Joachim Murat (1767-1815), one of Napoleon Bonaparte‘s marshals, was known for his bravery and extravagance. He was also king of Naples from 1808 to 1815. After rising to prominence as one of the finest swordsmen and charmers of the Napoleonic period, this innkeeper’s son ascended to the throne and married the emperor’s sister. The Enlightenment ideals he defended made him a hero to Italian nationalists fighting for the peninsula’s union. Novelists would not have dared to create a character like him for a count in the 19th century due to his extraordinary fate, panache, boldness, and terrible conclusion.

Joachim Murat: Son of the Revolution

On March 25, 1767, Joachim Murat entered the world as the son of innkeepers in Labastide-Fortunière (Lot). His father, a tiny bourgeois guy, served on many occasions as consul of his town and oversaw the distribution of church funds and other public assets. Joachim, the youngest of eleven children, was always destined for a career in the church. After studying for a while at the college of Cahors, he enrolled at the seminary of Toulouse, but was dismissed in 1787 due to a dispute with a fellow student.

Joachim joined the 12th Cuirassier Regiment of the Ardennes and was stationed in the city, preferring the military uniform over the collar of a priest. His family opposed his newfound orientation and campaigned vigorously to have him fired. Joachim remained a horseman in the company of the knight Henry de Carrière. In this new universe, Joachim served as the 12th Cuirassier Regiment of Champagne in this regiment. Joachim was a marshal of lodgings when word of the French Revolution of 1789 spread around the area. Departure from his unit and subsequent return home had been mysterious.

In the Lot again, he settled in Saint-Céré as a trader and immediately rose to prominence, joining political organizations and being chosen to represent his canton at the Fête de la Fédération in Paris on July 14, 1791. Along with him, he brought back the Parisian municipal flag after attending the event.

Joachim went back to his old unit as a private despite his newfound status. It wasn’t until February of the following year, 1792, that he and two other department soldiers were officially selected to join Louis XVI‘s constitutional guard. But this corps fell well short of his expectations, and in March he publicly complained about the widespread anti-patriotism he had seen there. That guard was disbanded after he wrote to the Legislative Assembly advocating for its elimination.

Rejoining the 12th Regiment of Chasseurs, Joachim quickly rose through the ranks, first to marshal of the logis and then to second lieutenant. Between 1792 and 1793, he was a captain aide-de-camp to General d’Urre and a squadron commander in the armies of Champagne and the North.

Bonaparte’s sword

On October 5, 1795, when royalist groups marched on the Convention in Paris, he was there. At the time, he was serving under the direction of a brigadier general named Bonaparte, who gave him this directive: “Do it swiftly, and with a sabre if you have to!” As the first step in a lengthy partnership, Murat enthusiastically carried out the general’s orders and returned the instruments of his triumph to him. After being promoted to brigade commander in 1796, he served as Bonaparte’s aide-de-camp in Italy.

After making a name for himself at Dego and Mondovi, he and Junot were tasked with transporting captured enemy flags back to Paris. He returned to Italy, where he was discovered in Genoa and Livorno, on the Adige River, in the Tyrol. On September 15, while marching towards Mantoue, he was slightly wounded. General Bonaparte’s reputation as a skilled horseman was already established by the time he ended the Italian war with the Treaty of Compo-Formio. In 1797, he was in Rome while the Roman Republic was being proclaimed.

Faithful to Bonaparte, Murat was part of the Egyptian expedition. In this fantastical country, he cultivated his reputation as a swordsman since he had no interest in scientific advancements. All the major engagements were attended by him, including the landing at Alexandria, the famous battle of the Pyramids (where he did not play a major role), the battle of Gaza, the battle in front of the infamous city of Saint-Jean-d’Acre, and most notably, the Battle of Abukir, where he covered himself in glory as the commander of the army’s vanguard. As a result of his daring attack, the Turks were driven back into the water.

Bonaparte was pleased to be able to replace the memory of the naval failure at Aboukir with that of the land triumph of the same name when the Anglo-Turkish invasion plan failed. Murat was promoted to major general on the battlefield on July 25, 1799, in recognition of his victory.

