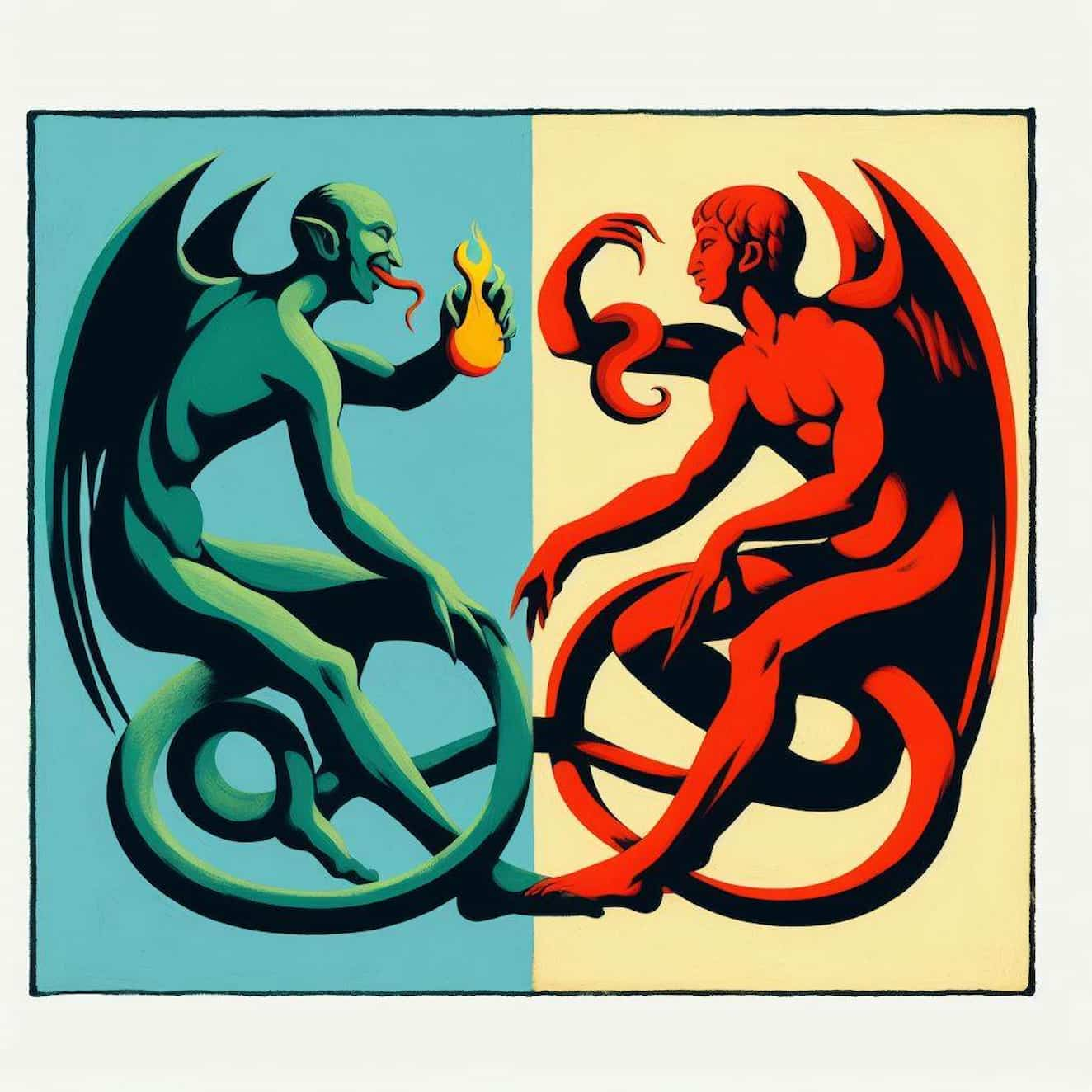

The lesser evil, or the lesser of two evils, is an ethical principle that justifies choosing one evil in order to avoid a greater evil. The condition of the principle is that of a strictly binary dilemma, meaning that there is no possibility of a third option (tertium non datur); for example, the option offered may be between the action that implies one evil and the omission that implies another different evil (which requires evaluating which of the two evils is lesser).

The impossibility of choosing between two equally attractive options is the paradox called “Buridan’s ass” (which would die of hunger and thirst if placed equidistant from food and water, unable to move in any direction). Examples of ethical dilemmas are Carneades’ table (where a castaway saves himself at the expense of causing another to drown) and the trolley problem (where one must choose to save a greater number of people at the cost of the lives of a smaller number, or vice versa).

