300 Spartans Saved Greece

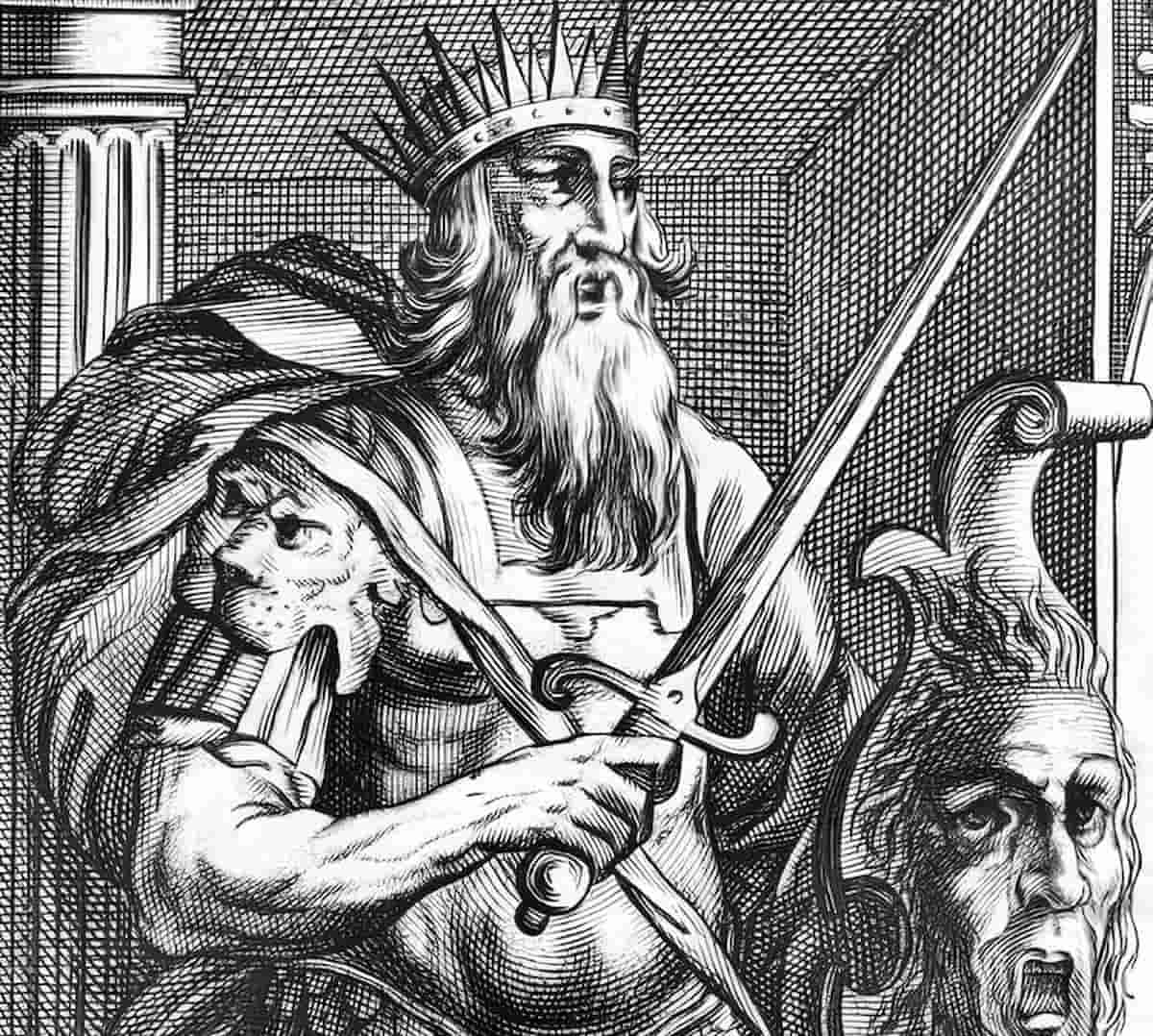

Perhaps the most famous battle in ancient Greek history is the Battle of Thermopylae, which took place in 480 BCE. During this battle, Spartan King Leonidas and his 300 warriors heroically resisted the attacks of a vast Persian army led by Xerxes, thereby saving Greece from destruction and enslavement. “300 Spartans” and “Thermopylae” have symbolized heroic resistance against overwhelming enemy forces for several centuries. This narrative was most recently dramatized in the blockbuster film “300” by Zack Snyder (2007).