When he returned to France, he was there at Bonaparte’s side for the 18 Brumaire coup (9 and 10 November 1799). As the situation deteriorated in the Council of Five Hundred, President Lucien Bonaparte called for the delegates’ dismissal. The general marched into the Council chamber with his grenadiers, yelled, “Citizens, you are dissolved!” and then, in response to the deputies’ commotion, commanded his soldiers, “Get all these people out of here!” The deputies’ side saw a mass exodus as people rushed for the doors and windows. Eventually, Lucien would muster enough support to vote for the collapse of the Directory and the beginning of the Consulate, which would result in Bonaparte assuming control of the government.

Murat was at Bonaparte’s side throughout the riots of Vendémiaire, Italy, Egypt, and Brumaire, and he saved the Emperor’s life on more than one occasion. To deny the flamboyant swordsman the hand of his sister, who was obviously head over heels in love with him, was inexcusable. Therefore, on February 20, 1800, Murat (then 33 years old) wed Caroline Bonaparte (then 18 years old) and became the son-in-law of the First Consul Napoleon.

The young spouse remounted his horse and participated in the second Italian war. After Napoleon promoted him to lieutenant general in the head of the reserve army, he also gave him responsibility over the cavalry. Napoleon I believed that Murat’s command of such a large number of mounted troops would be an effective military asset. The commander made his way across the Great St. Bernard Pass and conquered Milan. After that, he went to Marengo to see his brother-in-law and was awarded a sabre for his efforts. After spending some time at Dijon, he headed back to his favorite battlefield—Italy—to seize Tuscany and expel the Neapolitans from the Papal States. After negotiating a peace treaty with the King of Naples, he was appointed to lead the kingdom’s Southern Observation Army. He used this opportunity to grab control of Elba.

Joachim Murat could now return to France and join local politics since that the country was at peace. In 1804 he was elected president of the Lot’s electoral college and a delegate to the Legislative Body, which launched his rise to power. After that, he was named governor of Paris. When the Duke of Enghien scandal arose, he was in charge, yet he was willing to just sign the judgment order.

Murat: Marshal of the Empire

As the Empire was declared, Murat, who was present at the coronation, was awarded every title possible for his participation, including that of Chief of the 12th Cohort, Grand Eagle of the Legion of Honor, Grand Admiral, and Grand Prince. Important among the new aristocracy, he accumulated a collection of paintings in his private hotel at the Elysée.

At the resumption of hostilities with Austria in 1805, Marshal Murat was promoted to head the equestrian forces. He crossed into Bavaria and then marched straight on to Vienna, where he encountered little opposition. He used deception to convince the Austrians that an armistice had been struck, allowing him to capture control of the Danube’s crossings before they were destroyed. He proceeded to seek his share of glory beneath the sun of Austerlitz after routing a Russian army in Moravia. On March 30, 1806, he was elevated to the position of Grand Duke of Berg and Cleves by imperial edict.

Murat embraced his new position as duke seriously and moved quickly to expand his duchy by annexing places that had been returned to Prussia, most notably the castle of Wessel. Negotiating a new export tariff with Napoleon was another issue on his mind. He personally oversaw the ducal army’s clothes, ordering fabric from Damascus and picking out the colors (crimson dolmans, “doe’s belly” colored pelisses, etc.).

However, for Murat, the war was far from done; he had to charge towards the Prussians and take part in the Battle of Jena, in which the cavalry captured 14,000 prisoners. Next, he pursued the Prince of Hohenlohe until he surrendered, at which point he was able to take Stettin with the whole might of his army (16,000 troops, 60 cannons, and as many flags). However, the destruction of Prussia did not signal the end of the war, since the Russians continued to fight.

The prince traveled through Warsaw, Poland, while dressed in his bright and colorful attire (gold thread embroidery, wide amaranth-colored trousers with gold braid, yellow leather boots, a hat with white feathers, and a plume of four ostrich feathers with a heron egret). This city, where Poniatowski presented him with the sword of Stephen Báthory (the Polish king of the late 16th century), would be his home for the entire month of January. This country wanted nothing more than to be free, and its prince simply wanted to rule.

