In the same era that sea travel and commerce emerged, so did pirates. Near key commercial routes, piracy was a problem in both ancient and medieval times. The goal wasn’t only to earn money off of other people’s misfortune but to eliminate potential rivals in the market as well. The practice of piracy was not only a common aspect of the medieval economic system but also an efficient tool of foreign politics.

The Great Geographical Discoveries unquestionably sparked global economic upheaval. Sea commerce had evolved into an ocean trade, and the medieval market masters, Italians, and Hanseatics were no longer a part of it. Countries, rather than cities or coalitions, took control of the conflict. Over the next three hundred years, the Portuguese, Spanish, Dutch, English, and French fought for control of the trade routes with the unstated motto “beat the neighbor.” Maritime robbery, which was frequently condoned by authorities, was a primary weapon in this conflict. This is the origin story of pirates like corsairs, raiders, and privateers.

From the 14th to the 19th centuries, as states vied for control of the Mediterranean Sea, they gave licenses to individuals known as “corsairs,” who were known as captains and their crews. Kings employed pirate mercenaries known as raiders, whose primary duty was not to plunder but to destroy enemy ships. Even if the enemy ship was plundered before it sank, the prize would go to the government that hired the raiders.

Privateers, sometimes known as “privates,” were pirates who held a “privateer’s certificate,” permitting them to target ships from a particular country. Attacking and fighting solely under the flag of the country that provided the certificate was one of the restrictions that privateers had to abide by. If they broke the terms of the agreement, the privateers reverted to being regular pirates. Some of the most well-known pirates from the 15th to the 18th centuries are talked about below.

Victual Brothers (Late 14th to First Half of the 15th Century)

At the end of the 1400s, a group of pirates called the Victual Brothers (also called the Vitalien Brothers) often attacked the ships of Hanseatic League merchants who traded in the Baltic and North Seas and the English Channel.

In his conflict with Queen Margrethe of Denmark over the throne of Sweden, King Albrecht of Mecklenburg of Sweden enlisted the aid of privateers. Mecklenburg dukes declared their harbors open to anybody who “dared to cause damage to the Danish kingdom at their own risk” during the queen’s siege of Stockholm in 1391. “They robbed both their own and foreigners, which made herring exceedingly dear,” the chronicle states of the Victuals, who raided the ships of King Albrecht’s friends.

Gotland, previously under Danish rule, fell to the Victuals in 1394, who promptly turned the island’s city of Visby into a fortress. The Victual brothers kept on pillaging even after peace was signed between Sweden and Denmark in the late 1400s. The Hanseatic League’s ships may have had more armament and guards because of need, but it didn’t help much. Between the Vitaliers and the Hanseatic League, there was actual combat. Pirates whose ships were captured had to be transported ashore in herring barrels before being tried and killed.

Klaus Störtebeker is the most infamous of the Victual pirates. Virtually nothing can be confirmed about him, but a remarkable narrative surrounds his demise: Störtebeker is said to have asked the mayor of Hamburg to release as many of his pirate crew as he could walk past after being beheaded. And with his severed head in his hands, he passed by 11 people. But then the executioner set his foot on the ground, and his decapitated body collapsed to the ground. Despite his promise, the burgomaster ordered the execution of all of them.

A historical novel titled The Victual Brothers was written by German author Willi Bredel in the 1950s, and a film titled Störtebeker was released in 2006.

Hayreddin Barbarossa (1475-1546)

Barbarossa represents the conflict between Muslims and Christians in the East and the Western world for control of the Mediterranean Sea. Khidr was born on the island of Lesbos, then part of the Ottoman Empire, to a Muslim father and a Christian mother. His older brother Oruç and he were first exposed to the water as they helped transport their father’s products, but they quickly turned to a life of piracy. Eventually, Oruch, a member of the crew himself, led a revolution that propelled him to the position of captain. The brothers stood out because of how brave they were in battle, and their crew quickly became known as a threat all over the Mediterranean.

