Margaret of Valois (1553-1615), known as Queen Margot, Queen of France and Navarre, was the daughter of King Henry II and Catherine de’ Medici, and the sister of Charles IX and Henry III. On August 18, 1572, she married the leader of the Huguenots, Henry of Navarre (the future Henry IV), symbolizing an attempt at reconciliation between Protestants and Catholics.

Too often used as a “pawn” by her mother during the French Wars of Religion of the 16th century, she received many funeral tributes at her death in 1615: “the Queen of grandeur, the grandeur of spirits, the noble of flowers, the Margaret of Valois.”

The Youth of Margaret of Valois

Margaret of Valois was born in May 1553 at the Château de Saint-Germain, frail and thin. Of her five brothers and two sisters, the future Charles IX nicknamed her Margot. She spoke early and received a princess’s education in Amboise: literature, dance, and music. Raised under the fear of her mother, she was only six years old when her father, Henry II, died. She already showed a strong temperament and refused to change her religion despite pressure from certain members of her entourage.

Talk of alliances soon began… Jeanne d’Albret wanted Margaret for her son, the King of Portugal for his young Sebastian, the King of Spain for Don Carlos, and Philip II of Spain for himself after the death of his third wife, Elisabeth of France… Little Margaret played with Henry of Guise!

Falling in love with him, she was watched and denounced, despite her friendship with her brother, Henry of Anjou, to whom she served as a “spy.” Henry of Guise declared his love for her, but a plot was hatched against him, forcing him to leave the court and marry Catherine de Clèves.

A Marriage for the Sake of the State

Efforts on behalf of the Prince of Navarre resumed in August 1571, but Jeanne d’Albret was hesitant… For her, the French court was nothing but artifice, corruption, and resembled Hell. Eventually, she met Charles IX and Catherine de’ Medici, who won her over (the king sought revenge on his enemies and thus granted his sister’s hand to a Huguenot). The contract was signed on April 11, 1572, despite the absence of papal dispensation and the sudden death of Jeanne d’Albret in June. On July 20, the King of Navarre and future Henry IV arrived in Paris with 800 gentlemen, and the wedding took place in August 1572.

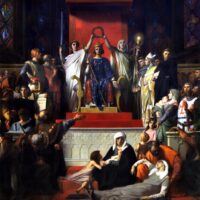

More than 120 ladies displayed their finest velvet attire adorned with gold and silver. The two processions were surprising: on one side, the king, the queen mother, the princes of the blood, the House of Lorraine; on the other, the King of Navarre, the Prince of Condé, Admiral Coligny, and the Count of La Rochefoucauld. While Margaret listened to the mass, the King of Navarre and his followers strolled in the cloister. He was fetched at the end of the mass for the “I do.” Margaret remained silent, not forgetting her love for Guise, and Charles IX, very angry, pushed her head forward: it was her “Yes.” The feast and festivities lasted three days with delicious food and grand spectacles.

Only the common people were displeased; a political marriage with Protestants was an insult. The Protestants preferred to leave, Coligny was attacked, and La Rochefoucauld was killed!

Queen Margot’s Role

After the St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre, Margaret pleaded for her husband’s cause with François d’Alençon (Francis, Duke of Anjou). Already abandoned by Navarre, they still lived in perfect harmony. For the reception of the Polish ambassador, she performed her role flawlessly, delivering a speech that was applauded, and “everyone called her a second Minerva or goddess of eloquence,” triumphing in the festivities.

As a dutiful daughter of France, she thwarted her brother d’Alençon’s and her husband’s attempted escape. A year later, she foiled the Politicians’ conspiracy led by Montmorency, Turenne, and Cossé, by becoming the mistress of Joseph de Boniface, Lord of La Mole (who belonged to d’Alençon).

However, after the death of King Charles IX, Margaret’s position became difficult. Without her knowing, her brother had been protecting her. When her husband and d’Alençon were imprisoned in Vincennes, as a devoted wife, she thought of helping them escape… but as they argued over who would escape first, she gave up.

