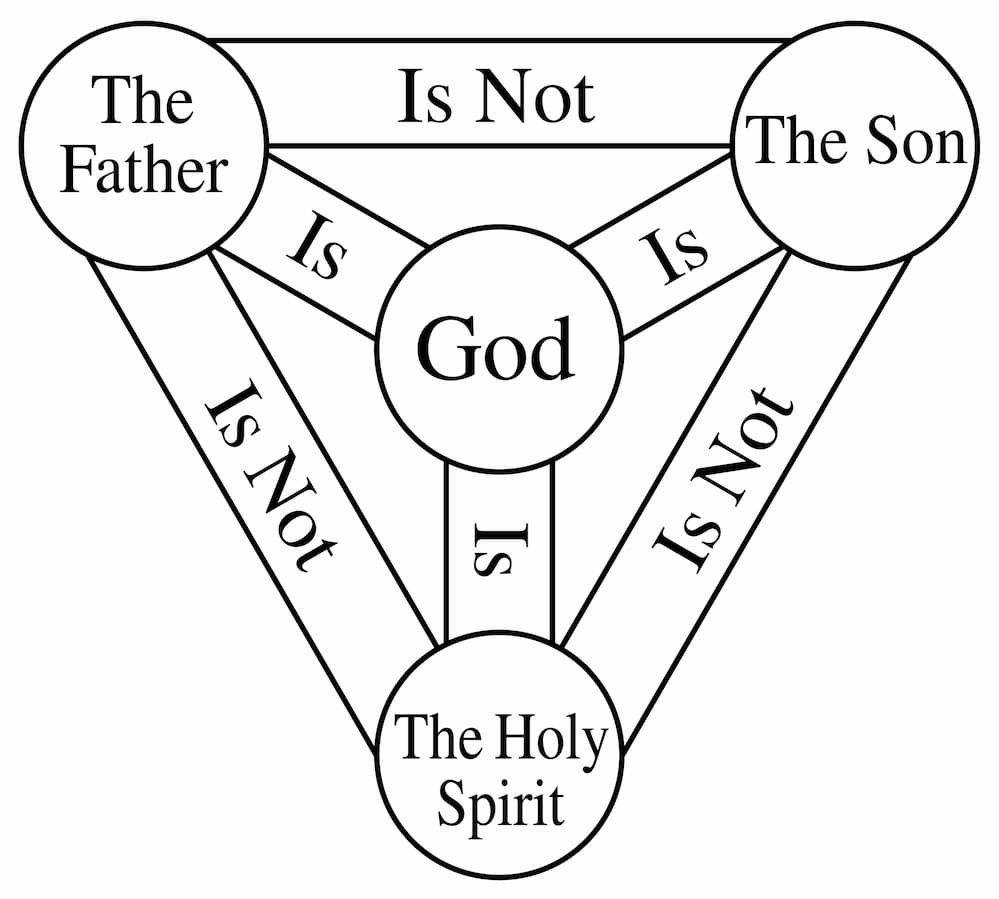

However, by defining the “persons” of the divinity as “hypostases,” any pretext to consider these persons as some kind of mask on the same reality is removed. The term “hypostasis” unequivocally indicates that there are three realities. Basil the Great provides a detailed explanation of the concept of “hypostasis,” primarily in his work “Against Eunomius.” However, opponents of the Cappadocians from the Nicene party accused them of tritheism since they understood the three hypostases as three distinct entities.

Gregory of Nazianzus, in Oration 31, “On the Holy Spirit,” refers to the three hypostases of divinity as τα εν οις θεοτης (“that in which divinity is,” or more literally, “those in which divinity is”), thus defining hypostases as a kind of “reservoirs” of the essence. In the same spirit, Gregory of Nazianzus expresses himself in the Dogmatic Poems, 20, “On the Holy Spirit,” stating that the three hypostases “possess divinity” (i.e., essence).

Why was there a need to seek special definitions for hypostasis, and why couldn’t they suffice with Aristotle’s definition of primary substance? Aristotle’s primary substances were inadequate for expressing the Trinity of divinity.

According to the thoughts of 4th-century Christian theologians, the unity of the three hypostases of the Trinity—though not to the extent that the three hypostases lose the autonomy of their existence (contrary to the Modalists), nor to the extent that they are as distinct as, for example, three horses or three individuals.

