Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart is the most mythologized figure in the history of music. No other biography has given rise to as many rumors, legends, detective stories, and fictions.

- Mozart Was a Child Prodigy Who Began Playing and Composing Music at the Age of Four

- Mozart Was Forced to Practice Music

- Mozart Quickly Became a Child Star and Performed All Over Europe

- Mozart Was Supported by Kings from Childhood

- Mozart Was Considered a Genius, So He Earned a Lot

- But He Was Bad with Money and Lived Very Poorly

- Mozart Stole Other People’s Ideas

- Mozart Collected Wigs

- Mozart Had Many Women

- Mozart Loved Obscene Humor and Was Not Particularly Smart

- Mozart Was Blind or Deaf

- Mozart Wrote the “Requiem” Overnight at the Request of a Mysterious Stranger, Foreseeing His Own Death

- Mozart Was Poisoned by His Archrival, Salieri

- The Poisoned Mozart Died in Poverty and Obscurity

Some rumors appeared during Mozart’s lifetime, thanks to his relatives, friends, and acquaintances. Others emerged much later, during the Romantic era at the beginning of the 19th century: the Romantics were inspired by both Mozart’s work, especially the story of Don Giovanni, and his early death. Here, we explain where the various legends about the great composer came from.

Mozart Was a Child Prodigy Who Began Playing and Composing Music at the Age of Four

Verdict: This is almost true.

Mozart was indeed a child prodigy and the most famous one in the history of music. He began playing early and mastered the art remarkably quickly. Leopold Mozart, a legendary music teacher, described his son’s remarkable achievements on the clavier, an early version of the modern piano: “Wolfgangerl learned the Minuet and Trio on January 26, 1761, at half-past nine in the evening, in half an hour, the day before he turned five.”

Meanwhile, the boy was also learning to play the violin—one of his childhood violins can be seen in Salzburg, in the house where he was born. Immediately after his son’s birth, Leopold Mozart published a textbook, “A Treatise on the Fundamental Principles of Violin Playing” (“Versuch einer gründlichen Violinschule”), which he apparently began to test. At the age of seven, Wolfgang Mozart was already playing the violin for the archbishop, and at eight, he started performing on the organ.

The earliest surviving manuscripts by Mozart date back to 1764, when the author was also eight years old. Before that, the child’s improvisations and compositions were recorded by his father. According to Leopold’s meticulous notes, Mozart completed his earliest improvisation at the age of five, in April 1761. Less than a year later, he composed his first piece—an Allegro in F major for the clavier. Among the world’s classical composers, only Sergei Prokofiev began composing at such an early age.

Mozart Was Forced to Practice Music

Verdict: False.

Leopold Mozart was a progressive and talented teacher, so he used encouragement rather than punishment. His educational approach required time, patience, and dedication, allowing him to nurture his son’s talent without harsh intervention. He never used corporal punishment on his children. To Wolfgang, his father’s authority was unquestionable—he practically worshipped him, claiming that “after the Lord comes Papa.” In turn, Leopold saw him as a genius.

Wolfgang amazed his parents so much with his talent that they tended to indulge him. Johann Adolf Hasse, one of the famous composers of the time, even worried: “Let’s just hope the father does not spoil him too much with exaggerated praise.”

Mozart Quickly Became a Child Star and Performed All Over Europe

Verdict: True.

Leopold Mozart was the father of two prodigies: Nannerl, Wolfgang’s older sister, was also a promising performer. Their first tours began in January 1762, when the younger Mozart was six years old and his sister was ten. Although Munich, where they headed, is not far from Salzburg, it was still a real tour. At the court of Maximilian III Joseph, Elector of Bavaria, they spent three weeks.

Together with his sister, Wolfgang toured all the musical capitals of Europe. Just six months after the triumph in Munich, their father took the children to Vienna. At one stop, they gave their first public concert, and in Vienna, a whole series of performances awaited them: at the court of Maria Theresa, in aristocratic salons, and in the homes of foreign ambassadors. It was then that they received an invitation to perform in Versailles.

