The French Revolution, which erupted in 1789, was a period of profound social and political upheaval in France. It was characterized by the overthrow of the monarchy, the Reign of Terror, and the rise of radical political factions. The Law of Suspects, a significant legislative measure, emerged during this turbulent era. The Law of Suspects, enacted in 1793, played a pivotal role in the radicalization of the Revolution.

Origins and Implementation of the Law

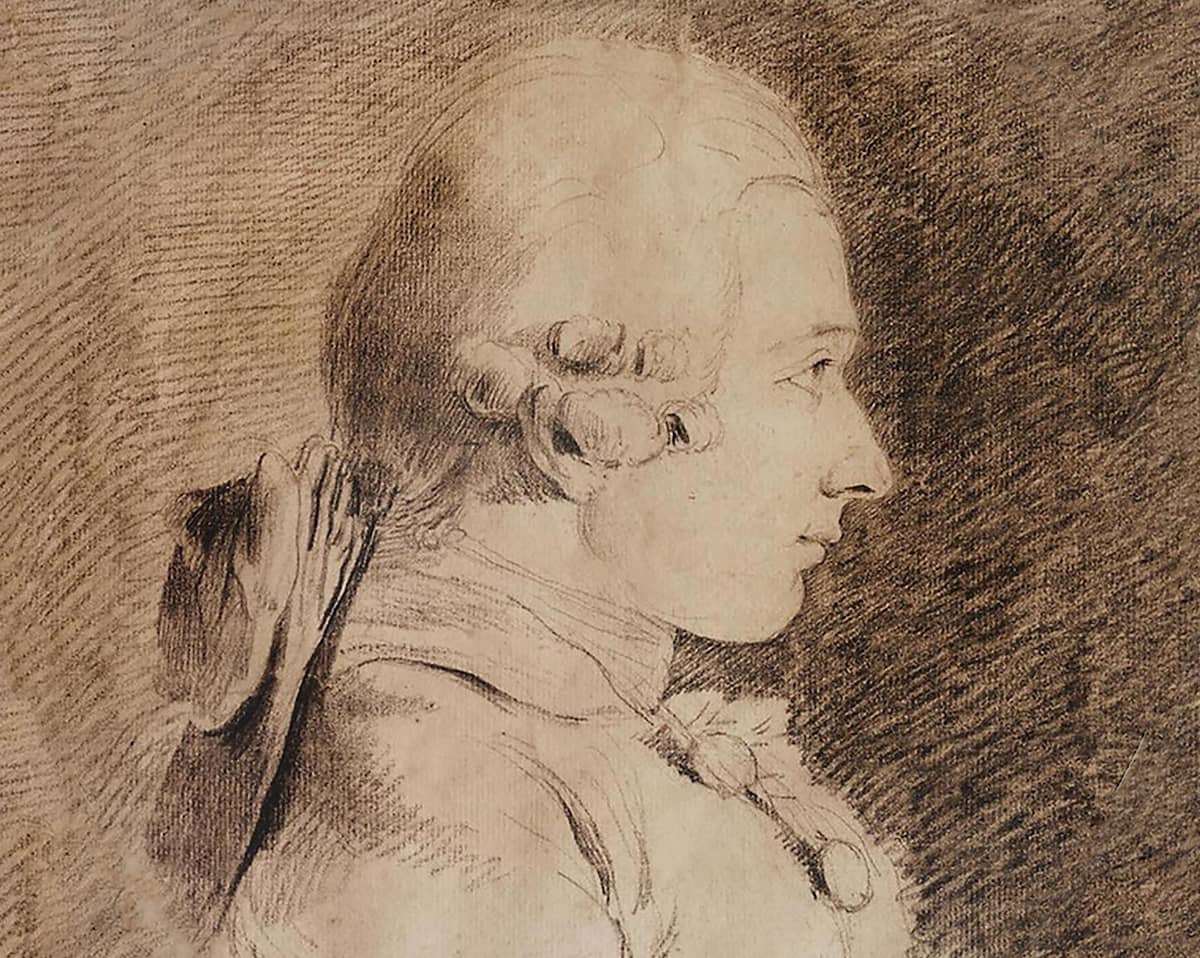

To understand the genesis of the Law of Suspects, it is imperative to examine the creation of the Committee of Public Safety. Created in April 1793, the Committee was designed to centralize power in a time of crisis. It was charged with the responsibility of protecting the Revolution and combating both internal and external enemies. Led by figures such as Maximilien Robespierre, it wielded enormous authority in revolutionary France.