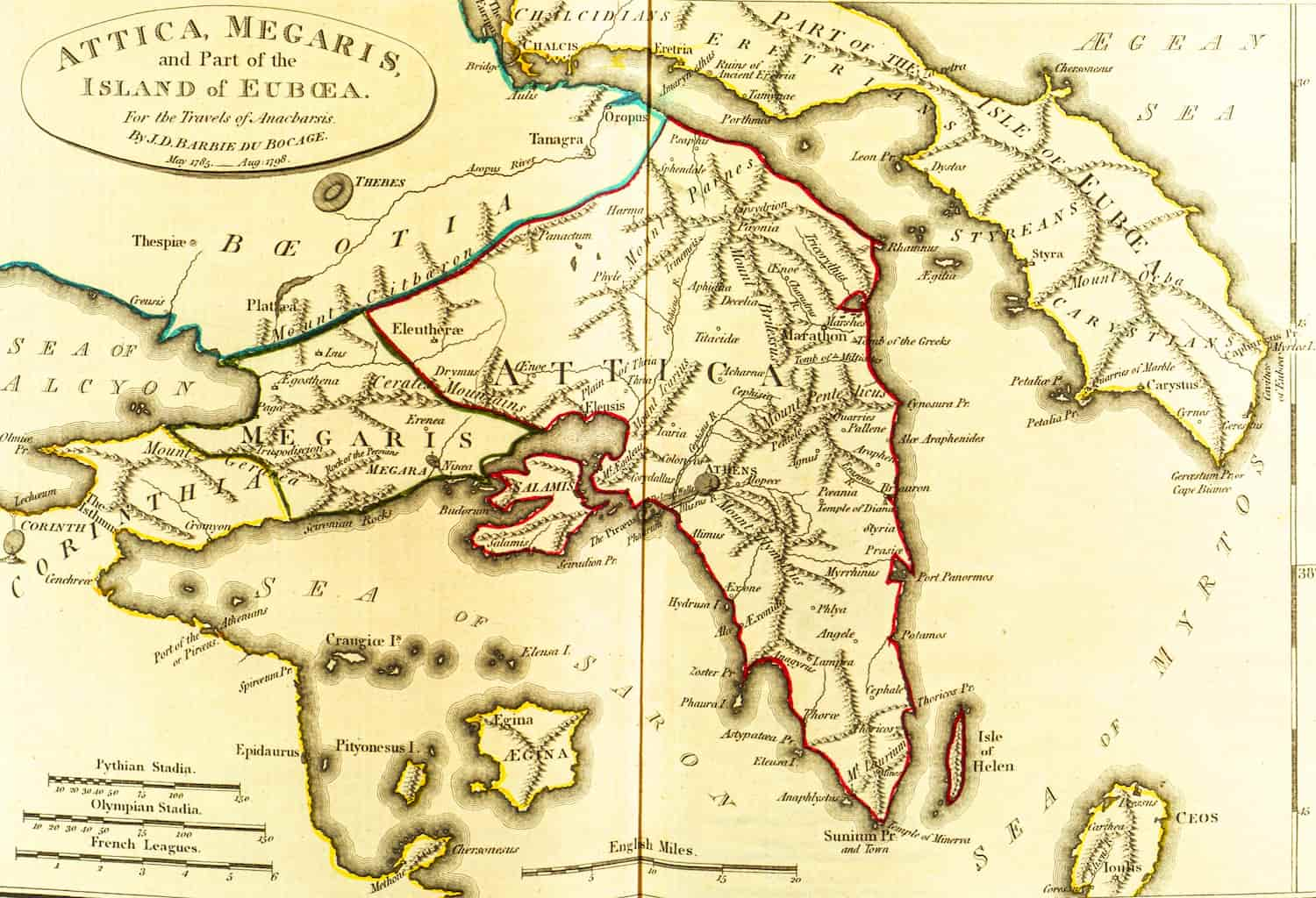

However, both Herodotus and another ancient Greek historian, Ephorus of Cyme, whose accounts form the primary sources of information about this battle (Ephorus’s version was preserved in a retelling by Diodorus Siculus), described the event somewhat differently. Firstly, the battle was lost—the Greeks only managed to delay Xerxes briefly. In 480 BCE, the Persian king and his allies conquered most of Hellas, and only a month later, in September 480 BCE, the Greeks defeated them at the Battle of Salamis (at sea) and a year later at the Battle of Plataea (on land).

