The shift from an agricultural-based economy to one based on automated, mass production of manufactured products began around the close of the 18th century with the advent of the industrial revolution. Innovations in technology and the availability of alternative energies aided this process. The phenomenon of the industrial revolution happens at various periods in each nation, marking the beginning of a significant social mutation and the emergence of a working class. Unlike England, Germany, and the United States, France’s industrial development in the 19th century was steady and significant rather than spectacular and marked by a period of abrupt acceleration.

England: the pioneer

Beginning in late 18th-century Britain, the first industrial revolution spread around the world. Both the British economy and social structure were drastically altered. The most noticeable changes occurred in production’s basic characteristics, as well as its mode and location. The primary product sector lost workers to the manufactured goods and services sectors. The creation of more sophisticated and productive machinery, like James Watt’s steam engine, greatly boosted the output of produced goods.

The systematic incorporation of both theoretical and empirical understanding of the manufacturing process also contributed to the productivity increase. Finally, it was found that concentrations of businesses in small areas were more productive. Thus, rural-to-urban migration and transnational movement from rural to urban places were connected to the industrial revolution.

Some of the most noticeable shifts occurred with regard to how labor is structured. The organization grew and added new capabilities. Production was now handled by the business itself, rather than by individual members of the family or within the context of a lord’s realm. Regularity and specialization increased as the workload increased. The utilization of capital increased dramatically in industrial output. Workers were able to crank out far more products because of the advent of cutting equipment and mechanized assembly lines. This tendency toward specialization was bolstered by the benefits of expertise in a certain activity (the production of a specific component or instrument).

Additional divisions between social classes emerged as a result of the industrial revolution’s increased reliance on specialized labor and massive investments in capital. A large industrial and possessing bourgeoisie, owner of the means of production, whose members became known as “capitalists,” and a class of workers, concentrated in manufacturing and heavy industries, who quickly formed a very homogeneous social class, brought the “social question” to the forefront of political debate at the end of the 19th century.

