Maximilien Robespierre: Architect of the Reign of Terror

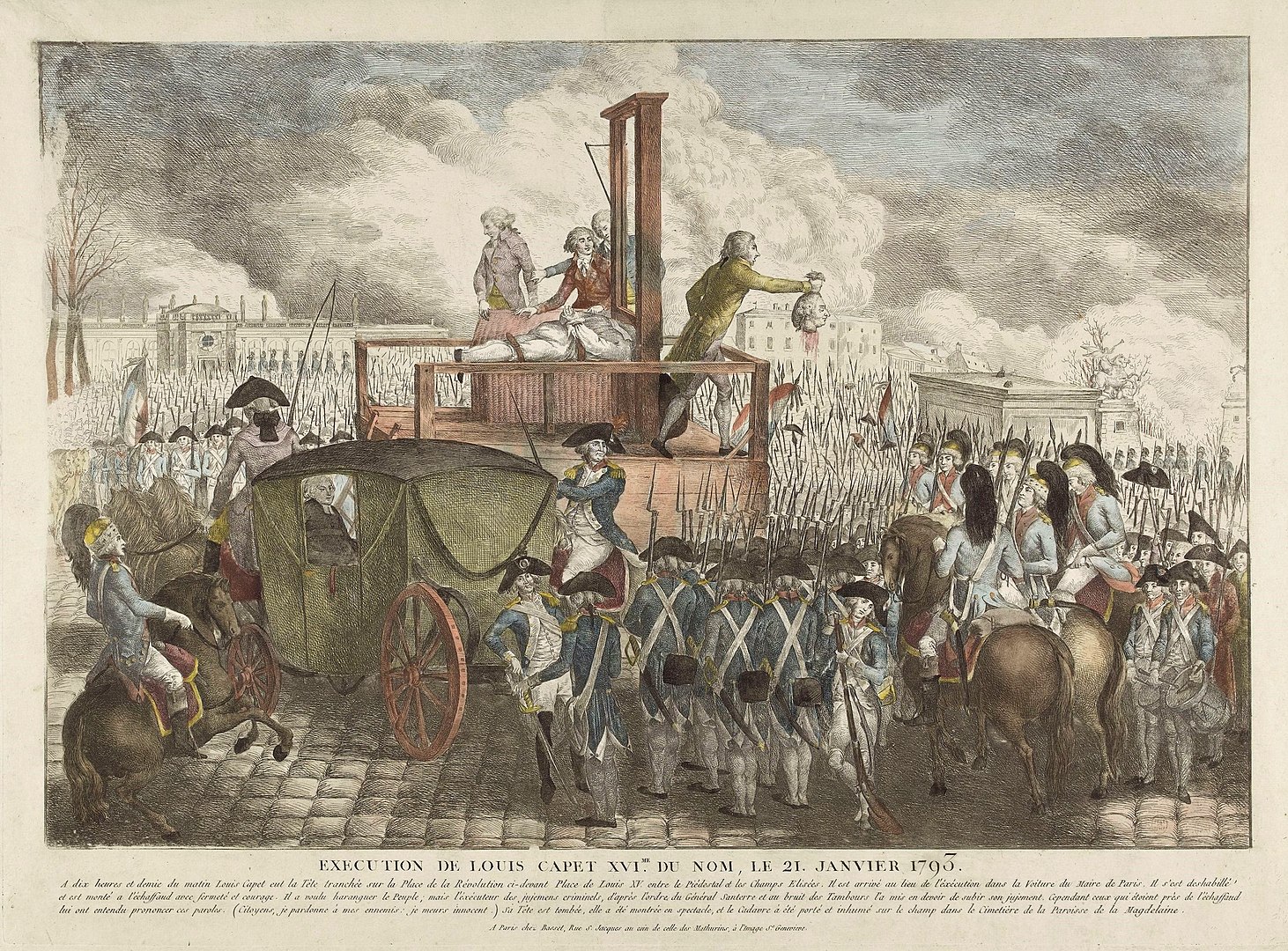

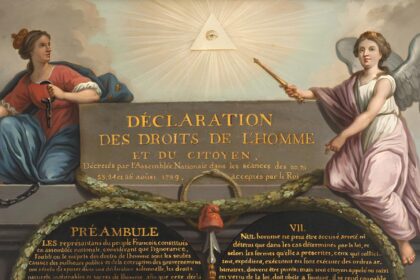

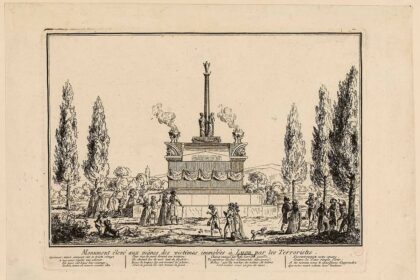

Maximilien Robespierre was a prominent figure during the French Revolution and a key leader of the radical Jacobin faction. He played a significant role in the Reign of Terror, a period of intense political upheaval characterized by mass executions.