However, his brother-in-law, Napoleon, had no interest in seeing Poland restored, so he braved the elements to lead his troops in the horrible and brutal Battle of Eylau. Napoleon opted to go into combat with his cavalry and asked Murat, “Will you let us be eaten by these people?” while the outcome of the conflict remained in doubt. The enemy’s center was crushed, and the French army was rescued, all because of Joachim Murat’s decision to lead the largest cavalry charge in the history of the French Empire (which prompted Balzac to write “Le colonel Chabert”). Because of Murat’s eccentric clothing, everyone was shocked when he avoided being killed on every single charge he faced.

Murat led the attack on Eylau while dressed in a fuzzy helmet with feathers, a fur cloak, and a white leotard. Russian troops were stunned when they were defeated at Friedland, but Napoleon met the Russian Czar at Tilsit. As Murat’s extravagant attire drew attention during the celebrations, Napoleon would tell him to “Go put on your general’s uniform; you look like Franconi” (a famous theater actor).

Joachim Murat was promoted to the rank of lieutenant general by the Emperor of Spain upon his return to the Iberian Peninsula in July 1808. He was tasked with protecting strategic Spanish outposts as a safety net for Junot’s Portuguese campaign. His first order of business was to deal with the fallout from Napoleon’s deposing King Charles IV of Spain in favor of his son, Ferdinand VII, by the “guetapens” (ambush) of Bayonne.

The citizens of Madrid revolted and began attacking the French troops. The Mameluke inspired fear among the rebels even as they stoked the flames of their animosity, and the city was soon in flames. Murat’s harsh repression was the only way he could restore order. Francisco Goya painted this scene to commemorate the historic events of “Dos y Tres de Mayo.”

When the Bourbon dynasty in Spain tore itself apart, the throne became available to whomever claimed it, and the Prince may have believed at that point that he had a valid claim to power in the city he had just conquered. However, this did not occur, and Joseph Bonaparte, the former king of Naples, regained control of Spain. When Murat was asked to choose between the crowns of Naples and Portugal, he chose Italy since he had previously served as a commander there.

Murat was relieved to see Savary arrive and assume control of Spain until Joseph Bonaparte could get there. He had now reached his breaking point; he could not bear to order against the national spirit of a people, and, what’s more, he was aware that his authority was being questioned now that another monarch had been installed. As a result of his illness, Murat had been experiencing high fevers, sleeplessness, headaches, nausea, and vomiting. Taking his family to the spa waters of Burgundy in Paris, he met his buddy Lannes before he took control of his realm.

King of Naples, Joachim Murat

King Joachim I of Naples and Sicily had widespread popular support throughout his reign. On September 6, 1808, he arrived in Naples and was greeted by the city’s triumphal arches. It’s fair to say that when his people heard that a Frenchman was arriving, they feared the worst. They saw a tall, dark-haired guy with a stellar reputation as a swordsman and ornate costumes that were spot-on for the Italian way of life enter. Whatever title Murat held in the eyes of his people, whether viceroy or grand prefect, Napoleon made it plain that Murat was only a viceroy in the eyes of him.

But Murat misunderstood and used it as inspiration to expand his dominion. He carried on Joseph’s reforms in every area, including the establishment of a national flag and army, the easing of conscription, the founding of a polytechnic university, the introduction of civil status, the publication of a new civil code, the suppression of brigandage, the establishment of new courts of first instance, and much more.

Murat fancied himself an Enlightenment scion. As he realized he’d be helpless against the English without a fleet, he set up a school specifically for the purpose. He also began excavations at Herculaneum, a Roman city that had been obliterated by Mount Vesuvius, and set out to improve the appearance of his capital. Murat decreased ministry subsidies, streamlined tax collection, and negotiated a drop from 5% to 3% interest on the state’s debt as a result of the dire economic circumstances and the state’s mounting debt (to the great displeasure of France).

