The Nemes is the most iconic headdress of the pharaohs, worn from the Old Kingdom to the Ptolemaic period. It is well-known to the public through numerous representations, notably the golden funerary mask of Pharaoh Tutankhamun or the head of the Sphinx on the Giza Plateau. Klaft was a traditional, loose-hanging headscarf that was worn as protection from the sun. This headdress evolved into Nemes, a striped, ceremonial variant reserved for kings, pharaohs, and deities. Nemes was often adorned with an Uraeus serpent on his forehead, an ancient Egyptian symbol of divine protection and kingship.

Description

The Nemes is a linen headpiece with blue and yellow stripes (for example, Horemheb) or red and white (Tutankhamun), quite intricate, composed of several parts that evolved over time; this allows for an approximate dating of the patron of the artwork depicting it.

The different parts are:

- the Khat headdress: the main part covering the top and back of the head, from the forehead (upper edge) to the nape (which leads to the braid);

- the temporal parts: lateral parts covering the temples and forming the fold between the headdress and the wings;

- the frontal band: a golden band holding the headdress by encircling the temporal parts and resting on the ears; it allows for the headdress to be held on the sovereign’s head;

- the uraeus: representation of the cobra god supposed to protect the sovereign against his enemies;

- the wings: parts framing the sides of the king’s face, starting from the headdress and flaring out to the shoulder to form a sort of triangle;

- the droops: parts extending the wings, folding down on the king’s chest and tapering;

- the braid: part that finishes the back of the headdress, in the form of a braid going from the nape to the middle of the back.

The stripes, symbolizing the sun’s rays, likely highlight its solar aspect. Given the assimilation to the sun, the Nemes is linked to the solar cycle and rebirth; thus, the king can wear this crown in a funerary context. Before the appearance of the khépresh in the New Kingdom, the Nemes was the coronation crown symbolizing a new king; this association with coronation links the Nemes with the god Horus as the “living king.”