She maintained her role during the festivities in Lyon, despite rumors about her affair with Louis de Clermont, seigneur de Bussy, (Bussy d’Amboise). Navarre expelled her only confidante, Mme de Thorigny, and tension between the spouses reached its peak. D’Alençon left the court in September, and Henry of Navarre slipped away in February 1576… Margaret was placed under house arrest, forbidden from leaving the kingdom. She was shunned, despite protests from d’Alençon, Crillon, and even Navarre, who sent an envoy to the king. Her attempt to go to the spa in Spa was uncovered, and she joined d’Alençon, waiting for peace until September 1577.

Thanks to d’Alençon, who escaped from the Louvre in February 1578 and raised an army to go to Flanders (Flanders was under Spanish control!), the queen mother allowed her daughter to depart but accompanied her, with her Flying Squadron, to inspect the Reformed troops. On August 2, Margaret set out with the household that Henry III had graciously assigned her.

At the Court of Nérac

In Bordeaux, Margaret was warmly welcomed, serving as a reconciliator between her husband and Marshal de Biron. At Nérac, she was happy to reclaim her status, her château, her husband, and life resumed pleasantly. She was courted by Viscount de Turenne, while Henry entertained La Rebours (Margaret’s lady-in-waiting) and decided to manage his mistresses by establishing the theory of Neoplatonic love!

“Flirting and love-talk are permitted, but deflowering is forbidden!”

Everything worked until Navarre learned of Margaret’s relationship with Turenne. Unyielding, the “war of lovers” was declared at the end of 1579: it was a matter of seizing towns belonging to one or the other, unbeknownst to either party—such was the case for Cahors! There was talk of a rupture, though Margaret was present during the king’s 17-day illness and even helped the king’s mistress, Belle Fosseuse, give birth to a stillborn daughter.

Margaret grew bored at this court, which was incomparable to the Louvre, despite the intrigues and rumors, until the arrival of Jacques du Harlay, Lord of Champvallon, a friend of d’Alençon. Handsome and literate, he had all the qualities to win her heart, and he spoke of love. She quickly forgot Bussy, dismissed Pibrac, and loved Champvallon, whom she reunited with in Paris in early 1582 when Henry III summoned her to quell the rebellion. All of the Louvre was aware of Navarre’s child with Belle Fosseuse, who was dismissed. Navarre was furious, and Margaret reproached him, supported, for once, by her mother.

Too beautiful and too intelligent, Henry III could no longer tolerate his sister and expelled her during a ball on August 7, 1583. Without money or support, she headed for Nérac, but Navarre stopped her at Cognac, preoccupied with Corisande until April 1584, when he agreed to take her back. The reception was frosty; she was marginalized and humiliated. As queen, she nonetheless received d’Epernon, who was to convert the king to Catholicism. But Navarre made her life difficult: he had her secretary abducted, threatening him with torture, though he was merely a messenger between Catherine de’ Medici and her daughter.

In March 1585, feeling unsafe, Margaret went to Agen for her devotions, locked herself in the castle, and nearly raised an entire army at her command. Civil war was launched. She sought help from Henry of Guise to repel the heretics. Unfortunately, Marshal de Matignon recaptured Agen, forcing Margaret to flee.

Margaret: Queen of Usson

Having only part of her escort left, Margaret headed towards Carlat, where she was met with hostility. Harassed on all sides, she tried to raise troops in Gascony. Abandoned by both Henry III and Henry of Navarre, she turned to her mother, who offered her shelter at the Château of Ybois, near Issoire, in the autumn of 1586. But it was a trap: Canillac, following the orders of the king, seized Margaret and imprisoned her in the Château of Usson.

Rumors were already circulating: “The Queen of Navarre is very ill. She is suffering from general pains and is in such a state that only a sad outcome is expected.” Margaret realized that the Valois family had effectively cast her out. She wrote to her mother, asking her to take care of her guards and ladies-in-waiting, to pay and relocate them in case of her demise. By the end of the year, her mother and brother had calmed down and forced Navarre to take care of his wife.