After the English mocked him in front of his capital, he had no choice but to expel them from Capri in October 1808. It was none other than Hudson Lowe, the future jailer of Napoleon on Saint Helena, who led the English forces.

It was 1810, and from his throne in Naples, King Joachim I observed the Austrian alliance and Napoleon’s marriage to Marie-Louise with skepticism. It was well known that the Austrians had their own opinions on Italy and backed the Bourbons in Naples, despite the latter’s questionable legality. Murat’s association with Italian nationalist groups was a subtle but effective way for him to further his personal objectives. For the sake of his people, on June 14, 1811, he issued an edict mandating the naturalization of all aliens who were receiving financial benefits from civil service jobs. In retaliation, Napoleon declared that all French citizens were also citizens of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies since it was a member of the Empire, even if this was not to the pleasure of the French.

Joachim Murat took over as commander of the cavalry during the Russian expedition (French invasion of Russia) despite a tense relationship with his predecessor. The enemy withdrew until the Moscow, where a bloody but ultimately fruitless fight took place, in which the king stood out. The Cossacks, in particular, looked up to Murat as a hero because of his courage and flair.

In the heat of combat, Murat raised his whip in a show of respect. Following the victory, the marshal advanced through Russia and took Moscow, but the city’s destruction caused the French army to flee. Returning to France after the uprising over the Malet incident (Malet coup of 1812), Napoleon put his faith in Murat to lead the reorganized armed forces. The latter stayed put and eventually handed over leadership to Eugène de Beauharnais so he could go back to Naples.

After returning to his realm, Murat wasted no time in opening negotiations with Austria and England. Nonetheless, he never fully abandoned Napoleon’s cause and, in 1813, joined up with the French leader to head up the cavalry. Although he saw action at Dresden, the Imperial forces were ultimately routed at Leipzig (Battle of Leipzig). His perspective shifted from that of a Prince of the Empire to that of a King, and from that point on, he regarded himself as entirely responsible for the needs of his own country. His wife, Caroline, was also an important motivating factor. He signed the peace treaty with Austria on January 11, 1814, rescuing his kingdom by betraying Napoleon.

However, the calm was only temporary. Upon Napoleon’s defeat and exile to Elba, Talleyrand advocated at the Congress of Vienna for the restoration of the Bourbon dynasty to the Kingdom of Naples. As you may imagine, Murat was anxious. There was danger in his realm. Against the Austrians, who wanted to maintain their zone of influence on the northern part of the peninsula, Murat planned to defend himself in Italy by depending on the nationalist groups, which he would be able to readily unite. Aware of the events unfolding in Elba, he knew that now was the time to win or die by following Napoleon if he returned.

Murat saw his chance to fulfill his aim of raising and unifying all of Italy with the backing of the nationalists on March 1, 1815, when Napoleon landed at Golfe-Juan. On March 18, he declared war on Austria, issuing the now-famous statement from Rimini: “A scream is heard from the Alps to the Strait of Scylla, and this cry is: the freedom of Italy!” In Italian history books, Murat was no longer just a French puppet king; instead, he was elevated to the status of national hero and a forerunner of the Risorgimento (Unification of Italy). Because of this, the figure was rehabilitated on the peninsula towards the end of the 19th century, when unification took effect, and his statue still stands in Naples today.

The king’s campaign was successful at the outset, and when the Austrians were driven back to the Po River, the city of Bologna was freed to the cheers of its citizens. However, his counteroffensive backfired, and he was eventually beaten at Tolentino and forced to withdraw and escape. Although he set off for Gaeta, the presence of the English navy prevented him from reaching his destination until he landed in France, where he remained until the Bourbons reestablished their rule over Naples. His wife Caroline, who had sought safety on an English vessel, saw the acclaim bestowed upon the new king.

