Louis XIII (1601-1643) was a King of France from the Bourbon dynasty, nicknamed “the Just.” He reigned from 1610 to 1643. The eldest son of Henry IV, Louis XIII succeeded his father at the age of nine. His mother, Marie de’ Medici, served as regent. In 1624, he appointed Cardinal Richelieu as his principal minister.

- The Dauphin: Future Louis XIII

- May 1610: The Assassination of Henry IV

- The Regency of Marie de Medici and Concini

- From Luynes to Richelieu

- Louis XIII and Richelieu: Absolutism in Action

- The Era of Conspiracies

- Struggle Against the Habsburgs and the Death of Louis XIII

- The Reign of Louis XIII: What is the Legacy?

From that point, the kingdom’s policies took a new direction: together, the king and the cardinal fought against the influence of the Habsburgs in Europe and limited the power of the nobility within the kingdom. They reduced the privileges enjoyed by Protestants since the issuance of the Edict of Nantes, which reignited the war between Catholics and Protestants. Louis XIII’s reign is marked by the establishment of a strong, centralized state, ushering in France’s “Grand Siècle.”

The Dauphin: Future Louis XIII

Louis was the son of Henry IV, King of France and Navarre, and Marie de’ Medici. He was not the first-born of the “Vert-Galant” (Henry IV), known for his numerous illegitimate offspring. The marriage between Henry IV and the Florentine princess was driven by diplomatic (preserving French influence in Italy), dynastic (providing the Bourbon lineage with an heir), and financial (canceling the kingdom’s debt to Florentine bankers) reasons. Personal feelings were secondary to these calculations, and Henry IV remained infatuated with his various mistresses.

The young Queen, who came from Florence with an extensive entourage (including her confidante and lady-in-waiting, the famous Leonora Dori, wife of Concino Concini, who will be discussed later), nevertheless fulfilled the dynastic hopes of the king. She bore him six children, of whom two sons reached adulthood: Louis and Gaston (the Duke of Orléans, known as Monsieur).

Louis’ childhood is well documented in the journal left by his doctor and friend, Jean Héroard. Raised at the Château of Saint-Germain-en-Laye, Louis shared his daily life with his siblings, both legitimate and illegitimate. The child had a keen interest in outdoor activities, hunting, and the arts, particularly dance and drawing.

The young Louis greatly admired his father, who was known for his love of children. However, the relationship between mother and son was much more distant. Marie, fond of pleasures and frivolity, made little effort to adapt to France and remained under the influence of her Italian favorites, the Concini couple. Additionally, she preferred her younger son Gaston, whom she considered more graceful and intelligent than Louis, whom she found unattractive and slow-witted.

Fascinated by military life, Louis was not the most diligent student but demonstrated a certain intelligence. Despite his speech impediment (he was a stutterer) and shyness, he was aware of his status and demanded respect. There is no doubt that the example of his father, an authoritative king, greatly influenced him.

May 1610: The Assassination of Henry IV

France was on the brink of war. For both diplomatic reasons (the succession of Cleves and Jülich) and domestic concerns (the flight of the Prince of Condé to Brussels), Henry IV planned to confront the Habsburgs once again. However, he never fulfilled his plan as he was assassinated on May 14, 1610, by Ravaillac, a disturbed fanatic who may have been manipulated by the ultra-Catholic faction opposed to the war.

Louis, still a child, experienced a trauma that would haunt him for the rest of his life. His mother, who had been officially crowned the day before, became the regent of the kingdom.

The Regency of Marie de Medici and Concini

Previously uninterested in governance, Marie de’ Medici quickly developed a taste for power. Favoring the pro-Spanish and ultra-Catholic faction, the regent pursued a policy of appeasement on the international stage. She successfully arranged the marriage of the Spanish Infanta, the beautiful Anne of Austria, to her son Louis, securing peace between the Bourbons and Habsburgs. However, Marie was ill-prepared to manage a kingdom still divided.

While the Protestant-Catholic conflict persisted, the main threat to the kingdom’s stability was the Grands—representatives of the most powerful aristocratic families, such as the Condé, Guise, Nevers, and Montmorency. In times of regency, when royal authority was perceived as weak, their influence grew. Furthermore, the Grands sought to take revenge on a monarchy that relied on the nobility of the robe (the administrative class) and the rising bourgeoisie.

