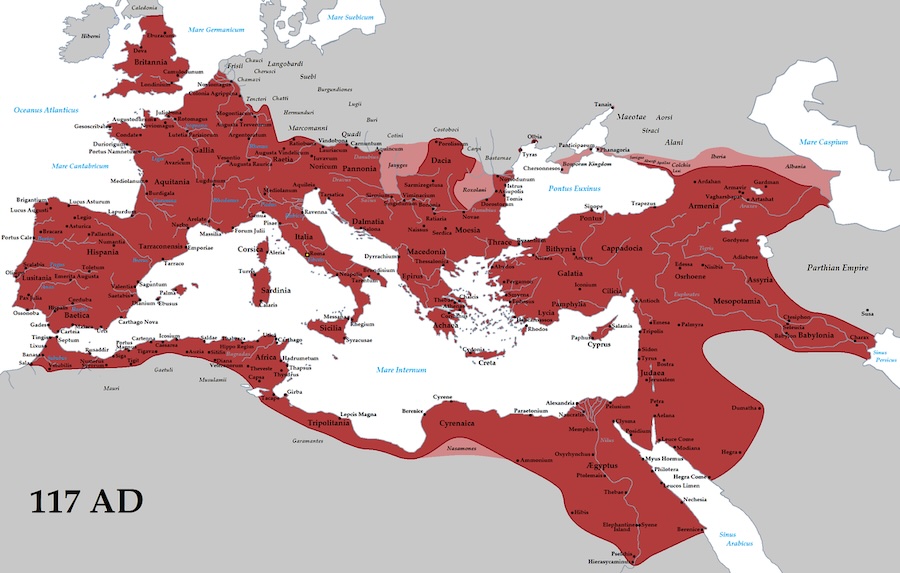

The Mediterranean has been at the heart of Roman history since the founding of Rome, and even more so as its imperialism developed. This allowed it to control the entire Mediterranean region within a few centuries, leading to what is commonly called “Mare Nostrum,” although the term is not widely used in Latin sources and has more of a political rather than geographical meaning.

However, as early as the 2nd century AD, under the reign of Marcus Aurelius, the Roman Empire’s center of gravity seemed to shift more towards the north. Did this change the relationship between Rome and the Mediterranean, and how did it evolve until the reign of Constantine?

Later Use of “Mare Nostrum”

The term was revived by Benito Mussolini in the early 20th century as part of his vision of restoring Italy’s ancient imperial glory. Mussolini sought to re-establish Italian dominance in the Mediterranean, using the phrase to invoke the memory of the Roman Empire. His regime pursued expansionist policies in the Mediterranean, including the occupation of Libya, Ethiopia, and Albania, though these ambitions ultimately failed during World War II.

A Mediterranean Still Vital to Rome?

Rome was less and less occupied by power, but the Mediterranean itself seemed to be less central to Roman concerns, with a few exceptions (such as the East). This was mainly due to the barbarian threats along the borders of Gaul, the Rhine, and the Danube. However, it would be wrong to say that the Mediterranean lost its importance in Rome’s functioning and life; it remained vital!

At the beginning of the 3rd century, it still concentrated the majority of Roman trade, and especially the supply of essential goods to the heart (despite the emperors’ increasing distance) of the Empire. Rome depended entirely on the transport of essential foodstuffs (such as wheat) via the Mediterranean. Did this situation evolve later, particularly during the crisis of the 3rd century and under Constantine’s reign?

Let us first describe the geographical situation of the Mediterranean. The Mediterranean is not a sea, but a succession of liquid plains communicating with each other through more or less wide gates. The Mediterranean space is thus, above all, varied, in terms of terrain but also climate depending on the regions. The presence of numerous peninsulas also explains the complexity and irregularity of winds and currents.

This variety partly explains why the Romans, far from feeling a sense of “unity” that one might find in the concept of Mare Nostrum, referred to the Mediterranean with local criteria, speaking of the Mare inferum (Tyrrhenian), superum (Adriatic), Africum, etc.