They won the conquest of Algeria in 1516, and Khizir, upon the death of their older brother Oruch two years later, took on both the acquired regions and the Barbarossa moniker (“Redbeard”). Barbarossa acknowledged the Ottoman Empire’s authority and declared himself sultan of Algeria. Hayreddin, which translates to “Good of Faith,” was the name Muslims gave him since he was widely recognized as a supporter of Islam. We know that Barbarossa looked fierce because someone once said, “He had shaggy eyebrows, a thick beard, and a thick nose.” A large portion of his heavy bottom lip stuck out condescendingly. It was said of him, “On one outstretched arm, he could hold a two-year-old sheep until it died.” He was of average stature, but he had an abundance of strength.

Hayreddin was put in charge of the whole Turkish navy by Sultan Suleiman I, the Magnificent of the Ottoman Empire, who employed him in his efforts to unite the Turkic world. Genoese, Venetian, Spanish, and Maltese knights were all adversaries of the legalized pirates. He conquered the Italian coast and defeated them in Tunisia and Algeria. Turkey flourished under Hayreddin’s rule and became a dominant maritime force in the Mediterranean.

Barbarossa was one of the few gentlemen of his social standing to spend his latter years in Istanbul, where he was also given a memorial mosque.The inscription on his tomb’s gray granite slab reads, “Here rests the beylerbei of the sea.” For a long time now, ships passing by have saluted the mosque in honor of Barbarossa because of its waterfront location. The Catalan author Juan Pons published a novel titled “Barbarossa” in 2006.

Francis Drake (c. 1540 – 1596)

The most infamous pirate of the Elizabethan Era, Francis Drake, was also the first Englishman to circumnavigate the globe. The Spanish Armada was decisively defeated because of his heroic actions in the Battle of Graveline (1588). Many English books, novels, and plays use him as a villain, although he is the hero in Lope de Vega’s poetry, “La Song de la Danse.”

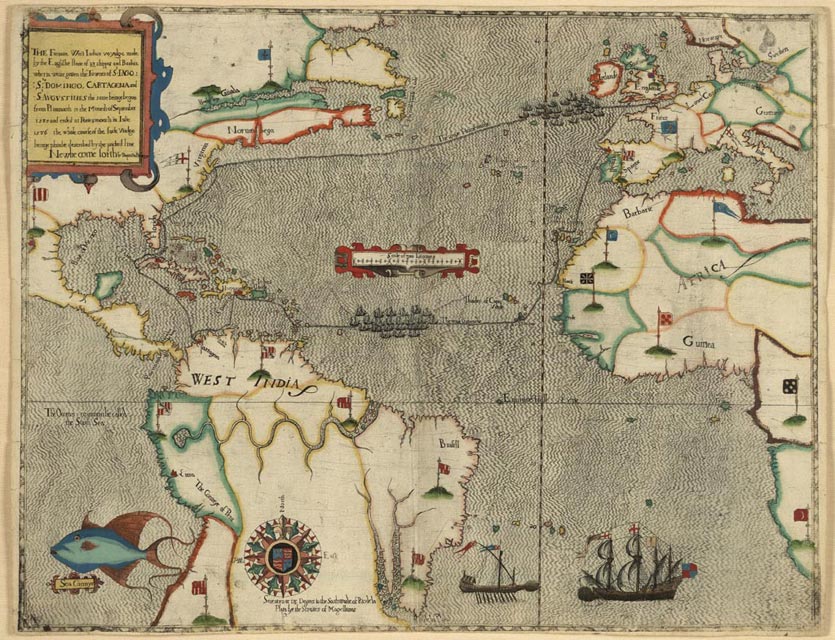

Drake was assigned to John Hawkins’s ship when he was a young man because of their shared ancestry. Hawkins was a pirate and slave dealer. During the early 1560s, he joined a slave voyage to West Africa and rose quickly through the ranks to captain. When Drake, Hawkins, and their crew attempted to enter a Mexican port in 1568, the Spanish blocked their path. They managed to get away, but not before losing several soldiers.

Despite the mission’s failure, Drake became a public figure and won the approval of Queen Elizabeth I. Drake’s subsequent, already-independent voyage was on the queen’s behalf; in fact, it gave her permission to seize any property belonging to King Philip II of Spain. Drake arrived on the Isthmus of Panama and took control of a caravan transporting precious metals from Peru. Drake returned to England with not just his haul but also a stellar reputation as a skilled privateer.

