Karabela at a Glance

What is a Karabela?

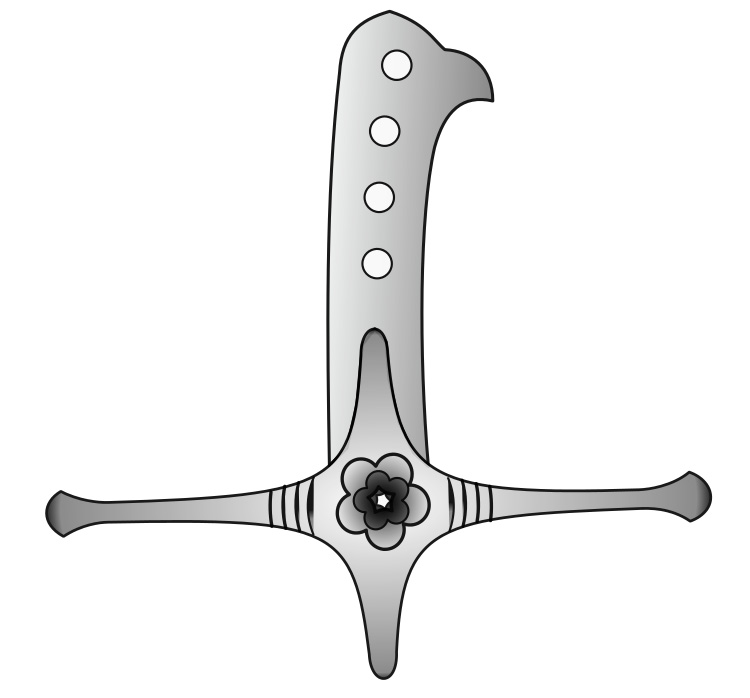

The Karabela is a Polish saber with a bird’s (or eagle’s) head-shaped crossguard and hilt. It was in use between the 17th and 18th centuries and was indicative of the Polish landscape and Sarmatism, an ethno-cultural noble ideology. The weapon had a curved blade and was known for its balanced blade and ergonomic grip, allowing for arc cuts from the wrist. Many surviving examples have rich hilt ornaments.

What are the different types of Karabelas?

There are three distinct classes of this weapon identified based on their practical significance throughout history, IIa, IIb, and IIc.

How was the Karabela used in combat?

It was optimized for arc cuts from the wrist in foot combat and swing cuts from the shoulder in equestrian combat. It allowed for protective parrying maneuvers and had a handle design that facilitated comfortable gripping and thumb placement. The curved head of the pommel prevented the weapon from slipping out of the hand, and the weapon could be spun on the palm.

What is the origin of the name Karabela?

The origin of the term is speculative, but there are several theories. One theory suggests it is a fusion of the Turkish word u0022karau0022 (meaning u0022blacku0022) and the Arabic word u0022belau0022 (meaning u0022scourgeu0022), referring to the black handle of the first Turkish variants.

Karabela is a Polish saber with a crossguard and hilt in the shape of a bird’s (or eagle’s) head. The karabela’s handle can be gripped firmly and spun on the palm for arc cuts from the wrist. Karabela was indicative of the Polish landscape, and the ethno-cultural noble ideology called Sarmatism. This cold weapon with a curved blade stayed in use between the 17th and 18th centuries. Many examples that have survived to this day have rich hilt ornaments, which were often added at the sacrifice of usefulness in battle.

| Karabela | |

|---|---|

| Type of weapon: | Saber |

| Other names: | Karabelė, Carabel |

| Origin: | Eastern Europe |

| Utilization | Military and ornamental |

| Length: | Blade: 30-34″ (77–86 cm), blade: 5″ (13 cm) |

| Weight: | Around 2 lbs (1 kg) |

History of the Karabela

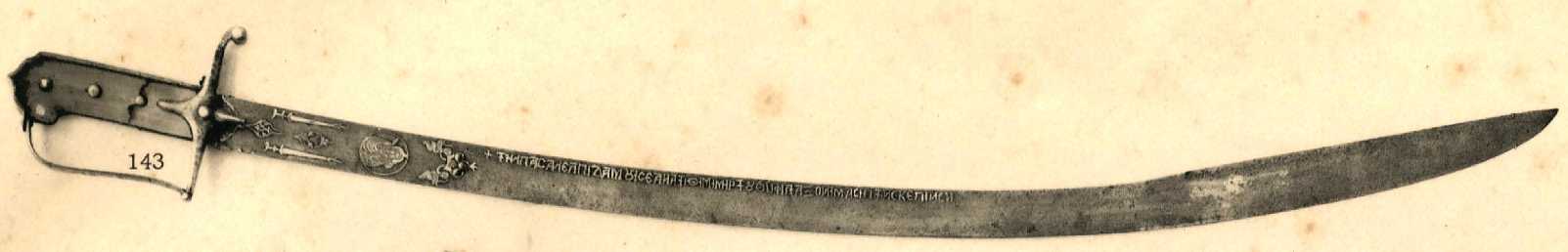

Karabela was first documented in Poland around the end of the 15th century. The earliest records of the weapon date from the military campaign against the Turks and Vlachs that the voivodships of Kalisz and Poznan cities led in 1497–1498. It was a common weapon among the Cossacks, a community with Turkic and Slavic origins.