In terms of geography, the seasons are more or less favorable for navigation: according to sailors of antiquity, the Mediterranean only had two seasons, one good and one bad, but this distinction depended on the regions. Winter was thus the bad season when the Romans used the term mare clausum (closed sea), at best engaging in coastal navigation and certainly not in deep-sea voyages or large commercial expeditions.

The good season began in March with the festival of Navigium Isidis and lasted until November 11, for the most optimistic, though this period was not without risks. Since voyages were intra-Mediterranean, sailors had to face the variety of winds and currents, and the alternation between calm and rough seas, depending on the regions, as mentioned earlier.

Roman Navigation in the Mediterranean

We are particularly interested in the ships (commercial, with military ships discussed later) and the maritime routes, distances traveled, etc. According to M. Reddé, there were “symmetric” and “asymmetric” hulls, but most appeared to be round (thus rather symmetric), and ships with shallow drafts often had to be ballasted in case of strong winds. The sails were usually square or rectangular, with ships featuring up to three masts by the 3rd century.

Steering was mainly done with two large oars fixed to either side of the stern. The most important aspect of commercial ships was, of course, their tonnage, or carrying capacity: under the Empire, most ships carried around 450 metric tons, but it became increasingly common to see ships reaching 1,000 tons or more.

Regarding navigation itself, sailors primarily relied on the wind, which determined their routes in the Mediterranean. Moreover, they navigated mostly by “dead reckoning” (despite knowledge of the stars or currents) in deep waters, which could lead to voyages of varying lengths. On the other hand, when close to the coast, sailors relied on “Peripli” (ancient travel itineraries) that listed water sources, reefs, dangers, or possible shelters. In any case, shorter routes often allowed for avoiding piracy (which will be addressed in the third part).

All maritime routes (like the land routes) led to Rome, specifically its ports: Puteoli, followed by Ostia and Portus (independent from Ostia in 313). Starting from the East, the most frequented routes went from Egypt to Italy, passing either through Crete or Africa; also in the East, there was a route from the northern Aegean Sea to Corinth and the port of Lechaeum via the isthmus, as well as one from Syria to Italy via Cyprus or Crete.

In the western Mediterranean, routes passed through major ports like Carthage, Cartagena, Arles, Marseille, to reach Ostia, from which routes also connected to the islands of Sardinia, Sicily, and Corsica. M. Reddé uses specific examples to study these routes, such as records like the “Stadiasmus of the Great Sea,” of uncertain origin, and especially the “Antonine Itinerary” from the 3rd century AD, which provides information on the maritime routes between Rome and Arles, illustrating coastal navigation, the most common practice.

The duration of voyages, as we have seen, depended greatly on navigation conditions. It appears, for example, that it took between 15 and 20 days to travel from Alexandria to Puteoli, 20 days from Narbonne to Alexandria, and 2 days from Africa to Ostia. These are relatively short journeys, likely one of the factors in the intensity of exchanges in the Mediterranean.

Ports were, of course, the nerve centers of maritime trade. They were generally of two types: the older ones were often located outside cities (Ostia for Rome, for example), while the newer ones were within the cities themselves (such as Alexandria). All were developed, with enclosed harbors and buildings for commerce; thus, what was called a macellum in Ostia or Puteoli, or an agora in the East, were sorts of local markets intended to distribute goods brought by maritime trade, which then spread throughout the rest of the Empire.

While we won’t discuss all the ports, we can mention Ostia, Rome’s major port, still vital during the period we are studying, up until 313 when it specialized in the annona (grain supply), which we will return to. It was primarily developed under Claudius (41-54 AD) and expanded under Trajan (98-117 AD); its basin could accommodate 200 ships and was connected to the Tiber River. It gradually replaced Puteoli, particularly from the 2nd century AD onwards. Besides Ostia, the other major ports were mainly Alexandria and Carthage, due to their roles in shipping wheat to Rome, and later to Constantinople from the 4th century onwards.

The concept of Mare Nostrum is a general one that does not exactly reflect the reality of the time, especially in terms of geography, but it provides a fairly accurate idea of Roman mastery of the Mediterranean. The Romans knew how to control it, thanks to a substantial fleet (though this varied over time) and a network of important ports, all supported by knowledge of routes that dated back to before the Empire. But this control had a purpose: commerce and, above all, the supply of Rome. It was not absolute, however, and was subjected to various pressures, particularly as barbarian threats became more pressing, leading to the involvement of the Roman war fleet.