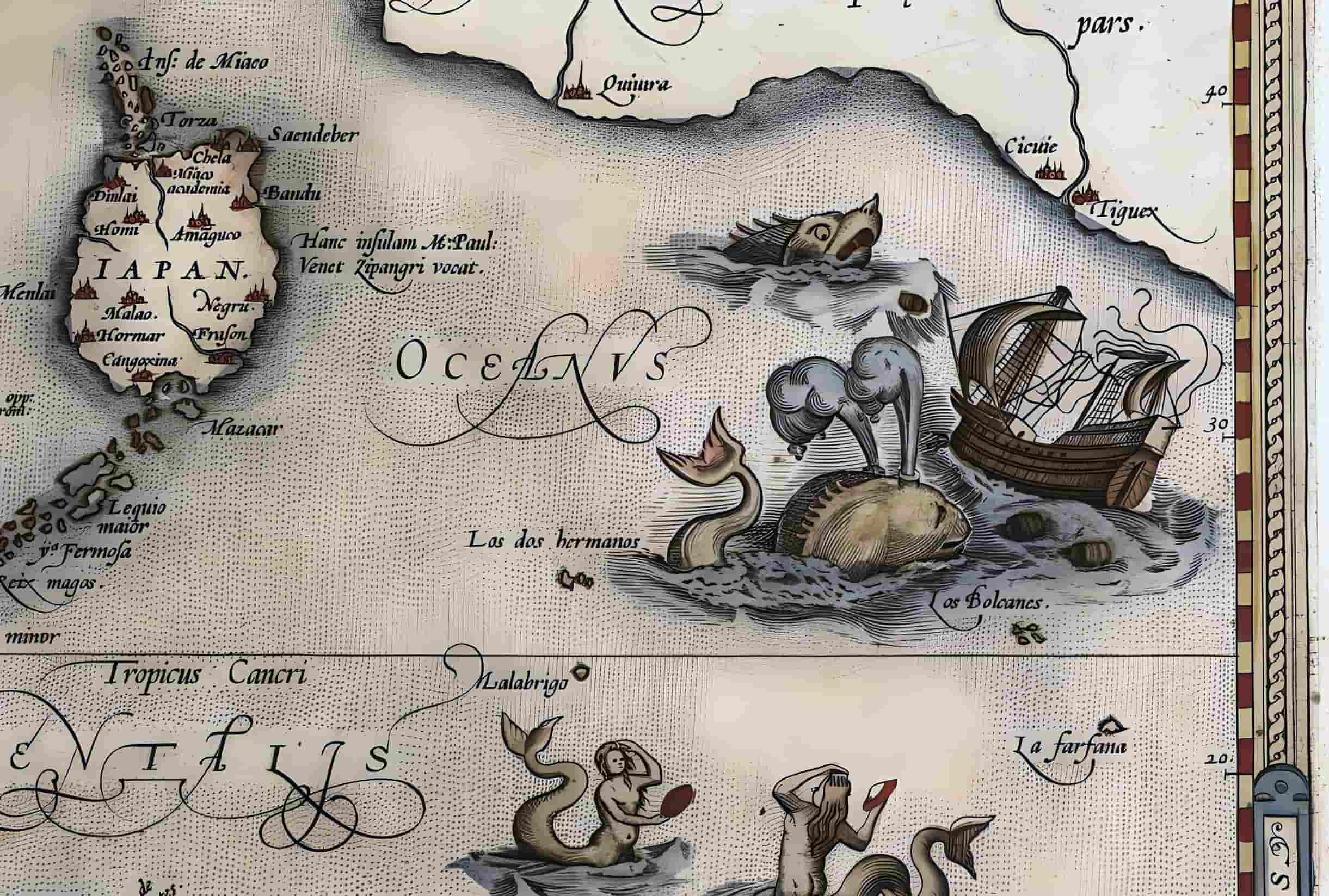

Scylla and Charybdis

The myth of Scylla and Charybdis presents the choice between two evils that Ulysses had to face; by choosing to approach Scylla, he lost six companions, but if he had sailed alongside Charybdis, they all would have perished.