The saber of Selim I, one of the first dated examples of a karabela, dates back to the early 16th century. Around the same period, the Ottoman Empire was also the birthplace of a unique style of this weapon.

The weapon appeared in Poland and Ukraine at the same time, and it also made its debut in Persia in the late 16th century.

During the 17th and 18th centuries, similar sabers were mostly employed by Balkan auxiliary soldiers in Turkish service, as well as in Russia, Moldavia, and Armenia. The Moroccan sabers (Nimcha, which have a smaller curved blade) were also quite similar.

The Polish karabela was revolutionary because of its balanced blade and ergonomic grip, which allowed infantrymen to make arc cuts with the flick of their wrists. Despite their superficial similarity to Western sabers, other sabers can only be used for shoulder cuts.

There are many specimens of karabela today from the 17th and 18th centuries in the Polish Army Museum in Warsaw or the National Museum in Kielce.

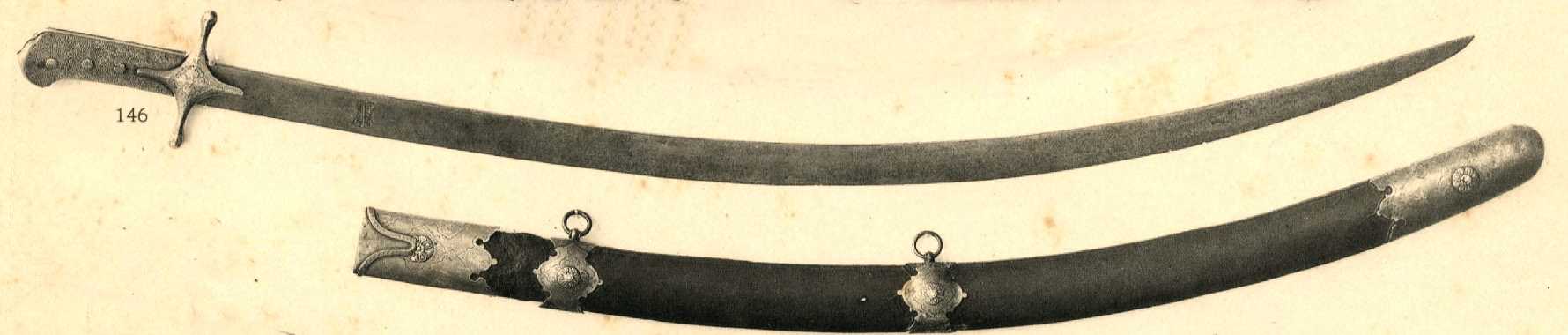

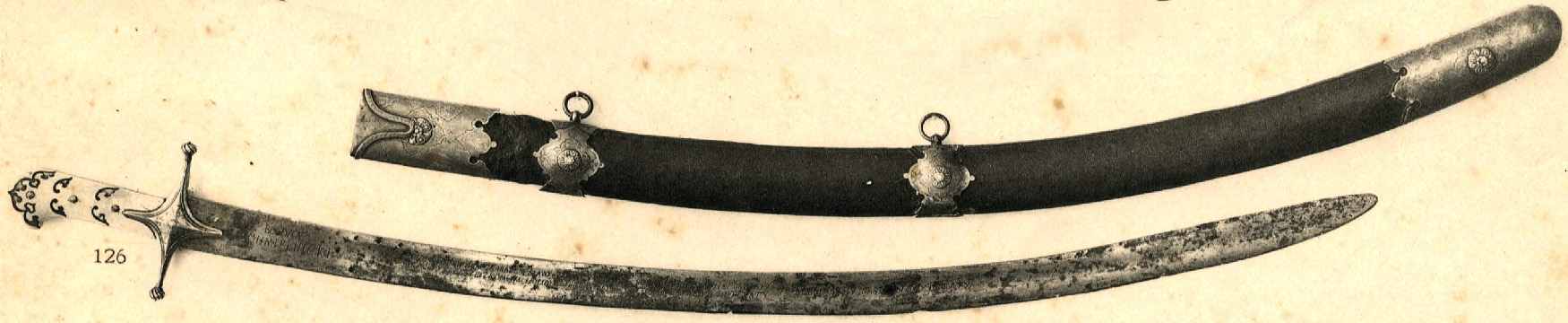

The blade length of this weapon varied between 30–34 inches (77–86 cm), with a blade curvature of 1.2 to 2.8 inches (30 to 70 mm). The length of its grip was often 5 inches (13 cm), with a small brass crossguard. There are examples embellished with miniature lion heads or ivories.

