Jean-Jacques Rousseau, as a young man, fled to Switzerland with his French Protestant family to escape religious persecution. He was born in Geneva on June 28, 1712. A few days after he was born, his mother passed away. His father, a watchmaker who was not very wealthy, gave him the best education he could but left the family in 1722. Jean-Jacques Rousseau was placed in the care of his uncle Bernard and sent to a boarding school in Bossey run by pastor Lambercier when he was ten years old. The years that he spent with his relatives in nature were the ones he remembered as most joyful. The next step was an apprenticeship under a very strict master engraver. Rousseau, at the age of 16, escaped from Geneva and began a life on the run.

- Discourse on the Arts and Sciences

- Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s books

- Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s social contract

- Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s condemnation and wandering

- Jean-Jacques Rousseau facing Voltaire

- Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s death and lasting impact

- Philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau

- TIMELINE OF JEAN-JACQUES ROUSSEAU

During the year 1731, Jean-Jacques Rousseau was introduced to Madame de Warens. In order to meet with the catechumen, the baroness sent him to Turin. Even though he had just converted to Catholicism, he still felt out of place in his new environment. The Confessions provided a not-so-pretty picture of the hospice’s environment. So, he ran away and joined Françoise-Louise de Warens at Les Charmettes, a little village close to Chambéry, where he resided until 1742.

Again, the Charmettes was significant because Rousseau recognized nature’s allure and praised it for pages. Louise de Warens assumed responsibility for educating the young man more formally. However, the nature of the connection between the two characters remained unclear. Even though she was 13 years older than Rousseau, the age difference didn’t stop the two from having an affair.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau moved to Paris in 1742 with the goal of becoming famous there as a musical genius. He had a rocky start, but eventually, he befriended Diderot. Both men learned that they were from the tiny bourgeoisie and that their lifestyles were quite modest.

It won’t be long until they are contributing to the Encyclopedia (“Encyclopédie”), with Rousseau heading up the music section. During this time, he also began to develop a friendship with Louise d’Épinay. Moreover, in 1745, he married Thérèse Levasseur, a linen servant. They planned to have five children and then relied on government aid since they wouldn’t afford to raise them. Although this was commonplace at the time, it would come back to haunt Rousseau in the form of vicious criticism.

Discourse on the Arts and Sciences

Diderot was imprisoned in 1749 because his works were considered subversive by the government. But it was while paying a friend a visit that Jean-Jacques Rousseau came upon the topic of the competition of the Academy of Dijon: “If the re-establishment of sciences and arts has aided to cleanse the morality.” For him, it was a true epiphany. After devoting his life to music up until that point, he found this philosophical topic fascinating and entered the contest.

In his reply, he elaborated on a conception of man as being naturally good but tainted by modernity. In July of 1750, Paul found out that his Discourse on the Arts and Sciences had earned him the award. Within that time frame, he gained notoriety among academics and the general public alike.

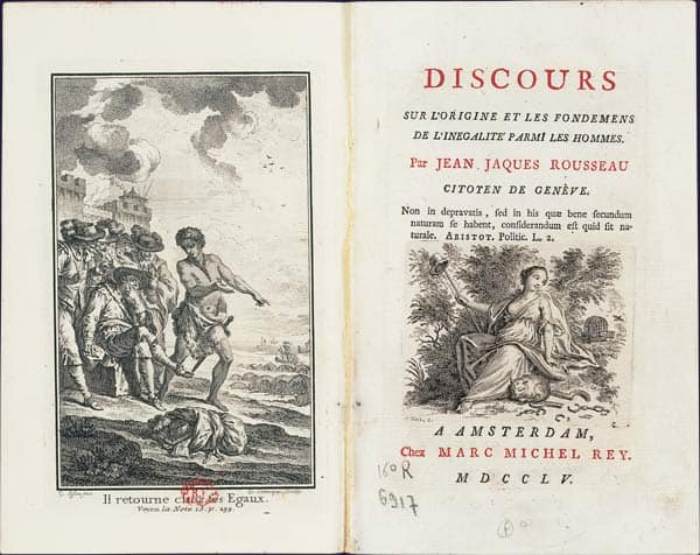

The “Second Discourse,” or “Discourse on the Origin and Basis of Inequality Among Men,” written by Jean-Jacques Rousseau five years after the first, elaborates on these ideas and provides more evidence for them. Every time something good happens, something bad also happens. His beliefs go counter to the widely held view at the time, which emphasized development at every turn. He bases his argument on a picture of man as he was in the Christian Garden of Eden, which is to say, in a state of nature, prior to the establishment of society and the beginning of history.