This burgeoning bourgeoisie, with its growing wealth, increasingly accessed high offices, which at the time were purchasable. This system of venality of office was used by Henry IV to fill the state’s coffers. In response, the aristocracy maintained its dominance by deliberately fostering instability in the provinces, even to the point of rebellion. Faced with this challenge, Marie de’ Medici was forced to buy peace through generous pensions.

Additionally, the kingdom’s financial situation suffered from the regent’s extravagant spending on entertainment and the greed of the Concini couple, who became highly unpopular. Concino Concini, a minor Italian noble, displayed excessive ambition, acquiring prestigious titles and honors through his wife’s influence over the queen. He soon became the Marquis of Ancre and a Marshal of France, amassing immense wealth and controlling ministerial careers.

Despite his unpopularity, Concini remained a royal favorite, enjoying both the queen’s affection and trust. He was a key instrument of the monarchy’s absolutist tendencies, which did not go unnoticed by the Grands. They soon denounced Concini’s influence over the queen and retreated to their provinces, sowing the seeds of rebellion.

The Grands found an unexpected ally in the young king. Although, like his father, Louis was attached to the prestige of the monarchy and disliked the nobility’s pretensions, he harbored a fierce hatred for Concini. The Italian favorite openly scorned the king and wounded his adolescent pride. When Louis appealed to his mother, he found only further humiliation. This was a dark time for the young king, who began to suffer from the illness that would plague him throughout his life—likely Crohn’s disease, a severe intestinal condition.

Despite the often unbearable pain, Louis was determined to assert himself as king. In secret, this shy and brooding fifteen-year-old prepared Concini’s downfall. He could count on the help of several supporters, notably Charles d’Albert, the future Duke of Luynes. A minor noble and France’s Grand Falconer, he had become Louis’ best friend, sharing a passion for hunting. This relationship reflects Louis’ tendency to form close bonds with male friends and father figures.

On April 24, 1617, Concini was arrested at the Louvre and assassinated by conspirators on the pretext that he had resisted. Louis, who had not opposed the physical elimination of his favorite, simply declared, “At this hour, I am king.”

From Luynes to Richelieu

This coup d’état, or “majestic coup” as it was referred to at the time, reveals the strength of character of the man taking control of France’s destiny. Louis XIII intended to be a king who ruled without sharing power. Nonetheless, with the elimination of Concini, it marked the triumph of Luynes. This new favorite, though lacking great talent, was charismatic and the primary beneficiary of the downfall of the Italian couple, taking advantage of the young king’s inexperience.

Blinded by his friendship with the grand falconer, Louis soon made Luynes a duke and peer, then a marshal (despite Luynes being a poor military leader). Such rapid success naturally led to jealousy and discontent among the nobility, as well as Queen Mother Marie de’ Medici, who saw Concini’s elimination, and especially that of his wife, as a personal affront. She held the belief that the king could not govern France without her “good counsel” and was resentful of her marginalization in Blois.

She soon took the lead of the discontented faction, gathering behind her the very nobles who had caused her so much trouble during her regency. After escaping Blois, Marie de’ Medici triggered two short civil wars, both of which she eventually lost.

At the heart of the negotiations that ended these “wars of mother and son” (from 1619 to 1620), one figure stood out: Armand du Plessis, Bishop of Luçon, the future Cardinal Richelieu. Originally one of Marie de’ Medici’s secretaries of state, the ambitious cleric skillfully maneuvered to bring peace back to the kingdom. Though Louis XIII was wary of him, he recognized that Richelieu shared his vision of royal authority and was equally hostile to religious or noble dissent. Louis would remember this…

From 1620 to 1621, the young king, having proven himself a capable captain during his recent campaigns, asserted his character and gained popularity with his people. He ended religious exceptionalism in Béarn (a Protestant state at the time) and turned his provincial travels into effective political communications. His entrances into towns were occasions to present himself as a sovereign who was both warrior and peacemaker, but above all, as a dispenser of justice—a role he cherished. He never missed an opportunity to position himself as the defender of the people against the greed of the nobility.

