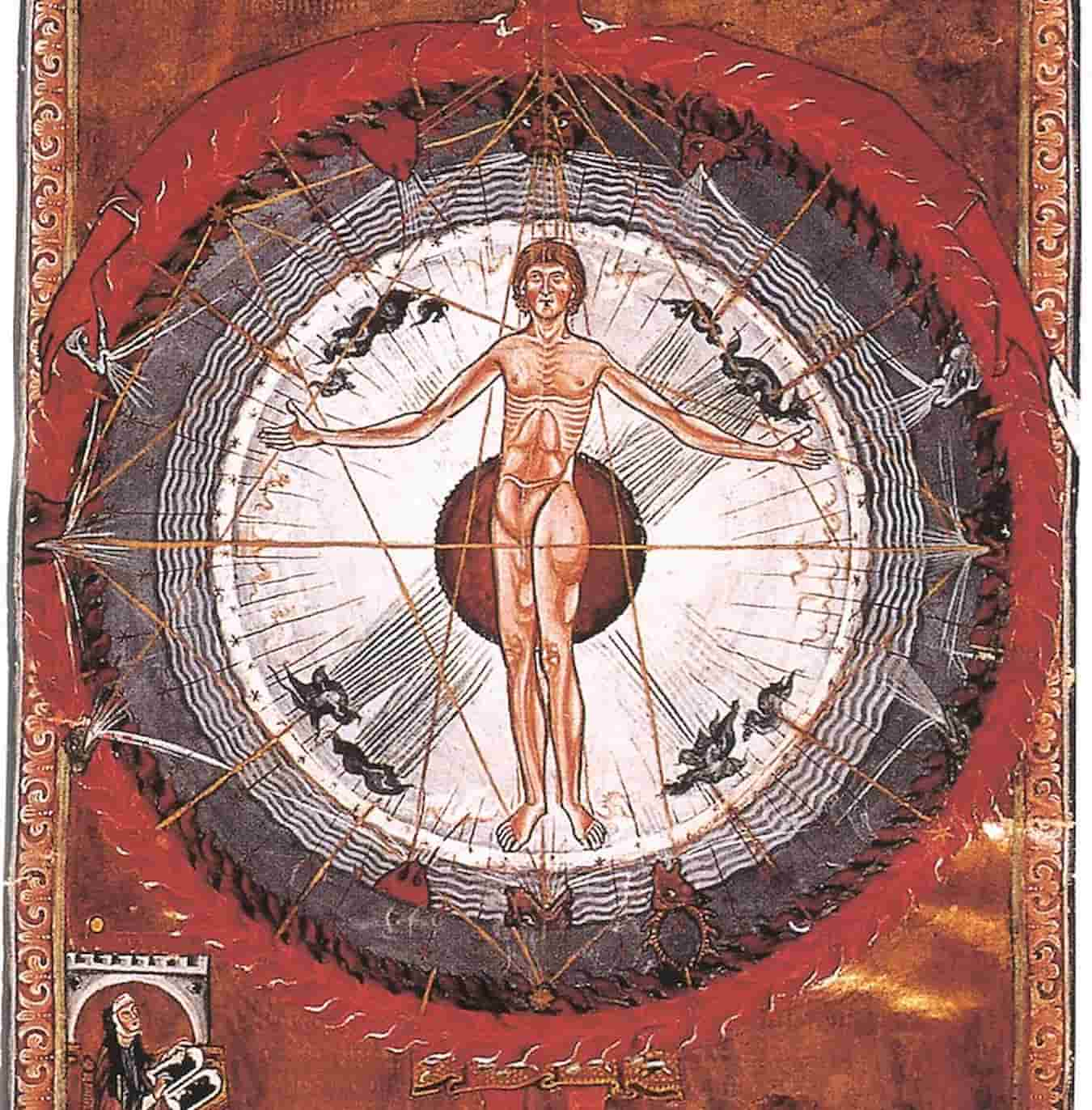

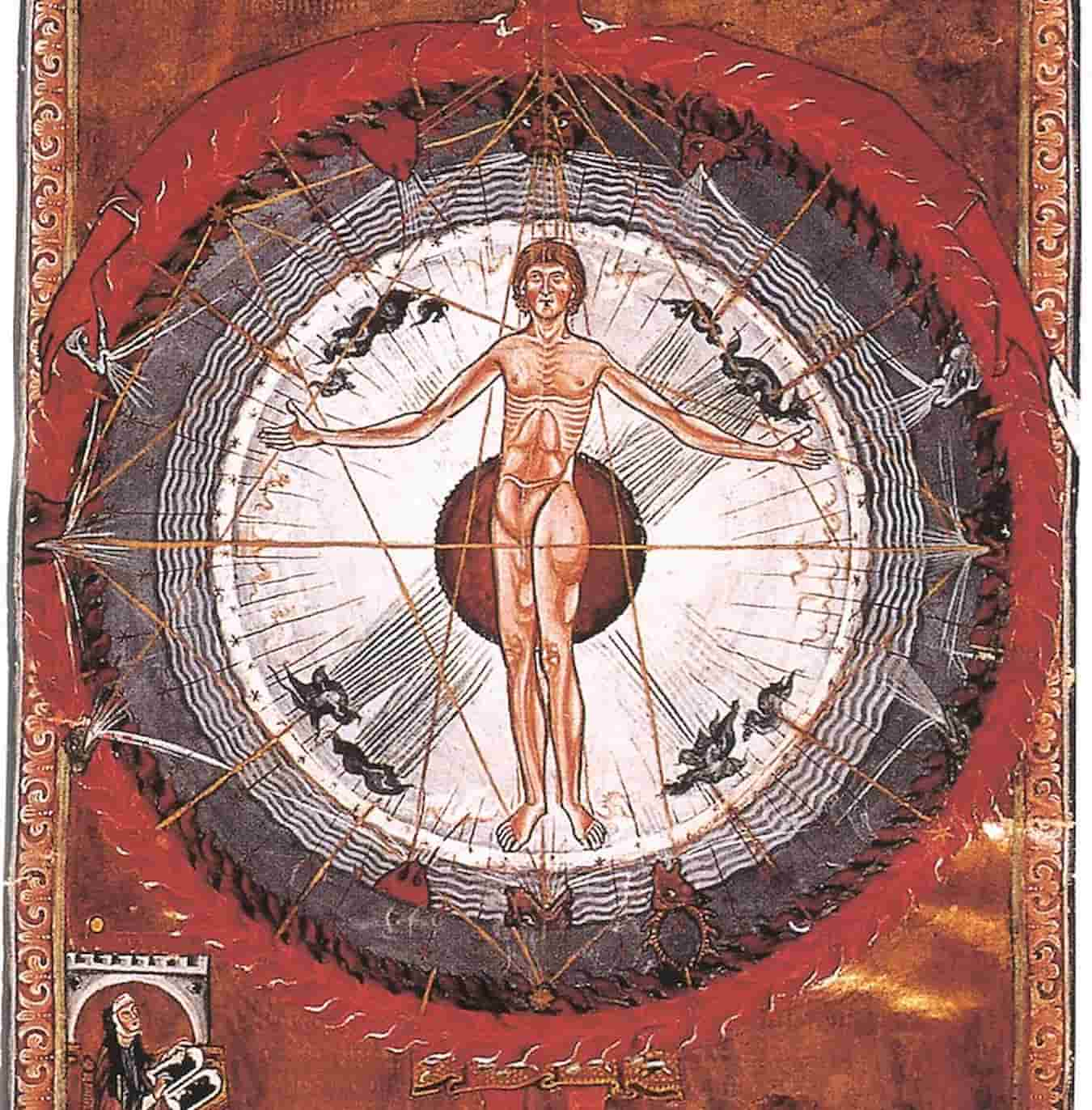

Microcosm: History, Meaning, and Origin

The microcosm is an abbreviation, a reduced image of the world or society. In particular, the term is used sociologically to define a group that is representative of its social background.

The microcosm is an abbreviation, a reduced image of the world or society. In particular, the term is used sociologically to define a group that is representative of its social background.