Prosperous growth in the economy

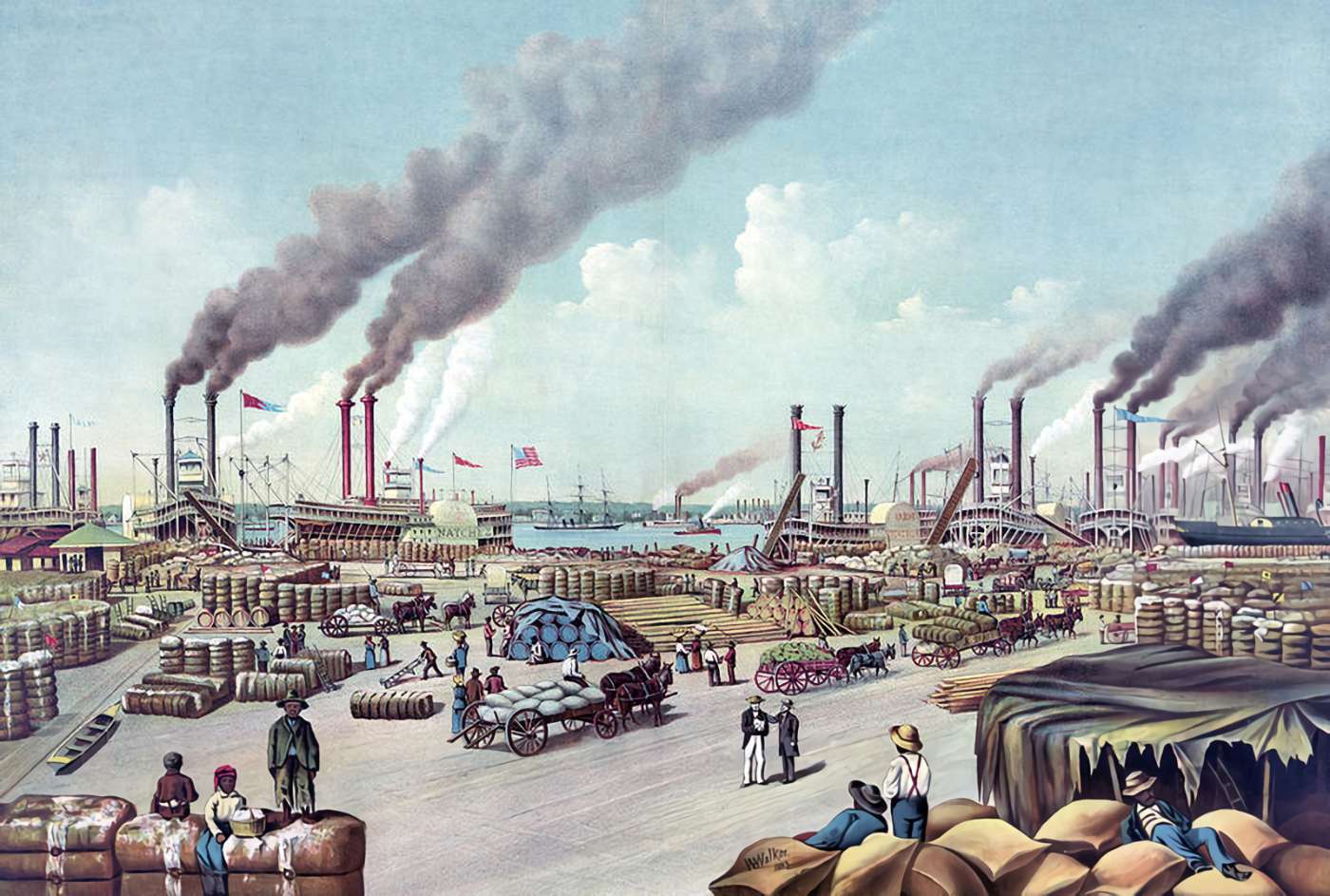

Britain was the experimental ground for a major economic and social shift since it was where the first industrial revolution took place. London was the hub of a global commercial network that facilitated the growing export of industrialization-era commodities for the majority of the 18th and 19th centuries. Exports, which capitalized on the British Empire’s reach, were crucial for supporting the booming textile and industrial sectors that had been propelled by technological advances.

Exports from Britain grew rapidly after 1780, according to available statistics, and the economy did well overall. Increasing exports and access to global markets benefited the economy in two ways: first, manufacturers were able to afford the low-cost raw materials (obtained from the colonies) they needed to launch their industries, and second, export merchants gained knowledge that was instrumental in fostering the growth of domestic trade.

The “economic take-off,” as described by economist W.W. Rostow, occurred when industrialization progressed slowly over Europe. This period, characterized by a surge in GDP, household consumption, savings capabilities, and investment, did not unfold simultaneously in all locations.

Between 1780 and 1820 in England, between 1830 and 1870 in France, and between 1850 and 1880 in Germany, the population “took off,” which had been preceded by high population expansion (owing to reduced mortality). Sweden and Japan experienced it at the very end of the 19th century, Russia and Canada in the early twentieth century, Latin America and Asia in the 1950s, and several regions of Africa and the Middle East decades later.

The Industrial Revolution in France

In this regard, France was in an unusual situation. From 1815 to 1860, France grew steadily but never had a true “take-off” in the 19th century. Historically, agriculture has played a larger role in the French economy than in other nations, which helps to explain why France is so far ahead of the rest of the pack. Iron output in France was obviously larger than in all of the German states combined by 1860, as the significance of industry in the growth of the industrial revolution increased from 1830 onwards.

