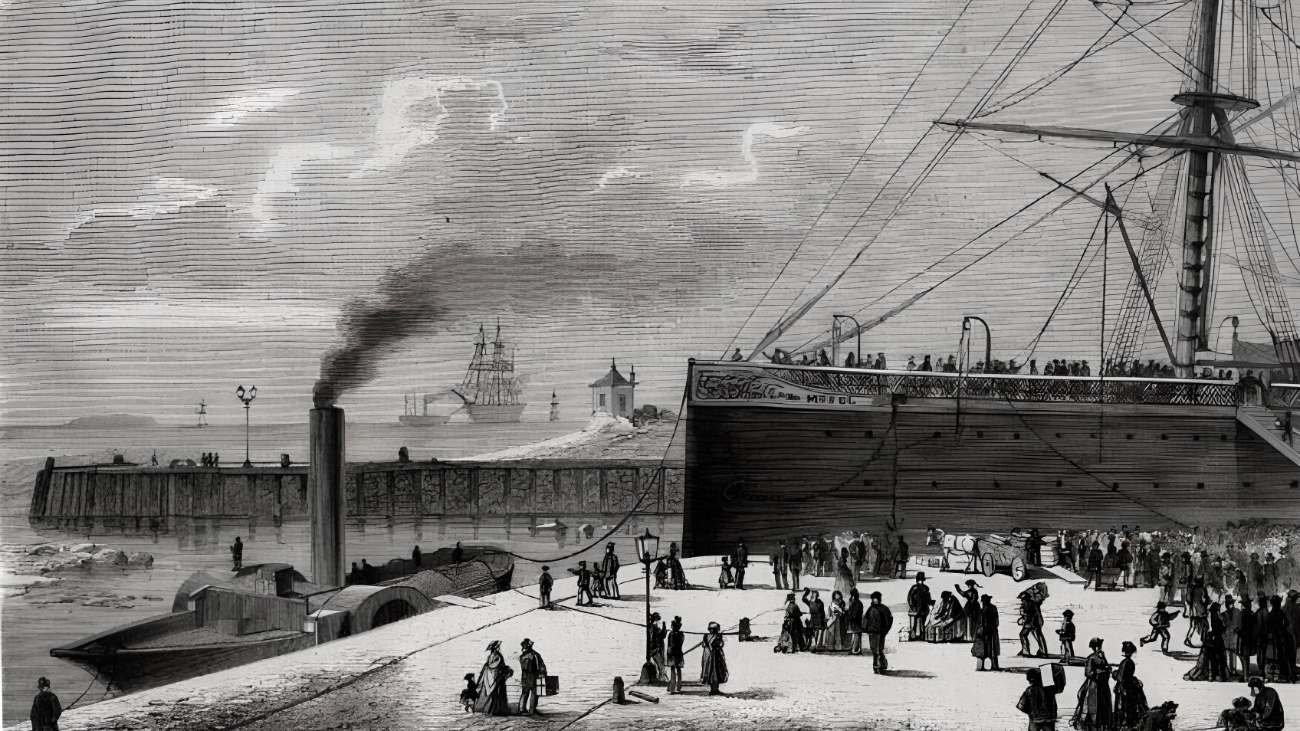

At about 11 a.m. on December 11, 1875, a massive explosion took place in Bremerhaven. Just then, the last of the cargo was being put onto the steamer “Mosel,” which was about to depart for Southampton and then continue on to New York. Most of the passengers were southern Germans who were looking to leave their homeland and begin a fresh life in the United States.

The “Mosel” was a North German Lloyd (NDL) steamer. NDL was the largest German shipping firm, rivaling even the Hamburg America Line (HAPAG). Both businesses relied heavily on immigrants as a revenue source, alongside freight.

The pier and other areas of Bremerhaven were destroyed when an explosion shook the area in the winter of 1875. A 13-foot-deep (4-meter) crater was all that remained. There were at than 80 fatalities and hundreds of injuries. Where did all of this terribleness come from? When the dust settled, everyone knew the explosion had happened on the hull of the ship. The calamity had been triggered by a “hell machine” buried in the barrel, according to preliminary investigations.

