In Greek mythology, Macaria (from ancient Greek Μακαρία, meaning “the blessed”) is the name of two female characters who are also connected in Greek religion. Although both characters are usually considered separate entities, in the Suda, a Byzantine encyclopedia, they are referred to collectively under the same entry, and Zenobius also closely associates them.

Daughter of Hades

The little that is known about this Macaria, a dark deity of secondary nature, comes from the Suda:

Macaria (“blessed”): Death. A daughter of Hades. Also, a proverb: “to go with the blessed,” instead of departing with sorrow towards absolute annihilation. Or “to go with the blessed,” understood as an euphemism. Since then, the deceased are called “the blessed.”

“Suda” Encyclopedia entry “Macaria”

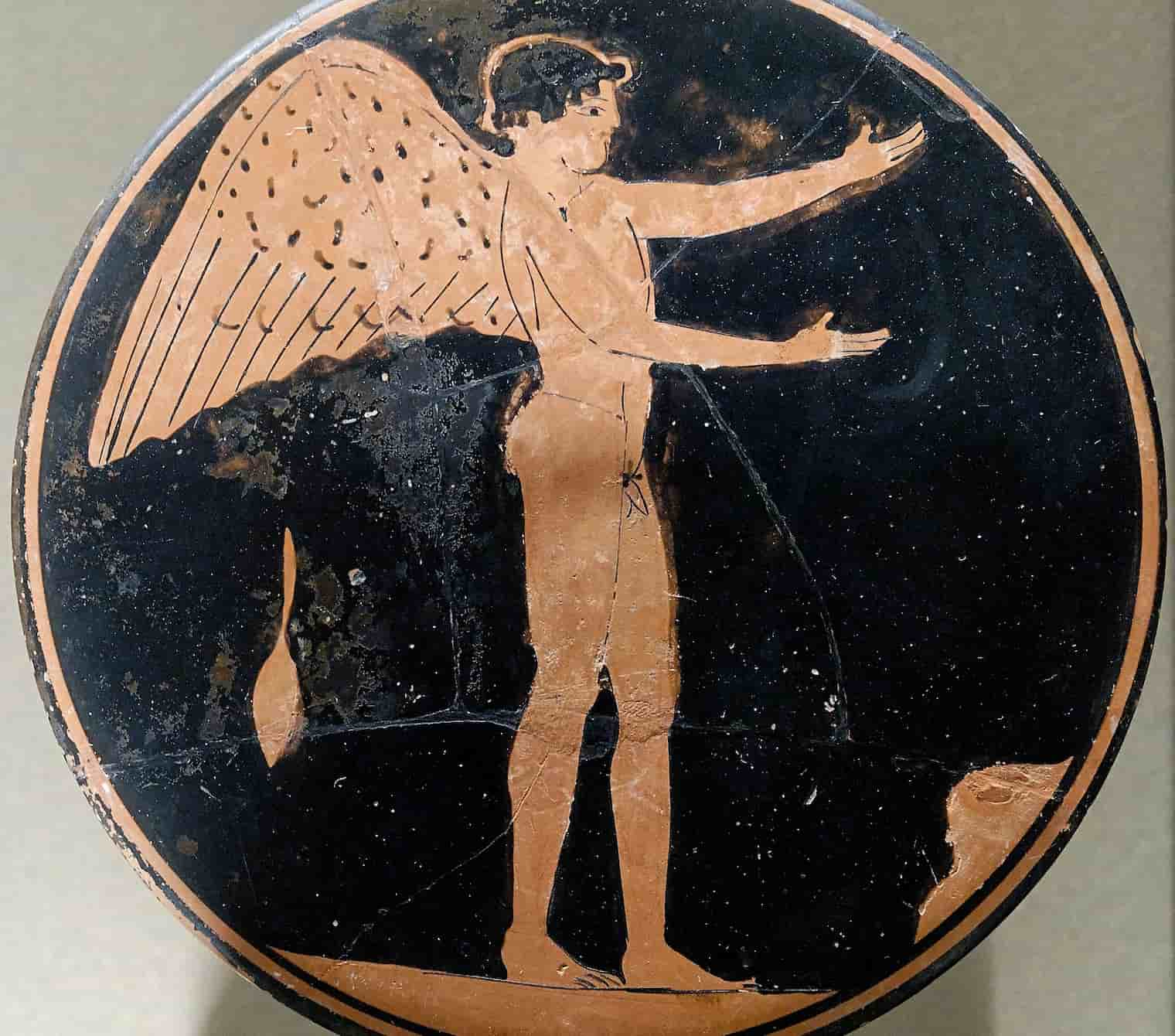

Any additional information about this character falls within the realm of conjecture and interpretation. Her affiliation with Hades as the god overseeing the world of the dead is a logical association, but no source mentions her mother, not even Persephone, as might be expected. In fact, no source in the mythological corpus speaks of any offspring between Hades and Persephone. It has also been suggested that Macaria could be the counterpart of the god Thanatos, understood as the personification of non-violent or sweet death, perhaps as a metaphorical association.

In some myths, she is referred to as his wife, indicating a balance between violent and peaceful death. The text also suggests her connection to the Isles of the Blessed, where the souls of the virtuous pass. She appears to have been a representation of “blessed death” since her name referred to “the blessed dead,” a euphemism used to name those who had died heroically.

Daughter of Heracles

Described in Euripides’ “Heracleidae,” Macaria is the only daughter of Heracles, born to Deianira, if we overlook Mirto, Patroclus’ sister, who had Euboea with Heracles (possibly the same character as Macaria). Even after Heracles’ death, Eurystheus sought revenge by killing all the hero’s children, the Heracleidae.

Macaria had no choice but to flee with her brothers and Iolaus, first to Trachis, where asylum was denied, and later to Athens. There, they were welcomed by the hospitality of Demophon, a son of Theseus who then ruled the city. When they arrived at the gates of Athens with their army, Eurystheus gave Demophon an ultimatum, threatening war against Athens unless Demophon handed over all the Heracleidae.

With commendable resolve, Demophon refused to negotiate with Eurystheus and prepared for war. It was then that an oracle predicted that Athens would only emerge victorious if a maiden of noble blood was sacrificed in honor of Persephone. Upon hearing this, Macaria understood that her only option was to die voluntarily on the altar or accept a death imposed by Eurystheus.

Since she would never be granted a normal and happy life, she had no choice but to offer herself as a victim to save the city and its inhabitants. Full of courage, she rejected the lottery that involved other girls and offered herself at the altar.

This was the heroic end of Heracles’ daughter. Later, the Athenians honored her with lavish funerary rites, but above all, the myth has a clear eponymous aspect: the spring where Macaria lost her life, near Marathon, has borne her name ever since.

Macaria and Thanatos

Thanatos supposedly fell in love with Macaria as he escorted her to the underworld, and they allegedly had a secret relationship, as no mortal could be bound to a living being, whether human or god. Their union supposedly resulted in the birth of Lyncos. However, Hades eventually discovered their relationship, separating them and banishing Lyncos, who then went into exile near the Black Sea and lived among the Scythians.

References

Macaria is primarily mentioned in Euripides’ “The Heracleidae,” where her story and self-sacrifice form the subject of the play. Pausanias recounts the same myth when mentioning the Macaria fountain in Marathon.