The growth of the French railroad network from 3,000 km in 1850 to 17,500 km in 1870 and 50,000 km in 1913 was indicative of the country’s increasing industrialization. The expansion of related sectors like textiles, mining, and steel is further proof; the latter two were greatly benefited from the advent of these transportation innovations, as they have been able to bring in new sources of energy, rails, wagons, etc. Thus, the French “performance” is not inconsequential, albeit it lagged behind England’s throughout the first two-thirds of the century and the United States’ and Germany’s for the final third.

The role of the other countries in the Industrial Revolution

Both France and Germany faced competition from Britain as they launched industrialization, and the two countries reaped unequal benefits from the latter’s expertise. Free trade agreements between France and Britain were signed in 1860, which coincided with the slowing of the first industrial revolution in France. Due to inadequate industrialization, the French economy suffered as a result of this liberalization of trade (imports tripled, and industrial exports weakened).

Instead, the cards were reshuffled at this time, with Germany benefiting more than England as the latter country lagged behind the fast industrialization that was taking place over the Rhine (creation of large businesses, etc.). The Mediterranean region of Europe, on the other hand, was largely left out of the industrial revolution until the 20th century.

Although the British government had a significant role in fostering industrialization, it played an even larger role in Germany, Japan, Russia, and almost all other 20th-century industrializers. From this point on, the French government also started to meddle more obviously in the economy.

The consequences of the Industrial Revolution

Heavy industry and emerging industrial sectors, like the car industry, wreaked havoc on the economies of Europe and North America. Modern techniques of manufacturing and administration were developed by manufacturers so that the economy could continue to function normally. Fordism and Taylorism were management philosophies that emerged at the turn of the 20th century. Trusts, cartels, and an increase in the number of stockholders all contributed to a new look for the economy.

Increases in national income per capita, GNP, and GDP are the hallmarks of successful industrialization (GDP). It alters not just how resources are divided but also how people live, work, and interact with one another. Workers’ buying power and living circumstances declined during the outset of the industrial revolution in Britain, as they did everywhere, but ultimately improved as a consequence of general enrichment and workers’ fights.

The rise of trade unionism and Marxist socialist ideas at the century’s end led to these developments. However, the industrial revolution’s successful social group was the bourgeoisie, which tended to homogenize its way of life across the board, from the upper and lower classes that dominated finance and industry to the middle class that remained the norm despite its diversity.

The Industrial Revolution in a nutshell

The advent of the new industrial age usually represents a watershed moment in human development. The effects initially appeared in England. The Industrial Revolution catapulted the nation to the position of leading economic power on the basis of new sources of energy (coal), new materials (iron, steel), and advances (textiles, steam engines). However, a worldwide economic slump hit with the Vienna stock exchange crash of 1873.

The second industrial revolution, powered by electricity, oil, and chemicals, did not take form until 1896. The Great Depression of 1929 put an end to the new economy it had helped shape. To all appearances, the 20th century saw a third revolution, one that was mostly driven by technological advancements in areas such as computing, transportation, energy production, and, most notably, communication. But experts believe that it’s too early to judge it at this point.

TIMELINE OF INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION

A steam engine is constructed by Thomas Newcomen in 1705

The first commercially viable steam engine was created by the British inventor Thomas Newcomen and the engineer Thomas Savery. Steam engines were already in use for pumping water by the time Thomas Savery developed his in the years before. In this way, the collaboration between the two individuals made it possible to upgrade this apparatus with an atmospheric engine (also known as a “fire pump”). In 1712, Newcomen first put it to use in a mine to power water pumps. However, engineer James Watt made significant advancements in its practicality and efficiency in subsequent years.

Coke was first used in metalworking in 1709

An Englishman named Abraham Darby used coke to process iron ore in the town of Coalbrookdale. Coal was distilled into coke in an old process. Coal had been used as an energy source for smelting in certain European nations for many years, leading to widespread forest loss. This prompted the need for research into other combustion techniques. Darby’s acquired iron didn’t seem to be of high quality. But he and his family were able to refine the method throughout the next decades.