Therein dwells Scylla, yelping terribly. Her voice is indeed but as the voice of a new-born whelp, but she herself is an evil monster, nor would anyone be glad at sight of her, no, not though it were a god that met her. Verily she has twelve feet, all misshapen, and six necks, exceeding long, and on each one an awful head, and therein three rows of teeth, thick and close, and full of black death. Up to her middle she is hidden in the hollow cave, but she holds her head out beyond the dread chasm, and fishes there, eagerly searching around the rock for dolphins and sea-dogs and whatever greater beast she may haply catch, such creatures as deep-moaning Amphitrite rears in multitudes past counting. By her no sailors yet may boast that they have fled unscathed in their ship, for with each head she carries off a man, snatching him from the dark-prowed ship. “‘But the other cliff, thou wilt note, Odysseus, is lower—they are close to each other; thou couldst even shoot an arrow across—and on it is a great fig tree with rich foliage, but beneath this divine Charybdis sucks down the black water. Thrice a day she belches it forth, and thrice she sucks it down terribly. Mayest thou not be there when she sucks it down, for no one could save thee from ruin, no, not the Earth-shaker. Nay, draw very close to Scylla’s cliff, and drive thy ship past quickly; for it is better far to mourn six comrades in thy ship than all together.’

Homer, Odyssey, book XII. The words are spoken by Circe.

The Latin phrase incidit in Scyllam cupiens vitare Charybdim (fell into Scylla while wanting to avoid Charybdis) became proverbial, with a similar meaning to expressions like “out of the frying pan into the fire,” “escape the fire only to fall into the coals,” or “between a rock and a hard place.” Erasmus includes it as an ancient proverb in Adages, although its earliest appearance is in Alexandreis, a 12th-century Latin epic poem by Gautier de Châtillon.

History of philosophy and law

The principle of lesser evil apparently contradicts other ethical principles that would seem to indicate that it is never permissible to commit any evil, such as those posed about injustice (αδικία adikía) by Plato, in the mouth of Socrates, in the dialogues Gorgias (it is preferable to suffer injustice than to commit it), and Crito (injustice should not be committed even to avoid a greater injustice). In contrast, the principle is clearly defended by Aristotle in Book II of his Ethics, whose Latin version spread in the 13th century in Western Europe and was also adopted by Thomas à Kempis: De duobus malis, minor est semper eligendum (of two evils, the lesser must always be chosen).

Aristotle defined virtue as a mean between two vices; proposing that it is advisable to fall into the less erroneous vice rather than the more erroneous one when one cannot hit the virtue (ta elachista lepteon ton kakon -“one must take the lesser of two evils”-). Cicero, in De officiis, gives as an example of choosing the lesser evil (minima de malis) not an easy way out but an example of heroism: the physical suffering that Marcus Atilius Regulus chose to endure in order to avoid breaking his oath.

In the Middle Ages, the principle is reflected in Ivo of Chartres and in the Decree of Gratian, which is supported by texts such as this one from the Eighth Council of Toledo: si periculi necessitas unum ex his temperare compulerit, id debemus resoluere quod minori nexu noscitur obligari (“if an inexcusable danger compels us to perpetrate one of two evils, we must choose the one that makes us less guilty”); with that wording, it is evident that, although there is a moral obligation to inflict the lesser evil, the fact that there is an obligation to do so does not exempt from guilt or responsibility, since it is still an evil. As for the way to distinguish which of the two evils is lesser, there is an inconsistency among the manuscripts that contain the text of the Council: in one it says purae rationis acumene (“by the sharpness [clearness] of pure reason”) and in another orationis acumene (“by the sharpness [clearness] of prayer”).

Electoral systems and psychological techniques

In political elections, especially in two-party systems, the options offered to the voter can both be seen as bad, so casting a vote usually does not mean identifying with a candidate considered optimal, but rather avoiding the candidate considered worse. In such contexts, expressions like “strategic voting” or “holding one’s nose while voting” are used.

There are theories and psychological techniques used in marketing and political campaigns (decision theory, neuroeconomics, and neuropolitics) that seek to guide consumer or voter preference by presenting comparative advantages or disadvantages. When not only the possibility of choosing between two options is posed, presenting a third instrumental option, closer to one option than to another, ensures that the preference leans in the desired direction.

Bioethics and medical ethics

The amputation of a foot to avoid greater harm (losing the entire leg or life) is a lesser evil assumed in medical practice, which is even expressed in a topic applicable to any other circumstance: “cutting out the unhealthy part.”

An important question is the possibility of applying the principle or criterion of the lesser evil in bioethical decision-making and medical ethics.

To admit techniques like amputation, even for those who refuse to justify the principle of the lesser evil, a resort is made to differentiate between “physical evils” and “moral evils.” According to moral rigorists, only physical evils could be subjected to a weighing of which evil is lesser, something impossible between two moral evils (absolute evils), while between a physical evil and a moral evil, the physical evil should always be preferred.

