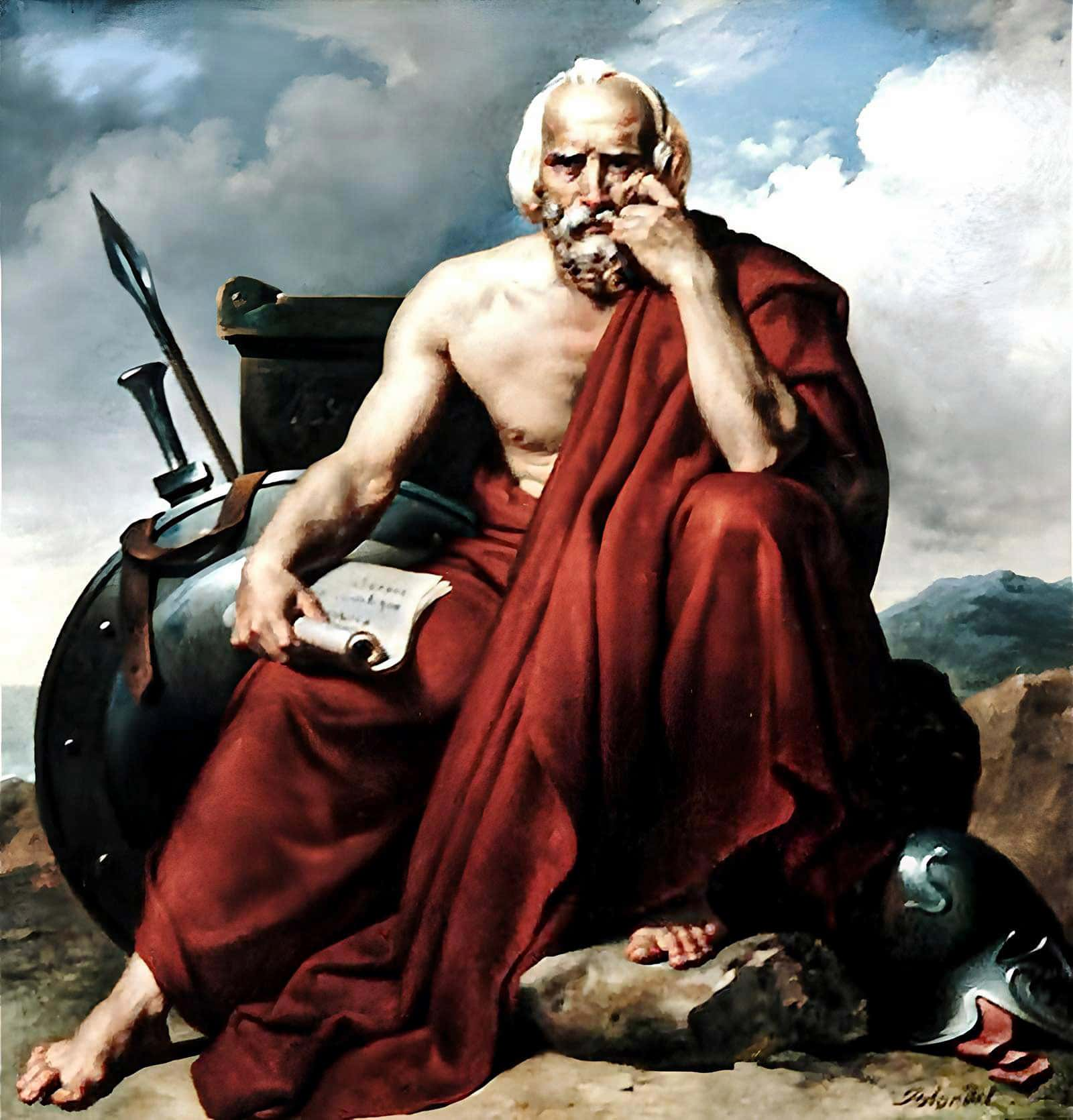

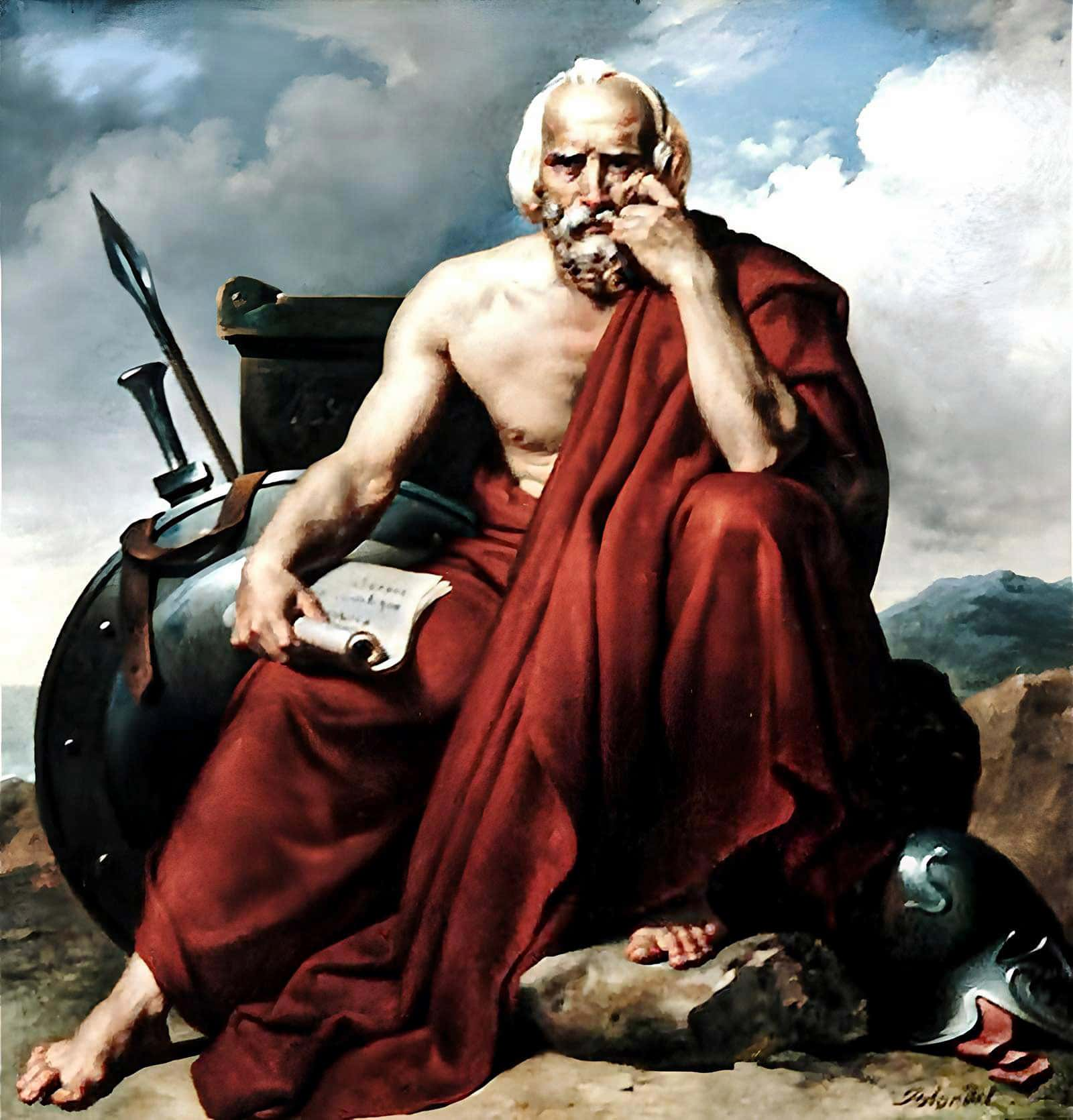

Lycurgus: The Lawgiver of Sparta

Lycurgus implemented political transformations. Even ancient authors lacked precise information about Lycurgus and his activities.

Lycurgus implemented political transformations. Even ancient authors lacked precise information about Lycurgus and his activities.