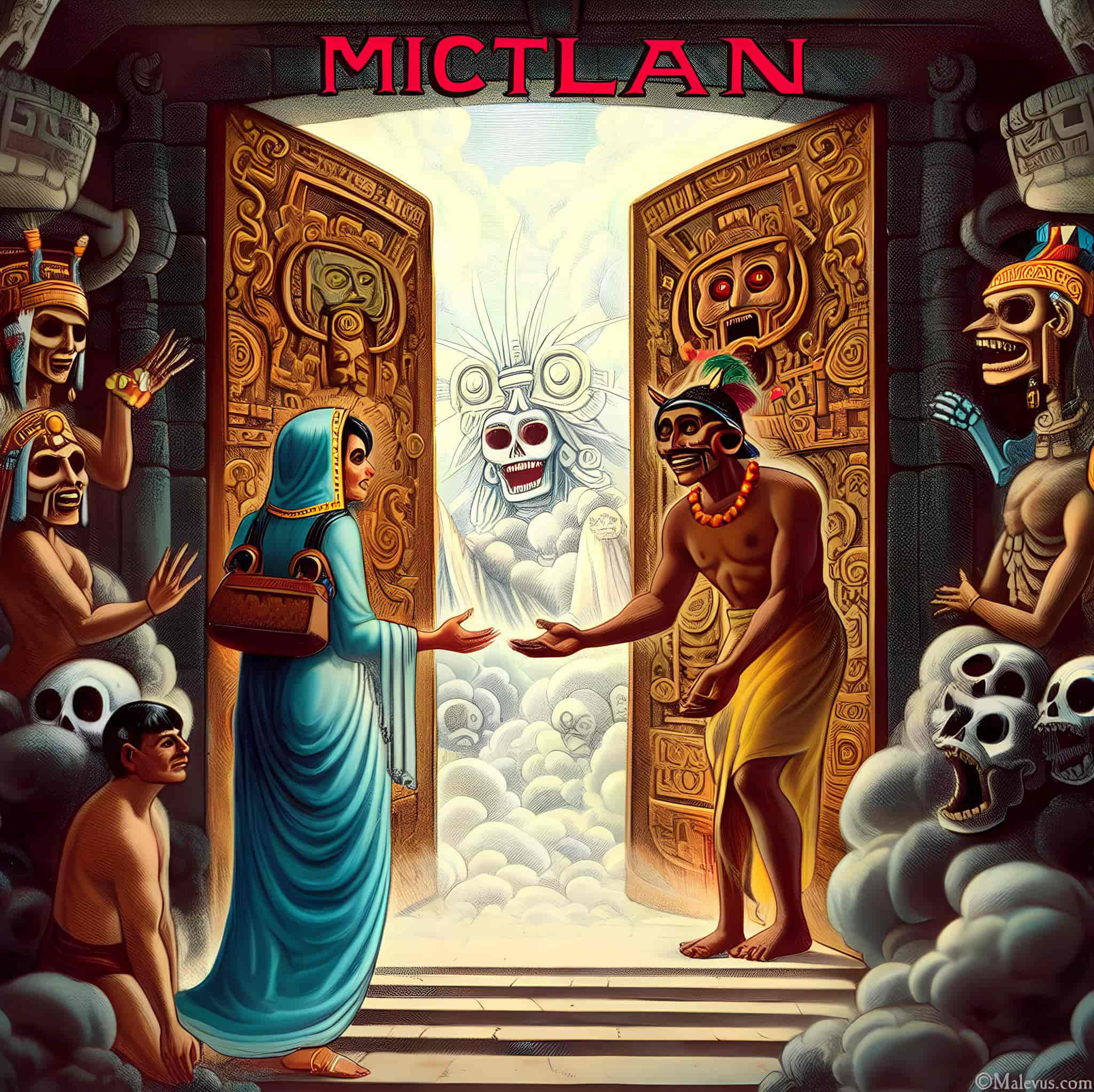

Mictlan, formed from the Nahuatl terms “micqui” (death) and “tlan” (place), translates to “place of the dead” in Aztec mythology. It is the underground regions where the dead must go to free their teyolia (soul, one of the three components forming a person according to the Nahuas people) and vital energy, tonalli. It is also known as Chicunauhmictlan or Ximoayan (“place of the disembodied”). Only those who die of natural causes are allowed to reach this realm, which is commonly referred to as the underworld by anthropologists and is called “tlalmiqui” (from Nahuatl “tlalli” meaning earth and “micqui” meaning to die).