It was necessary to express the unique ability of the hypostases to be mutually united, as in the Son being in the Father and the Father in the Son. It was also necessary to express the ability of the hypostasis of the Son to incorporate humanity. Therefore, both in describing intra-Trinitarian relations and in describing the incarnation of the Logos, the concept of hypostasis had to be confronted as a vessel of the essence, not just as a “part” of the whole.

In conclusion, hypostasis is a particular entity that, at the same time, serves as the “vessel” of the common essence.

A pivotal event in the history of trinitarian disputes within the Christian Church was the Council of Alexandria in 362 AD, where two factions were present: the “old Nicenes” (Alexandrians) and the “new Nicenes” (Antiochenes). The former held the view that the Triune God is one essence or one hypostasis, while the latter, using new terminology, taught about God as one essence in three hypostases.

Later, under the influence of Cappadocian theology, the teaching of the “new Nicenes” prevailed in Greek trinitarian theology. In Latin, the Nicene idea that essence (essentia) and hypostasis (substantia) were the same thing stayed true. This is why Roman Catholics still believe in the Trinity as one essence-hypostasis in three persons (personae), as they confessed, with the phrase “unius substantiæ cum Patre,” which means “of one substance with the Father.”

Modes of Existence

In the treatise “Against Eunomius,” Basil the Great defines the three hypostases of God as three distinct “modes of existence” (Ancient Greek: τρόποι ὑπάρξεως). The Greek word “tropos” is accurately rendered into Russian as “image” in the sense of “manner” or “way.” The word “existence” (Ancient Greek: ὕπαρξις) in this context becomes a term signifying not just “being” (for which there were other synonyms) but the being of an individual.

Thus, the expression “mode of existence” can only relate to an individual, particular being, not the being of essence (nature), and therefore implicitly contains an “Aristotelian” definition of hypostasis.

The “mode of existence,” as understood by Basil the Great (and other fathers following him), is contrasted with the “logos of nature” (Ancient Greek: λόγος τῆς φύσεως), which is unknowable. For Basil the Great, any hypostatic existence, whether it is the three-hypostatic God (as in “Against Eunomius”) or the one-hypostatic human (for example, in “Letter 236”), is said to be knowable by the mode of existence but unknowable by the logos of nature. The latter should be understood in the sense that the “logos”—here used in the sense of “knowledge, understanding, concept”—of nature (essence) surpasses our understanding. To separately speak of the unknowable “logos” of nature makes sense when one has to talk about its knowable “modes” (images) of existence.

The word “existence,” both in Russian and Greek, is a nominalization of the action, and this holds crucial significance for choosing precisely this term in relation to hypostasis. The term indicates that the very existence of hypostasis should be regarded as an action, that is, as energy.

The “existence” (“mode of existence”) of the Father presents God to Christians as “paternity” (Ancient Greek: πατρότης), the Son as “sonship” (Ancient Greek: υἱότης), and the Holy Spirit as “holiness” (or “sanctification”: Ancient Greek: ἁγιασμός), corresponding to the “characters” or distinctive features (idioms) of each. Additionally, note that St. Basil casually applies the word “character,” usually denoting a person’s external appearance, to the hypostases of the Holy Trinity.

In later theological tradition (starting with Gregory of Nazianzus), a somewhat different nomenclature is “standardized” for the distinctive properties of the three hypostases of the Holy Trinity (“unbegottenness,” “begottenness,” “procession”). Nevertheless, in any case, it is only about some property that distinguishes each of the three divine hypostases from the other two. Since any naming of these properties is just one of the possible names of God, the primary significance of these designations is not to coincide with each other: each of the three hypostases has its distinctive hypostatic property, which should be named uniquely, while the actual name may vary.

However, the modes of existence of the three hypostases exist not only to the extent that we can know them but primarily in themselves. The essence is “existent” in each of the three modes of existence. “Existence” is the energy of the essence, its kind of movement. This is, in a sense, the movement of the Son and the Spirit in relation to the Father as the singular “principle” and “cause” in the Holy Trinity.

Liturgy

Concerning Jesus Christ, the Eastern Orthodox Church chants that He is “of one essence, but not of one hypostasis” (Ancient Greek: διπλούς την φύσιν αλλ’ου την υπόστασιν).

Personalism

There is a theory that the concept of hypostasis, developed in Trinitarian theology, led to the emergence of the notion of human personality in Greek and later European culture. Since humans are created in the image and likeness of God, the concept of the depth and uniqueness of personality—hypostasis—is transferred to anthropology as the perfect peculiarity and uniqueness of each individual. Before that, in ancient culture, an individual was considered an individual or, at best, a persona.