Murat: The fallen prince

Murat was back in his home country, awaiting a summons from Napoleon. The latter was preparing for battle, and when one thinks of battle, one thinks of an army; when one thinks of an army, one thinks of cavalry, and when one thinks of cavalry, one thinks of Murat. But his wait was in vain since Napoleon never called him, and it was Michel Ney who spearheaded the cavalry attacks at Waterloo (Battle of Waterloo). Many argue that a different result would have been achieved if a cavalryman of his caliber had been in charge in front of the English lines. An unprovable claim that belongs in the domain of uchronia. As the coalition troops closed in on France, Murat fled to Corsica, where he was greeted with open arms and where the soldiers rallied to support him.

After being pursued by General Jean-Antoine Verdier, Murat escaped to Ajaccio, where the National Guards were waiting to salute him. Not being a leader of the Corsican resistance was less important to him than reclaiming his kingdom. A man of great bravado, Murat was much admired. He set out with 250 soldiers on the evening of September 28, 1815, aboard the flotilla of Barbara, a former corsair whom he had elevated to the rank of Neapolitan baron and captain of a frigate. Did he conspire against his previous monarch?

Though Murat preferred to disembark at Trieste, Barbara used their hunger as an excuse to go with him to Pizzo, where he claimed to still have partisans. Unfortunately, the flotilla was scattered by a storm, and only two ships, or roughly thirty men, were able to accompany him. They expected to find partisans in Pizzo, but instead they encountered a community hostile due to the recollection of Joachim Murat’s brutal suppression of brigandage in the area. After an argument on October 8, 1815, he was captured and transported to the fort of Pizzo.

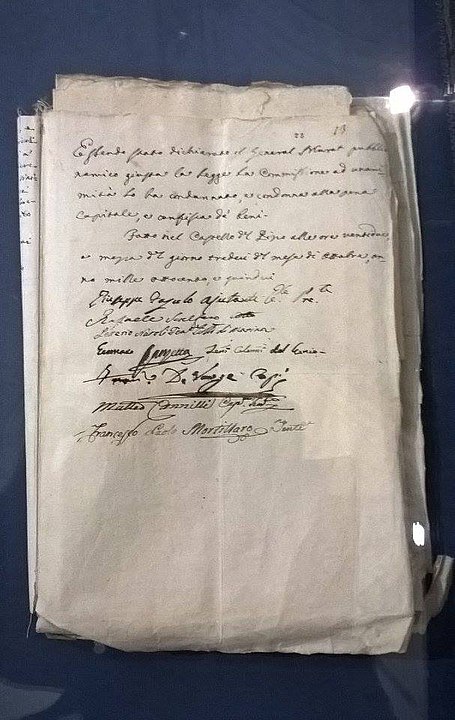

Murat, foreseeing his own death, sent a farewell letter to his wife. He flatly rejected the mock trial that was suggested for him by the Court Martial. When the Court Martial began its trial, the order of execution had already come from Naples; therefore, he was correct on this point. Upon hearing his sentence in the early afternoon of October 13, 1815, Murat had half an hour to pray for mercy before being led to the castle plaza and executed by firing squad.

Joachim Murat asked them, “Where should I sit?” with a stunning lack of complexity. Even though a chair and a ribbon were offered to him, he politely declined. He loosened his shirt to expose his chest and gave the following instructions to his executioners: “Soldiers, respect the face and aim at the heart.” He had just been struck in the chest and hand before he went down. Since he showed signs of life, the police officer gave the order to fire two more bullets. Then his corpse was added to the rest of the graves. The Bourbons may have been able to bury the corpse, but they couldn’t bury the legend of the man formerly known as “the King of the Braves and the Bravest of the Kings.”

Bibliography:

- Emsley, Clive (2014). Napoleon: Conquest, Reform and Reorganisation. Routledge. ISBN 978-1317610281.

- Fisher, Herbert A. L. (1903). Studies in Napoleonic Statesmanship Germany. Oxford: Clarendon press.

- Kircheisen, F.M. (2010). Memoires Of Napoleon I.

- Phipps, Ramsey Weston (1926). Armies of the First French Republic: And the Rise of the Marshals of Napoleon I. Oxford University Press, H. Milford.