Secondly, the defenders were not only Spartans—various Greek city-states, including Mantinea, Arcadia, Corinth, Thespiae, and Phocis, also sent troops to the pass, resulting in an initial force of 5,000 to 7,000 warriors who resisted the enemy’s first assault. Even after Ephialtes, a citizen of the Thessalian city of Trachis, showed the Persians a way to encircle the Greeks, and Leonidas dismissed most of the warriors to spare them from inevitable death, the remaining force still numbered around a thousand.

Hoplites from the Boeotian city-states of Thebes and Thespiae chose to stay, as the Persian army was bound to pass through Boeotia (the Peloponnesians—Mantineans, Arcadians, and others—hoped that Xerxes would not reach their peninsula). However, it is possible that the Boeotians acted not out of rational considerations but chose to die a heroic death, just like Leonidas’s warriors.

So why has the legend only remembered the 300 Spartans, even though ancient historians documented all the members of the Greek army? Perhaps it is because people tend to focus on the main characters and forget the secondary ones. However, modern Greeks have decided to rectify this: in 1997, near the monument to the Spartans (a bronze statue of Leonidas), they erected a monument in honor of the 700 Thespians.

The Library of Alexandria Was Burned by Barbarians

The Library of Alexandria was one of the largest libraries in human history, housing between 50,000 and 700,000 volumes. It was founded by the rulers of Egypt during the Hellenistic period in the 3rd century BCE. It is often believed that the library—a symbol of ancient scholarship—was completely destroyed by barbarians who hated classical culture. This idea is depicted, for example, in the 2009 film “Agora,” directed by Alejandro Amenábar and dedicated to the fate of the Alexandrian scholar Hypatia.

In reality, barbarians were not responsible for the library’s demise, nor did it vanish due to a fire. Some sources (such as Plutarch in “Life of Caesar”) do mention that books were damaged by fire during Caesar’s siege of the city in 48 BCE—but modern historians tend to believe that it was not books but papyrus scrolls near the port (containing accounting records of goods) that were burned.

The library may have also been damaged during Emperor Aurelian’s conflict with Zenobia, the queen of Palmyra, who seized Egypt from 269 to 274 CE. However, there is no direct evidence of any grand fire that completely destroyed the library.

Most likely, the Library of Alexandria disappeared due to budget cuts that continued over several centuries. Initially, the Ptolemaic dynasty (which ruled Egypt during the Hellenistic period) ensured significant privileges for the library’s staff and provided the necessary funds for acquiring and copying tens of thousands of scrolls. These privileges were maintained even after the Roman conquest.

However, in the “crisis” of the 3rd century CE, Emperor Caracalla abolished stipends for scholars and forbade foreigners from working in the library—turning many of the books into a dead weight, unreadable, and uninteresting to anyone. Gradually, the library simply ceased to exist—its books were either destroyed or deteriorated naturally.

Modern Democracy Was Invented in Athens

The system of governance that existed in Athens from around 500 to 321 BCE is considered the world’s first democratic system and is seen as a precursor to the modern political structures of Western countries. However, Athenian democracy had little in common with modern democracy. It was not representative (where citizens’ political decision-making is carried out through elected representatives) but direct: all citizens were required to regularly participate in the work of the Assembly—the highest governing body.

Additionally, Athens was far from the ideal of full political participation by the entire “people.” Slaves, metics (foreigners and freed slaves), and women, who made up the majority of the population, had no citizen rights and could not participate in state governance. By some estimates, there were three times as many slaves as free citizens in democratic-era Athens.

In practice, even poor citizens were often excluded from the political process; they could not afford to spend an entire day at Assembly meetings (though there were periods when Athenian citizens were paid for their attendance).