In early summer 1763, the whole family set off on a three-year tour of Europe: Munich, Augsburg, Ulm, Ludwigsburg, Bruchsal, Mannheim, Schwetzingen, Frankfurt am Main, Koblenz, Bonn, Cologne, Aachen, Brussels, and finally, Paris and Versailles. These were just the cities where they gave concerts. The main goal of the journey was an audience with Louis XV in Versailles. The next destination was London. George III was so impressed by the performance that he wished to hear the prodigies again at celebrations for another anniversary of his ascension to the throne.

After almost a year in England, their travels continued: Canterbury, Calais, Lille, Ghent, Antwerp, The Hague, Amsterdam, Utrecht, Antwerp again, Brussels, Paris, Versailles, Dijon, Lyon, Geneva, Lausanne, Bern, Zurich, Donaueschingen, and finally, Munich and Salzburg once more. Wolfgangerl returned home as a famous musician who had performed before kings. On the eve of his fourteenth birthday, the family went to Italy. The second and third Italian journeys, undertaken in 1771 and 1772 by the male members of the Mozart family, were triumphant. Europe was conquered, and with it, the entire musical world.

Mozart Was Supported by Kings from Childhood

Verdict: True.

During his European tours, Mozart became familiar with court life, and later, the Viennese court became his place of work. The pinnacle of his court career can be considered his audience with Pope Clement XIV at the Vatican. Mozart was 14 years old, and the Pope had already inducted him into the Order of the Golden Spur.

As an adult, Mozart continued to associate with aristocrats and monarchs he had met in his childhood. Sometimes, his independent character and sharp tongue could cause trouble. A famous example is the dialogue between the composer and his main patron, Joseph II, at the premiere of The Abduction from the Seraglio (Die Entführung aus dem Serail):

ORSINI-ROSENBERG: Too many notes, Your Majesty?

Source

EMPEROR: Exactly. Very well put. Too many notes.

MOZART: I don’t understand. There are just as many notes, Majesty, as are required. Neither more nor less.

Mozart Was Considered a Genius, So He Earned a Lot

Verdict: True.

Over the years of touring, Mozart managed to earn a lot of money; his family became one of the wealthiest in the provincial Salzburg. At 18, Wolfgang already received an annual salary of 150 gulden as the concertmaster of the court chapel. But this was not his only source of wealth. Admirers, including royalty, regularly presented him with gifts. Typically, these were jewels, which the musician, following the practice of the time, pragmatically “cashed in.” Significant income also came from European productions of his operas and publications. He continued to perform as a virtuoso.

At the age of 25, Mozart finally moved to Vienna, left his service, and became a freelance artist. Orders kept coming in, and his operas and performances were successful. For four years, he held solo concerts, known as “academies,” for the most distinguished audiences, including the imperial couple. For one of these concerts, he received a fee of nearly 1,600 gulden.

Like most musicians of the time, Mozart earned not only from performances and theatrical productions but also from lessons—conducting 3–4 lessons daily. The number of students from wealthy, preferably aristocratic, families was a measure of success in the musical world.

At 30, Mozart was living in Vienna with his family and received a steady annual salary as a court chamber musician at the Viennese court. His only requirement was to provide musical arrangements for balls—a position that was more honorary than laborious. The Austrian Emperor Joseph II commissioned an opera from him, and the King of Prussia, Frederick William II, commissioned six string quartets.

Mozart was considered a fashionable composer, so people were willing to pay for his work. However, his talent was not universally recognized. His contemporaries—Antonio Salieri, Domenico Cimarosa, and Vicente Martín y Soler—received far more recognition during their lifetimes. Mozart believed he deserved more and was pleased to quote in a letter to his father the praise of a nobleman: “Such people appear only once every 100 years.”

But He Was Bad with Money and Lived Very Poorly

Verdict: Partially True.

The extreme poverty of the composer is a myth. It was created by Constanze Mozart, who sought help from her husband’s influential acquaintances after his death. The debts were paid off fairly quickly, which means they were not very large.

However, Mozart indeed was not very skilled with money, although he constantly tried to convince his father otherwise. He spent all he earned on renting expensive housing in central Vienna, maintaining servants and his own carriage, entertaining guests, clothes for himself and his beloved wife, and regular grooming to meet court standards. He got married in Vienna’s main cathedral, St. Stephen’s. In the last years of the composer’s life, Constanze frequented an expensive resort, which added to the expenses. It is difficult to say whether the treatment was a necessity or just as fashionable as the expensive clothes.