John Kay perfected the weaving process in 1733

The “flying shuttle,” invented by the Britishman John Kay, greatly increased the weaving pace. With the help of this innovative mechanical technology, weavers could create considerably larger textiles at a much faster rate. So, fewer people were needed to get the job done. However, weavers soon ran out of raw materials as yarn manufacturing yield declined. As a result, numerous scientists and technologists worked to enhance the spinning process.

Hargreaves created the first spinning machine in 1767

James Hargreaves, a weaver from Britain, developed the “spinning jenny,” a device that spun eight threads at once with only one spin of the handle. After Hargreaves submitted his patent application in 1770, weavers began using more threads in their creations. But since it needed human involvement, this method was not used by businesses.

In 1769, Richard Arkwright created the first mechanical weaving machine

After seeing Hargreaves’ weaving machine, Richard Arkwright was inspired to invent his own version, the “water-frame,” which was driven by a hydraulic loom. He officially marks the introduction of the first mechanized loom with this signature. The need to hire industrial workers to operate the looms meant the end of home weaving as well. Early in the 1770s, Arkwright established a manufacturing facility of his own.

James Watt refined the steam engine in 1769

Scotsman James Watt patented the modifications he made to Newcomen and Savery’s steam engine, including a chamber to concentrate the steam and provide more energy, a double-acting mechanism in which the steam itself powered the piston, a flywheel, and a ball regulator to change the machine’s working speed.

All the way until the 1780s, James Watt was making improvements. In the end, he and Matthew Boulton were able to mass-produce their machine after years of trial and error. Other engineers stepped in to refine the system even more after 1800. Since the steam engine was effective and could generate a great deal of power, it found widespread application in manufacturing.

In 1779, weaver Samuel Crompton perfected his invention

The work of Hargreaves and Arkwright influenced Samuel Crompton to create the “mule-jenny.” This mechanized loom was capable of producing a large quantity of yarn suitable for any kind of thread. The weavers were unable to keep up with the increased output, and an excess of raw materials resulted.

Henri Cort created puddling on February 13, 1784

The method of puddling was created by the British scientist Henri Cort. For higher-quality iron or steel, this allowed for the refining of cast iron by lowering its carbon content. The cast iron was heated to extreme temperatures in a furnace while being agitated with a hook and oxidizing slag. During the time period known as the British Industrial Revolution, this discovery was among the most significant breakthroughs in the field of metallurgy.

Cartwright created the first practical mechanical loom in 1785

The first mechanized loom was created by a British man named Edmund Cartwright. Since Crompton’s weaving machine was developed, the quantity of yarn produced has much surpassed that of the weavers. Harmonizing raw material manufacturing with weaving was made possible by Cartwright’s approach.

1801: The British Parliament enacts the Enclosure Act

Enclosure in farming became the law of the land in Great Britain. All farmland must be secured and private from that point forward. Since the Middle Ages, people have used fences to separate different plots of land in what is known as the “enclosure system.” This kind of system first took shape in the 15th century.

Large landowners drove the peasants off the community fields and pastures, ending communal farming in favor of more individualized methods of production. Damaged, the exiles had little choice but to seek employment in other industries. After 1760, the system began to see rapid growth and spread over the nation. Commercial farming was made possible by enclosure, which sparked a movement known as the “agricultural revolution” in Britain.

February 21, 1804: First test of a steam locomotive

In England, Richard Trevithick fired up the first steam locomotive, which attained a top speed of 8 kilometers per hour. When twenty years passed, passenger service was finally introduced. Nonetheless, the most important factor in England’s industrial revolution would be the quick transfer of vast amounts of resources across various economic zones.

September 28, 1825: First passenger transport by train

George Stephenson, an English mechanic and the genuine creator of the locomotive, created the first public railway line. The purpose of this connection between Stockton and Darlington was purely economic. The first railroad track was built in England. George Stephenson created the “Rocket,” a locomotive that would set speed records, in 1829.