Moving to a new place

The immigrants crossed the ocean on the massive steamships of the shipping firms, which were increasingly replacing sailing ships at the period. Liner service between continents became feasible with the advent of swift steamers, which were less reliant on the wind. The Atlantic crossing took between 10 and 14 days.

This meant that by the time World War I broke out, more people were leaving Europe than ever before. The shipping industry reaped huge financial benefits as a result. The annual influx of German immigrants to the United States averaged over 120,000 in the 1880s. By the turn of the century, they had become the most numerous immigrants to the United States.

The majority of immigrants traveled across the Atlantic in steerage since it was the least expensive but most uncomfortable option. Steerage passengers were not afforded the same luxuries as those in first and second class. Bedframes were instead lined up and then shifted to the side on the return journey to make room for more freight. The “Mosel,” a freight and passenger ship that provided liner service between Bremerhaven and New York, was not finished until 1872. Almost seven hundred people could fit on the tween deck.

The ship was set to leave for Southampton and then New York on the day of the accident. 600 people to be on board. But the NDL steamer “Deutschland” had recently sunk on December 6 after running aground on a sandbank outside the mouth of the Thames, prompting the crew to make an emergency stay in England. Fifty or more people had lost their lives because of the incident.

Reasons for the Mosel disaster

The survivors were brought to Southampton, where they awaited transport to the United States on the next vessel, called the “Mosel” from Bremerhaven. But then things took an unexpected turn for the worse. There was still a cart at the dock, loaded down with boxes and barrels. One of the barrels was constructed from iron-shod, dark brown wood.

According to the bill of lading, the container weighed 1.3 tons and included high-priced iron components. Today, it seems likely that the barrel fell into the road after slipping from the grip of a port worker operating a crane.

There was a huge bang. It is hard to piece everything together, but it is understood that the collision activated an ignite mechanism in the barrel, which contained lithofracteur (an explosive compound of nitroglycerin). While the original dynamite recipe was developed by Alfred Nobel (1833–1896), the Lithofracteur explosive combination had more explosive potential.

Several hours after the explosion, a man was discovered critically injured in a first-class cabin and sent to the hospital. First responders assumed he had been killed in the blast, but then they discovered a pistol inside the cabin with two empty rounds. It seems the man had attempted suicide. A quick check revealed that the barrel in question was really his.

For fraudulent insurance claims

The guy’s name was Alexander Keith Jr., and he was a Canadian of Scottish descent. As William King Thomas, he traveled over Europe. Keith, who had accumulated a lot of debt, decided to conduct insurance fraud as a means of getting out of his financial bind. Keith paid a hefty premium to insure a shipment of useless goods that was certain to be destroyed in a bombing raid at sea.

However, the bomb wasn’t supposed to detonate for a few days, somewhere in the middle of the Atlantic. He preferred to get off the ship at Southampton, where he thought the survivors from the sinking of the “Deutschland,” the “Mosel,” would also be able to embark.

Keith was gravely hurt in the incident and later admitted his guilt, but he passed away on December 16th, five days after the incident, thus he was never brought to justice. The Bremen police department’s examination of the case uncovered disturbing information.

By 1873, Alexander Keith was already plotting to murder hundreds of people in return for a large insurance payout. In that year, he went to a watchmaker and asked him to construct a mechanism that could operate quietly for a few days before triggering the detonator with a hard blow. He bought the explosives while pretending to be a Jamaican mine owner.

By the way, the assault on the “Mosel” was his third attempt. He had previously planted a bomb aboard the NDL ship Rhein in the summer of 1875. He was disheartened to learn that the ship had made it to New York but that the firing mechanism had seemingly failed.

Because no other shipping company would take his shipment without first checking it, he made the trip to Bremerhaven to give the “Mosel” a go. Unfortunately, the transportation firm took the box anyhow. Since no further suspects could be located and Alexander Keith was already dead, the inquiry was closed in 1878.

These days, few people remember what happened during the incident. Unfortunately, it seems that not even the little metal plate that marked the site of the disaster near the entrance to Bremerhaven’s New Harbor has survived.