What Exactly is Mictlan?

Mictlan is the underworld of Aztec mythology, and it serves as the last destination for most departed souls, consisting of nine diverse levels, each posing severe difficulties. The dead travel with the psychopomp Xolotl for four years, facing dangerous terrain including smashing mountains, flesh-scraping winds, and blood rivers full of jaguars.

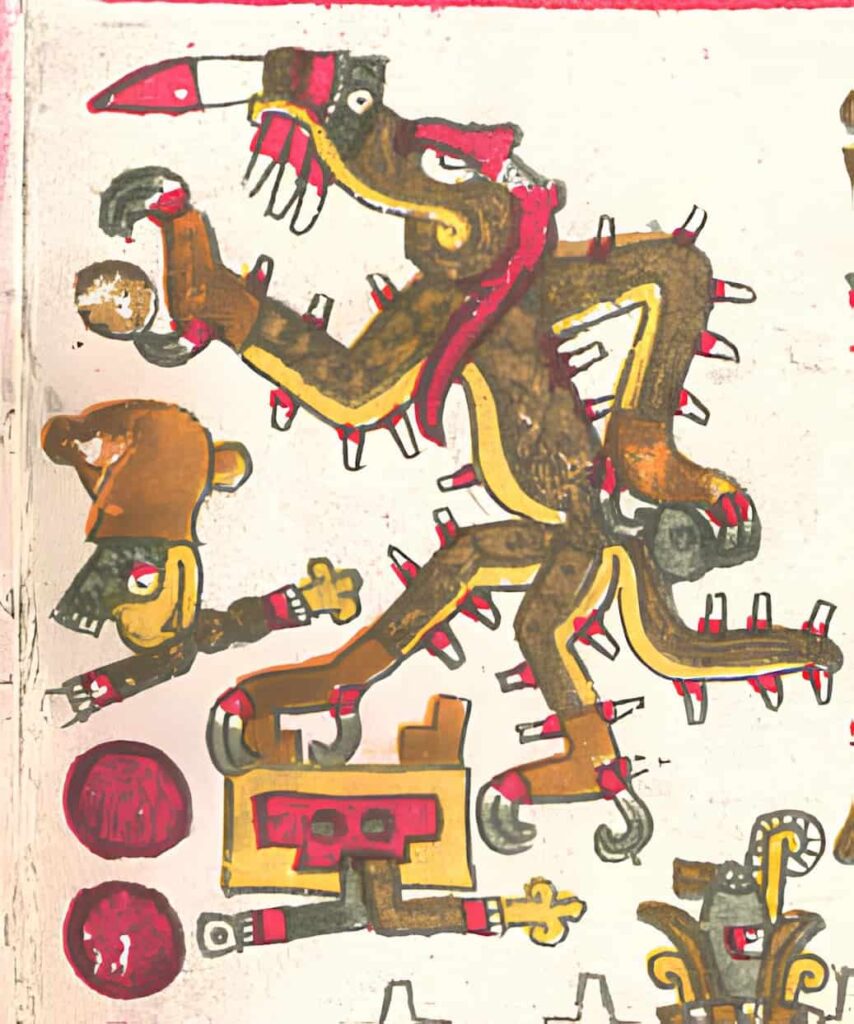

Mictlantecuhtli, lord of the underworld, had a vital part in the Aztec creation story, which makes Mictlan especially significant. In Nahua belief, the realm is an integral element of a cosmos ruled by living forces. Mictlan, controlled by Mictlantecuhtli and his wife Mictecacihuatl, is the last resting place within this cosmological framework.

Those who died for reasons associated with the rain deity Tlaloc still travel to a different afterlife place in Aztec theology called Tlalocan (a paradise). The significance of Mictlan resides in the difficulty of its trip, which reflects the Aztec conception of the afterlife and the interaction of cosmic forces.

Mictlantecuhtli and his wife, Mictecacihuatl, are the de facto rulers of this underworld.

The Funeral Rite for Mictlan

Upon a person’s passing, if they are destined for Mictlan, their limbs are carefully folded and secured, allowing the body to be enveloped in a cotton shroud for the nobility, or ixtle for common individuals which is a resilient plant fiber derived from agave.