Mozart could not control not only his expenses but also his income. He clearly missed out on royalties from many theaters staging his operas. Copyright laws were poorly enforced at the time, and Mozart neither liked nor was able to chase down debtors. He loved and knew how to compose and perform music—and he spent all his time on it. In the last four years of his life, his financial situation worsened. But this was not Mozart’s fault: Austria entered a war, which led to an economic crisis. Patrons became less generous, and the composer did not live to see better times.

Mozart Stole Other People’s Ideas

Verdict: This is not true.

Originality became the main virtue of music only after Mozart’s death: the motto of the Romantic era was the idea of inventing musical material. In Mozart’s time, the concept of one’s own and others’ ideas, or plagiarism, had not yet been formed. Creativity was based on working with models—these could be a genre, style, or even a musical theme composed by someone else. This is why the historical style of that era is now more recognizable than the individual styles of specific authors.

Mozart worked with a vast amount of what he heard and played; borrowing for him was a dialogue with other composers and other compositions. Today, we do not always catch the wit of this dialogue. Many authors important to Mozart have been forgotten, and his music has become a symbol that sums up the entire era.

Mozart Collected Wigs

Verdict: This is more likely not true.

At that time, wigs were an integral part of the appearance of a secular person, although Mozart himself wore them only on special occasions and was often depicted in portraits with his own well-styled hair. He mentions the burdensome expenses on barbers only in passing in some letters. There are also recollections from friends about his dandyism and detailed descriptions of fashionable clothing in his letters. However, nothing is known about Mozart’s passion for collecting wigs.

Mozart Had Many Women

Verdict: This is more likely not true.

We cannot judge this accurately because the only sources of information are Mozart’s letters—mainly to his father. 27-year-old Wolfgang Amadeus wrote to Leopold:

I can in no way live like most young men today. Firstly, I am too devoted to religion; secondly, I have too much love for my neighbor to seduce an innocent girl; and thirdly, I feel too much horror and disgust, fear and dread of diseases, and too much love for my health to get involved with promiscuous women. And I can swear that, up to now, I have not had dealings of this kind with any woman—because if it had happened, I would not have hidden it from you…

However, it is possible that Mozart was not entirely honest with his father, knowing his strict religious and moral principles. Before leaving Salzburg, he was under close parental supervision, and, breaking free from this care, he immediately fell in love.

Judging by Mozart’s letters, the singer Aloysia Weber, whom he planned to marry, hoped to use him to obtain lucrative contracts in Italy. Wanting to help his beloved’s career, Mozart wrote several pieces for her. After joining an opera troupe, Aloysia lost interest in him, and then Wolfgang’s cousin, Maria Anna Thekla, became his comforter. The nature of their relationship and the degree of intimacy are not entirely clear, but the “Letters to the Little Cousin” became scandalously famous in Mozart’s studies due to their obscenities, which do not go beyond toilet humor.

Constanze, who became the composer’s wife, was Aloysia’s sister and also a singer. Mozart’s biographers are mostly indifferent to Constanze’s story because, unlike her sister, she did not achieve artistic success and did not influence her husband’s work in any way. Apparently, Mozart was happy in this marriage, despite various distressing circumstances, primarily the death of four children.

Mozart Loved Obscene Humor and Was Not Particularly Smart

Verdict: The first is true, the second is not.

Mozart resorted to toilet humor even in letters, and these letters have reached us due to the carelessness of the addressees. Communicating with his cousin, Mozart did not shy away from expressions:

And now I have the honor to ask how you are feeling, how is your health? Are your bowels in order? Is your skin smooth?—Tell me, have you not gotten tired of me yet? Do you often use chalk when writing? Do you remember me from time to time? Do you ever want to hang yourself? Were you ever mad at me? At poor fool? Would you like to make peace voluntarily, or else I could let out a loud one? Well, now you’re laughing to tears—victory!—Let our behinds become a symbol of peace! I knew you wouldn’t resist for long. Yes-yes, I always believe in my victory, and even if I have a bowel movement after lunch, I will still leave for Paris in two weeks. And if you want to reply to me, write from Augsburg right now, and write quickly so I can get the letter. If I’ve already left, then while waiting for a letter, I will receive only crap.