However, Rousseau fails to identify a concept analogous to original sin, and instead only suggests that man was compelled to join with his fellow men in order to build society. At that time, he was corrupted by a nefarious group. Contrast this with Hobbes, who believed that “man is a wolf to man,” in his own thesis.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s books

Thus, it was not the music in which Jean-Jacques Rousseau put his expectations but rather the revolutionary views that brought him to prominence. His opera, however, Le devin du village, was presented to the king in 1752 and was a smashing success. Rousseau’s participation in the “Querelle des Bouffons” didn’t help his musical career.

Instead, it is the book Julie; or, The New Heloise, in which the protagonists’ trip demonstrates the advantages of living in harmony with the laws of nature, that has been widely read and acclaimed. Clearly, we are not arguing for a return to savagery, but for a life guided by reason and morals.

With the publication of Emile, or On Education and the Social contract the following year, he provided more explanations of his ideas. His ideology rests on the twin pillars of freedom and equality. If Rousseau is to be believed, Rousseau believes that only equality can guarantee safety, and that no fair society can be founded through force. Moreover, in the The Profession of Faith of a Savoyard Vicar which accompanies the Social Contract, he defends a religion based on heart and reason and rejects writings and institutions.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s social contract

The political and social philosophy book “The Social Contract, or Principles of Political Law” was published in 1762. Jean-Jacques Rousseau advocates for ideas like popular sovereignty, individual liberties, and social equality. The book was promptly restricted after its publication in both Geneva and France. In this essay, he expands on his previous theses on man’s inherent freedom and social contract, and he seeks to find a middle ground between the two.

In a fair society, everyone has the right to vote and hold public office. Therefore, the contract must be a reflection of the popular will, and Rousseau is really advocating for some kind of participatory democracy. The ideas of Rousseau’s “Social Contract” formed the bedrock of contemporary politics, even if they were never implemented exactly as he described them.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s condemnation and wandering

Jean-Jacques Rousseau spent a year composing a scathing critique of the current educational system and the authoritarianism of instructors. Also, he cast doubt on the political system by saying that the cornerstones of a fair and happy society are freedom and equality. Finally, he railed against the Church by declaring that religion need not have it. Such writings, however, cannot be released without consequence. Paris’s parliament slammed them, and afterward, Geneva, the Netherlands, and Bern (the de facto capital of Switzerland) also banned them.

This meant that Rousseau would have to spend the rest of his life on the run from the law. Furthermore, near the end of the 1750s, he clashed with Diderot and Louise d’Épinay over his anti-theatrical ideas. After losing all of his backing, he fled to Switzerland but was met by a mandate instead. At long last, he arrived in Motiers, the capital of Frederick II‘s Prussia.

The ideal society that Rousseau proposed, however, also had its supporters. In fact, he was asked to assist in the constitution-writing processes in both Poland and Corsica. However, the big European powers would make it so that these two weaker governments almost never got a chance to put them into practice.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau facing Voltaire

Voltaire’s anonymous assault against Jean-Jacques Rousseau, titled “Le sentiment des citoyens” (The Sentiment of the Citizens) was published in 1764. The next year, the people of Motiers, influenced by the town pastor, pelted his home with rocks. Later, he ran away to a little island in Lake Bienne. Once again evading, he accepted David Hume, the philosopher, in England. The men quickly disagreed, however, and Rousseau went back to Europe.

Feelings of persecution soon began to consume Rousseau. His detractors did not hold back in their assaults on him, but he still thinks the whole human race is plotting against him. In The Confessions and Rousseau, Judge of Jean-Jacques, he tries to make his case and clear his name. He eventually leaves Paris for the little town of Ermenonville in Picardy, where he lives out the rest of his days in relative poverty and quiet. His primary interests shifted to botany and walking, and he even wrote an incomplete book on them called “Reveries of the Solitary Walker” (Les Rêveries du promeneur solitaire).

Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s death and lasting impact

On July 2, 1778, Jean-Jacques Rousseau passed away at Ermenonville. He died nine years before the Revolution, yet he left behind not just a new political theory but also The Confessions and the Reveries. So influential was The Social Contract to German idealism that Kant dubbed Rousseau the “Newton of the moral world.”

The revolutionary crowd admired his view of universal sovereignty as based on the common good rather than the sum of individual wills. By having his ashes placed in the Pantheon in 1798, Rousseau was elevated to national hero status. Beyond his political legacy, however, Rousseau also left a literary one; the lyricism and emphasis on nature and reflection in his later writings, particularly the Reveries, anticipate romanticism.

Philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau

“I would rather be a man of paradoxes than a man of prejudices,” Jean-Jacques Rousseau said in Emile. Many facets of his philosophy and life serve to highlight this principle, whether via his own actions or those of others. The Confessions provide a detailed account of a life lived in isolation and the fear of being persecuted. The work’s paradoxes are reflected in its structure: in his quest to explain “a man in all the reality of his nature,” Rousseau makes some concessions to his own view of man, who is good by nature but corrupted by civil society, religion, authority, and artifice.

However, it was inside this community that Rousseau found fame; he was honored by the Academy, and he made friends among the encyclopedists. But as swiftly as he had risen to prominence, Rousseau plummeted back down to earth when he realized that the Enlightenment’s progressive aspirations were at odds with his own adoration of nature. His detractors were quick to point out the obvious: a man who has abandoned his five children is hardly someone who should write a book on education. The Revolution, however, lionized him, and history would remember him as a major Enlightenment thinker. Even while his criticisms of representative democracy were usually polemical, he still remained an important point of reference for those who did.

TIMELINE OF JEAN-JACQUES ROUSSEAU

Jean-Jacques Rousseau was born in Geneva on June 28th, 1712

Jean-Jacques Rousseau came from a line of watchmakers in Geneva, where he was born. “I cost my mother her life, and my birth was the first of my misfortunes,” Rousseau says in the “Confessions” after his mother does not survive delivery and passes away a few days later.

In 1722, Rousseau’s father abandons the family

After leaving Geneva with Rousseau in the care of his brother-in-law, Rousseau’s father eventually abandons the family. Jean-Jacques stays with his uncle’s pastor, Lambercier, for boarding school. Rousseau remembers those times fondly.

March 1728: Rousseau flees Geneva

After a difficult apprenticeship with the dictatorial engraver Ducommun, Jean-Jacques Rousseau moves on from Geneva. The boy, being 16, goes to live with Madame de Warens in Sardinia. She converted him and sent him to Turin, since she was a contemporary Catholic.

In the year 1732, Staying at Charmettes

Jean-Jacques Rousseau moves in with Madame de Warens at Les Charmettes after spending some time at the seminary in Paris. He makes a living teaching music, a skill he honed in Annecy. After leaving in 1737, he came back in 1742.

Rousseau moves to Paris in 1743

As a result, Jean-Jacques Rousseau made his home there. He rapidly became friends with Diderot and Madame d’Epinay. He corresponded with his future adversary, Voltaire, and contributed to the encyclopedia.

His wedding to Thérèse Levasseur took place in 1745

Jean-Jacques Rousseau married the uneducated Thérèse Levasseur, a linen servant. It was very unusual for people of different social classes to be married without regard to social standing.

July 1752: Rousseau wins the competition at the Academy of Dijon

In his first major public address, “Discourse on the Arts and Sciences,” Jean-Jacques Rousseau explains how social stratification came to be. The prize catapulted him into the Parisian intellectual elite within the next six months.

August 1752: The Querelle des Bouffons breaks out in Paris

The Querelle des Bouffons had been simmering for a while, especially after an essay was written by Jean-Jacques Rousseau, but things really heated up when an Italian touring group showed up. The troupe’s performance of Pergolesi’s “La Serva Padrona,” which looked far from the French reference of the moment, Rameau, was a huge hit.