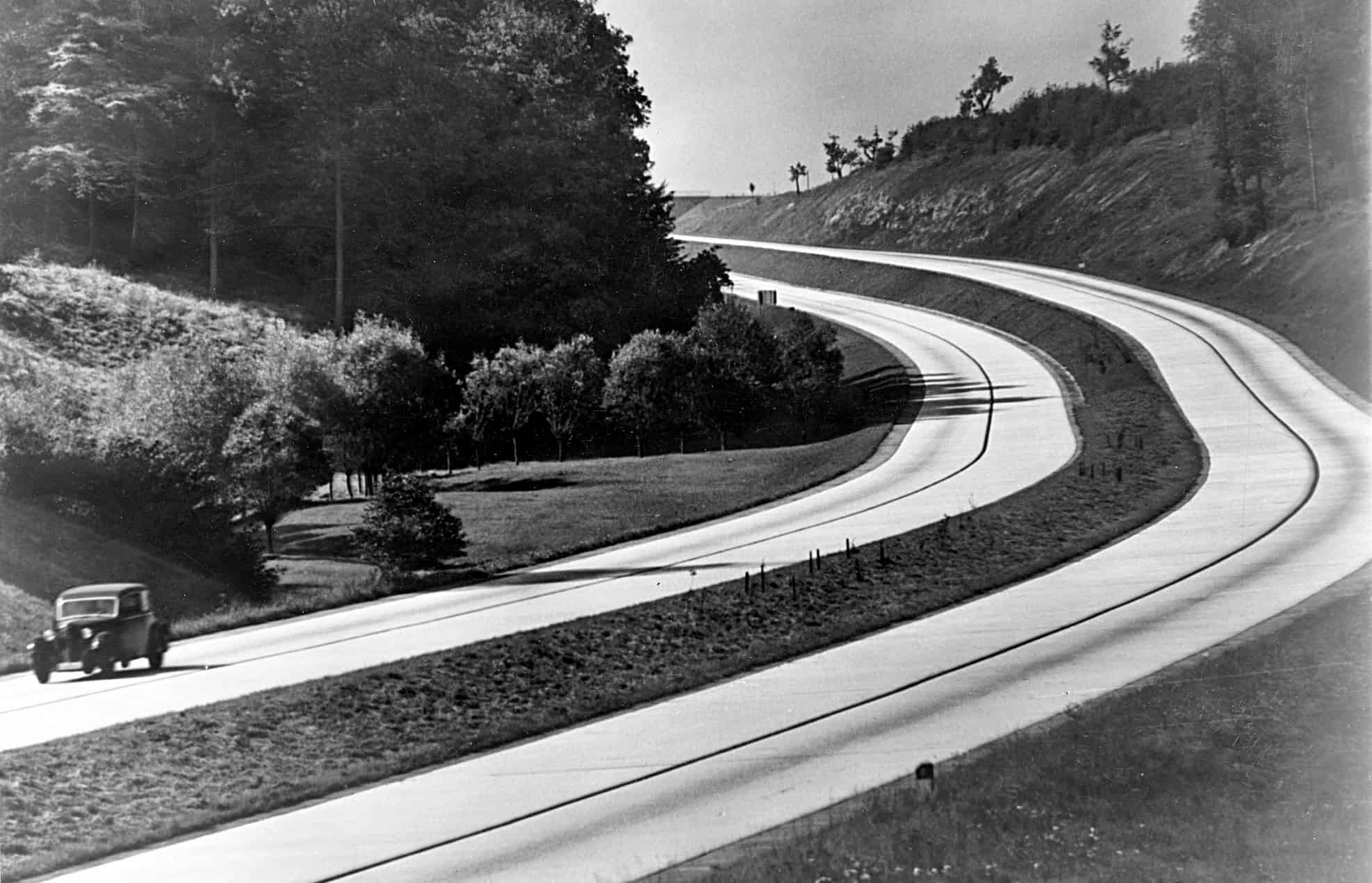

The massive galleon Our Lady of the Immaculate Conception was transporting gold and silver from Callao to Panama when it was caught by Drake and his fleet of five ships in 1579. The expedition’s return on investment was an astounding 4700% of costs. Drake’s exploration of the west coast of North America, the discovery of San Francisco Bay, and the naming of the passage between the southern Atlantic and Pacific seas after him all gained him genuine recognition during this mission. His journey was the first Englishman’s tour of the world. Drake’s flagship, the Golden Doe, was visited by the queen, who knighted her most famous commander.