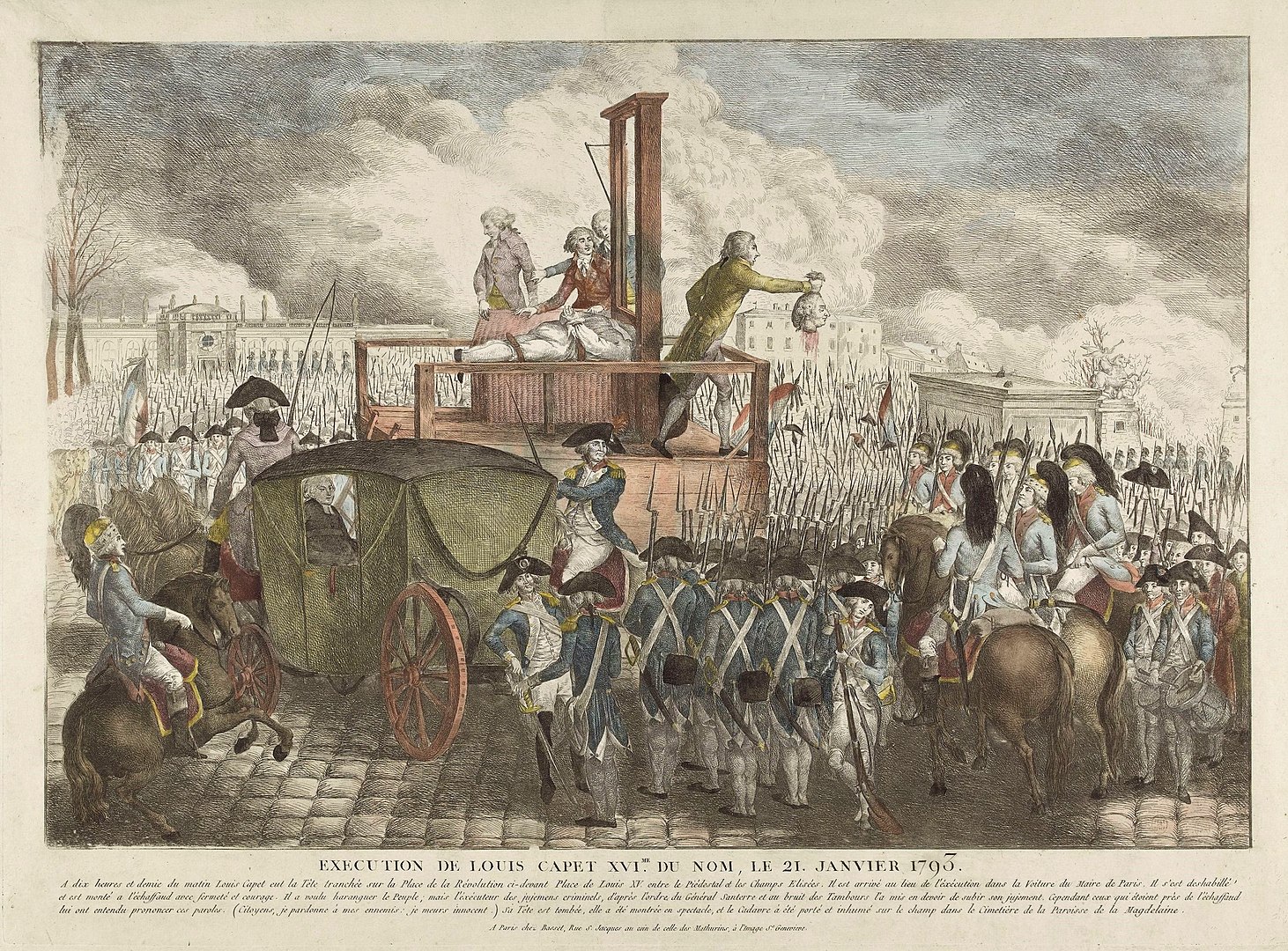

The Law of Suspects emerged as a response to growing political tensions and perceived threats to the Revolution. It was introduced on September 17, 1793 as a legal measure to identify and eliminate potential enemies of the Revolution. It expanded the powers of the Revolutionary Court and authorized the arrest and prosecution of persons suspected of counterrevolutionary activities.

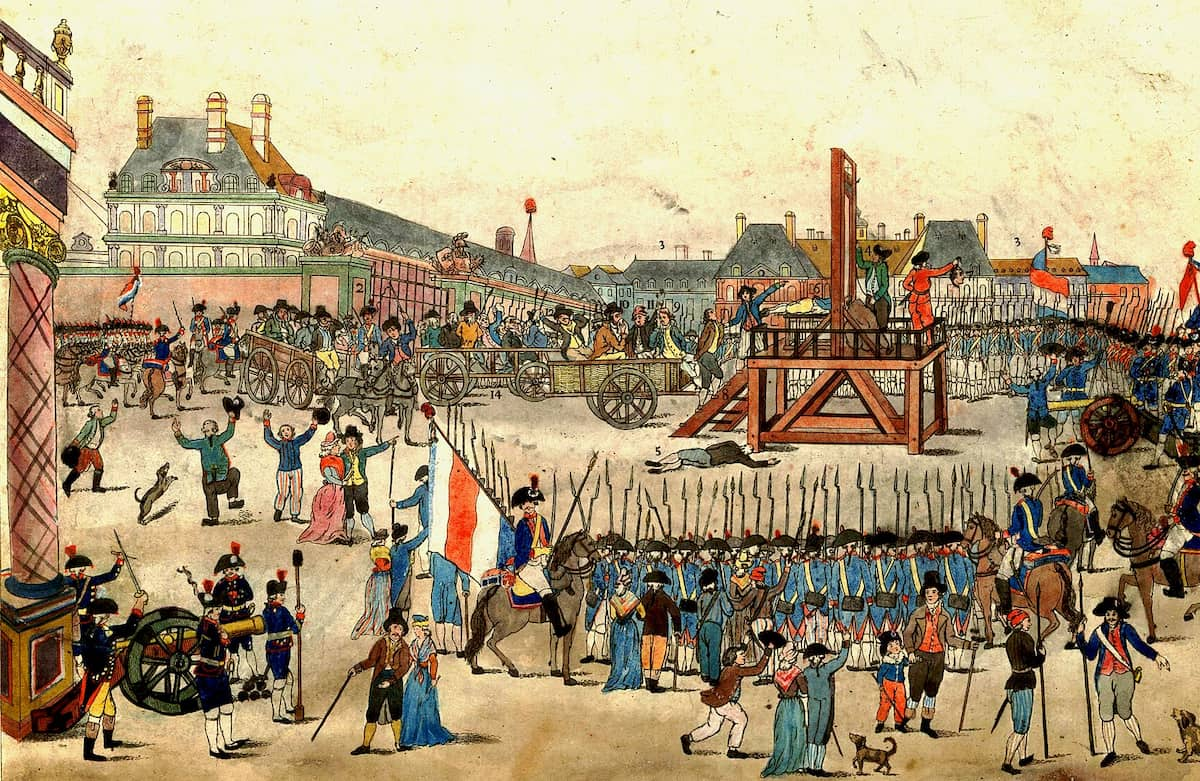

The implementation of the Law of Suspects was followed by a wave of arrests and trials. Accused individuals faced courts that often favored revolutionary zeal over due process. Suspects were subjected to a range of criteria, including their political affiliations, activities and expressions of loyalty to the Republic. The Reign of Terror, characterized by a climate of fear and political repression, resulted from the implementation of the law and caused significant social upheaval.