Products and Trade in the Mediterranean

What is the nature of the exchanges and goods circulating in Roman Mediterranean trade, how is commerce regulated, and what is the importance of the annona for the life of the Empire?

The products that move along the trade routes we have described include wine, for example, which mainly comes from Catalonia, Gaul, but also Rhodes and even Asia Minor. It is also obviously present in Italy (mainly in Campania). Spain exports garum (fish sauces), olive oil comes from Baetica or Africa, wheat from Egypt (or also from Africa), and textiles from Syria. Precious goods often transit through Alexandria or even Carthage; these are silk, ivory, pearls, etc., and in the 3rd century, they could come from India via the Red Sea. Similarly, there were exchanges with the Persians and the Chinese through the ports of Syria. Finally, from distant Africa came wild animals for venationes (public spectacles of wild animal hunts), slaves, and ivory.

Let’s focus, however, on key products of commerce during this period, knowing that their quantity and quality often account for the wealth and importance of the provinces from which they originate. First, wine: present in Italy, the finest wines are produced primarily in Campania; vineyards can also be found in the western provinces up to southern Gaul, and even in Africa.

In the wine trade, while the Italians were able to export and benefit during the early days of the Empire, they gradually lost their advantage to the wines of Hispania and Gaul, with provincial wines soon representing the bulk of trade, even though Italian wine continued to be exported along the Danube, and the finest wines still came from the peninsula.

Olive oil, on the other hand, mainly concerns Baetica and Africa and is linked to the services of the annona (which we will address later); it is exported not only to Rome where it is stored but throughout the West, reaching as far as Britain and Germany. There is also olive oil production in Syria, but it is less well-known, and it is unclear whether it was exported like the oil from Baetica and Africa. Olive oil is a product regularly distributed starting with the reign of Aurelian, on a daily basis.

Finally, wheat is the most important commodity, and through it, we can discuss the annona: wheat is brought to Italy from Egypt and Africa, but also from southern Gaul, Sicily, and Spain. Egypt had to prevent famine in Rome by providing enough to last four months, equivalent to 20 million modii (172 million liters). The transport arrived at Portus starting in 313, between March 1st and November 15th, through the navicularii, who deserve further attention: they were private traders responsible for the annona, as it should be noted that Rome did not have a “state” merchant fleet.

The navicularii were often families (such as the Fadii of Narbonne), owning their own ships, and they were organized into collegia or corpora; Jean Rougé referred to them as “capitalist societies.” They transported annona provisions at the emperor’s request in exchange for privileges (such as using the ships for their private activities), benefiting all parties involved.

