The Jacquerie, which took place in May and June 1358, was a revolt of peasants from the rural areas of Île-de-France, Picardy, Champagne, Artois, and Normandy during the Hundred Years’ War. It occurred in the context of a crisis in the Kingdom of France: King John II of France (John the Good) was in captivity in England and the dauphin Charles faced opposition from two powerful figures: King Charles II of Navarre (Charles the Bad), a claimant to the French throne, and the provost of the merchants of Paris, Étienne Marcel.

The reasons were numerous, including the unpopularity of the nobility following the defeat at Poitiers (Battle of Poitiers), Étienne Marcel’s revolt in Paris in February 1358, and unrest in the cities of the County of Flanders.

This revolt was short-lived, erupting at the end of May 1358, possibly on the 23rd or 28th, on the border between Île-de-France and Clermontois, particularly in a small village called Saint-Leu-d’Esserent. The main group of rebels was crushed on the 9th and 10th in Picardy, near Mello (the current department of Oise), by an army of nobles assembled by Charles II of Navarre.

—>The jacquerie coincided in time with the Paris revolt of 1358, led by the bourgeois provost of Paris, Étienne Marcel.

What Does Jacquerie Mean?

This revolt derives its name from Jacques Bonhomme, the archetype of the “peasant” or “commoner,” and later a nickname for French peasants in general, likely because they wore short jackets referred to as “jacques.” It was led by an individual named Guillaume Carle, also known as Jacques Bonhomme.

This revolt is the origin of the term “jacquerie,” later used to refer to various popular uprisings by the chronicler Nicole Gilles (died in 1503) in “Les chroniques et annales de la France,” published as early as 1492.

Background of Jacquerie

This rebellion occurred during a challenging period marked by the Hundred Years’ War, which commenced in 1337, and the Black Death epidemic in 1348.

France experienced several defeats, notably at Crécy in 1346, during the reign of Philippe VI, and at Poitiers in September 1356, under the rule of Jean le Bon, who became a captive of the English first in Bordeaux (the capital of the Duchy of Guyenne, a French fief held by the King of England), and later in London (April 1357).

These defeats brought discredit to the French nobility, steeped in chivalry but incapable of overcoming a less chivalrous yet more efficient English army.

The authority wielded in the absence of the king by Dauphin Charles (1338–1388) was contested. Charles II, King of Navarre (1332-1387) and grandson of Louis X of France through his mother, Jeanne de Navarre, considered himself deprived of the French crown due to the decision in 1328 to exclude royal princesses from the succession. In Paris, Étienne Marcel, the provost of the merchants, aimed to establish a certain level of control over the monarchy within the framework of the Estates-General.

In March 1357, a one-year truce was agreed upon. However, this resulted in demobilized mercenary companies, known as the “great companies,” plundering villages and extorting cities without pay.

Charles II of Navarre, incarcerated by John II of France in April 1356, was released by the dauphin in 1357, allowing him to resume his intrigues successfully.

This situation compelled John II of France to negotiate a rather unfavorable treaty with Edward III in January 1358, leading to the open rebellion of Étienne Marcel in February 1358. Paris fell under the control of the provost of merchants, and the dauphin placed the city under siege.

Economic and Social Problems in Town and Country

There are numerous opinions on the causes of this uprising, and although it was triggered by specific circumstances, it can be linked to a series of French medieval peasant revolts and disturbances. This rebellion can also be compared to the English Peasants’ Revolt of Wat Tyler in 1381, the Tuchins’ revolt in Normandy and southern provinces (1356–1384), the Maillotins’ uprising in Paris in 1382, and the Taborite movement (Hussite movement) in Bohemia. To some extent, the 1358 uprising served as a connecting link between medieval peasant revolts and the religious movements of the early modern period.

Historians debate the class character of the Jacquerie, and while acknowledging the presence of nobles among the rebels, they cast doubt on the homogeneity of the movement. In addition to the refusal to pay taxes, the Jacquerie was motivated by the peasants’ desire to defend their dignity. The Jacquerie significantly influenced public consciousness, and henceforth, peasant disturbances were referred to as “Jacquerie” as a generic term.