Louis’ authority grew even more during this period, especially after the death of his favorite, the Duke of Luynes, in 1621. With Luynes gone, Louis was freed from this cumbersome friendship, a vestige of his adolescence. However, the situation remained difficult for Henri IV’s son. Despite some affection for Anne of Austria, Louis had a distant relationship with her. He showed little interest in physical pleasures, likely unsettled by their unremarkable wedding night.

As a result, the king still had no heir, leaving the door open to various conspiracies. Meanwhile, the Protestants had risen in rebellion, supported by high-ranking aristocrats and foreign powers, notably England. Given this domestic unrest, the king could not take advantage of the Thirty Years’ War that had broken out within the Holy Roman Empire. His efforts were hampered by the hesitant leadership of his key ministers, whose incompetence paved the way for Cardinal Richelieu, who had patiently positioned himself and developed a coherent political program.

Louis XIII and Richelieu: Absolutism in Action

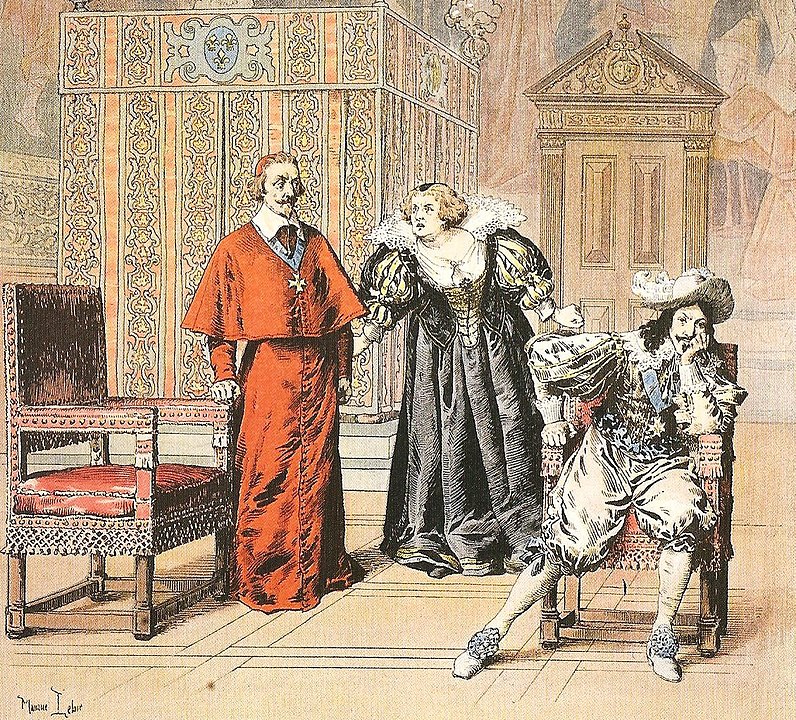

Cardinal Richelieu joined Louis XIII’s council in April 1624. Like the king, he advocated firmness towards both the nobility and the Protestants. Both men shared a vision of a regenerated Catholicism, shaped by the Counter-Reformation, characterized by deep spirituality and aligned with strong royal authority.

Jealous of their kingdom’s independence, the king and cardinal believed they should not be overly dependent on Rome and aimed to rival the Habsburgs. In this respect, they followed in the footsteps of the last Valois monarchs and Henri IV. Realizing this agenda would not be without challenges. The internal war against the Protestants was fueled by both the rebellion of certain nobles and the support they received from England. It wasn’t until 1628 that the citadel of La Rochelle surrendered.

The resulting peace treaty (the Peace of Alès in 1629), while confirming freedom of worship, abolished Protestant strongholds, a legacy of the Wars of Religion. This marked the first step in dismantling the Edict of Nantes, which would gradually lose its substance. It also affirmed royal power, which sought to assert control over military infrastructures.

The Era of Conspiracies

Alongside their struggle against the Protestants, Louis XIII and Richelieu faced numerous noble conspiracies and revolts. At the center of many of these was the king’s younger brother, Gaston d’Orléans, known as “Monsieur,” and the Duchess of Chevreuse. Monsieur took every opportunity to trouble his brother in hopes of advancing his claim as the presumed heir to the throne, as seen in the Chalais conspiracy.