Justification of War as the Lesser Evil

While some aspects of ancient civilizations manifest a consideration of war as a good in itself or an honorable activity, others show it as an evil to be avoided as much as possible, but one must be aware that it cannot always be avoided (si vis pacem, para bellum). This is the case in the Greco-Roman world: according to Titus Livius, the Roman king Tullus Hostilius, despite his warlike nature, “calls the gods to witness that the calamities of this conflict [against the Albanians] will fall upon the people who first refused to listen to the demands of the ambassadors.” Cicero condemned the formalism that the rules of the ius fetiale imposed regarding the justification of the causes of war, proposing defense and revenge as the only just causes; although in some cases, he also proposes that war can be undertaken to “enlarge the boundaries of peace, order, and justice.”

Illa injusta bella sunt quae sunt sine causa suscepta, nam extra ulciscendi aut propulsandorum hostium causam bellum geri justum nullum potest (“wars undertaken without reason are unjust, for no war can be waged justly unless for the purpose of repelling or avenging an enemy”).

Cicero, De Republica, III, XXIII.

… if the iniquity of the opposing party is what leads the wise to uphold a just war, this iniquity should cause regret, since it is characteristic of human hearts to sympathize… So anyone who considers with pain these calamities so great, so horrendous, so inhuman, must confess to misery; and whoever suffers them, or considers them without feeling in his soul, is erroneously and miserably deemed blessed, for he has erased from his heart all human sentiment.

Augustine of Hippo, City of God, XIX.

Christianity went from proposing radical pacifism in the time of persecutions to justifying wars when the Roman Empire was Christianized in the 4th century. From then on, the causes of just war (bellum iustum) were theorized, always to restore peace and repair the injustice received: thus in Augustine of Hippo (just wars avenge injustices) or Isidore of Seville (“to recover lost goods or repel and punish enemies for the unjust war initiated by madness or without legitimate cause”), whose ideas were collected in the Decree of Gratian. Other medieval authors who theorized about just war were Acursius, the decretists and decretalists, and Thomas Aquinas. For the latter, three requirements are necessary: legitimate authority (auctoritas principes), just cause, and right intention (intentio recta) to promote good and avoid evil. Thomism developed in a new context (that of humanism and the nation-states of the Modern Age) notably with the School of Salamanca (Francisco de Vitoria). With these Catholic thinkers, and with Protestants like Hugo Grotius and Alberico Gentili, the ius ad bellum (to wage war, there must be a just cause) was added to the ius in bello (in war, damage should be limited only to combatants, and there should be proportionality between the lives destroyed and those saved).

President Harry Truman justified the use of atomic bombs on Japan based on a calculation of lives, according to which they saved more lives than they cost, assuming that any other option to end the war would have meant a greater number of casualties on both sides, although such calculations and motivations are disputed.

… the truth is very simple: to survive, we often must fight, and to do so, we must get our hands dirty. War is evil, and sometimes it is the lesser evil.

George Orwell, Homage to Catalonia.

How can you say that a good cause sanctifies even a war? I tell you: the good war sanctifies every cause!

Friedrich Nietzsche, Thus Spoke Zarathustra, 1883-1885.

Collaborationism as the Lesser Evil

Those who denounce the moral fallacy of this argument are generally accused of aseptic moralism unrelated to political circumstances, of not wanting to dirty their hands; and it must be admitted that it is not so much political or moral philosophy (with the sole exception of Kant, who is usually accused of moral rigorism), but religious thought that has most unequivocally rejected all compromises with lesser evils. Thus, for example, the Talmud argues…: If they ask you to sacrifice a man for the security of the whole community, do not give him up; if they ask you to let a woman be raped for the sake of all women, do not let her be raped. … John XXIII … “never to act in collusion with evil in the hope that, by so doing, they can be of use to anyone.”