The reasons for the uprisings may include:

- The Hundred Years’ War, led to increased taxes.

- Famine and diseases in Europe, worsened the already difficult situation of peasants.

- Intensified exploitation of peasants, changes in the economy (trade), and feudal lords, desiring to buy expensive goods from other countries, began demanding monetary dues.

According to the renowned French historian of the Annales School, Georges Duby, the motivating factor for the rebels was military violence: “The Jacquerie was neither a revolt of the poor nor a rebellion against the king. This uprising was an explosion of rage from prosperous peasants of Beauvais, who could no longer bear the exactions of military service. One fine day, gathering in Saint-Leu-d’Esserent, they unleashed their anger, descending on these people as villagers everywhere descended on bandits.”

Guillaume Cale

Guillaume Cale, one of the peasant leaders of the uprising, sought a strong ally in the form of urban dwellers for the scattered and poorly armed peasants. He attempted to establish connections with Étienne Marcel and sent a delegation to Paris, seeking assistance for the peasants in their struggle against the feudal lords. Simultaneously, he headed to Compiègne. However, wealthy urban dwellers prevented the rebellious peasants from entering.

The same occurred in Senlis and Amiens. Étienne Marcel established communication with peasant forces and sent a Parisian unit to help them dismantle fortifications erected by the feudal lords between the Seine and the Oise rivers, hindering the supply of provisions to Paris. However, this unit was later recalled.

By that time, the lords had recovered from their fear and began to act. Against the rebels, both Charles the Bad and the Dauphin Charles mobilized simultaneously.

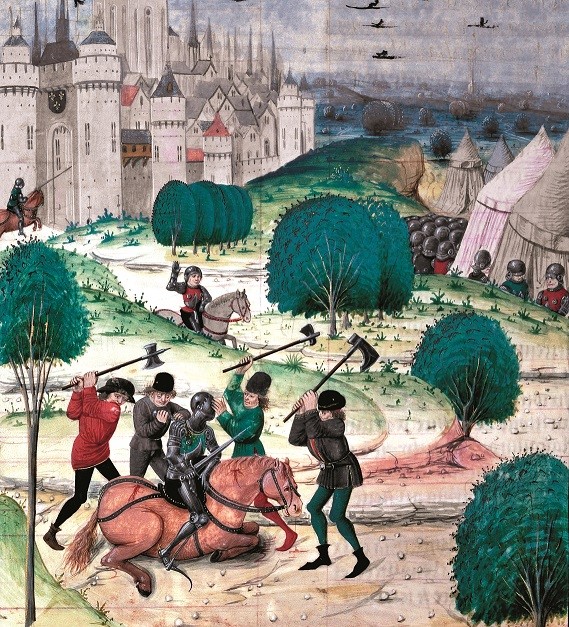

On June 9, 1358, with a well-trained army of a thousand men, Charles the Bad approached the village of Mello, where the main forces of the rebels were located. Despite significant numerical superiority, the untrained peasants had virtually no chance of winning in open combat. Guillaume Cale suggested retreating to Paris, recognizing the odds. However, the peasants refused to heed their leader’s counsel, insisting that they were strong enough to fight. Cale strategically positioned his forces on a hill, divided them into two parts, and constructed a barricade with carts and debris in front, placing archers and crossbowmen. He formed a separate cavalry unit.

The rebels’ positions appeared so formidable that Charles of Navarre hesitated for a week before deciding to attack. Eventually, he resorted to cunning and invited Cale for negotiations. Trusting his chivalrous words, Guillaume did not secure his safety with hostages.

He was immediately seized, chained, and demoralized, and the peasants were subsequently defeated. Meanwhile, the Dauphin’s knights attacked another group of Jacques, annihilating many rebels.

Repression of the Revolt

A massive crackdown on the rebels ensued. Guillaume Cale was executed after brutal torture (the executioner “crowned” him with a red-hot iron tripod on his head). By June 24, 1358, at least 20,000 people had been killed; the massacre only subsided after the amnesty declared on August 10 by the Dauphin Charles, although many feudal lords chose to overlook it.

Peasant unrest persisted until September 1358. Fearing popular revolt, the royal government hastily negotiated peace with the English.