Compared to the Other Sabers

There were several different sorts of karabelas, including Polish, Turkish, Persian, Solingen, Italian, and Austrian.

There are certain subtle functional characteristics that make the Polish variant superior to comparable sabers from other countries when it comes to cuts made with the wrist:

- The blade features a double-edged curved blade, clearly marked by a prominent fuller occupying one-third of the blade’s length.

- The blade or tang, expanding towards the pommel, is equipped with notches and rivets, ensuring a more secure grip.

- The curved head of the pommel allows for the hooking of the little finger.

- The pommel noticeably expands, enabling rotation of the hilt in the palm.

Usage of the Karabela

Karabelas were optimized for arc cuts from the wrist in foot combat (types IIa and IIb) and swing cuts from the shoulder in equestrian combat. This edged weapon also allowed protective parrying maneuvers.

When performing a cutting motion with the wrist, the thumb could rest comfortably on the rear of the karabela’s handle because of how the handle was designed.

The thumb was placed along the edge of the hilt for use in shoulder cuts when mounted on a horse. Fencing with the karabela was made easier because of the pommel in the shape of a bird’s (eagle’s) head and a beak (at the end), which kept the weapon from slipping out of the hand.

The saber’s curved head made it possible for the palm spin, in which the weapon spins on the palm of the hand.

The Origin of the Name

The origin of the term karabela is a topic of speculation. However, the mainstream theory suggests that the name is a fusion of one Turkish “kara” (meaning “black”) and one Arabic term “bela” (meaning “scourge”), which means “black scourge.” The name is associated with the color of the handle of the first Turkish combat karabela, made of black horn.

Considering the effect of Turkish weapons on Eastern European nations as well as the saber being a Turkic-Mongol weapon, this explanation makes the most sense.

There is also an alternative theory with Latin or Italian roots. Some have speculated that the name was derived from the Latin terms for “precious” (cara) and “beautiful” (bella). The idea is that the weapons were often richly decorated.

But there is more to it. According to Polish historians, the name comes from the Polish lord Karabela, who is credited with introducing the use of a small, ornamental saber as part of the official court costume. In another version, Carabel is an Italian man who presented the first karabela to the Polish royal court.

But the name may have also been taken from places in Turkey, Crimea, Iraq, or Iran where these weapons were produced. One theory (according to Zygmunt Gloger) centers on the Iraqi city of Karbala. Among them is also the Turkish town of Karabel, in the vicinity of İzmir or the Karabel district in Crimea.

According to the last theory, the name might be derived from an Indo-Slavic proto-word that is related to the Sanskrit term karavala, which meant “sword” or “scimitar.” It might also come from the Arabic “carab” (“weapon”).

Characteristics of the Karabela

According to their practical significance throughout history, three distinct classes of karabelas are identified:

- Type IIa – mostly from the 17th and early 18th centuries; characterized by a broad blade with varied curvature and a fuller; and ergonomic handle that widens toward the pommel.

- Type IIb – primarily circular blade, without a broadening blade, ergonomically flat handle, from the second half of the 18th century.

- Type IIc: blades that are short and broad; ergonomic grip expanding toward the pommel; small, symmetrical crossguard with a downward curve; from the 17th and 18th centuries.

Adorned Karabelas

The bird’s head hilt provided a great opportunity for goldsmiths to show off their skills on a karabela. Yet due to the impracticality of the hilt, the most elaborately adorned weapons were of little use in battle. But it was standard practice to adorn an older blade with a bulky and decorative frame.

Materials including ivory, horn, bone, Damascus steel, gold, and inlaid wood were utilized to create an ornamented karabela.

The House of Radvilos grinding business in Jankowice, near Naliboki, was active in the second half of the 18th century, and they created easily recognized and aesthetically pleasing karabela handles made of chalcedony and other semi-precious stones, frequently encrusted.

Karabela in Culture

A Fashion Weapon

It wasn’t until the 18th century that the karabela became a “costume weapon” of the Polish aristocracy. Some of the reproductions even included elaborate embellishments of gold, silver, and gemstones. Having this weapon was almost synonymous with being a member of the aristocracy, and the curved blade was frequently carved with a statement befitting its wearer.

In its lifetime, hundreds of thousands of decorative karabelas were manufactured in Poland.

In Video Games

- In Witcher 3: Wild Hunt DLC named Hearts of Stone, chieftain Olgierd von Everec is shown wielding a karabela.

References

- A Knight and His Weapons / Edition 2 by Ewart Oakeshott, 1998 – Barnes & Noble

- The Use of Medieval Weaponry by Eric Lowe, 2020 – Google Books

- Dzieje szabli w Polsce by Włodzimierz Kwaśniewicz, 1999 – Open Library