Better known as Saint Louis, Louis IX was a king of France from the Capetian dynasty who reigned from 1226 to 1270. This sovereign is a legendary figure in the history of France and Christendom. A model prince, knight, and crusader, he ruled at the height of the French Middle Ages. Thanks to the writings of Jean de Joinville, we know a great deal about his long reign, which spanned the 13th century. Concerned with order and justice, this great Capetian king implemented numerous reforms. Deeply pious, Louis IX participated in two crusades. The failure of his ventures in the Holy Land and his death in Tunis secured his place in history and led to his rapid canonization.

Louis IX: Heir to a Dynasty at its Peak

Despite the brevity of his reign (three years), the father of the future Saint Louis, Louis VIII, secured the future of the dynasty. From his wife, Blanche of Castile, he had no fewer than eight sons. The eldest, Philippe, died in 1218, and the second, Louis, was destined for the crown, leaving the others to be provided for. In a will drafted in June 1225, Louis VIII decided that three of his sons would be granted fiefs that had been incorporated into the royal domain by Philip II Augustus. The third, Robert, received Artois, the fifth, Alphonse, received Poitou and Auvergne, and the eighth, Charles, received Anjou and Maine, in place of the fourth son, Jean, who had died prematurely in 1226, and the sixth and seventh, who had also died young.

The creation of these territorial principalities for the “princes of the fleurs-de-lis” could facilitate the spread of Capetian customs and mindsets in territories that had retained their local identity and traditions due to a long period of autonomy. Additionally, the clause stating that these territories would revert to the crown in the absence of a male heir would help reincorporate them into the royal domain. Nevertheless, this decision reduced the domain’s size by a third.

There was a considerable risk that this could lead to the rise of a new feudal aristocracy of powerful barons who, despite their close kinship, could pose an obstacle to the strengthening of the sovereign’s authority. For the moment, the royal house was wealthier, more powerful, and more prestigious than all the other great feudal families. It was obeyed, respected, and even admired from the English Channel to the Rhône and from the Rhône to the Pyrenees. Thus, the reign of Louis IX began under favorable conditions.

The Regency of Blanche of Castile

Born in 1214 (the year of the Battle of Bouvines), Louis IX was too young to rule upon his father’s death in 1226. His mother, Blanche of Castile, assumed the regency. She fought against a coalition of nobles led by the Count of Brittany, emerging victorious in 1234. Blanche also ended the crusade against the Albigensians in 1229 (Treaty of Meaux) and united the County of Toulouse with the crown.

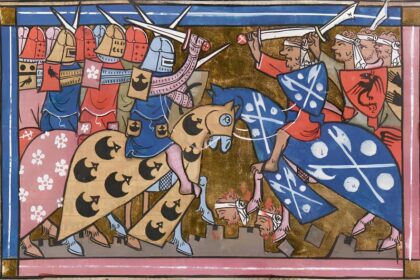

As soon as he ascended the throne, the young king faced a new feudal rebellion, led by Hugh X of Lusignan, which was swiftly crushed. King Henry III of England took advantage of the situation to invade France in 1242, but he was defeated by Louis IX at Taillebourg and Saintes. By 1243, a five-year truce had been agreed with Henry III, which was confirmed by the Treaty of Paris in 1258, where both sovereigns ceded territories to each other.

In the same spirit, Louis signed a treaty with King James I of Aragon, with the former renouncing French claims on Roussillon and Catalonia, and the latter relinquishing his suzerainty over Provence and Languedoc. Louis also intervened in the ongoing conflict between the Empire and the Pope, positioning himself as a mediator. Saint Louis was determined to stabilize the situation in Europe and with its neighbors so that he could focus on what he saw as his Christian duty: the Crusade.

Saint Louis: The Most Christian King

Louis IX was deeply marked by his intense faith, strongly influenced by his mother, Blanche of Castile. He aspired to make France the preeminent Christian nation. In this spirit, he had the Sainte-Chapelle built in 1248 to house relics such as the Crown of Thorns and a fragment of the True Cross. He also supported the Cistercians by establishing them at Royaumont in 1236.

Concerned with maintaining order and justice, he banned familial vendettas. In the same vein, Saint Louis sought to regulate private violence (issuing the 1258 ordinance on judicial duels), outlawed blasphemy, and persecuted Jews. He even went so far as to ban gambling. Haunted by the concept of sin, Saint Louis embodied the archetype of the Christian knight, generous toward the poor. His faith deeply impressed his contemporaries as he adopted an increasingly monastic lifestyle. Nevertheless, he was not without fanaticism, showing no mercy toward heretics. He supported the Inquisition in Languedoc against the Cathars (Montségur fell in 1244) and required Jews to wear the scarlet badge.

Popular imagery depicts the king as a man of fervent faith, rendering justice under the oak tree of Vincennes. Of all the duties required of him as king, those of a judge were Saint Louis’ favorite. Throughout his life, he was a just king. Joinville was the first to describe the king sitting after Mass under an oak tree, receiving all who wished to plead their cases “without obstruction from ushers.” He gave alms to the poor, healed the blind and lepers by touch, and preferred the company of mendicant friars to that of princes. Joinville reports one of his mottos: “Beware of doing or saying anything that, if the whole world knew of it, you would be unable to acknowledge, ‘I did this; I said this.'”