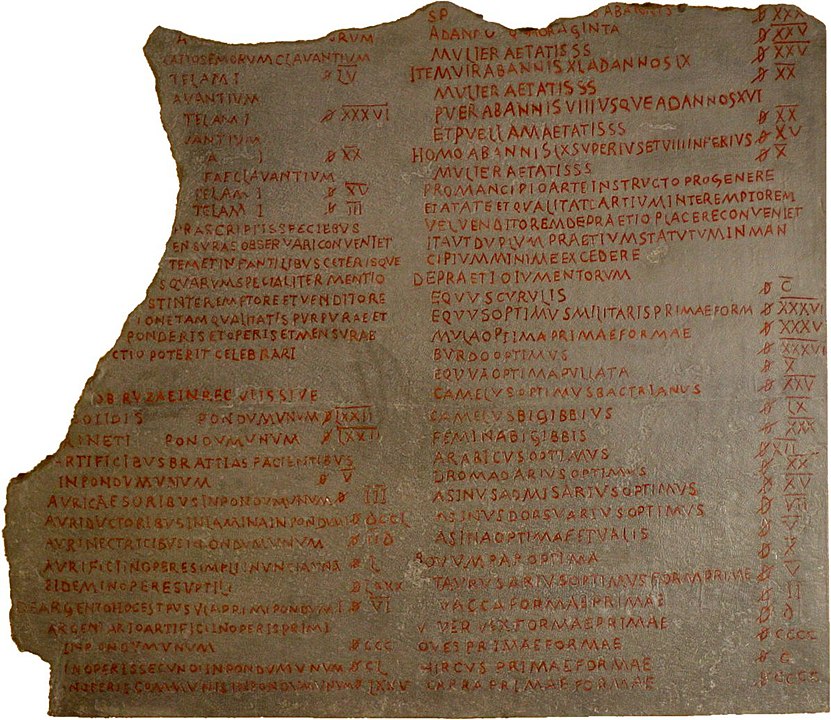

Commerce itself, relatively free before the 3rd century, became increasingly controlled and regulated as the 4th century approached: the Edict of Maximum Prices in 301 provided the price for transporting goods: 16 denarii per military bushel between Alexandria and Rome, 4 from Africa to Nicomedia, 20 from Syria to Spain. According to the “Expositio Totius Mundi” (an anonymous 4th-century source), trade was flourishing in the Empire, especially in the eastern Mediterranean, while in the West it seemed to be slowing down, despite the growth of the port of Arles.

The Annona

This service was created by Augustus but was more relevant than ever to Rome during our period, even though it underwent modifications. Its mission was to supply Rome with wheat, to prevent famines that had regularly affected the city in the past. A prefect of the annona, of equestrian rank, was in charge. In a career path, one could be a prefect of the annona before becoming a prefect of Egypt or the Praetorian Prefecture, highlighting the importance of this role. According to Pavis d’Escurac, the prefect of the annona was responsible for “gathering, transporting, and storing the wheat quotas essential for the needs of the entire capital.” Under Aurelian, he had at his disposal the arca frumentaria and arca olearia, funds to help manage these supplies.

From the 3rd century onwards, the annona also included olive oil, and it was managed by a procurator of the annona and a freedman procurator. At the same time, the ports responsible for the annona, mainly Portus and Ostia, were placed under the control of a procurator of both ports. The system was later simplified in the second half of the 3rd century. In the provinces, provincial procurators managed the annona, stationed in specialized granaries like those in Neapolis and Ad Mercurium in Alexandria. With the tetrarchy, a prefect of the African annona also appeared, reporting to the praetorian prefects, while the vicars of dioceses also became responsible for supplying Rome with wheat.

The Organization of the War Fleet

Roman military ships were galleys, partly inspired by the Greeks. They were not round but long and slender, designed to be fast and maneuverable. Unlike merchant ships, they were primarily oar-powered, requiring a large crew and not depending on the wind. However, a drawback of these galleys was their fragility in rough seas, though they were still willing to venture out.

Their main difference from transport ships was, of course, their armament: galleys were equipped with various rams meant to smash the enemy’s hull, sometimes with towers at the front and/or back, and an “artillery” of ballistae that launched either stones or bolts (sometimes flaming). Finally, there were different types of galleys, varying in shape, size, the number of decks, or rowers, such as triremes or polyremes.

These main warships, supported by auxiliary vessels, were stationed in military ports, the principal bases of the Roman fleet, though other “civilian” ports could host them during movements in the Mediterranean. The main military ports were those of Ravenna and Misenum, tasked with protecting the Italian peninsula with the fleets known as classis praetoriae.

They were founded by Augustus, with Misenum in particular noted by Tacitus and Suetonius, while Ravenna may have been used as a military port before Augustus’ reign. According to Dio Cassius, Ravenna could accommodate 250 ships, though it was unclear if they were all warships, as the port might not have been solely for military use. As for Misenum, its installation may date to 12 BCE, but its fleets were transferred to Constantinople in 330.

The Roman fleet had numerous and varied missions, although for a long time, escorting merchant fleets did not seem to be a priority, for example. The Pax Romana led the fleet, for several centuries, to mainly carry out “police” missions rather than strictly military ones, as Rome completely controlled its maritime domain and had no enemy capable of raising a significant fleet. It thus served as support to the land army, primarily handling its supply.