There was nothing wrong with Sir Francis’s life. He was elected to the House of Commons in 1584 and served as mayor of Plymouth, inspector for the Royal Commission responsible for overseeing the Royal Navy, and owner of an estate complete with a castle. He launched another expedition in the fall of 1585 with the goal of doing as much harm to the Spanish as possible.

Drake landed on the coast of Spain with a fleet of 25 ships and 2,300 sailors and soldiers. They captured the town of Vigo and made off with 30,000 ducats. From there, he sailed to the Cape Verde Islands, where he made a landing before plundering and destroying every colony before crossing the Atlantic to attack the West Indies and the capital of the Spanish territories in the New World, Santo Domingo. His reward was a galleon docked in the harbor, in addition to 25,000 ducats and 250 fortification cannons. In response, the decision was made to launch an attack on Cartagena, the most prosperous port in all of Spanish America. For over a month, he laid waste to the city before the Spanish gave up and fled. For days, mules hauled precious metals to Drake’s ships. In the summer of 1586, when Drake finally chose to return to Plymouth, he did so with a haul worth almost £350,000.

Drake had been on land for eight months when he was assigned a new mission: sink the fleet Philip II was assembling to attack England. He charged into Cadiz’s harbor, where they were waiting, and sank 30 ships and looted hundreds of tons of supplies. The fleet then set sail towards the Azores, plundering other ships en route. Drake fought alongside the Spanish Invincible Armada in 1588 in his capacity as vice admiral. Although they had twice as many ships and weapons as their opponents, the Spanish eventually withdrew after losing 60 of their 130 ships. Even England’s adversaries adored Drake. His pontificator, Sixtus V, praised him as an outstanding leader.

Drake’s final voyage occurred in 1595. Drake planned to take Panama, but a dysentery outbreak swept through the flotilla, ultimately claiming his life. His body was buried at sea with a burst from the ship’s guns near the island of Buenaventura. In 1596, when it was learned that Drake had died, the news was met with grief in England and celebration in Spain.

Drake’s flagship, the Golden Doe, was left at Deptford, London, as a museum to commemorate the 1577–1580 circumnavigation. The ship was docked for nearly 70 years before succumbing to water damage and possibly an insect infestation. The chair, which was fashioned from a Doe beam, may be seen today at the Bodleian Library in Oxford.