Louis IX Departs On Crusade

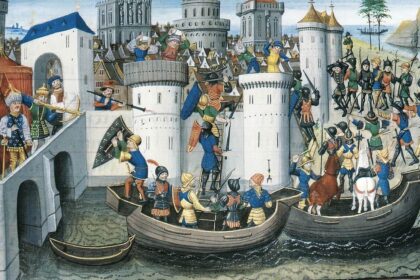

In 1244, Saint Louis was struck by illness and vowed to go on a crusade if he survived. He kept his promise and had the port of Aigues-Mortes built specifically for this purpose. After meeting Pope Innocent IV in Lyon in 1245, he left for the Holy Land, choosing Egypt as his target. The crusaders easily captured Damietta in June 1249 but delayed advancing toward Cairo. They were hindered by the flooding of the Nile and had to fight in poor conditions at Mansourah in February 1250. The king’s favorite brother, Robert of Artois, driven by reckless bravery, was killed at the vanguard along with many knights. The army was forced to retreat in desperate conditions, as a terrible epidemic decimated much of the troops.

On April 5th, the king, now sick, was captured and taken to Mansourah. Fallen into the hands of the Mamluks (who had just overthrown the Sultan), Saint Louis was in great danger, but he displayed admirable courage and even impressed his enemies during adversity. After difficult and painful negotiations, the Mamluks released him in exchange for the return of Damietta and a massive ransom of 400,000 livres. The depleted Christian army was allowed to leave Egypt, and the king made it a point of honor to scrupulously fulfill the terms he had sworn for his release.

The king did not leave the East immediately and spent the following years in the Latin states, trying to address the internal problems tearing them apart. In his fervor for the crusade, the king seemed to forget his own kingdom. However, it was facing challenges. Besides the constant threat of aggression from the King of England, France was plagued by new and peculiar troubles. A wave of mystical madness swept through the northern provinces and seemed to spread across the entire country. Shepherds, called “pastoureaux,” rose up in Flanders and Picardy, following the call of a mysterious figure known as the “Master of Hungary.” They claimed they would save the king, betrayed by his knights.

Outcasts, vagrants, and bandits joined them from all sides. Soon, they became an army of one hundred thousand men, a mob of peasants declaring war on the nobles, priests, and Jews. In Paris, Orléans, and Bourges, conflicts between the pastoureaux and the population were bloody. The regent, initially surprised by the scale and mystical nature of the movement, regained control and ordered royal officials to organize a crackdown on the pastoureaux everywhere. They were then pursued, driven toward the South, and eventually annihilated.

This was the last service rendered to the kingdom by the regent. Saint Louis received the news of her death at the beginning of 1253. However, he lingered in the Holy Land for another year, unable to tear himself away. It was only in the summer of 1254 that he finally returned to his kingdom.

Louis IX: A Reforming King

The France of Louis IX experienced significant institutional reforms. The first phase took place between 1226 and 1248: the king played the feudal card fully, winning the loyalty of the nobility while also regulating private warfare.

The second phase of his reforms occurred after his return from the crusade, partly in response to this inquiry. Deeply changed by his experience as a crusader, the king sought peace with his neighbors, Henry III of England and James I of Aragon. He then embarked on significant reforms, recruiting competent men like Gui Foulquoy.

The Curia regis was restructured in its functioning, with the king at the center, surrounded by his close advisors. From 1250, part of this court specialized in justice, laying the foundations for the 14th-century parliament. The administration was refined, tasked with relaying the numerous ordinances decided by the king. Saint Louis thus became the Capetian monarch who legislated the most.

The Last Crusade and the King’s Death

After his return, despite the numerous tasks he accomplished, the king’s daily thoughts were focused on taking up the cross again. In 1266, he finally shared his desire with Pope Clement IV, who was less than enthusiastic. In fact, Saint Louis had little understanding of Eastern affairs and even less of Muslim politics. Wounded by his previous failure, but also aware of the dangers facing the Latin presence in the Holy Land, Saint Louis once again took the cross in 1267, despite the exhaustion of the barons. Likely influenced by his brother, Charles of Anjou, who had become very ambitious since conquering Sicily, the king decided to lead the crusade against Tunis.

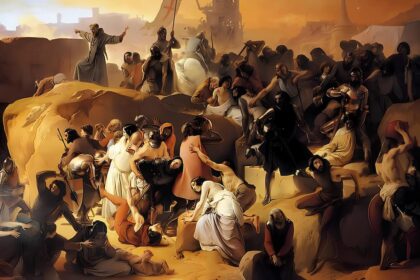

The army set sail imprudently, in the height of summer, on July 1st, 1270, from Aigues-Mortes, after waiting for a long time for the Genoese ships that were to transport the crusaders to Africa. A month later, the army was on the ruins of ancient Carthage, suffering under a scorching sun, with no drinking water and only the shade of scraggly olive trees.

The Saracens, with their war machines, sent clouds of burning sand into the French camp. Dysentery and the plague caused considerable devastation. Saint Louis’ beloved son, Jean Tristan, died at the age of twenty. The king tended to the sick until the day he himself was struck by the plague. He died on August 25th, 1270. Paradoxically, this new failure marked his glory: the Christian king died on a crusade, paving the way for his sainthood.

The Legacy of Saint Louis

The reign of Saint Louis was ultimately a period of moral, intellectual, and artistic flourishing for France across Europe, especially since it benefited from a favorable situation, without famine or epidemics. The king’s personality, his reforms, his faith, and his actions as a crusader explain why he is regarded as one of the most important kings of France, far beyond mere folklore. He was canonized by Pope Boniface VIII in 1297, just twenty-seven years after his death. His son Philip, the future Philip III the Bold, succeeded him.