Commentators on these letters have repeatedly noted that this kind of correspondence was commonplace for the residents of Salzburg in that era. Mozart’s parents also corresponded in a similar style.

Mozart was far from stupid and was very well-educated. He spoke at least three European languages, wrote operas in Italian and German, knew Latin, and composed spiritual works in it. Throughout his life, he communicated with the most educated and intelligent people of his time. He demonstrated knowledge and intelligence in his art and in his reflections on music and its laws, which have come down to us thanks to his letters.

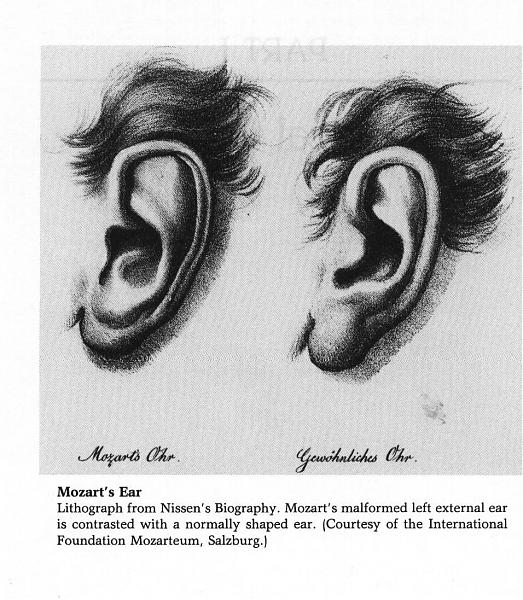

Mozart Was Blind or Deaf

Verdict: False.

He is often confused with George Frideric Handel, who lost his eyesight, and Ludwig van Beethoven, who went deaf.

Mozart Wrote the “Requiem” Overnight at the Request of a Mysterious Stranger, Foreseeing His Own Death

Verdict: This is partly true.

There was indeed a mysterious stranger’s request for the “Requiem.” However, the identity of the commissioner was later revealed, and there was no mystique to his intentions. It was Franz von Walsegg zu Stuppach, an amateur composer, who commissioned the “Requiem” for his deceased wife, intending to pass it off as his own work. This explains the mysterious circumstances surrounding the commission—he did not want to reveal his name.

Moreover, the “Requiem” was not written overnight (that feat belongs to the overture of “Don Giovanni”), and it was not even finished despite having ample time—the commissioner did not rush the composer, who was occupied with other urgent matters. After Mozart’s death, the work was completed by his pupil, Franz Xaver Süssmayr, according to Mozart’s notes. Süssmayr independently wrote the last three parts of the “Requiem.” As for the famous “Lacrimosa,” only the first eight bars were composed by Mozart—this is perhaps the most well-known musical theme he ever created.

Mozart Was Poisoned by His Archrival, Salieri

Verdict: This is unproven.

Investigations into this case continue to multiply—sometimes scientific, but more often dubious. The rumors began immediately after Mozart’s death, not without the involvement of his widow, who claimed that the deceased composer himself had suspected something. This version was also discussed among the musicians of Vienna, with Salieri’s name even being mentioned, leading him to swear to his close friends that he had nothing to do with it.

Salieri had no reason to be jealous: his position at court was much more secure than Mozart’s; he held a higher rank, and the success of his compositions had long been established. No signs of conflict or intrigue against Mozart were ever observed. On the contrary, Salieri had a reputation as a respectable man and an exceptional teacher—three geniuses, Beethoven, Schubert, and Liszt, all attended his school, and he never attempted to poison any of them. As for Mozart, he most likely died of a sudden kidney disease.

The Poisoned Mozart Died in Poverty and Obscurity

Verdict: False.

This myth arose because Mozart was buried in a common grave, but this was unrelated to his financial status. According to an edict by Emperor Joseph II, burials in individual graves were a privilege reserved only for the noblest families. All others were buried five or six at a time, without coffins. Relatives were forbidden to accompany the deceased to the cemetery or to erect monuments and crosses on the graves. These were the emperor’s ideas of economy. The edict was later repealed, but by then, Mozart’s grave had already been lost. His music, however, remains.