The stunning Duchess of Chevreuse, first married to Luynes and later to a Lorraine duke, managed to turn Anne of Austria against the king. Relations between the royal couple had soured. Louis struggled to show affection for his wife, while Anne opposed his anti-Spanish policies, even leaking military secrets to the Spanish court.

One of the most significant events of Louis XIII’s reign was the famous “Day of the Dupes” on November 10-11, 1630. On this occasion, Marie de Medici tried to turn her son away from Richelieu’s influence. At first, the king seemed to yield to her. Richelieu believed he was condemned to exile, while the queen mother and the nobility savored what they thought was their victory. But in the end, Louis XIII renewed his trust in Richelieu, appointing him as his principal minister and elevating his lands to a duchy-peerage. It was Marie de Medici who was forced to flee, and her supporters were imprisoned.

From 1626 to 1638 (the year of the birth of the heir to the throne, the future Louis XIV), there were at least half a dozen major plots, often leading to armed revolts. These revealed the tense context, driven by the assertion of royal authority. During this twelve-year period, France underwent numerous reforms. The king and cardinal rationalized and strengthened administration, ended certain feudal practices (such as dueling), developed the navy, commerce, and colonies, and oversaw cultural advancements. This period laid the groundwork for the reign of Louis XIV and the emergence of a modern state.

Struggle Against the Habsburgs and the Death of Louis XIII

In governing, the king and cardinal proved to be complementary. Where the king displayed audacity and firmness, the cardinal acted with caution and flexibility. Richelieu excelled at executing the king’s will, giving it the substance and pragmatism needed for success. The two men respected and valued each other, though a certain distance remained between them due to their differing personalities. Nevertheless, their partnership was a success, as demonstrated by France’s resurgence on the European stage. A warrior king, Louis XIII could not remain on the sidelines of the conflict ravaging the Holy Roman Empire. The Thirty Years’ War offered France an opportunity to weaken the Habsburgs that encircled it. Initially, France merely supported the enemies of Vienna and Madrid, particularly Sweden.

In 1635, this “cold war” ended when France declared war on Spain. It was a cruel and costly conflict. Due to their holdings in Franche-Comté, Milan, and the Netherlands (modern Belgium and part of northern France), the Spanish were able to strike at all French borders. Habsburg troops could rely on numerous allies and betrayals. The early years were tough for French forces. The king, commanding in person, did not spare himself and worsened his already fragile health.

It was during this difficult time that Louis became a father. The birth of Louis Dieudonné (a revealing name) was seen as a miracle. In a great act of piety, so characteristic of his fervent faith, Louis even consecrated his kingdom to the Virgin Mary. The following years saw the tide of the war turn in France’s favor, but neither Richelieu nor the king would live to see its end. Armand du Plessis died in December 1642, having ensured his succession through another cardinal: Mazarin. As for Louis XIII, exhausted by war and overwhelmed by illness, he died on May 14, 1643, exactly 33 years after the death of his father.

The Reign of Louis XIII: What is the Legacy?

France in 1643 is heavily burdened by the king’s ambitious policies. The countryside, the cities, commerce, and productive activities have all suffered from continuous wars and revolts. The tax system struggles to bear the military expenses as well as those of an administration that is still in its infancy. And yet, France in 1643 is on the verge of becoming the leading European power of the Grand Siècle. The kingdom has managed to preserve its independence against the Habsburgs and even break free from the encirclement they had imposed. Spain and Austria are exhausted, in decline… Strategic territories (Artois, Roussillon, part of Alsace) have been conquered by French troops.

Domestically, royal authority has progressively asserted itself against the nobles, the Protestants, and various troublemakers. The kingdom’s unity has never been so strong. Key infrastructures and administrative systems crucial for development have been reinforced. Ultimately, a modern monarchical state emerges under Louis XIII. It is true that this king, with his somber appearance, few words, and brooding nature, never garnered the affection his father did, nor did he shine as much as his son Louis XIV. Yet, he was the last French king to be mourned by his people, who considered him worthy of his title: “the Just.”