So, what could its other missions have been? Concerning commerce and its control, can it be said that the military navy played a role, particularly with the annona? There were military personnel at the service of the annona, though they were rare, such as the cornicularius procuratoris annonae in Ostia; however, they were probably only assigned to the role, not sailors.

Coastline defense might have involved the Roman navy; under the principate, the post of praefectus orae maritimae was created, reserved for knights, but the magistrate apparently did not have a fleet under his command. Therefore, these were not missions that can be attributed to the Roman navy. However, the navy was useful in times of peace for transporting officials and acting as an escort during troubled and less secure periods, such as the one under discussion.

As we see, it is quite difficult to define the missions and therefore the usefulness of the Roman navy, especially in peacetime. This seems to have weakened it, while threats became more pressing in the Mediterranean itself by the 3rd century. Did the Roman navy then react, and if so, how? During this period, the fleet continued to be administered and “centralized” in the ports of Ravenna and Misenum (each with a prefect) despite the difficulties. For instance, M. Cornelius Octavianus, according to epigraphic sources, commanded the fleet of Misenum in 258–260. Therefore, the Roman navy did not disappear during the 3rd-century crisis, and it had to respond to the threats.

The Navy in the Face of Threats

Until the reign of Valerian, the military navy was active, primarily in supporting ground troops and providing supplies. However, the death of Trajan Decius in 251, on the Danube, marked a turning point as this river became the route through which barbarians threatened the Mediterranean, leading to the navy’s involvement in this region, where it was weakest. In 267, the Pontic fleet had to retreat before the Goths, who then poured into the Aegean Sea and the eastern Mediterranean, even threatening Egypt! The prefect of the province faced them off the coast of Cyprus in 270.

Under the reign of Probus, another episode demonstrated that the navy no longer controlled Mare Nostrum: the Franks, departing from the Pontus, stole ships and managed to cross the straits to pillage Sicily and Italy! They pushed as far as Gibraltar without ever confronting a Roman fleet. Piracy, in turn, resurged, as confirmed by a text from Ammianus Marcellinus (4th century); the Cilicians were specialists in this, but this mainly reflected Rome’s loss of control over certain populations.

However, the situation was not entirely grim for the Roman navy: aside from the Frankish raid, most of its difficulties occurred in the eastern Mediterranean, with the West, and therefore Rome, being relatively spared. It was thus more a breakdown of the naval defense system rather than the entire navy. Later, with Diocletian’s reforms (which affected, among others, the military and the navy), an evolution took place.

According to a source from Justinian’s time, the Roman navy had a personnel count of 45,562 men during the Tetrarchy. However, the Constantinian period witnessed a real transformation of the Roman navy in the Mediterranean: Constantine used the navy for his reconquest of Italy in 312, while his rival Maxentius had used it for Africa in 310-311. The Roman navy was therefore divided along the same lines as the Empire. Constantine’s victory caused the fleets of Ravenna and Misenum to lose their title of praetoria, as they were purged for supporting Maxentius.

Constantine reorganized the fleet and transferred its key bases to Greece, and later to Constantinople, his new capital. This period thus saw a shift in the fleet’s operations after the barbarian threats and the civil wars that followed the Tetrarchy. New squadrons were created, a balance was struck in favor of the East and Constantinople, leading to a more scattered and less massive navy, focused on defense and possibly better equipped to face new barbarian threats like those of the late 3rd century.

The Mediterranean, therefore, remained central to the Empire’s life, despite the shift of its center of gravity northwards due to invasions and the emperor’s distance from Rome. The Mediterranean continued to serve as Rome’s main commercial zone during this period, with the annona (grain supply) remaining just as important. The changes mainly affected certain sectors like the management of the annona, increased control over commerce following the Edict of 301 (despite the preservation of the navicularii), and especially the Roman navy, which, after failing to respond to barbarian invasions, proving it was no longer capable of ensuring full “Romanness” of the Mare Nostrum, had to reform under the Tetrarchy and Constantine.

This period, therefore, was primarily one of transition and adaptation for Rome concerning its maritime space, possibly signaling the beginning of the end of Mare Nostrum.