The ritual begins with a prayer and the pouring of water over the head, during which it is said, “This is the water you enjoyed while living in the world (Tlalticpac).” A green stone is used as a vessel for the deceased’s tonalli (life energy) during this ceremony by being put in their mouth.

The dead will have the “papers” they need to confront the perils of Mictlan, as indicated by Bernardino de Sahagun. In the Codex of Florence’s Book III appendix, it is detailed how the dead are spoken to and their journey through death is described.

For the last voyage through Mictlan, a dog is sacrificed before the cremation of the burial bundle and the offered gifts. According to Bernardino de Sahagun, the red dog was intended to transport the dead over the Chignahuapan River. Anthropological research consistently reveals this fact.

Although Sahagun explained that only white dogs were capable of facilitating the crossing, later stories often depict a black dog in this role.

The Mexicas used the Xoloitzcuintle dog breed in ritual sacrifices. They maintained them as pets, giving them plenty of love and care, and hoping that someone in Mictlan would identify them by the cotton cords they wore around their necks.

Mictlan in Aztec Mythology

According to Aztec mythology, the afterlife journey of the departed lasts four years and takes them through eight or nine levels of Mictlan’s underworld. There are many perils and tests in store for them on their voyage. The departed go through a series of transformations as they become immaterial and disembodied on their way to freeing their tonalli and teyolia.

Only those who die of old age or common diseases, regardless of their social rank (lords or commoners; macehuales), are allowed passage to Mictlan.

- Tonatiuhichan (Thirteen Heavens) and Ilhucatl-Tonatiuhtl (the Sky Where the Sun Is”) receive ceremonial offerings,

- Macuiltonaleque (the five Aztec gods of excess and pleasure) and Cihuateteo (the Aztec mythology spirits) get soldiers who have died in combat, prisoners who have been slaughtered by their foes, and women who have died giving birth.

- Tlalocan (the Aztec paradise) is the afterlife destination for those who die in water-related accidents or illnesses, or who are devoted to the god Tlaloc.

- Chichihuacuauhco serves as a temporary home for young children as they wait for a second opportunity on Earth.

There is an idiom that mulls over the mystery of death: “Tocenchan, tocenpolpolihuiyan” (variously translated as “our common house,” “our common region where we will go to get lost,” or “the place where all will go”), which implies that all souls, without exception, make their way through Mictlan upon death. According to the 16th-century Florentine Codex, some people’s stays in Mictlan are permanent, while others are only passing through.

Mesoamericanist Christian Duverger suggested the idea that the trip to Mictlan was a “reverse migration,” with the dead following in the footsteps of their northern-bound Mexica ancestors.

Origins of the Mictlan

According to the Aztec founding myth of the world, as told in the Aztec tale of the Five Suns, the universe was organized using the severed corpse of Cipactli, a hungry chimerical crocodile beast that floated in the primordial emptiness and symbolized the earth in the primeval waters.

Its head is utilized to build the heavenly planes of the Thirteen Heavens; its body becomes the earthly space of Tlalticpac (“earth place”); and its tail and extremities are employed to make the realms of the underworld, Mictlan. Nighttime on Earth is inextricably linked to the afterlife because the sun deity Tonatiuh passes through Mictlan at night to shine light on it (a similar story is found in Egyptian mythology with Ra, his solar barque, and his travel to the underworld to raise the sun again).

The Aztec wind deity Quetzalcoatl journeys into Mictlan, gathering the bones of people from earlier incarnations and exploiting them to build the current mankind. But in Gerónimo de Mendieta’s “Historia eclesiástica indiana” (Indiana Ecclesiastical History), the god of fire and lightning, Xolotl, disguised as a Xoloitzcuintle dog, not Quetzalcoatl, travels to Mictlan to get the bones the gods would use to create a new human race. When the gods are sacrificed at the birth of the Fifth Sun, Xolotl, according to Mendieta, plays the role of the priest, not the victim.

The Levels and the Dead’s Trip to Mictlan

Only two primary sources, Bernardino de Sahagun’s “General History of the Things of New Spain,” also known as the Codex Florentine, and the Codex Vaticanus A, also known as the Codex Rios, partially written by Pedro de los Rios, provide substantial information about the journey of the deceased to Mictlan. They have certain things in common but also have some key differences.