Symbolism

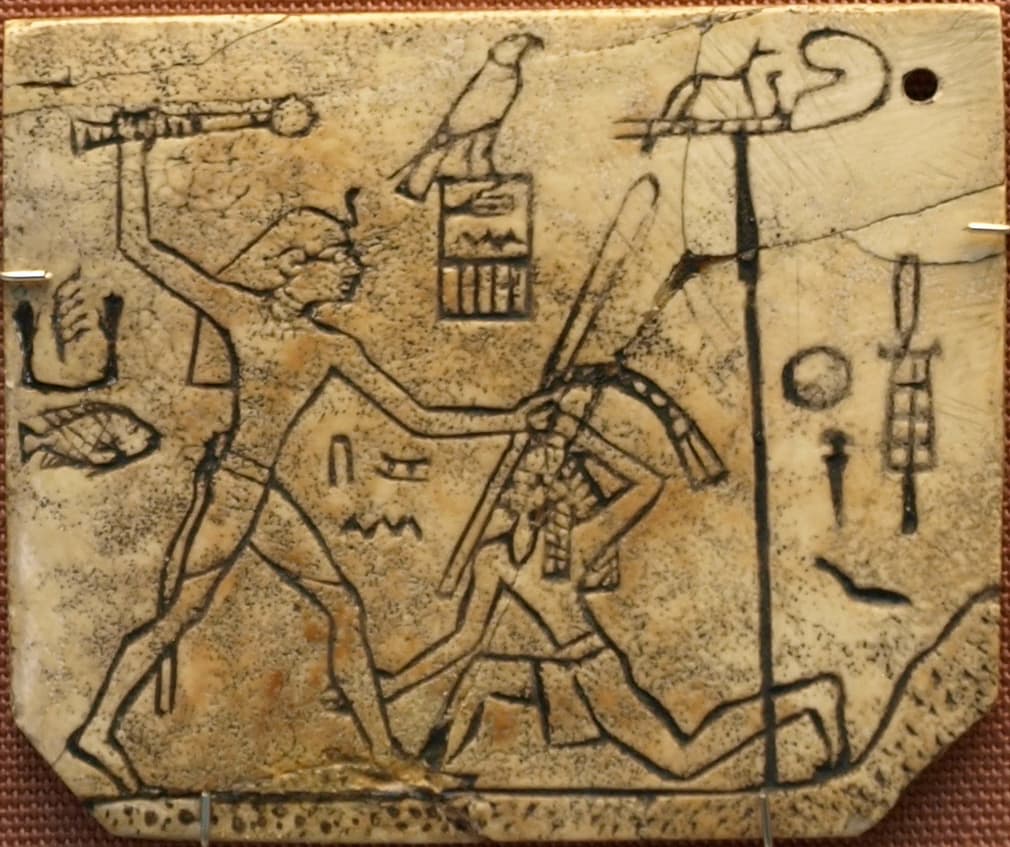

The earliest depiction of the Nemes with the uraeus that has reached us is the plaque of Pharaoh Djer (1st Dynasty) made of ivory, preserved in the British Museum. The first known sculpture of the Nemes depicts Pharaoh Djoser. Among the latest are statues of Roman emperors, including Augustus. The Nemes are also present on the head of the Great Sphinx.

The Nemes is one of the attributes shared by the pharaoh of Egypt and the deities, distinguishing him from ordinary mortals.

Contrary to popular belief, the king was indeed the only one allowed to wear this headdress, a symbol of his office. The pyramid texts designate the Nemes as the symbol of the vulture goddess Nekhbet.

The panels framing the king’s face represent the protective wings of the goddess.

Design and Features

Nemes was the royal headgear in ancient Egypt and one of the symbols of power for the Egyptian pharaohs. It was a cloth made from fabric, usually striped (in most depictions, blue with gold), woven into a knot at the back and with two long side pleats, cut semi-circularly and descending onto the shoulders.

The Nemes served as protection from dust and sunburn and were a privilege of the royal family. The Nemes covered the entire upper and back parts of the head, leaving the ears uncovered. The crosswise side of the Nemes fabric was laid horizontally on the forehead, secured with a ribbon, and on top of it, the uraeus—the image of the cobra goddess Wadjet—was worn. In some cases, the double crown of Upper and Lower Egypt (pschent) could be worn over the Nemes, as evidenced, among other things, by the colossi of Ramesses II at Abu Simbel.

Sometimes the word “Nemes” refers only to the royal striped scarf; therefore, it is considered a variety of the khepresh, as any Egyptian scarf tightly fitting the head is called. The khepresh was widespread among representatives of all social classes. Among ordinary Egyptians, the khepresh could be white or striped, and the color of the stripes depended on the status and occupation of the owner; for example, soldiers had red stripes, priests had yellow ones, and so on. Only the pharaoh could wear a scarf with blue longitudinal stripes.

History

The Nemes consisted of a triangular piece of cloth made of linen. It was laid tightly over the forehead, fastened at the temples, and tied at the back like a bonnet or a hood. The Nemes then hung in folds over the head, down the neck, and sides, leaving only the face and possibly the ears exposed.

Simple Nemes were cut straight across at the bottom, while ceremonial variants could be tied together in a pointed “lion’s tail” at the back, at the top of the back. The Nemes then had two flaps or end pieces that fell down towards the chest on each side of the neck. The shape of the Nemes resembled the long, full, bell-shaped wigs worn over shaved heads and were common for both genders in ancient Egypt.

