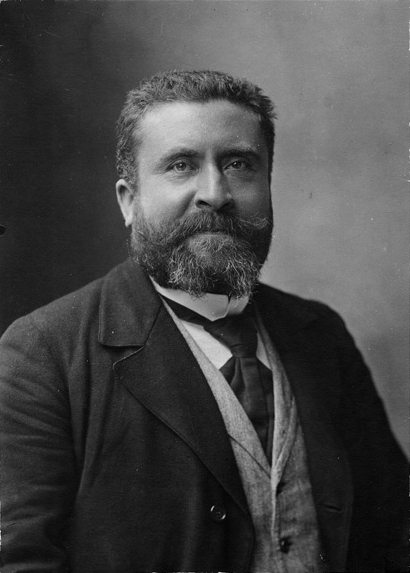

Founder of the newspaper L’Humanité in 1904 and of the Socialist Party (SFIO) a year later, Jean Jaurès embodied peaceful socialism until his assassination on the eve of World War I. Criticizing the Marxist conception of seizing power, he opposed violence throughout his life, whether in the social domain or in foreign policy. A great moral figure of the left, adorned with the ideal of humanistic socialism, he became, along with Léon Blum and Pierre Mendès-France, a source of inspiration for several generations of politicians. Upon becoming president, François Mitterrand paid homage to his tomb and inaugurated the Jean Jaurès Museum in Castres.

Note

Jean Jaurès was a key figure in French politics, serving as a member of the French Chamber of Deputies and as leader of the French Socialist Party. He was known for his impassioned speeches and efforts to promote social reform and progressive policies.

Jean Jaurès’ Political Beginnings

Born in Castres in 1859 and from a bourgeois family, Jean Jaurès achieved brilliant academic success, which led him to join the École Normale Supérieure in Paris. Subsequently, he taught as a philosophy professor at Albi High School before being appointed lecturer at the Faculty of Arts in Toulouse in 1883.

His political career began in Tarn, where he was elected as a deputy in 1885. Initially a Republican, he converted to socialism around 1892, under the influence of Lucien Herr and following the Carmaux miners’ strike. As an independent socialist deputy, he quickly made a name for himself through the warmth of his rhetoric and his exceptional erudition.

When the Dreyfus Affair erupted, he initially believed in Alfred Dreyfus’s guilt and denounced the leniency of the verdict.

Shortly after the publication of Zola’s “J’accuse” and the revelation of forgeries produced by the captain’s superior, Jaurès passionately engaged in the defense of Alfred Dreyfus, in the name of humanism and against the arbitrariness of institutions such as the army. He gained national prominence as a result.

The Rise of French Socialism

Following the bloody strikes during which the government intervened against the workers, the socialist movement split into two factions: the French Socialist Party of Jean Jaurès and the Socialist Party of France of Jules Guesde. Jaurès emerged victorious in the legislative elections of 1902 against the Guesdists.

Re-elected in 1906, 1910, and 1914, he dominated the left throughout this period. For the unification of the Socialist Party, mandated by the Second International (1904), he had to accept condemning any collaboration with the bourgeoisie, which blocked any governmental participation.

In 1908, the new Socialist Party (French Section of the Workers’ International or SFIO) entrusted him with the effective leadership of the party. As the founder of the newspaper L’Humanité, he sought to establish the human and cosmopolitan truth of rational order. A synthetic genius, he sought to reconcile idealism with materialism, individualism with collectivism, democracy with class struggle, and the nation with the international. Under his strong leadership, the Socialist Party made rapid progress.

Jaurès: A Figure of Peace

Jaurès had the intimate conviction that republican stability depended above all on maintaining peace. However, in light of this pacifist ideal, the rise of the extreme right in France and international tensions prompted him to take an unusually firm stance; he feared that the triumph of capital would lead to the collapse of democracy into war. Thus, he opposed the very principle of war, a situation contradictory to his universal fraternalism.

The increasing influence of capitalism, which former political friends such as Georges Clemenceau and Aristide Briand embraced, led him to believe that only well-organized workers’ internationals could resist the grip of capital on the global economy and the dangers that capitalist competition posed to peace. His pacifism then prompted him, in vain, to try to obtain from the International Congresses a motion capable of preventing war (Stuttgart Congress in 1907, then Copenhagen in 1910).

From 1910 on, Jaurès worried about the rise of nationalism in Europe and the growing risk of a generalized war. While promoting the establishment of a defensive army involving the entire population, Jean Jaurès opposed the law of three years, which extended active military service. He encouraged German socialists to organize a general strike in armament factories in case of a war threat. His famous speech at the extraordinary Congress of Basel International (1912) provoked the outrage of nationalists. Jaurès emphasized the absurdity of an armed conflict that capitalists wanted at the expense of the underprivileged.

On July 25, 1914, as war loomed in Europe, Jean Jaurès again made a fervent appeal for peace: “At the moment when we are threatened with murder and savagery, there is only one chance for the maintenance of peace and the salvation of civilization, and that is for the proletariat to gather all its forces and for French, English, Germans, Italians, and Russians to unite so that the unanimous beating of their hearts drives away the horrible nightmare.”

In vain. Raoul Villain, a young fanatic, assassinated Jean Jaurès on July 31, 1914, at the “Café du Croissant” in Paris. Shortly after, Germany declared war, and on August 4, the socialists rallied to the Union Sacrée, a sort of truce among parties established to face the conflict. The war broke out a few days later.

The Legacy of Jean Jaurès

When the Left-Wing Coalition decided, in 1924, to pay homage to Jean Jaurès by transferring his ashes to the Pantheon during a grandiose popular ceremony, it was to solemnly celebrate its own victory after five years of the “Blue Horizon” parliament. However, since then, the partisan hue of Jaurès’ pantheonization has faded, and the man has entered into the collective memory of the Republic, becoming a mythical figure of the 20th century.

All people praised Jean Jaurès, even his opponents like Maurice Barrès.

The icy retaliation of the Spanish Republicans is proof that he enjoyed the respect of his contemporaries and had an impact on several generations of men from all walks of life in France and abroad. His renown undoubtedly stems from the fact that his character—a blend of pragmatism and humanism, integrity and inflexibility—can be considered a model of republican integrity.

The example of his unwavering commitment to democratic institutions transcends political divides because it embodies a non-passionate version of the brilliant republic of the “professors,” the very one that allows, despite the dysfunctions of the Third Republic, the perpetuation of the republican regime. Georges Pompidou, a right-wing man, former student of the École Normale Supérieure and teacher, did not declare that he had Jaurès as a political model.

A socialist intellectual, theorist of socialism (for example in Socialist Studies, 1901), a man of action driven by what Leon Blum, one of his heirs, called a “symphonic genius,” Jean Jaurès is also and above all one of the fathers and martyrs of French socialism. The synthesis he achieved within the SFIO greatly influenced the thinking of the French left.

Beyond the sudden death that gave the man a heightened aura, the myth of Jaurès and its persistence certainly stem from the fact that he always defended the marriage between the ideal of parliamentary democracy and the defense of the working class. Devoid of extremism, his project of transition, legal and respectful of individual freedom, towards the social and socialist republic inspired the actions of men such as Léon Blum, Pierre Mendès France, and François Mitterrand.