The word “democracy” (like many other concepts) acquired a new meaning in the late 18th century when the idea of representative democracy emerged in France (the people exercise their power through elected representatives). At the same time, there was a struggle to expand voting rights, and today, most restrictions on voting rights are considered anti-democratic.

Amazon Women Did Not Exist

Among the Greeks, there were widespread legends about the Amazons—a warrior people consisting solely of women who wielded bows and even cut off one breast to handle the bow more easily. The Amazons met with men from neighboring tribes only for the purpose of conceiving children; boys were either returned or killed.

Historically, scholars considered the Amazons to be fictional beings—especially since Greek authors placed them in various distant regions of the inhabited world (Scythia, Anatolia, or Libya). This categorization put them on par with the monsters and exotic creatures of distant lands that, for various reasons, differed from “normal” society.

However, while excavating Scythian burial mounds in the steppes of the Black Sea region, archaeologists discovered the graves of female warriors, buried with bows and arrows. Most likely, women who shot bows and rode horses alongside men didn’t fit into the Greek worldview, prompting them to categorize these women as separate people.

Scythian women indeed could defend themselves—it was necessary when men migrated over long distances—and they may have initiated battles by shooting at opponents from a safe distance. However, they were unlikely to kill their sons, avoid men, or cut off their breasts—military historians are confident that this is entirely unnecessary for accurate archery.

Ancient Art is White Stone

We imagine the Parthenon and ancient statues as white. This is how they have been preserved to this day because they were made of white marble.

However, the actual statues and public buildings were originally colored; the paint simply peeled off over time. The pigments used in these paints were mineral-based (vermilion, red ochre, copper azure, copper green, yellow ochre, etc.), while the binder that “glued” the paint to the surface was organic. Organic materials decompose over time due to bacteria, causing the paint to flake off easily.

The original appearance of ancient statues could be seen at the traveling exhibition “Gods In Color: Painted Sculpture in Classical Antiquity,” organized by American and German scholars in 2007. In addition to revealing that the statues were colorful, it was also found that many of them had bronze inserts and their eyes featured convex pupils made of black stone.

Spartans Threw Children into a Chasm

One of the most famous tales about Sparta states that when a boy was born into a Spartan family, he would be taken to the edge of the Apothetai chasm (on the slopes of Mount Taygetus). There, the elders would carefully examine him, and if the boy was sickly or weak, he would be thrown into the chasm. We know this story from Plutarch’s “Life of Lycurgus,” and it remains vivid and popular today, as evidenced in the 2008 parody film “Meet the Spartans.”

Recently, Greek archaeologists have proven this story to be a myth. They analyzed the bones extracted from the Apothetai gorge and found that the remains belonged only to adults—specifically, forty-six men aged 18 to 55 years. This finding aligns with other ancient sources, which state that the Spartans threw traitors, prisoners, and criminals into the chasm, not children.

Pandora’s Box

The myth of Pandora’s box is known to us from Hesiod’s retelling in his poem “Works and Days.” In Greek mythology, Pandora is the first woman on Earth, molded from clay by Hephaestus to bring misfortune to mankind. He did this at Zeus’ request—Zeus wanted to punish humanity through Pandora’s actions for Prometheus stealing fire from the gods for them.

Pandora became the wife of Prometheus’ younger brother. One day, she discovered something in their house that was forbidden to open. Driven by curiosity, Pandora opened it, releasing numerous misfortunes and calamities into the world. In horror, she tried to close the dangerous container, but it was too late—the evils had already spread across the world; only hope remained at the bottom, thus depriving people of it.

In Russian, the term “Pandora’s box” has become a common expression referring to someone who has done something irreparable with massive negative consequences: “He opened Pandora’s box.”

However, in Hesiod’s account, it is not a box or casket but a pithos—a large storage jar that could be as tall as a person. Unlike the “clay” Pandora, the container of evils was made of sturdy metal—Hesiod describes it as indestructible.

Where, then, did the “box” come from? It is likely due to the humanist Erasmus of Rotterdam, who translated Hesiod into Latin in the 16th century. He mistook “pithos” for “pyxis” (Greek for “box”), perhaps recalling at the wrong time the myth of Psyche, who brought back a box of incense from the underworld. This mistranslation was later solidified by famous 18th–19th century artists (such as Dante Gabriel Rossetti), who depicted Pandora with a box.