Beginning on August 27, 1859, oil was produced in Pennsylvania

In Titusville, Pennsylvania, U.S. military officer Colonel Edwin Drake constructed the first derrick (drilling tower). When the well was 23 meters deep, the priceless liquid began to stream out. Oil lamps had traditionally utilized this oil as fuel, but in more recent years, it had also been distilled into fuel. Black gold mania had broken out, and the finding of fresh resources led to the emergence of settlements in previously uninhabited areas of the desert.

Mendeleev unveiled his periodic table of elements on March 6, 1869

When Dimitri Ivanovitch Mendeleev presented his “periodic table of elements” to the Russian Chemical Society, he made history in the field. By organizing the 63 known chemical elements, he found that certain chemical characteristics of those elements tend to occur in clusters at predictable intervals. As a result, in his table, similar characteristics could be seen among the elements in adjacent columns. The discovery of new elements naturally found its place on Mendeleev’s table after his innovation shook up the chemical industry.

9 May 1873: Crash of the Vienna stock exchange

In Vienna, Austria, the stock market crashed. As soon as the crash began, it had an impact on Germany and subsequently on the United States. To be more precise, it marked the beginning of a period of economic stagnation or perhaps catastrophe that would endure until 1896. Eventually, the oil, power, and chemical sectors helped Europe and North America regain economic development. The term “second industrial revolution” has been used to describe this time period.

Incandescent lamp was invented by Thomas Edison on October 21, 1879

Thomas Alva Edison created the incandescent light bulb at his Melo Park, New Jersey, laboratory. He utilized Japanese bamboo to make the filament for a vacuum-powered light bulb. The burnt bamboo, which was connected to two platinum wires, immediately started emitting electric light. The young American inventor at the time was just 29 years old. On January 1, 1880, he revealed his invention to the American public, and they were blown away.

The first automotive patent was filed by Carl Benz on January 29, 1886

The first vehicle was created by Carl Benz, who put an internal combustion engine inside a tricycle and added a transmission and a differential. Although other motorized devices, such as Joseph Cugnot’s steam-powered fardier, did exist, it wasn’t until Carl Benz’s tricycle that a car was finally developed to the point that it could be mass-produced and sold to the public. Many different makes and types of cars emerged as a result of the rapid evolution of the vehicle. Carl Benz, meanwhile, would become the CEO of a successful business that, after many name changes and mergers, is still going strong today as DaimlerChrysler or Daimler AG.

1911: Taylor published “The Principles of Scientific Management”

The German-American engineer Frederick Winslow Taylor wrote a book outlining the principles of his workplace management method. Later dubbed “Taylorism,” this method sought to increase workers’ efficiency by instituting a more methodical approach to scheduling and assigning tasks. Following much research and deliberation inside the Midvale Steel Corporation, he originally pushed for the division of labor.

Managers planned and scheduled everything, while employees could only do what their duties required. Although the new approach was successful, it was not well received by the workforce, which complained that they had been reduced to mindless automatons.

January 14th, 1914: The beginning of an era called “Fordism”

Henry Ford, an American automobile maker, introduced the assembly line, a revolutionary way of organizing production line labor. The amount of time needed to build a Ford “T” was drastically cut due to this development. Factory output quadrupled from 6 hours to 1 hour and 30 minutes. Now forth, the worker put together whichever components come into view. “Fordism” is a widely-used manufacturing concept now.

The stock market crashed on Thursday, October 24, 1929

The New York Stock Exchange went bankrupt on this day. Twelve million shares were traded in only a few short hours. In response to the decline in prices, speculators rushed to unload their holdings. All of our prices were reduced by 30%. On Tuesday, October 29th, confirmation of the “crash” was made public. The “crisis of 1929,” which began on “Black Thursday,” is the worst economic disaster in history. As a result, the political and economic stability of the whole globe was threatened, and the United States was effectively annihilated.