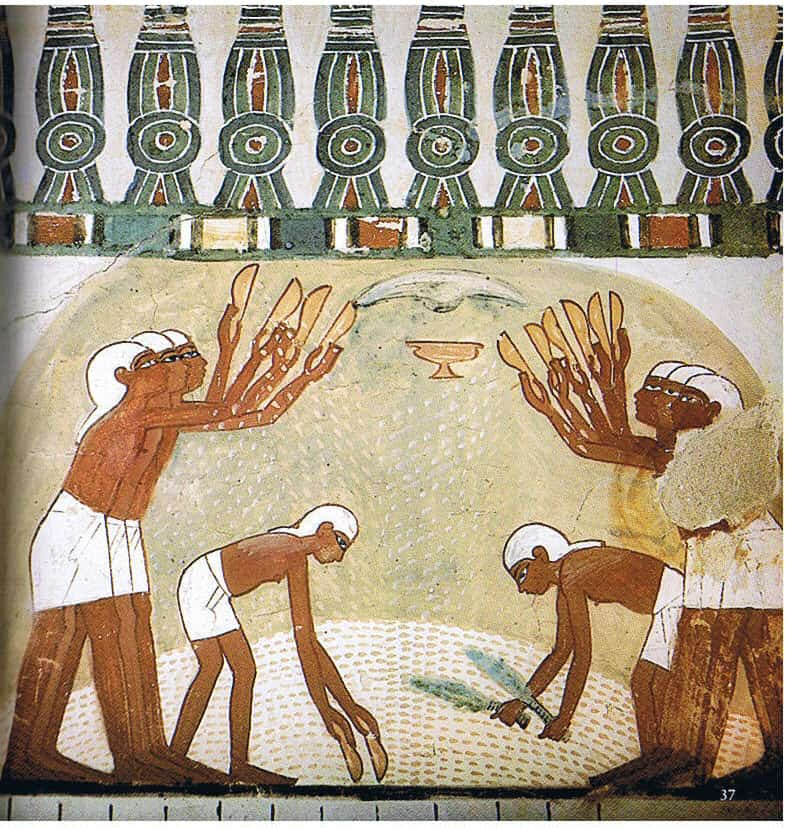

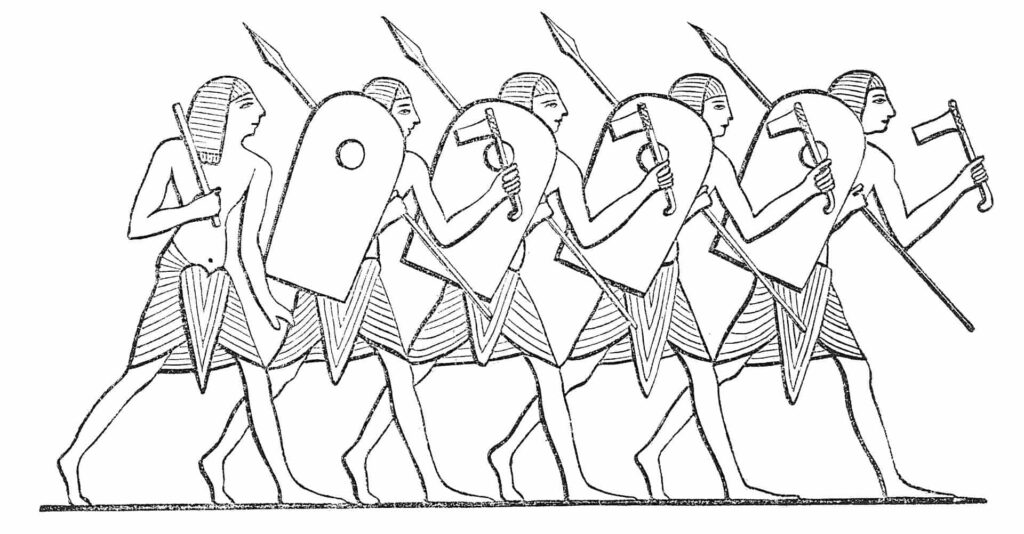

Nemes were particularly used by men, often from higher social classes, as slaves and farmers were often sparsely dressed or completely naked. It also appears that soldiers during the 19th Egyptian dynasty, unlike those during the 18th, wore striped headscarves.

Royal Headgear

The first pharaoh known to be depicted with a Nemes is Djoser, who reigned from around 2690 to 2670 BC. He was also the one who built the first pyramid, the Step Pyramid at Saqqara. Although Egyptian ancient history spans millennia, the basic features of clothing changed little.

This is due in particular to the Egyptians’ respect for tradition and reluctance to change.

Also, the ancient Egypt’s other female ruler, Sobeknefru (ca.1787-1783 BC), was portrayed with a royal nemes and shendyt, a loincloth or kilt, over a women’s garment. The same occurred three hundred years later when one of Egypt’s most famous pharaohs, Hatshepsut, who ruled around 1473-1458 BC, again adopted traditional male regalia, including the Nemes with uraeus, false beard, and loincloth. She likely did not deny her own gender, but probably wanted to show authority to foreign rulers, respect traditions, and be accepted by the country’s population.

Several pharaohs are depicted with a Nemes and double crown, a symbol of unified Upper and Lower Egypt. In ancient Egyptian images and statues, sphinxes with human heads, such as the Sphinx at Giza, are often seen wearing headscarves. Even then, they are equipped with the divine uraeus snake.