The Fundamental Provisions of the Law

The Law of Suspects provided a broad and somewhat vague definition of who could be considered a suspect. This definition encompassed individuals who displayed signs of not supporting the Revolution, failing to provide sufficient support for revolutionary principles, or being perceived as enemies of the Republic. This inclusive definition left room for interpretation and contributed to the widespread enforcement of the law.

Another significant aspect of the law was the establishment of Surveillance Committees. These committees were tasked with identifying and reporting suspects within their communities. The role of these committees played a crucial part in the enforcement of the law and the arrest and trial of individuals accused of counter-revolutionary activities.

The Law of Suspects outlined the main legal procedures for the arrest and trial of suspects. However, these procedures were often rushed and provided limited legal protection for the accused. The punishments imposed on suspects ranged from imprisonment to execution, with the severity of the punishment generally dependent on the perceived threat the suspect posed to the revolutionary government. The provisions of the law, particularly those related to punishments, reflected the radical nature of the French Revolution during that period.

Role in the Fall of Robespierre

Although the Law of Suspects was designed to weed out counter-revolutionaries, it faced significant criticism and opposition. Many within the revolutionary government believed that the law’s criteria for suspicion were too broad and open to abuse.

Maximilien Robespierre, a key figure in the Committee of Public Safety, staunchly defended the Law of Suspects. His support for the law stemmed from his belief that it was a necessary tool to protect the Revolution from internal and external enemies.

Ironically, the law Robespierre supported would play a role in his downfall. The Law of Suspects contributed to the atmosphere of suspicion and paranoia in Revolutionary France. Robespierre himself would eventually become a target of the law and would be arrested and executed during the Thermidorian Reaction.

With the fall of Robespierre and the Jacobins, the excessive fervor of the French Revolution subsided. The Law of Suspects in particular came under scrutiny for its role in the excesses of the Reign of Terror. In late 1794, the law was repealed and its application gradually declined. However, the scars of this turbulent period remained and France faced the challenge of rebuilding a stable society.

The Law of Suspects is a grim reminder of the extremes to which political ideologies can be carried in times of revolution. It highlights the dangers of using general accusations and collective punishment as a means of political control. Although the law was eventually repealed, its legacy has continued to influence the course of French history and provides valuable lessons about the importance of protecting individual rights and the rule of law in times of political turmoil.