Reassured about her life, Margaret began thinking only of revenge. Master of her castle, she organized resistance against the royal power, with Usson becoming the headquarters for the leaders of the League. She began writing her Memoirs, which she dedicated to Brantôme, and met with Saint Vidal (leader of Velay), the Count of Randan (commander of Auvergne), and Urfé (the famous author of L’Astrée).

The shock of her brother’s death brought her closer to her husband. Encouraged by Gabrielle d’Estrées, Navarre asked her for the annulment of their marriage. Margaret agreed, on the condition that she would retain all her acquired privileges and receive money to pay off her debts. The negotiations lasted over five years. In exchange for her assistance in the trial against Henriette d’Entragues, she requested her share of the inheritance and dedicated it to the Dauphin Louis. With Gabrielle’s passing, Margaret reappeared on October 21, 1599, ready to do everything necessary to facilitate and accelerate the dissolution of her marriage, with one goal: to leave Usson.

Everything moved quickly. On November 10, the marriage was declared null. She retained her title as queen and duchess of Valois, her lands, and received 200,000 écus payable over four years. Henry IV and Marie de Medici married in December 1600, and on September 27, 1601, Louis XIII was born.

Return of Queen Margot to Paris

Finally, having received permission to return, on July 18, 1605, she crossed Paris, escorted by the young Duke of Vendôme. On the 26th, Henry IV visited her at the Château de Madrid, and the next day, it was Marie de Medici. Margaret was welcomed at the Louvre and cheered by the people. On August 6, the Dauphin awaited her on the road to Saint Germain. Enamored with the young boy, Margaret bequeathed all her possessions to him and gifted him a Cupid studded with diamonds, seated on a dolphin adorned with an emerald, and a small scimitar encrusted with jewels.

Often afflicted with illness and dysentery, Margaret had lost her beauty, become horrendously overweight, and dressed as an old woman, wearing wigs made from blonde hair borrowed from her servants. In April 1606, she lost her young and beloved squire Dat de Saint Julien, whom she passionately adored, and she moved to Pré aux Clercs as the plague approached Paris. In September, she bought a house in Issy from Jean de la Haye, the king’s goldsmith, and began beautifying it, decorating the park with statues and painting murals on the walls. She regularly hosted the Dauphin, who received a jewel-encrusted cord worth 3,000 écus from her in 1609.

Back in Paris in October, she was overjoyed to reunite with her squire Bajaumont, now a philosopher and valiant soldier, whom she would lose at the end of 1609 when he was attacked in a church. Her salons were filled with diplomats, soldiers, and poets. She hosted receptions attended by the king and queen, where they discussed various topics and indulged in everything. Henry IV himself remarked on returning from her “brothel.” Upon the king’s death, she had a solemn service sung with two funeral orations. Remaining on good terms with the queen, she played a role in the Franco-English alliance for the marriage of Henriette, but she lived apart from the court.

Final Years of Margaret of Valois

Towards the end of 1614, Margaret of Valois fell ill with liver congestion, complicated by kidney stones. Her chaplain, judging her condition serious, warned her. On March 7, 1615, she laid the first stone of her tomb. Queen Margot passed away on March 28, 1615, at the age of 62, leaving 100,000 livres to the poor and 200,000 écus in debts, which were paid by Marie de Medici. A year later, her body was transported from the convent of the Daughters of the Sacred Heart to Saint Denis.

The end of her 1615 funeral oration cannot be forgotten: “Margaret of France is dead! Farewell to the delights of France, the paradise of courtly pleasures! The brilliance of our days, the day of beauties, the beauty of virtues, the elegance of lilies, the lily of princesses, the princess of greatness, the queen of majesty, the grandeur of minds, the spirit of wisdom, the prudence of nobles, the noblest of flowers, the flower of Margaret, Margaret of France.” A far cry from the dark legend of the queen that history would leave to posterity.