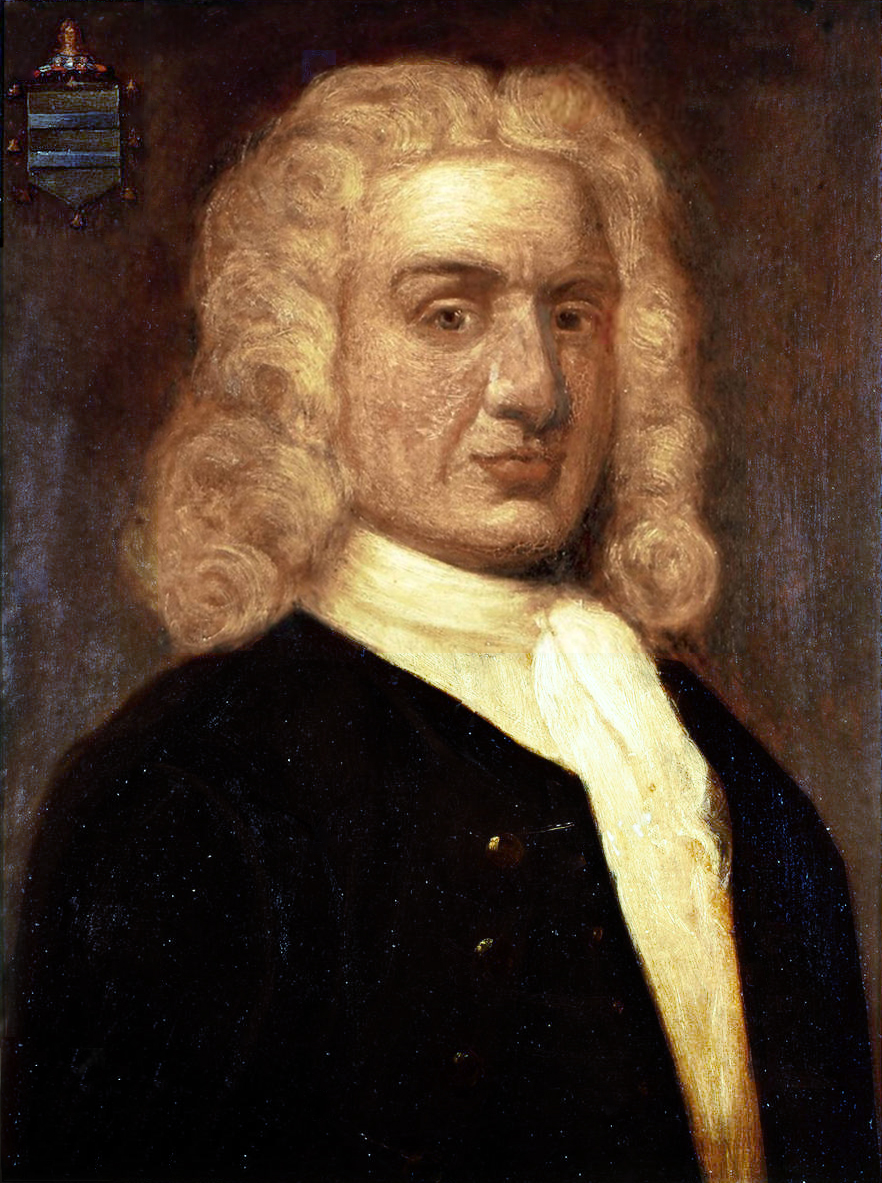

William Kidd (c. 1645 or 1655 – 1701)

William Kidd was supposedly the son of a clergyman who drowned at sea and was born in Scotland. While the details of Kidd’s childhood are sketchy at best, it is generally accepted that he spent some time at sea. Some believe that French pirates picked up Kidd from a shipwreck off the coast of Haiti after he had been serving in the English fleet. In either case, in 1689 records, he leads an English crew on a 16-gun French ship.

Together with Thomas Hutson’s pirate armada, Kidd stole a 20-gun ship from French freebooters and renamed it “Blessed William,” then began ravaging the West Indies while flying the English flag. Kidd lost his Blessed William to a mutiny in his own crew immediately after he assumed command of his whole fleet in retaliation for Hutson’s rebellion. Kidd traveled to New York aboard a ship captured from the French, where he took part in the transport of guns to the New World, married a wealthy widow, and acquired daughters.

New York’s new governor, in 1695, hired the “trusted, well-established” Kidd to clear Pacific trade channels and lead a punitive expedition against the region’s most infamous pirates and any enemy French ships. Kidd, armed with a privateer’s certificate and intent on taking on the French and their 34-gun ship Adventure, set out towards London.

Unfortunately for the captain, things went downhill from there: the ship was poorly constructed and required regular maintenance; they never saw a French ship on the way; the crew attempted to mutiny; and Kidd murdered one of the crew, an officer (a very serious offense under the laws of maritime law in the 17th century). After a long chase, the Kedah Merchantman finally caught up with the Adventure in January 1698. However, Kidd’s license was only valid against the French; the captain of the ship, John Wright, was an Englishman, and the owners of the cargo were Armenian merchants. Yet Kidd pillaged the vessel, selling its contents for 25,000 GBP (including silk, satin, gold, and silver). What the captain did was incredibly scandalous on a global scale. Kidd’s privateer’s certificate was nullified, and he was added to the federal pirate watch list.

Kidd set sail for New York, hoping for safety under the watchful eye of Lord Belmont, the governor of New York and Massachusetts. But Belmont had him arrested and sent off to stand trial in England. The trial started in the early spring of 1701. The trial started in the spring of 1701, with the pirate being charged with murdering officer William Moore and five counts of piracy. Kidd himself made no admissions and denied all of the allegations, calling them slander, and none of his former patrons defended him. His punishment included execution by hanging. English King William III did not grant clemency to a former privateer who had served during his reign.

