European moles reduce their brain size and, in some cases, their skull size to save heat during the colder months. Biologists have found that their heads shrink by 11 percent throughout the winter and do not regrow until the spring. In contrast to humans, mature moles may undergo significant brain and skull bone regeneration. This offers promising new avenues for the medical field as well.

Moles have to fight it out all winter long, unlike their hibernating counterparts like hedgehogs, bears, and dormice. Even in cold weather, their metabolism remains high, making them one of the most energetic mammalian species. Because of their high energy requirements, moles must feed continually, even in freezing conditions when food is scarce. How do they pull this off in the first place?

The Remarkable Dehnel Phenomenon

This question has been answered by Lucie Nováková and her coworkers. The researchers were on the lookout for phenomenon in Iberian and European moles that had previously been seen in shrews, stoats, and weasels, all of which share the mole’s fast metabolic rate and do not hibernate during the winter.

Their unusually high metabolic rates allow them to remain active during the whole year. But their little bodies burn up their reserves of energy in just a matter of hours. To save energy and food throughout the winter, these little animals undergo reversible shrinkage of their brains, skulls, and other organs.

It looks like moles experience the so-called Dehnel phenomenon too. Nováková and her team of researchers used museum collections to examine the skulls of European and Iberian moles to compare the skull sizes of similarly sized animals that died at various periods of the year.

Winter Causes An 11% Decrease In Skull Size

According to the results, the European mole’s skull size does vary significantly from one individual to the next. And the animals’ average head size decreases by 11% between summer and winter. Skull growth resumes in the spring, although it is only around 4% larger around this time. It is found that the largest size disparity occurs in the first year of the mole.

This demonstrates that the moles employ the Dehnel phenomenon to survive the winter. Moles’ brain sizes decrease in the winter, so they can get by on a smaller food intake. The European mole joins the shrews and the marten family of stoats and weasels as the only other mammalian groups to exhibit this brain-shrinking adaptation.

The Cold Weather Triggers Brain Shrinkage

It’s also worth noting that Nováková and her colleagues were able to identify the trigger signal for brain shrinkage in the European mole by contrasting it to the Iberian mole, which is native to Portugal and Spain. If it were just a question of food, the European mole would have to shrink in the winter when food is limited, and the Iberian mole would shrink in the summer when the high heat and dryness made food rare.

However, the studies demonstrate that the skull size of the Iberian mole never changes. The lack of seasonal variation in skull size among this mole species lends credence to the theory that frigid winters are at least partly to blame for the emergence of the Dehnel phenomenon. One piece of evidence that points to an external trigger, like winter temperatures, is the fact that European moles shrink their skull sizes every year.

This Could Be Useful In the Medical Field

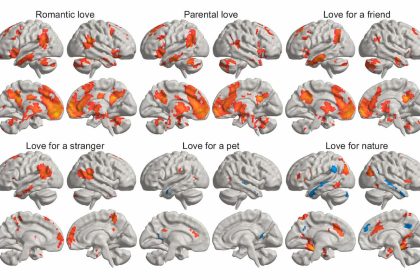

The Dehnel phenomenon seen in moles provides new insight into the winter survival strategies of these skilled burrowers. They may now also aid in understanding the biological and evolutionary context of this out-of-the-ordinary adaption. The greater the diversity of mammalian species that can be detected using Dehnels, the more applicable the biological discoveries will be to other mammalian species and potentially even to humans.

The Dehnel effect could provide useful jumping-off points for medical studies. Mammals, including humans, have a very little window of opportunity for full brain and skull regeneration once they reach maturity. However, moles, shrews, and weasels must have unique cell biology and genetic systems to annually reduce and increase their brain and skull size.

The ability to shrink and regenerate bone and brain tissue in three species of mammals (shrews, weasels, and moles) offers tremendous promise for the study of degenerative conditions like Alzheimer’s and osteoporosis.

Sources:

- Lucie Nováková, Javier Lázaro, Marion Muturi, Christian Dullin, Dina K. N. Dechmann. Royal Society Open Science, 2022; 9 (9) DOI: 10.1098/rsos.220652