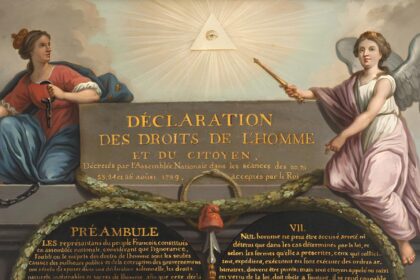

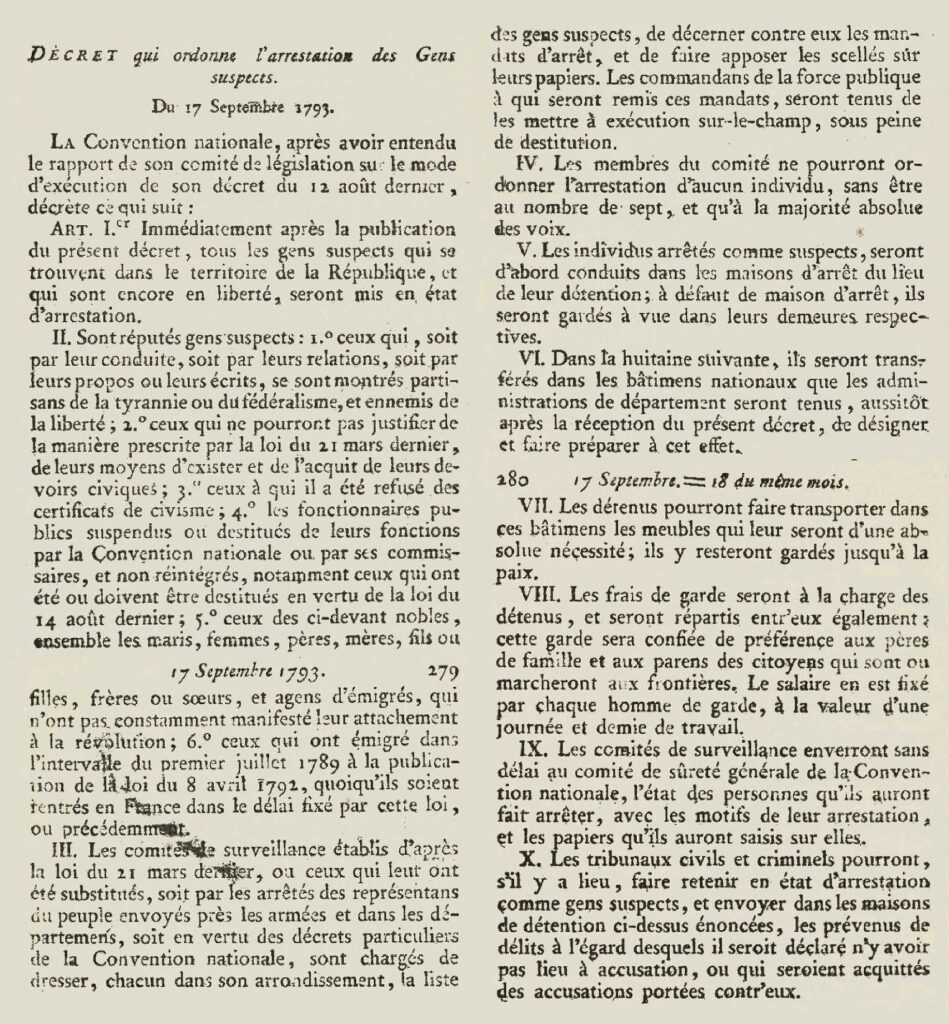

Articles of the Law of Suspects

The law is divided into ten articles. Article 1 orders the arrest of all suspicious individuals who are present on the territory of the Republic. Article 2 defines, in a very broad sense, who is to be considered suspicious:

- Persons who, due to their behavior, expressions, or personal connections, have proven themselves “as supporters of the tyrants, federalism” (referring to the Girondins), “or as enemies of liberty.”

- Persons who cannot prove the origin of their income or the fulfillment of their civic duties—referring to speculators

- Persons who have been denied citizenship.

- Suspended or deposed officials of the Ancien Régime.

- Former nobles, unless they have constantly demonstrated their allegiance to the Revolution.

- Returned emigrants.

Article 3 assigns surveillance committees to issue arrest warrants for the mentioned individuals, which the military commanders must execute under the penalty of removal. Article 4 stipulates that the committees could decide on arrests only with the majority of at least seven present members. According to Article 5, the detainees were to be initially brought to an investigative prison. If there was not enough space, they were placed under house arrest instead. Article 6 stipulates that they must transfer to one of the prisons set up by the departmental administrations no later than one week.

According to Article 7, they were allowed to bring their own necessary furniture there. The end of the detention period was set as the date of the peace treaty, of which no one knew yet. Article 8 specifies that the detainees have to bear the costs of their detention equally. Article 9 obliges the surveillance committees to report all arrests to the Security Committee. Article 10 authorizes civil and criminal courts to send individuals to the new detention facilities as suspects who have been exempt from prosecution for an offense or have been acquitted.