The rope snapped, and Kidd was hung twice in a very horrible manner. The captain and his collaborators were hanged, and their remains remained there for three years along the Thames. In the wake of this tragedy, a song called “Captain Kidd’s Farewell to the Seas” went viral, singing the captain’s praises and defending his character.

Henry Morgan (1635-1688)

As the inspiration for Captain Blood in Rafael Sabatini’s Captain Blood: His Odyssey and for Will Turner in John Steinbeck’s Cup of Gold, the real-life Captain Morgan was a renowned and successful English pirate who rose to become the king of the Caribbean’s rogues. Morgan did file a lawsuit against the book’s publisher after the 1678 release of the English translation of Alexander Exquemelin’s The Buccaneers of America because he took offense at being labeled a pirate. He took exception to being called a pirate and testified that he had never had anything but contempt for pirates during his whole life. As a result of his victory, he was awarded £200 and issued an apology in open court.

The true circumstances behind Henry Morgan’s arrival in the West Indies are unknown. He apparently grew up in a prosperous farming family in Wales before joining Oliver Cromwell’s army in 1654 in Portsmouth and heading south to the Caribbean to fight the Spanish. Another account has it that he was a little child when he was abducted in Bristol, turned into a ship’s servant, and shipped off to a plantation in Barbados.

August 1665 saw the first mention of Morgan in a report by Jamaica’s governor. His orders to “gather English privates and capture captives of the Spanish country, through which he may learn of the enemy’s preparations to attack Jamaica,” came from the Council of Jamaica as early as January 1668. This meant that Morgan had the backing of the government to wage war against the Spanish in the West Indies.

He conquered and plundered cities, sometimes employing particularly heinous tactics. And thus, the pirates used a human shield of abducted priests and nuns to protect themselves during the attack on one of the fortifications. Because of this, they were able to successfully breach the wall and gain entry. Locals were tortured by the British to reveal where they had hidden money and other valuables, which accompanied the plundering of the city. They also asked the natives for a ransom of 100,000 piastres.

Morgan had planned to continue on to Cartagena, but the pirates got so intoxicated at a feast he had prepared for his commanders aboard the flagship vessel Oxford that it exploded. Only Morgan and a select few others made it out alive. He regrouped with a fresh crew and kept up his robbing and murdering around the coast of Venezuela.

The captain’s tremendous bravado and skill as a strategist were praised by his contemporaries, who praised his ability to plan and execute intricate naval and terrestrial operations. Therefore, it should come as no surprise when the Council of Jamaica issued Admiral Morgan a privateer’s commission in 1670. He was given free reign to assault Spanish ships, storm forts, and conquer cities. Important information for the pirates was also included in the document: “Because the fleet receives no compensation, it will take all the commodities and merchant riches obtained in such operations and split them among themselves according to their own regulations.”

Thanks to his enhanced abilities, Morgan was able to explore previously inaccessible realms. His plan was to plunder Panama, the Spanish-owned capital of the American colonies and the wealthiest city in the Americas. All of Mexico’s gold and silver were brought here before being put on ships and transferred to the Old World.

It wasn’t until January 1671 that Panama fell to pirates after they marched for days through the jungle and assaulted the Spanish garrison from underneath the city’s defenses. The hauling of the loot required 175 mules. Some 600 people were taken prisoner with the precious treasures. The brigands on the Chagres River’s banks began dividing the booty, sparking a controversy and a conflict since the common sailors felt they had been shortchanged. Morgan and his crew didn’t hang around for these processes to wrap up; instead, they made off with most of the booty and left their old colleagues high and dry.

The Treaty of Madrid, signed in 1670, required England to suppress piracy in the New World in exchange for Spanish acknowledgment of English rule in Jamaica. Morgan’s looting voyage was a direct violation of this agreement. The British quickly denied any involvement and placed the blame on Jamaica’s governor, Sir Thomas Modiford. A warrant had him brought to London, where he was promptly thrown into the Tower. Similarly, Morgan was extradited to England, but he faced no charges there since he had been working with authorities. The governor’s innocence also couldn’t be established. After his return, he becomes Jamaica’s chief justice once more. Morgan dispatched a deputy governor and was knighted for his fidelity, foresight, and courage in 1674.