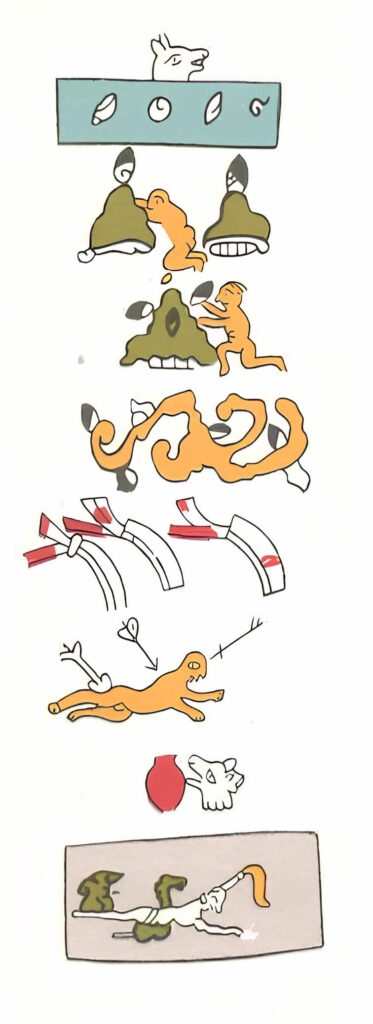

The picture in Codex Vaticanus A is the clearest we have. The first two pages make reference to Latin script and artistically show the travel through eight different levels. Ana Guadalupe Diaz Alvarez, in her analysis of this codex, points out that the artist decided to depict Mictlan as a succession of decedents carrying out various tasks, each of which stands as a discrete time in the story.

When the same artist depicts the heavens, however, everything is clear as day. The “place where flags fly” and the “place where people are signposted,” both of which are referenced in this codex, remain mysteries. According to Nathalie Ragot, we still don’t understand these two sections of Mictlan.

The Spanish mesoamericanist Sahagun also talks about eight layers of Mictlan, although his description and arrangement are different. There are Nahuatl proper nouns in the Codex Florentine. Christian Aboytes presents a nine-tiered Mictlan in “Amoxaltepetl, El Popol Vuh Azteca,” with descriptions of each tier.

The Location of the Mictlan

Mictlan, ruled by Mictlantecuhtli and his consort Mictecacihuatl, is a dark and foul place at the center of the earth (in Nahuatl, “Tlalxicco,” derived from “tlalli” meaning “earth” and “xicco,” the locative form of “xitli” meaning “navel“), located on a vertical plane where the world consists of Thirteen Heavens and the realms of the afterlife.

Mictlan’s horizontal position is less often discussed. In Molina’s lexicon, “Mictlampa” (which means “on the side of Mictlan”) designates the geographic north. Humanity’s home on Earth, called “Tlalticpac,” expands laterally in comparison to the vertical realms of the heavens and the afterlife in Mictlan.

Mictlan is consistently linked to “topan” (on, above) in Nahua oral ritual practices, as analyzed by Ana Diaz in “Cielos e inframundos” (Heavens and Underworlds). As in the phrase “in topan in mictlan in ilhuicac” (above us, in Mictlan, in the sky). The author underlines the lack of connection between the name Mictlan and a space lying below or beneath the earth. This raises the possibility that Mictlan was seen as belonging to the cosmos.

Given its reciprocal connection with regions plainly indicated as superior by the word “ilhuicac” (heaven, paradise), it is difficult to associate Mictlan with a definite and tangible place. It’s a realm of imagination and choice, where things may be imagined and decided just as they are. It’s less about describing the underworld and more about describing the otherworld or the beyond.