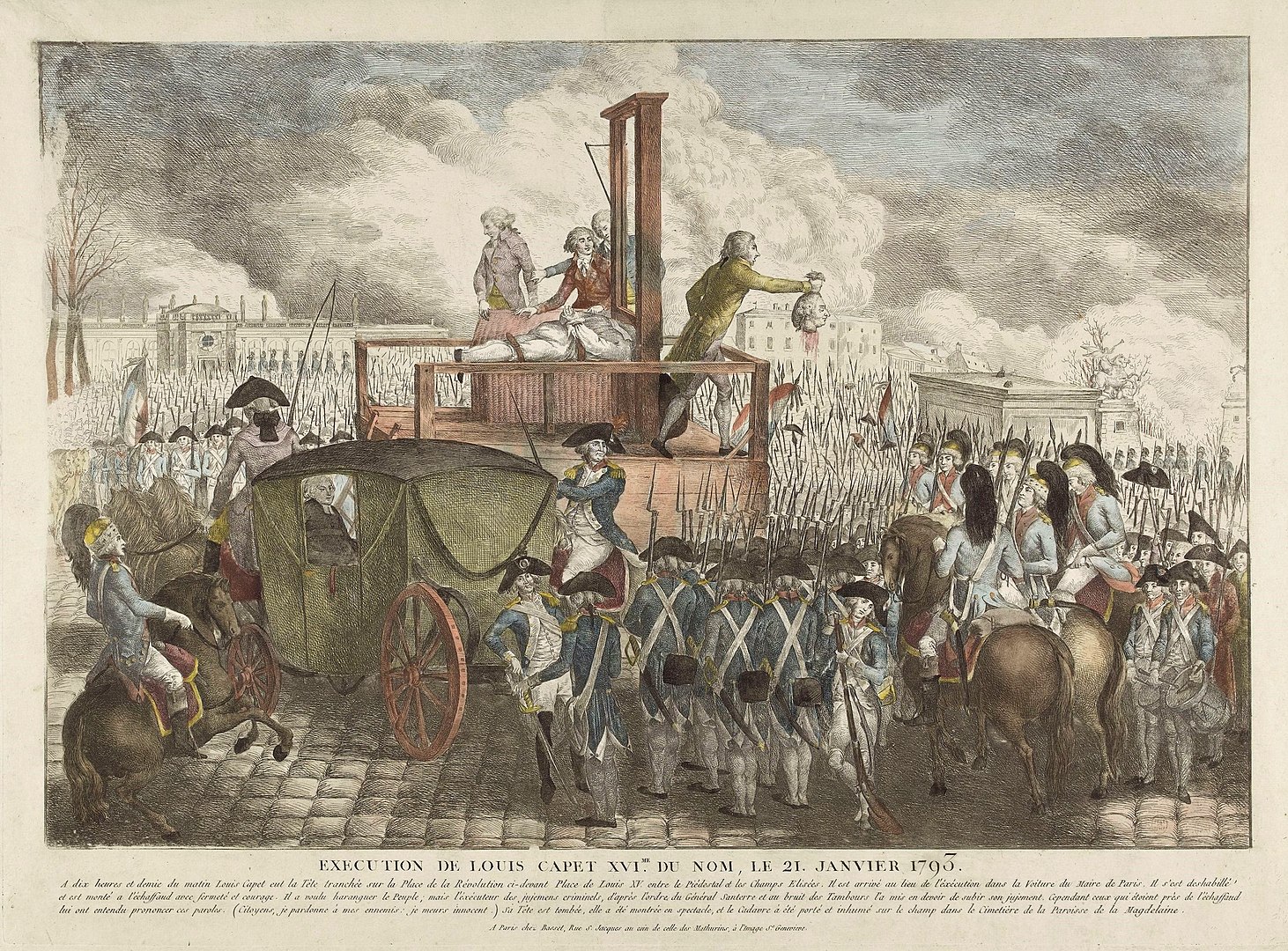

Politically speaking, the weakness of the argument has always been that those who choose the lesser evil quickly forget that they are choosing evil. … the extermination of the Jews was preceded by a very gradual series of anti-Jewish measures, each of which was accepted with the argument that refusing to cooperate would make things worse, until a stage was reached where nothing worse could have happened.

Hannah Arendt, Personal Responsibility Under Dictatorship (1967).

Tolerance as the Lesser Evil

For those who conceive of political power as a means to achieve the “maximum moral, both from religious perspectives (“to ordain good and forbid evil,” “heresy must be punished) and from secular totalitarianism, tolerance is a concession to evil since it allows its existence. In the context of the religious wars of 16th-century France, the politiques saw tolerance as the only way to achieve social peace, and Henry of Navarre agreed to convert to Catholicism to reign over a united country (“Paris is well worth a mass”), granting with the Edict of Nantes spaces of security for the Protestants. In the field of international relations, from the Peace of Westphalia (1648) onwards, the imposition of religion ceased to be a priority for European states as it had been in the previous century.