From the mid-1670s until the 1680s, Morgan played an important role in the administration of Jamaica. After being removed from this position, he spent the next several years doing whatever he pleased. He was accused of being dishonorable and having covert ties with pirates.

Edward Teach, nicknamed Blackbeard (c. 1680-1718)

Characters like Edward Teach have been the inspiration for countless fictional heroes. Primarily as a lowlife who gives off an unpleasant stench and looks vile. Captain Flint from Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island is the most well-known representation of a pirate. However, one of the characters in the novel mentions that Blackbeard is “a mere baby” compared to Flint. There have been several film and television adaptations of Teach.

Charles Johnson’s depiction of Teach’s look in A General History of the Pyrates is textbook pirate.

Captain Teach assumed the cognomen of Black-beard, from that large quantity of hair, which, like a frightful meteor, covered his whole face, and frightened America more than any comet that has appeared there a long time. This beard was black, which he suffered to grow of an extravagant length; as to breadth, it came up to his eyes; he was accustomed to twist it with ribbons, in small tails, after the manner of our ramillies wiggs, and turn them about his ears: In time of action, he wore a sling over his shoulder, with three brace of pistols, hanging in holsters like bandoliers; and stuck lighted matches under his hat, which appearing on each side of his face, his eyes naturally looking fierce and wild, made him altogether such a figure, that imagination cannot form an idea of a fury, from hell, to look more frightful.

According to contemporary accounts, the mere sight of this beard blowing in the wind broke the resolve of merchant seamen. Others describe him as “a tall, slender guy with a long black beard,” but he deliberately nurtured the impression that he was demonic. Actually, there’s a lot less information available regarding Teach.

During the War of the Spanish Succession (1701–14), Teach is thought to have begun his career as a corsair. Afterward, he joined forces with the notorious pirate Benjamin Hornigold, but soon after, he obtained his own ship, which he perfected and named “Queen Anne’s Revenge,” and began ravaging settlements along the American coast. Alternatively, it might be out of respect for the last surviving member of the Stuart family to rule England.

In May of 1718, for instance, the Queen Anne’s Revenge and a fleet of sloops raided Charleston Harbor in South Carolina, one of the greatest Atlantic ports, seized control of the ships docked there, confiscated their cargoes, and held the governor of the state prisoner until he paid a ransom. Blackbeard threatened to destroy the ships and kill the captives if they were not released. The pirates stepped ashore as discussions were going on in the city, frightening the locals. The government was forced to fork up a hefty sum of money in addition to medicine and supplies. Teach and his crew survived the summer of that year’s wreck of the Queen Anne’s Revenge by fleeing aboard other vessels (“in gratitude,” Teach landed some of the old crew on an uninhabited island).

Some time later, Teach relocated in North Carolina, shared some of his booty with the governor, and married the 16-year-old daughter of a local planter after accepting an amnesty issued by the authorities (normally an amnesty follows a fresh round of pirate trials). But the losses from Teach’s ventures were so high that the Virginia government offered a prize of 400 pounds in the fall of 1718 for the capture or death of any pirate. Blackbeard’s body had 25 saber wounds and five gunshot wounds after the last struggle for Teach on Ocracoke Island. The outlaw’s severed head was hanged from the ship’s prow. The tradition has it that he was brought to Richmond and put on a pillar of shame.

Bibliography:

- Ellms C. The Pirates Own Book Authentic Narratives of the Most Celebrated Sea Robbers, 1837.

- Richard Zacks, The Pirate Hunter: The True Story of Captain Kidd (Hyperion, 2003)

- Jamieson A. G. Lords of the Sea. A History of the Barbary Corsairs. London, 2012.

- Konstam, Angus (2011). Piracy–The Complete History from 1300 BC to the Present Day. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Lee R. E. Blackbeard the Pirate. A Reappraisal of His Life and Times. Winston-Salem, 2002.

- Zacks R. The Pirate Hunter: The True Story of Captain Kidd. New York, 2003.