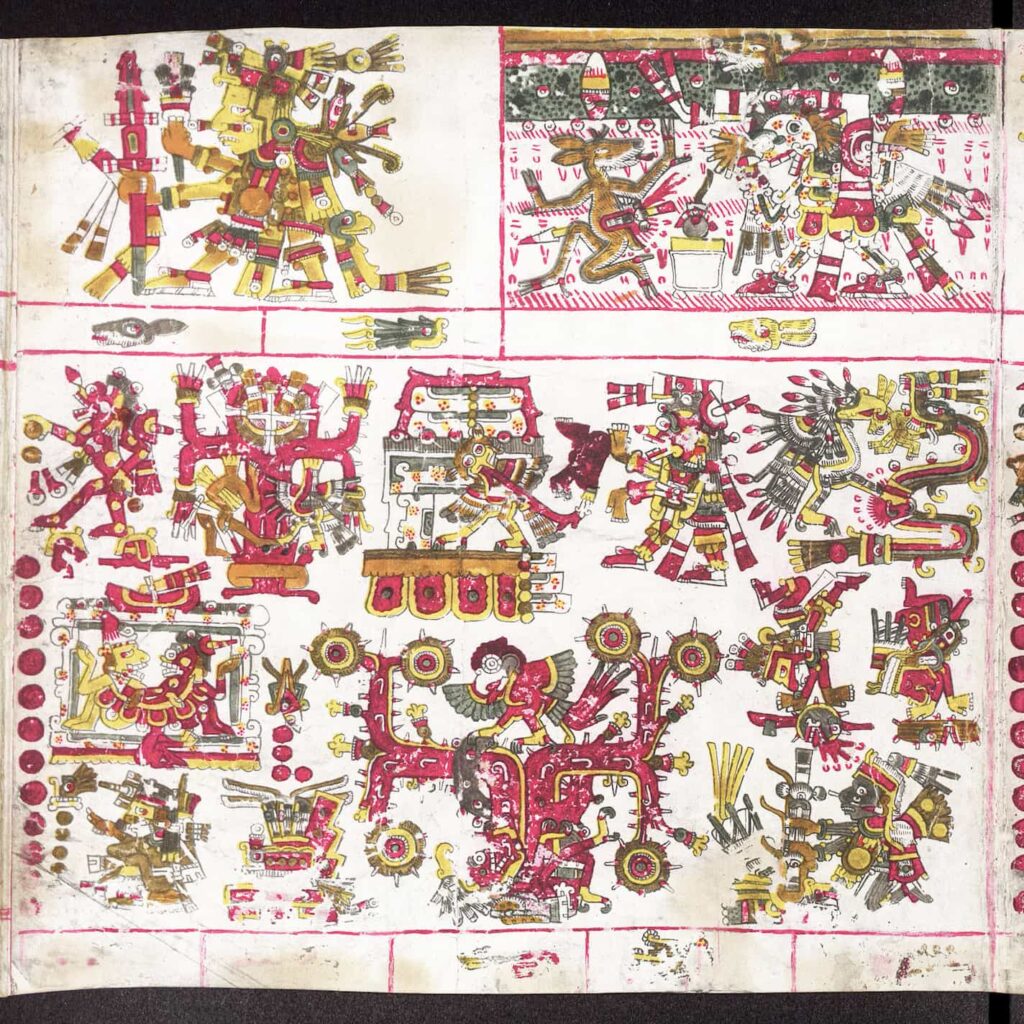

Ana Diaz claims that the images on pages 29 and 30 of the Codex Borgia show how the four gods of creation view the upper and lower worlds as fundamentally similar, but that their differences are due to the ritual action of words and offerings that precede and direct their creation.

In her article on the Nahuatl concept of “ilhuicac” (heaven), which she applies to an examination of Mictlan’s location, Katarzyna Mikulska argues that the vertical axis is not so clearly divided between day and night but rather between the diurnal and nocturnal aspects of vertical spaces. She claims this is supported by the artistic depictions of the night sky and Mictlan underneath the ground seen in ancient codices. Colors, which may also symbolize directions in space, are used to show the differences between the nighttime sky and the daily sky. The north is represented by black, the south by blue, the east by red, and the west by white.

Terminology

Mictlan was not the exclusive word utilized in early Aztec and Spanish sources. In addition to Mictlan, indigenous people also employed a number of additional terms to describe various elements of this underworld.

This level is also known as “Ximoayan” (or “Ximoan”), which translates to “place of the skeletal ones.” This idiom refers to how the departed feel after making it to Mictlan from wherever they passed on earth. “Chicnauhmictlan” (also known as “ninth place of the dead”) is a geographical phrase that places Mictlan on the ninth and last tier of the underworld. It is sometimes called “tlalli inepantla,” which literally translates to “at the center of the earth.” If you ask Nathalie Ragot, it means “more in the heart of the earth than at the center, in the sense of depth.”

In their lack of understanding, Spanish chroniclers incorrectly linked Mictlan to the Christian concept of “hell,” using the Spanish word “infierno,” which was translated as “inframundo” in subsequent translations and further contributed to geographical misunderstanding. Even though these two views of the underworld occasionally have parallels, as occurs with other faiths, this relationship is actually inaccurate.