Realism in international politics requires tolerating moral differences with allies and enemies. The “balance of terror” of the mid-20th-century Cold War implied avoiding direct confrontations between superpowers if one wanted to avoid “mutual assured destruction,” forcing a peaceful coexistence with so-called realpolitik (renouncing the imposition of one’s own principles to achieve an understanding with the adversary). Even game theory was developed to weigh the logical consequences of the confrontation between adversaries with opposing interests (in the “prisoner’s dilemma,” the possibility of voluntarily assuming a punishment to avoid a greater one by collaborating with an adversary facing the same perspective).

United with the principle of lesser evil, and as a consequence of it, we can state the principle of tolerance. This has great relevance due to the pluralistic environment of our society. In a certain sense, we can understand it as “not preventing an evil, although capable of doing so, but without expressly approving it.” Consequently, regarding truth and opinion, the stance is one of respect, while in the face of evil and error, tolerance is appropriate. We can distinguish two types of tolerance: one is dogmatic, which permits everything, as for it, everything is equal. This position cannot be sustained… [but] it continues to be supported by many thinkers, for whom the relativistic view of tolerance (the dogmatic one), often presented as ethical pluralism or the neutrality of the State, is the condition for the possibility of peaceful democratic coexistence. The other type of tolerance is practical, allowing error without approving it. That is, it focuses on fundamental ethical values for coexistence: peace, freedom, and justice to legally guarantee the demands of human dignity. This second type, with some nuances, can be admitted. It is what has been called “negative permission of evil.” Tolerance, in the strict sense, that is, as a moral principle, can be defined as follows: “in some circumstances, it is morally permissible not to prevent an evil – although capable of preventing it – in consideration of a higher good or to avoid more serious disorders.”

Traditionally, the argument of the lesser evil has been applied in social ethics within the framework of the permission by public authorities of certain evils to avoid worse evils [But when one must choose between two dangers, in each of which there is an imminent peril, it is better to choose that one from which less evil follows. Thomas Aquinas, On Kingship, I, 6]. From the 16th century onwards, this notion has been extended to the distinction between the sphere of personal ethics and the sphere of legal order and governmental action. It is then when the contemporary concept of “tolerance” arises, understood as the attitude of States accepting the primacy of individual decisions over public authorities, in less relevant aspects of the common good, gradually opening a more marked dissociation between individual morality and public order, as in John Locke in his Letter Concerning Toleration (1689), or in Voltaire with his Treatise on Tolerance (1763). However, this gradual process has not ceased to reveal its contradictions. The sophistical uses of the argument of the lesser evil, and its use in a context unrelated to the perception of the absolute ethical demands of truth about the human person and their dignity, have been denounced by contemporary thought, especially since the Second World War. Hannah Arendt has made a sharp critique of the aberrant and ideological uses of the argument of the lesser evil in an attempt to numb moral consciousness during the National Socialist period in her book Personal Responsibility Under Dictatorship (1964): “The acceptance of the lesser evil was consciously used to accustom officials and the population to generally accept evil itself.”

Justification of Torture as the Lesser Evil

Since at least Jeremy Bentham, the use of torture has been purportedly justified as a lesser evil, with the so-called “ticking time bomb scenario” (TBS): authorities have caught a terrorist who has just placed a bomb, and he refuses to provide information about its location, so there is no way to prevent the death of many people unless he is forced to do so. Alan Dershowitz argues that both evils must be analyzed, and one must be willing to accept the consequences of the choice, concluding that torturing the detainee is the lesser evil. Michael Ignatieff agrees with the approach, warning that it could only be applied as a last resort if it were impossible to resolve the emergency with other methods; but he insists on pointing out the danger of turning it into a greater evil if it is disconnected from the assumptions of the scenario (real and immediate threat) and becomes a systematic recourse (applied to suspects or for potential events), as would have happened after the attacks of September 11, 2001.

References

- de Spinoza, Benedict (2017) [1677]. “Of Human Bondage or of the Strength of the Affects”. Ethics. Translated by White, W.H. New York: Penguin Classics. p. 424. ASIN B00DO8NRDC.

- “Jill Stein cost Hillary dearly in 2016. Democrats are still writing off her successor”. Politico.

- “Chirac’s new challenge”. The Economist. 2002-05-06. Retrieved 2011-04-15.

- Schneider, William (18 September 1988). “THE EVIL OF TWO LESSERS”. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 12 September 2020.

- Keinon, Herb (6 November 2016). “Clinton vs. Trump: ‘The evil of two lessers'”. Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 12 September 2020.

- Noted by Edward Charles Harington in Notes and Queries 5th Series, 8 (7 July 1877:14).