His scientific understanding of music’s underlying harmony put him at odds with arguments for melody’s greater significance. This dispute is emblematic of the intellectual shifts taking place at the time in France; it lasted for two years and pitted Rameau’s baroque traditionalism against the views of the encyclopedists and, most prominently, against those of Rousseau, the forerunner of Romanticism.

October 18, 1752: Le devin du village is performed before the king

The opera “Le devin du village,” (The Village Soothsayer) written by Jean-Jacques Rousseau, premiered in front of the king at Fontainebleau and was his sole major musical triumph. Rousseau’s beliefs, which confirmed the superiority of melody over harmony, seemed to gain traction in the middle of the Querelle des Bouffons. Though he excelled at philosophy, Rousseau, like Nietzsche a century later, would be remembered mostly as a minor musician.

The “Discourse on the Origin and Basis of Inequality Among Men” was published in March 1755

Jean-Jacques Rousseau writes his first substantial philosophical paper for an Academy of Dijon contest. He derives his new theory of the natural state and the social compact from the question, “What is the genesis of inequality among men, and is it sanctioned by natural law?” Instead of seeing the social compact as a force for peace, as Hobbes did, he sees it as a way to maintain unequal power structures.

Rousseau’s “Social Contract” was published in 1761

In an attempt to have his book “Social Contract” published, Jean-Jacques Rousseau is met with rapid censorship.

The initial release of Julie; or, The New Heloise, 1761

A book titled “Julie, or, the New Heloise,” was written by Jean-Jacques Rousseau and released in 1762. He writes letters to further the romance between Julie and her instructor, Saint-Preux. Beyond the tone and subject matter that fit the criteria of the sensitive book, Rousseau examines the literary medium of his fetish topics: social connections, relationships with nature, morality, virtue, etc.

1765: Victim of persecution in Motiers

Angry locals in Motiers attack the home of philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau with rocks. Worried and more paranoid, Rousseau finally fled the country the following year, when he was met with open arms by Hume in England.

At last, in 1766, Rousseau finished his Confessions

After authoring “Confessions,” Jean-Jacques Rousseau finally put pen to paper. Three years before the release of the booklet “Citizens’ Sentiment” (Le sentiment des citoyens) he began writing this autobiography. This anonymously published work by Voltaire was a scathing critique of Rousseau, focusing particularly on his treatment of his children after his desertion.

After being challenged, Rousseau decided to risk it all by engaging in “an endeavor that has never had an example and whose execution would have no imitator.” There would be no reverberation from Rousseau’s readings of the work before it was published after his death, but it would go on to become a classic of French literature.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, died on July 2, 1778

Jean-Jacques Rousseau passed away alone in the Marquis de Girardin’s house in Ermenonville. From the next day on, though, he was treated with respect, if not outright reverence. While his corpse was being laid to rest on the “Île des Peupliers,” (Poplar Island) a burial monument was being cast in the likeness of his death mask so that it could be constructed two years later.

It was on October 11, 1794, when Rousseau’s remains were brought to the Pantheon

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who was unfairly used by both revolutionaries and counter-revolutionaries, was given a national monument and could at last rest in peace in the Pantheon. Beyond their obvious political applications, Rousseau’s theses, and especially the “Social Contract,” had a significant impact on contemporary political discourse.

Indeed, Rousseau’s concept of common interest is often at the core of republican concerns. His ideas, like those of any other philosopher, defy neat classification. Even today, Rousseau’s ideas continue to spark heated debate, with some even going so far as to make the (hotly contested) connection between Rousseau and tyranny.

Sources:

- Israel, Jonathan I. (2002). Radical Enlightenment: Philosophy and the Making of Modernity. Oxford University Press.

- Li, Hansong (2020). “Timing the Laws: Rousseau’s Theory of Development in Corsica”. European Journal of the History of Economic Thought. 29 (4): 648 679. doi:10.1080/09672567.2022.2063357. S2CID 251137139.

- Damrosch, Leo (2005). Jean-Jacques Rousseau: Restless Genius. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 566.

- Cooper, Laurence (1999). Rousseau, Nature and the Problem of the Good Life. Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press